The standard definition of ‘object’ includes two meanings 1) a material thing that can be seen and touched. 2) a thing to which an action or feeling is directed. The object I’m puzzling out is more at home in the latter definition. However, by considering its materiality - or maybe conceit-ing its materiality - perhaps we can make better sense of how and why the absent object becomes the object of attention. It might be fair to say that we are dealing here with conceptual objects, what Mitchell calls ‘Idols of the mind’. However, this designation doesn’t necessarily foreclose interpretations or restrict these objects from the realm of the real, rather it allows us to explore how and where the imaginary and real collide.

I’m interested in the visitor experience in historic heritage sites. Increasingly, sites where events deemed historically important occurred are being used to mark the significance of what took place, in that place. What makes learning about history in such a particular place different from learning about it one mile up the road? Why do we want to go to where ‘it’ happened? I want to consider what is present in these heritage sites, but moreover what is absent. Let me first introduce you to what is present at Langtrees 181, Kalgoorlie Australia, and give a little background.

Langtrees Old House

Langtrees 181: 'Historic Bordello and Museum of Prostitution'

Prostitution plays a big part within Australian social and labour history, and many museums have begun to represent this. Where prostitution took a greater or more visible role in community, there it will be more accepted as part of local cultural heritage. This is certainly true of Kalgoorlie, an old mining town near Perth, where the local Gold mining Museum addresses commercial sex culture as an accepted part of frontier life. The importance of the sex industry in Kalgoorlie has engendered a rather unusual approach to local heritage, with the impetus coming from within the industry. Langtrees 181 claims to be the world’s only purpose built ‘Historic Bordello’. In 1998, Madam Mary-Anne Kenworthy obtained council approval for a ‘Historic Bordello and Museum of Prostitution’, and subsequently built a multimillion-dollar bordello on the site of a dilapidated tin-shed brothel on the main red-light drag. Today historical tours of Langtrees 181 have become the town’s key tourist attraction. Langtrees’ promotional material explains the heritage rationale: “The sex trade in Australia, particularly Kalgoorlie, has a unique and colourful history. Kalgoorlie's roots lie in the gold mining industry, when thousands of men flocked to the Kalgoorlie Goldfields in the late 1890s in their search for riches. That concentration of testosterone of course led to the introduction of an intense sex trade to satisfy the desire for 'female company’ many a miner required to sustain themselves in the harsh conditions of the Goldfields. Educational and interesting, this tour will take you on a journey through the origins of Kalgoorlie's sex trade.” [1]

Langtrees runs three tours a day and estimated visitor figures now reach as high as 220,000 tourists a year. [2] According to social historians Simon Adams and Raelene Francis, the visitor demographic ranges from young American tourists, to tour buses of pensioner groups. After the coaches leave, the workers arrive and the brothel is open for business as usual. Adams and Francis observe, “The tours are as much an advertisement for legalised prostitution and the sex industry as they are a voyeuristic peek behind the velvet curtains of a working brothel.” [3]

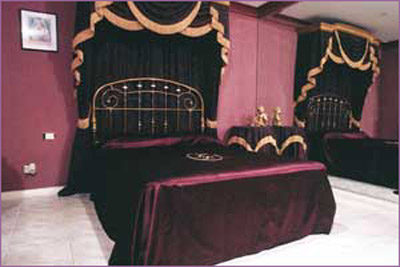

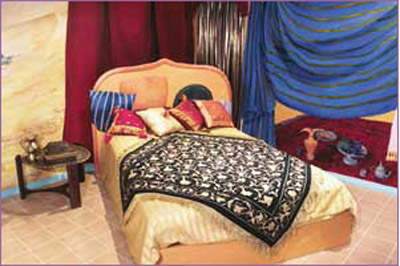

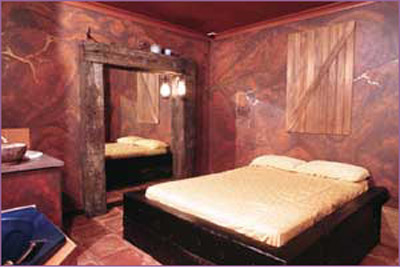

So what is behind the velvet curtain? Langtrees’ thirteen rooms are designed to chronicle the history of the local sex industry from the tents of the goldfields, right up to a millennium madam’s suite. Although there are a few historic artefacts such as brothel tokens and prints, the emphasis is on a guided tour of the heavily stylised rooms. Those devoted to the sex trade of the 19th century goldfields include a French and Japanese room, dedicated to the immigrant women who worked then, and the curiously decorated Afghan room, in honour of the Afghan camel drivers who provided water to the miners. The two rooms that interest me the most are the Coolgardie Tent room and the Great Boulder Shaft Room.

Left: Langtrees Love Nest (French Boudoir). Right: Heishen Room.

Left: Afghan Boudoir. Right: Madam's Suite.

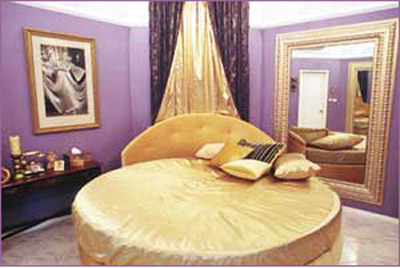

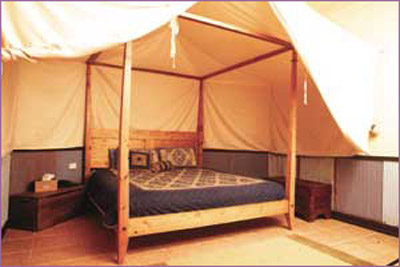

Left: Boulder Shaft Room. Right: Coolgardie Tent Room.

Draped with calico canvas the Coolgardie Tent room has simple decor; the corrugated tin on the walls include sections from the original brothel building. The guide will tell you “The Coolgardie Tent Room is a replica of one of the 70 brothel tents that littered the Coolgardie landscape during the major Australian gold rush in the 1890’s. The tents housed up to 150 working girls from a variety of countries and walks of life. These girls catered for over 30,000 miners, who often travelled hundreds of miles to visit the Goldfields ladies. The girls were always busy. They drank homemade gin and smoked opium in an attempt to make the job bearable."[4] The Great Boulder Shaft Room also has some historical material included within its paint-effect walls. To quote Langtrees, “Named after the first mine in the Kalgoorlie Goldfields, the ‘Great Boulder Shaft Room’ resembles an old mineshaft. The bed and mirror frames have been constructed from original jarrah railway sleepers and the mining pots (crucibles) were used for melting gold from the ore. The illusion of being in a long underground mineshaft has been created with cleverly positioned mirrors. We like to think of it as an endless tunnel of love. “[5]

These mock-historical interiors bring in questions of authenticity, simulacra and the Disneyfication of the past. For me they also suggest that the historical experience being sold by Langtrees doesn’t concern the historicity of artefacts or the material fabric of the premises. Having said this, some material objects matter more than others do. The prominence of the bed as an index of prostitution is a notable sign in the visitor experience. Plus the inclusion of some ‘genuine’ old bits and pieces such as railway sleepers and corrugated tin, perhaps lend an element of historical interest. However, I’d argue that it is what is not there, the absent object, which is the foremost object of attention.

I’m interested in these rooms as sites of cultural heritage, similar to reconstructions at National Trust historic houses. In such places, the object of attention is in the past and the purpose of the memorial space is to reflect on and learn about that history. One organisation devoted to this exercise is the snappily titled International Coalition of Historic Site Museums of Conscience (ICHSMC). This group of museums mark a historic event or phenomena on the site at which it took place, educating visitors through tours and museum display. Thirteen members include a workhouse in the UK, the Maison Des Esclaves, a key transit house for transatlantic slave trading on Senegal’s coast, and a Gulag Museum at Perm-36 in Russia. The ICHSMC believes that historic sites have “a unique power to inspire social consciousness and action”[6]; I’m interested in where that power comes from. The webpage on the Senegalese slave house states that although there are few historic artefacts, the rooms are a “mute reminder of the incalculable evil perpetrated by man’s inhumanity to man” and that the house has become an “international symbol of the horrors of racial slavery”.[7] Although the house is described as a ‘reminder’ and a ‘symbol’, I’d argue that it is more than a simple mnemonic device. The command of a historic site derives, in part, from a sense that the place retains the residual resonance of the events that occurred there. Material remains certainly act as evocative markers, but it is what is not there, the event in the past, that is the real object of attention.

Critiquing the ‘new rhetoric of world heritage’ Lynn Meskell coined the term ‘negative heritage’ for the memorialization of histories of political and real violence. Meskell defines negative heritage as “a conflictual site that becomes the repository of negative memory in the collective imaginary. As a site of memory, negative heritage occupies a dual role: it can be mobilised for positive didactic purposes (e.g. Auschwitz, Hiroshima, District Six) or alternatively be erased if such places cannot be culturally rehabilitated and thus resist incorporation into the national imaginary (e.g. Nazi and Soviet statues and architecture).”[8] Meskell’s negative heritage includes material culture that represents histories considered shameful or dangerous, it also involves absent objects, absent people, and the commemoration of things that are no longer there. Many negative heritage sites are places where human lives were taken, violence was committed, or bodies suffered. The visitor narrative might be as follows: “Extremities of human experience that are almost incomprehensible took place on this soil; by standing in this space and breathing in this air maybe I will comprehend them”. The cultural heritage of Langtrees 181 can be considered negative heritage, as there is a resistance to incorporate prostitution, as a historical and contemporary practice, into the cultural imaginary. However, I want to extend Meskell’s notion of ‘negative heritage’ to suggest an understanding of ‘negative-space heritage’. In many of her examples, and mine, absent historical objects provide the visitor focus. Within negative heritage there is some ‘thing’ missing, the site is where something is absent. Historic sites often generate the sense of being hallowed, haunting or uncanny; and understandably, these are conditions ripe for engendering iconoclash!

In an essay on iconoclash in the representation of the immaterial sacred Professor Severin Fowles looks at strategies in which the unseen spirit “is represented not by the presence of a tangible signifier but instead by a meaningful absence (which becomes its own dramatic signifier) made conspicuous by some sort of material frame.”[9] Within negative heritage sites, the material frame might be a deserted battlefield or empty prison cell, the object of meaning is the radical absence of human lives. The material frame of the meaningful absence in Langtrees 181 is the faux-historical walls and props. Rather than scrutinise these accessories, I want to concentrate on the negative space that they carve out, and explore what the meaningful absence signifies.

Treating the air inside a room at Langtrees as an object, we could make a pretty good guess at the chemical compounds that constitute its materiality. We could also do a phenomological interpretation - what in particular does the air of this room look, feel, sound and smell like? Does it look opaque with cigar smoke, and is it filled with sounds of physical exertion or saxophone music? Does it feel warm or icily air-conditioned? Does the air smell like perfume, coffee or bleach? However, when we’re in the realm of iconoclash maybe these types of explanations are less helpful. What I do find useful is the work of artist Rachel Whiteread.

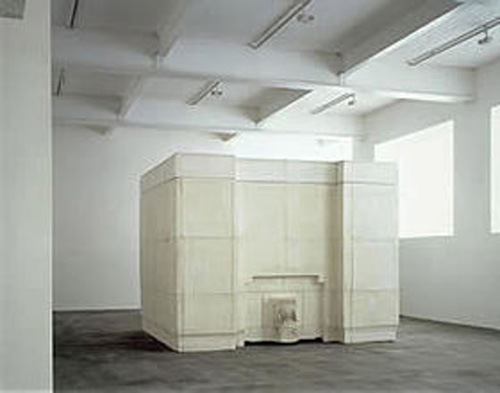

Rachel Whiteread's casts. Left: House, 1993. Right: Ghost, 1990.

Whiteread’s casts House, 1993, and Ghost, 1990, both capture architectural space, doing away with the material frame and solidifying the air within negative space. Playing between the cast and its mould, Ghost disturbs the categories of presence and absence, almost mocking materiality by substance-ing silent space. Uros Cvoro reads this work in relation to Derrida’s notion of the Trace. He writes, “The force of the trace emerges not only from placing presence under erasure, but also from destabilising absence as a category of meaning in the play between absence and presence…As traces of trapped space and destroyed spatiality, casts embody the compression and congealing of ‘life’, meaning and the spatial intervals necessary to sustain them.”[10]

Let’s try an experiment. What if we were to treat the Coolgardie Tent Room as a mould and cast an impression of the negative heritage caught in its material frame? Can we catch the spirits, ghosts and angels of history? What people, acts, exchanges and encounters are frozen in the cement-filled air? The air-turned-solid restricts access, spatiality is destroyed and the trace disorientates us; those with claustrophobia need a paper bag, and the ghosts caught in the cement turn sinister. Making palpable that which is unseen is an iconoclashtic move. In this case is doesn’t solve anything, but it reveals a tension between presence, absence and trace.

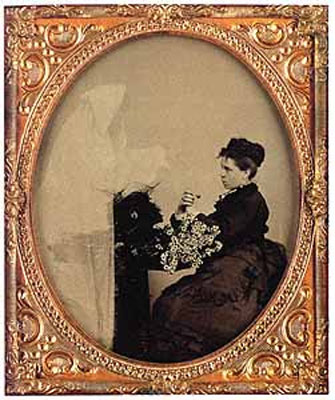

In an examination of capturing the invisible intangible Alison Ferris draws parallels between Whiteread’s Ghost and spirit photography in the 19th Century. This spiritualist pastime involved photographing portraits, which upon developing would reveal the presence of spectres, invisible to the human eye but registered by the sensitive photographic machinery. Ferris writes “In Ghost and Spirit Photography, recognition takes place where the visible and the invisible, the dead and the living, the past and the present overlap and are momentarily integrated.”[11] Again, the trace collapses binaries, confusing that which is animate and inanimate, producing an uncanny effect. Tom Gunning asserts that spirit photography was so disquieting because it “seemed to undermine the unique identity of objects and people … creating a parallel world of phantasmatic doubles alongside the concrete world of the senses." [12] So let’s try another experiment. Let’s mentally photograph the Coolgardie Tent Room with the spirit cameras of our minds and see what develops.

Tintype, Sixth-plate (2.75 x 3.25 inches) circa 1875

In the spirit photograph of the space there is an image of a man and woman having sex, there is also the attached knowledge that the act is one of commercial exchange. But who are the copulating couple? Are they from the goldfields, or from last week? Or perhaps they are a fantasy of the couple who will occupy the room in a few hours? Adams and Francis observe “Throughout [the tour] the emphasis is on both the historic and contemporary: Western Australia’s current laws governing prostitution are ridiculed, while one is asked to empathise with the ‘poor French girls’ who were lured to the brothels of Kalgoorlie under false pretences during the 19th century.”[13] The visitors’ object is suspended between the past of ‘long-ago’ and the past of ‘last night’. Crucially there is also the anticipation of ‘tonight’. What is the difference between old ghosts and new ones? What does it mean when the significant act isn't in the past but is the anticipation of one that is yet to happen? Is there a similar sense of morbid arousal in other historic sites of negative heritage? In negative heritage sites often the tag line is ‘never again’. Of course ironically they rely on mental reconstructions that replay the event again and again every day. Maybe the fantasy possibilities that this act of imagined ‘post-memory’[14] provides gives visitors the creeps; but maybe it gives them the hots?

* * * *

The Langtrees historical tours could be symptomatic of the recent phenomenon of cultural “musealization”[15], however, one can argue that the relationship between museums and commercial eroticism goes back a lot further. In fin de siècle cultural discourse, it is possible to trace an emerging relationship between bourgeois collecting practices and the medical discourse on psychosexual mania. Emily Apter argues “The mania of collecting and it’s increasingly refined, recherché’ developments – bric-o-bracmania, tableaumania, bibliophilia, vestigonomania – seem to have merged with the newly minted sexual aberration of erotomania, itself appropriated and dramatically exploited by the ‘temple of love’. From the courtesan’s boudoir to the speciality house of prostitution.”[16]

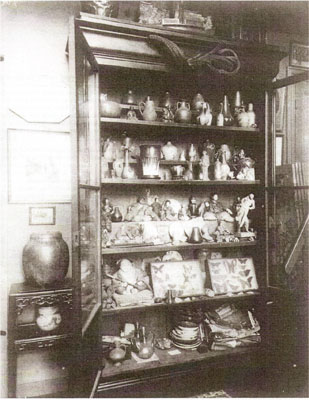

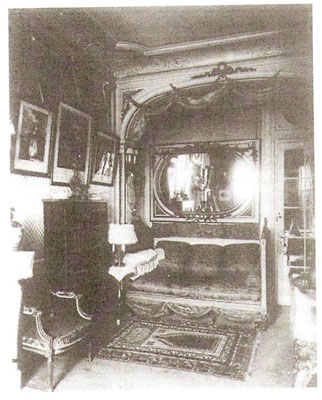

Eugene Atget. Left: Interior of Mr. B., collector, rue e Vaugirard, 1910. Right: Interior of Mile Sorel of the Comedie Francaise avenue des champs Elysees, 1910.

In the doctor’s examination room, the prostitute’s boudoir, the perverse couple’s bedroom, and the salon cabinet of curios, the collector as voyeur, as doctor, and as connoisseur of women, amasses a collection of treasures and pleasures. Apter calls this realm ‘the prostitutional cabinet’. She considers the scopophilic pleasure that visitors, viewers, voyeurs of the prostitutional cabinet derive. There is an emphasis on seeing without being seen. In Proust's Remembrance of Things Past, the perverse couple’s bedroom has a small oval window offering voyeuristic opportunity. The window is called a “vasistas” derived quite literally from Was ist das? What is it? What is the thing that you are seeing? What is the thing that you desire? In the spaces where the collector’s voyeurism and the spectacle of perverse bodies play out, Apter suggests the object of desire is the very secrecy of the contract that binds the spied-on couple.[17] Perhaps it is this that is the absent object of the Tent Room. Rather than bodies locked together, the spirit photograph captures the look exchanged between client and worker as money changes hands and the clandestine deal of commercial sex is done.

The complex configurations of commodity fetishism intersect and index on the body of the prostitute. Rather than a simple case of woman as oppressed commodity object, Apter argues for the possibility of power within prostitute’s position as object; as she is a connoisseur’s collectable, so too is she a collector of lovers. As we saw in our reading of Mitchell’s’ Image and idolatry the 19th century connoisseur collector became regarded as a fetishist. Mitchell writes, “The projection of the worshipper’s “life” into the fetish takes on the specific form of a projection of masculinity, a projection which results in the symbolic castration or feminization of the fetishist.”[18] The collector is ridiculed as effeminate, his obsession becomes a vice. Apter argues that as the discourses of erotomania and collecting fuse, a conversion takes place and as the prostitute becomes collector, so the connoisseur becomes prostitute. There is a slippage between collector and collectable; object becomes subject and vice versa. It’s tempting to consider how visitors at Langtrees might perform this slippage and how absent objects facilitate fantasies of identification.

The prostitutional cabinet as a fin de siècle phenomenon helps to place Langtrees 181 within a history of collecting and eroticism, within a heritage of museums and desire. In this paper, I’ve tried to work through some issues of how humans grasp intangible objects. Through a series of mental exercises, I’ve tried to imagine what is collected in negative heritage and what traces remain. What Langtrees 181 may show us is that with absent objects, matter doesn’t matter that much. What matters is the play between absence and presence, and the cognitive vertigo that this produces. The uncanny effect of the trace enables us to slip between object and subject, past and present, material and immaterial. It allows visitors to come away from a historic heritage site moved by some ‘thing’, which was not there.

bibliography:

Adams, Simon and Frances, Raelene, Lifting the Veil: the Sex Industry, Museum and Galleries, Labour History, Vol. 85, Nov 2003.

Apter, Emily, Cabinet Secrets: Fetishism, Prostitution, and the Fin de Siècle Interior, Assemblage, No. 9. (June 1989), pp. 6-19.

Buckley-Carr, Alana, Brothels' New Visitors Just Want to Look, The Australian, Edition 1, January 8th 2007.

Cvoro, Uros, The Present Body, the Absent Body, and the Formless, Art Journal, Vol. 61, No. 4. (Winter, 2002), pp.54-63.

Ferris, Alison, Disembodied Spirits: Spirit Photography and Rachel Whiteread’s “Ghost”, Art Journal, Vol. 62, No. 3 (Autumn, 2003), pp.44-55.

Fowles, Severin, On Being Unseen: The Secret Power of the Homunculus, Jan 2006, Unpublished.

Hirsch, Marianne, Past Lives: Postmemories in Exile, Poetics Today, Vol. 17, No. 4, Creativity and Exile: European/American Perspectives II. (Winter, 1996), pp. 659 – 686.

Huyssen, Andreas, Twilight Memories : Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia (New York: Routledge, 1995).

Meskell, Lynn, Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology, Anthropological Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 3. (Summer, 2002), pp, 557 – 574.

Mitchell, W.J.T. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987)

websites:

http://www.sitesofconscience.org

[1] http://www.langtrees.com

[2] Alana Buckley-Carr, Brothels New Visitors Just Want to Look, The Australian, Edition 1, January 8th 2007, pg 3

[3] Simon Adams and Raelene Frances, Lifting the Veil: the Sex Industry, Museum and Galleries, Labour History, Vol. 85, Nov 2003. Paragraph 18

[4] http://www.langtrees.com

[5] ibid.

[6] http://www.sitesofconscience.org

[7] ibid.

[8] Lynn Meskell, Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology, Anthropological Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 3. (Summer, 2002), pp, 557 – 574. Pg 558

[9] Severin Fowles, On Being Unseen: The Secret Power of the Homunculus, Jan 2006, Unpublished.

[10] Uros Cvoro, The Present Body, the Absent Body, and the Formless, Art Journal, Vol. 61, No. 4. (Winter, 2002), pp.54-63, Pg 56-57

[11] Alison Ferris, Disembodied Spirits: Spirit Photography and Rachel Whiteread’s “Ghost”, Art Journal, Vol. 62, No. 3 (Autumn, 2003), pp.44-55, Pg 52

[12] Tom Gunning, 1995, quoted in Ferris, ibid.

[13] Adams and Francis, Op. Cit.

[14] Marianne Hirsch, Past Lives: Postmemories in Exile, Poetics Today, Vol. 17, No. 4, Creativity and Exile: European/American Perspectives II. (Winter, 1996), pp. 659 – 686.

[15] See Andreas Huyssen, Twilight Memories : Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia (New York: Routledge, 1995)

[16] Emily Apter, Cabinet Secrets: Fetishism, Prostitution, and the Fin de Siècle Interior, Assemblage, No. 9. (June 1989), pp. 6-19, Pg 8

[17] Ibid, Pg 12

[18] W.J.T. Mitchell, Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987. pg 194.