This navy yard had grown almost exponentially over the previous decade in size and in complexity. In February 1941, the New York Navy Yard marked its 140th anniversary. It also marked the end of Admiral Woodward's term as commandant. In a statement for the occasion Woodward noted that when he assumed command he had found no history of the navy yard. In response he asked James West, the chief civilian administrator of the yard, to write one. He was now proud to announce that West had finished the book in time for the celebration. Using the Yard's files West had been able to trace the narrative of the navy yard from colonial days when it was just a swamp up through its still-expanding present-day growth. On retiring two weeks later, Woodward hailed the New York Navy Yard as "unsurpassed in efficiency," and claimed his years as commandant the best assignment of his career. By then the navy yard then had more than 20,000 workers and a annual payroll over $40 million. A few months earlier, the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce estimated that of the Yard's production value of $388 million, some $250 million passed directly to the borough in terms of goods and services bought and wages paid. [James H. West, "A Short History of the New York Navy Yard," typescript manuscript, New York Navy Yard, 1941. In some catalogs, Admiral Woodward, who added a foreword, is listed as author. NYT, 16 February 1941; BE, 1 March 1941. NYT, 16 November 1940. Reminder: The Navy never referred to the place as the Brooklyn Navy Yard, but instead by its official title, the U.S. Navy Yard, New York, or in day-to-day terms, as the New York Navy Yard.]

In the fall of 1941 someone at the Brooklyn Navy Yard drew up an information sheet that showed its accomplishments of the previous two years. On 1 October 1939, the Yard employed 9195 people, at a daily wage of $66,079. As of 1 October 1941, 22,658 people worked at the navy yard, a jump of 246 percent, receiving $160,244 in wages daily. Including the 3600 then working for contractors and the 1000 WPA employees, the BNY supplied jobs to 27,258 civilians. Of those directly on the Yard's payroll, 18,750 worked days, 2427 worked evenings, and 1481 labored on the graveyard shift. An average of 1111 people inquired for jobs each day at the Labor Board and the Board had accumulated some quarter-million cards of those wanting to be notified of future exams. In the first nine months of 1941 the Board certified 19,195 workers, which does not include the IVbs, of whom 11,822 showed up to start work. (As the official rolls increase by 4781 for Grades I-III in this period, this means that at least 2½ people were taken on for every one who succeeded in staying. As the report lists about 100 each month being discharged for failure to qualify, that would mean that about 682 per month quit on their own accord. This turnover must have made the effort to achieve a larger, trained work force even harder to accomplish.) Even with this turnout, the Yard still had 1296 openings unfilled as of 24 October, electric welders and shipfitters being in particular short supply. To accomplish its work the navy yard through its various training programs was providing vocational education over ¼ of its workforce. And as usual, Representatives and Senators Congressmen still acted as patrons for their constituents and sent in an average of twenty-four letters per day inquiring about openings or pushing individual candidates.

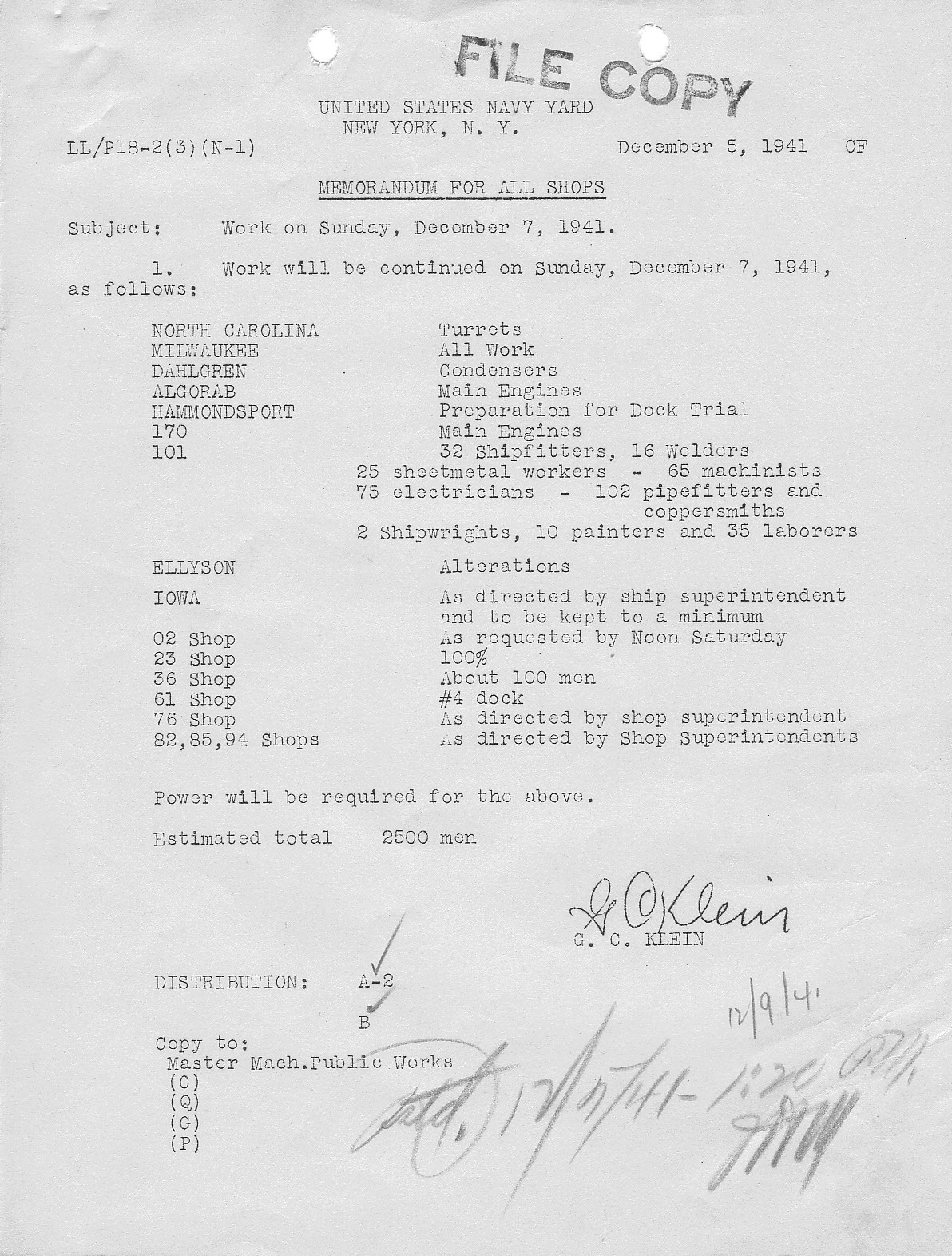

The anonymous author noted that in order to build its new, huge capital ships the navy yard had recently expanded from 198 acres to 282. It had demolished two piers and the causeway out to the ordnance island and had condemned and purchased the adjacent Wallabout Market. On the site, two new 1100-foot construction drydocks and auxiliary structures were now under construction. Presently, the Iowa was about one-third complete and had 3940 workers assigned to it; its projected launch date was 1 December 1942 (it would be launched in August 1942). Another 1130 were busy on the Missouri, 10 percent complete; its expected launch date was 1 December 1943 (it went down the ways two months after that date). At one point, 5500 people had worked on the North Carolina, which had joined the fleet six months before; it was powerful enough to supply electricity for a city of 40,000. And to show that the navy yard built other than these giants, the author noted that the Boat Shop, which built all the Third Naval District's wood craft, had turned out on average one per day since January.

Wallabout Bay was clogged; 3068 ships of all sizes entered or left the Yard in September 1941, and twenty-five railroad cars, 500 tons of stores, and 200 trucks came into the Yard each day. The Yard received $22 million worth of stores in September and shipped $14 million out, supplying among other places, the majority of material to the submarine base in New London, the training station in Newport, and the naval stations in the Caribbean. This compact, miniature town had its own post office, police force, fire equipment, salt and fresh water hydrants, ambulances, sewers, railroad, power plant and lines, schools, cafeterias, and homes. [MS, n.a., "Brooklyn Navy Yard," 23 October 1941; RG181; NA-NY.]

But it was not all a

rosy

picture. All in all, it was a stressful time for the Yard and its

workers. New construction and repair work was pouring in but the

establishment had proven itself incapable of dealing with it using

established,

peacetime procedures. New means had to be implemented to bring on

more, inexperienced workers and old trade job descriptions had to be

diluted.

A newly hired worker, after some training, would be paid the same as an

older worker even though his overall trade knowledge might be highly

limited.

Management had to expand too and learn to deal with large numbers of

workers

who a few years earlier would never have made it past the Labor Board's

front door. And while these pre-war years offered new

opportunities

correspondingly to those people as well as lay the groundwork to

provide

navy yard jobs to whole new groups of people who previously could not

have

held them for any reason, the work environment was tempered by a new

abridgement

of people's civil rights. For all intents and purposes, by the

summer

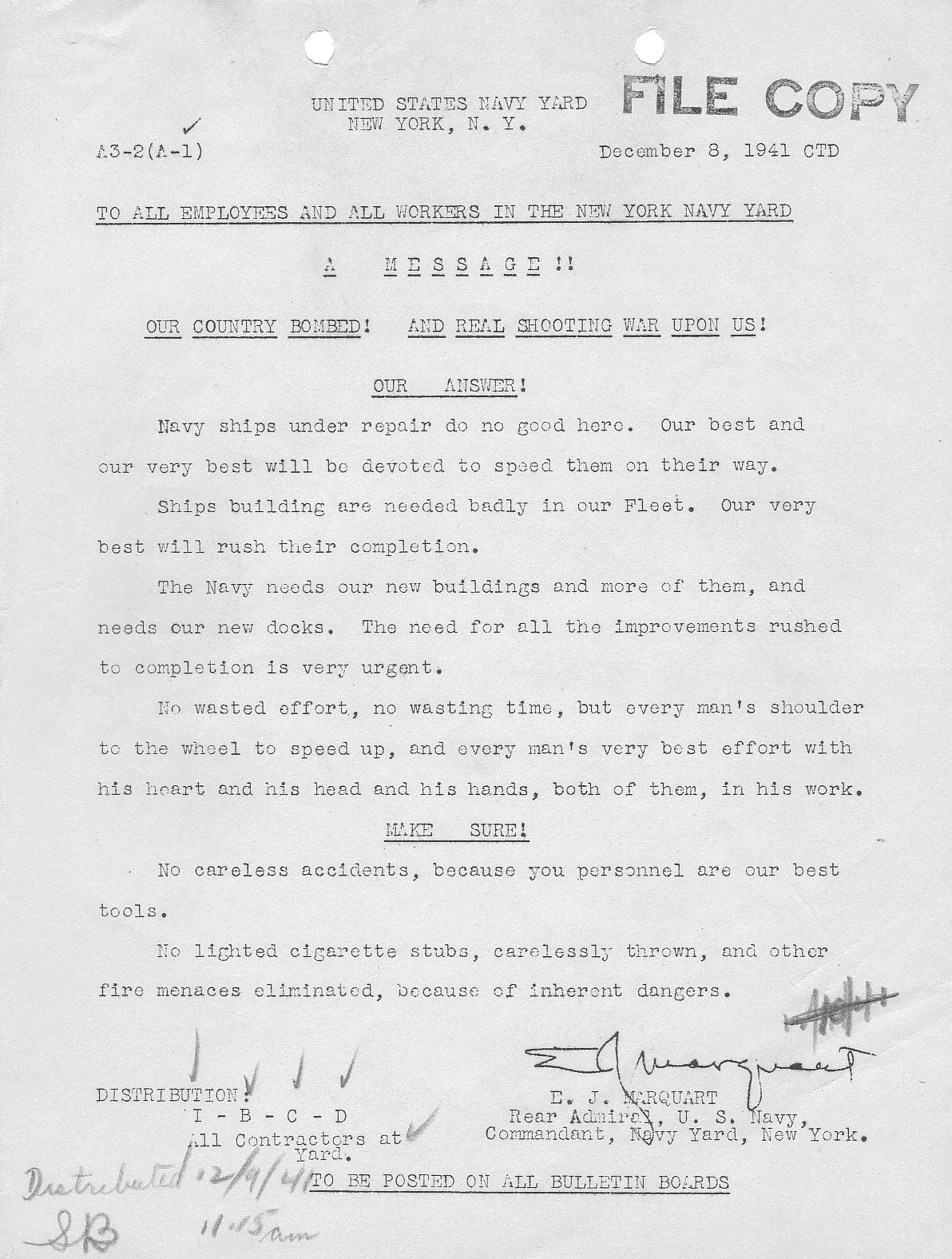

of 1941 the Brooklyn Navy Yard was already on a war footing. When

the world war came to America New York's navy yard was ready for

it.

All the foundations of the war yard had already been laid. The

war

would build upon them.

Top

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A

Postcript: The Brooklyn Navy Yard, 1942-1966

As great as the growth

in

the size of the Brooklyn Navy Yard's workforce was in the years

preceding

the U.S. entry into World War II, its increase was simply spectacular

over

the next eighteen months. From 25,920 on 31 December 1941, it

more

than doubled by the end of the following year, to 58,062. The

force

peaked at 68,800 on 30 June 1943, then remained in the mid- to

upper-60,000s

through 31 May 1945, after which it dropped to below 60,000 for the

first

time in 21/2 years, to

56,034,

by 30 September and further fell to 48,705 at year's end, 1945.

This

war-time force marked the end of a cycle of employment in the navy

yard.

In the early years of the Depression the BNY laid off workers, then

through

the Roosevelt years it had steadily increased its force until by 1939

it

lacked help, in response to which it reorganized its production methods

to make it easier for non-skilled employees to obtain a job.

During

the war itself, according to the report of one highly-placed naval

engineering

officer, the navy yard actually hoarded labor, and operated with an

excess

of about 10,000 people. [Navy Department.

Office of

Industrial Relation. Personnel Studies and Statistics Branch, “Civilian

Personnel of Naval Shore Establishments: A Summary Report, 30 June 1938

- 31 December 1945” (Washington, 1946). On the excess labor, see

Harold G. Bowen, Ships, Machinery, and Mossbacks: The Autobiography

of a Naval Engineer (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

In addition to the desire to keep on enough labor for its own sake,

this

was due in part to vagaries of operating in wartime when the BNY, a

huge

repair plant as well as construction yard, did not necessarily

know--especially

with radio silence in place--from week to week what its workforce needs

might be. Hence the stories of workers playing cards in the

wartime

Yard.]

During the war the navy yard gained its renown for its construction of large warships. It finished off the Iowa and Missouri, both started before the war, in February 1943 and June 1944 respectively. During the war years itself, while the Yard chipped in on a number of smaller, auxiliary ships, such as eight LSTs, and continued to fit-out vessels mostly built elsewhere, it turned its primary construction energy solely to aircraft carriers. It managed to send two off to the war, the Bennington and the Bon Homme Richard, and was left with three others, the Franklin D. Roosevelt, Kearsarge, and Oriskany, still in the Yard at the time of the signing of the surrender in Tokyo Bay aboard the Missouri, in September 1945. (U.S. involvement in the war both began [the Arizona] and ended with ships built at the BNY.) It was not all construction, though. Repair work consumed a considerable percentage of the Yard's work-hours. During the war, the navy yard repaired some 5000 vessels and converted 250 to war-time use, as well as served as a base for repairs to British and French vessels. The navy yard also built a seventh drydock, also of 1100 feet in length, at Bayonne, which gave the Navy extra repair space as well as provide it with an open port free of narrow channels and low-lying bridges. [For the ships built, click here. “World War II Repair Activities,” in New York Naval Shipyard “Souvenir Journal, Sesqui-Centennial Anniversary,” 1951. This document is unpaginated and contains several page-length summaries of different eras of the Yard's history. U.S. Bureau of Ships. “A Record of Progressive Achievement in Shipbuilding Since 1801,” Bureau of Ships Journal (April 1954). On the Bayonne annex, see: Bureau of Yards and Docks, Building the Navy’s Bases in World War II: History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps, 1940-1946, vol. 1 (Washington: GPO, 1947). New York Times, 28 January 1941; 31 January 1941.]

While the Brooklyn Navy Yard continued to develop along the lines we have already seen during the war, other elements obviously intervened. For instance, the Yard's need to find and train a workforce, trade, clerical, and management, triple the immediate peace-time size proved a never-ending burden throughout the war. Then, the war introduced a number of new factors into the working lives of its employees, all of which were glued together by appeals to workers' patriotism. First, the willingness to acquire and keep a navy yard job was a New Yorker's duty if not otherwise gainfully employed in the war effort, as was his or hers willingness to cooperate with management by making suggestions about production and participating in labor/management committees. One's attitude to work was important: were you willing to “speed-up,” work secular and religious holidays and over-time, maintain a positive approach to your job and perform it competently and safely? Would you consistently come to work on-time and not slack off, gamble or drink on the job, not attempt to bribe your supervisors for cushy assignments, doctor your time cards, or abuse any special work-rations, as well as keep your complaining down to a minimum? If you were a union member, you would be expected to put your AFL/CIO rivalries to the side for the duration, and everyone was expected to respect and willingly to work with the large number of women and minorities now in the navy yard. You would further be expected to purchase as many war-bonds as you could afford, and to give blood liberally and encourage other worker to do likewise. It was also a worker's duty to report “suspicious” activities and people to authorities. Above all, employees were expected to maintain a positive attitude to the war and to the sacrifices it required on the home front. To help workers' morale stay high, the BNY sponsored lunch-time rallies, entertainment, and boxing events. [These aspects of war work were suggested by a reading of The New York Times and The Shipworker, the in-house newspaper established by the Yard in November 1941, during the World War II years.]

Another fundamental element of labor relations in the navy yard was the issue of draft deferments. Warships could not all be built by inexperienced women, and the older stratum of the white and minority male work force. Recognizing this, the government granted deferments to navy yard positions as well as to other defense jobs for the war's duration. This need to keep a certain number of otherwise military-capable men at home became a major source of strife in the navy yards after the war. In June 1944, Congress passed the Veterans' Preference Act, which restated with more strength the rules on veteran preference to government jobs. For those workers who had left government service to join the military the law gave them reinstatement rights to any job for which they were qualified, with no time limits for applying. In 1945, fifteen per cent of government workers had veteran preference; by 1949, the number had risen to fourty-seven per cent, and veteran organizations took on a new importance as an interest group. Not only did the Brooklyn Navy Yard downsize its force after the war by letting go those “temporaries” brought on for the duration and six months but it also manipulated the efficiency ratings to release older, and deferred workers to bring veterans into the yard. The displaced employees felt themselves severely abused. [On the deferments, see NYT, 24 October 1942. On the 1944 act, see U.S.C.S.C., “History of Veteran Preference in Federal Employment, 1865-1955,” (Washington, 1955); Patricia Ingraham, The Foundation of Merit: Public Service in American Democracy (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1995). On the post-war layoff situation in the navy yard, see Brooklyn Eagle, 21 February 1946; 25 April 1946; 4 May 1946; 8 May 1946.]

After the war the navy yard entered a period where it performed only repair work, the first lenghty break in production since the Yard began the Penscacola in the mid-1920s. The Yard finished the Roosevelt and Kearsarge by March 1946, but it shunted off the unfinished Oriskany to a side pier and left it to sit for almost four years. By May 1946 the workforce had fallen to 35,000, and the Brooklyn Metal Trades Council let its collective displeasure be known in Washington, but to no avail. In July 1946 the Yard announced it would let another 19,000 go within the year, with the goal being to establish a peacetime force of about 9000. With the onset of the Korean and Cold Wars the Brooklyn Navy Yard reverted to a construction yard in the early 1950s. The Oriskany was completed and the Yard went on to build three super-carriers over the next ten years, finishing the last in late 1961. And, in the six years preceding its closure in 1966 the navy yard built six troop transports. [NYT, 4 May 1946; 9 July 1946. List of ships built.]

Back at peace, the Navy reverted to using local wage surveys to determine wages for its blue-collar work force. [For war-time wage determination, click here.] But now it coordinated its national and local bureaucracies. The Navy’s Office of Industrial Relations, set up during World War II, worked with local Area Wage Survey Committees to determine appropriate wage schedules. In 1962 the government adopted the prevailing-wage concept for its entire workforce in the Salary Reform Act, which set salaries according to the data found by annual surveys of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, an office of the Department of Labor. The wage schedule for the IVbs was made less complicated by the Classification Act of 1949 which reduced the number of services from five to two and lowered the number of grades within them. [Murray Nesbitt, Labor Relations in the Federal Government Sector (Washington: Bureau of National Affairs, 1976); Ingraham, The Foundation of Merit.]

In the years immediately following the war the government also passed legislation that criminalized striking by federal workers. Up to this point, the 1912 prohibition of a government worker belonging to an organization that asserted the right to strike the federal government held sway. In response to some poor wording in the constitution of the United Public Workers--the UFW's successor--that seemed to suggest that federal workers did indeed have the right to strike the federal government, Congress inserted language into payroll appropriations bills beginning in 1946 that made striking illegal and required employees to sign an affidavit that they would not strike, and in 1947 codified this restriction in the Taft-Hartley Act, effectively equating striking with being a member of a proscribed political party. [Nesbitt, Labor Relations; Spero, Government as Employer.]

As to the issue of union recognition, the Navy Department reverted to the shop committee system after the war, but the war experience in all the federal agencies had laid the ground for lobbying for recognition. During the 1950s bills were introduced into Congress annually to improve federal labor relations through union recognition of some sort, and ultimately, President John Kennedy responded in January 1962 by issuing an executive order giving workers the right to formal recognition, although this directive did not give unions the power to bargain over any work conditions set by law, and the government still retained the ultimate authority to resolve disputes (i.e., no outside arbitration). In the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the Brooklyn Metal Trades Committee won the resultant recognition election and began negotiating its first contract in August 1962. [Shop committee principles in the navy yard are laid out in Shipworker, 19 March 1947. Nesbitt, Labor Relations; Chantee Lewis, “The Changing Climate in Federal Labor Relations,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (91, March 1965); Lynda Tepfer Carlson, "The Closing of the Brooklyn Navy Yard: A Case Study in Group Politics" (Ph.D. diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1974); Theodore Zaner, “Did the Right to Bargain Collectively Precipitate the Closure of the Brooklyn Navy Yard?” Personnel Administration 30 (July-August 1967).]

But at least for the Brooklyn Navy Yard it was too little, too late, as the navy yards’ days were numbered. World War II produced an overabundance of shipyards and in the succeeding years as naval and commercial shipbuilding declined, the private shipbuilding association lobbied hard and viciously to be awarded the navy’s work, alleging the greater expense of navy yards in building and repairing warships. In 1964 and in 1974 Congress allotted 35 per cent, then 30 per cent of all naval conversion, alteration, and repair work to private shipyards, and in 1967 it stripped the navy yards of all future construction work. And, in 1964, the Johnson administration within weeks after the November election announced the first closing of a navy yard and it was the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the biggest and most expensive. It was shut down in June 1966. Over the rest of the century navy yards would be shut down one by one until as of now, only those at Norfolk, Portsmouth, Puget Sound and Pearl Harbor remain. [Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration, “The Use and Disposition of Ships at the End of World War II" A Report Prepared for the U.S. Navy Department and the U.S. Maritime Commission, printed for the use of the Committee on the Merchant Marine and Fisheries" (Washington: GPO, 1945), especially p. 205: “[T]he conclusion appears inescapable that the most satisfactory nucleus of shipbuilding skills will be maintained in the private yards.” Also: Lynda Tepfer Carlson, “The Closing of the Brooklyn Navy Yard”; Clinton Whitehurst, “Is There a Future for Naval Shipyards?” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (April 1978).]

John R

Stobo

©

February 2005