| two journeys

the deaths and lives of ga 'fantasy coffins' |

home | |||||||||||||||||||

|

T H I N G

|

kevin dumouchelle | |||||||||||||||||||

|

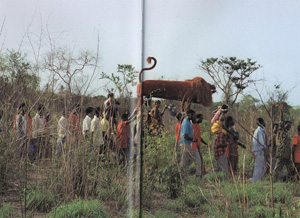

prologue Two endings serve as a beginning: In 1988 Esther Aalakailey Akuetteh, from Labadi, [Ghana] died at the age of ninety and was buried in a golden eagle. She belonged to that fierce class of ‘market women’ who made their fortune selling on the black market and exchanging contraband goods with Togo, and the Ivory Coast. Her other source of income was the Charter Healing Church, which she founded in Labadi with the Reverend Afutu in 1969 with the aim of healing sickness and disability through gospel music and prayer. Throughout the night before her funeral, the three hundred female members of the congregation (most of them market women like herself) sang gospel songs and on the morning of the funeral the Reverend Afutu arrived in a Cadillac to conduct the service. At the end of his hour-long sermon he made an appeal for donations and, as the women pressed forward towards the rostrum to hand over their money, he bellowed encouragement into his microphone: ‘Sow your money in the kingdom of the Lord and it will multiply! Alleluia![1] However, only a year earlier, a few towns down the road, the following scene unfolded: Mary Deddeh Attoh was the oldest woman living in Dansoman, a suburb of Accra. At eighty-five she was still conducting her own business and taking an active part in the affairs of the district. On her death, in 1987, she left behind eleven children, eighty-two grandchildren and sixty great-grandchildren. Her coffin, made in the shape of a chicken, accordingly had eleven chicks nesting beneath its wings. Mary was a Methodist and her burial service was conducted in a calm, dignified manner after the minister of Dansoman had delivered a funeral oration in the courtyard of the family concession. Kane Kwei’s coffins were barred from the church…where the service would otherwise have taken place; for both Protestants and Catholics, the use of these coffins smacks of fetishism, which they condemn.[2]

introductionBoth women elected to be seen going to their final rest in flamboyant coffins designed by the workshop of Kane Quaye, a carver whose workshop lies on the road between Accra and Tema, Ghana’s main port.[3] The coffins themselves, despite the deployment of a traditional, proverbial iconographic vocabulary, remain at once both artistic innovations and wholly functional objects with quite short life histories. They’re objects that die. At the same time, the differences seen in their two funerals speak to the strong reactions that Quaye’s creations evoke in his audience. They’re contested objects. Since the mid-1970’s, too, Quaye’s work has been shown in galleries in the West as art. They’re collected objects. Once created, Quaye’s coffins face two divergent paths: they are either soon filled with their earthly occupant, danced to their grave, and buried in the earth; or, they are themselves boxed up and shipped off to Europe or America, where they will be seen and remarked upon by thousands for many years, but remain themselves entirely empty. Quaye’s coffins, as celebratory performances of materiality, speak to a number of issues about the role that things play in social lives, while their two, divergent journeys raise interesting questions about the agency of such objects. Kane Quaye was born in Teshie in 1922. His father was an electrician on the colonial railway, but Quaye’s family wanted him to become a farmer. Sent at an early age to the interior for agricultural training, Quaye eventually snuck back to the coast, becoming an apprentice to his uncle, a carpenter. As a young man, the area around the outskirts of Accra was transformed by the construction of an airport (used by Allied forces on their way to the North African front), military camps and a deepwater port further along the road at Tema. Teshie, in other words, remained at the forefront of a modern Gold Coast – and this proved quite good for business. In 1951, Quaye’s grandmother passed away. “She had never traveled by plane, of course,” he said, “but after the airport was built she used to say that she often daydreamed about flying.”[4] Around the same time, his uncle designed a palanquin for the chief of Teshie in the shape of an eagle that “so impressed the headman of a neighboring village that he ordered one for himself in the shape of a cocoa pod…The chief never got to ride in his palanquin, dying before it was completed, and the cocoa pod served him as a coffin instead.”[5] Word of these unusual coffins soon spread, and Quaye opened his own workshop that same year. While elaborate funeral ceremonies have a long history in Ghana, they were once the preserve of chiefs, serving as expressions of ethnic identity, the power of the local state and performances of an area’s wealth. Now, however, “any member of a tribe could have one, if his family and friends could afford to pay for it – and what better way of honoring and thanking their fathers for their newfound prosperity.”[6] Among the Ga (the people of Accra and the coast specifically) “the dead are constantly present in…daily life…[They] believe in reincarnation within the family…a person’s spirit [cannot] rejoin its celestial family or become an ancestor capable of reincarnation unless it has undergone the appropriate burial rites. For a Ga it is better to incur lifelong debts than to cut back on funeral expenses.”[7] Coffins, one should note, “themselves were only introduced in the colonial period as a part of the Christian burial practice, and Kwei’s represent ebullient innovation and a monument to his clients’ worldly prestige based on this relatively new form.”[8] Indeed, Swiss and German missionaries introduced new carpentry techniques along with Christianity in the nineteenth century. While now an overwhelmingly Christian country, burial in Ghana “is [also] closely associated with ancestor worship and is the single most important community activity, taking place every Friday and Saturday of the year. It is the ultimate manifestation of deep-rooted tradition.”[9] Quaye, nevertheless, insisted until his death (in 1992) that “his art had not evolved out of African customs or Ghanaian tradition.”[10] Given the social change in Ghana in the last century, if not Quaye’s lifetime itself, he certainly makes a compelling case.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

T H E O R Y

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| When people die, they like to travel to heaven in different ways – some by land, some by sea and some by air. | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

That one is for a rich cocoa farmer. He wants to take his wealth with him when he dies.[12] — Kane Quaye |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

objects that die Innovations in their own right, “the…purpose of Kane Kwei’s coffins was to glorify the dead by displaying the source of their success in life.”[13] Most of his clients were from the Ashanti region (the wealthiest area in the country.)[14] As one art historian notes, “Quaye’s innovation is partly indebted to the streets of West Africa. On a daily walk through any market area, direct display is ever present. Unlike a supermarket…the outdoor market relies on open display and pictorial communication.…Paying homage to the commonplace, the coffins have an immediacy and lack of pretense that brought them clients with unexpected purposes in mind.”[15] Unlike death in the West (which occurs largely out of sight, at a sanitized remove) death in West Africa remains a comparatively immediate experience, while funerals remain fixed, communal weekend celebrations.[16] Quaye offers his patrons a limited number of models, which “makes for efficiency in the workshop. Unlike most traditional African art and furniture, Kane Kwei’s coffins are carpentered, like European furniture, rather than carved from a single piece of wood. (Coffins themselves are rare in traditional African culture.) They are naturalistically painted with enamel paint, and are at least 5 ½ feet long, with a removable lid and an upholstered interior including a mattress and pillow.”[17] His art, however, “has a destiny…that few artists have had to face since the ancient Egyptians: the works that his local clients accept are buried and disappear.”[18] This problem raises the first central issue to which the coffins speak: the shape of the ‘biography’ of an object. These objects certainly have social lives. As they are danced to their graves, “at the human level, transition is given a fictive permanence: the coffins in their numerous forms…all of which symbolize class, stature, profession and, above all, a new consciousness, are engrained in collective memory. Since these coffins are ‘danced’ all over the community before being committed to earth, the form, color and visual splendor become markers that society will find difficult to forget or dismiss.”[19] Hoskins states “things can be said to have ‘biographies’ as they go through a series of transformations from gift to commodity to inalienable possessions, and persons can also be said to invest aspects of their own biographies in things.”[20] In elaborating a theory of ‘objectificication,’ (to “overcome the dualism in modern empiricist thought in which subjects and objects are regarded as utterly different and opposed entities”) Tilley notes how, “through making, using, exchanging, consuming, interacting and living with things people make themselves in the process.”[21] As ‘artifacts’ such objects “may…objectify a particular event or transaction, or aspects of the identity of the transactor. They can also objectify particular places where they were made or transacted or places from which the raw materials were obtained. The artifact can thus be a place, a landscape, a story or an event.”[22] Ultimately, it is hoped, object biographies should allow one to “reach a fuller critical appreciation of the manner in which those things are ontologically constitutive of our social being.”[23] The most remarkable aspect of a coffin’s life, however, remains its death. “The problems in imagining the body,” Stewart argues, continuing the earlier elaboration of the ‘artifact,’ “are symptomatic of the problems in imagining the self as place, object and agent at once.”[24] “The idealized body,” she continues, “implicitly denies the possibility of death – it attempts to present a realm of transcendence and immortality…This is the body-made-object, and thus the body as potential commodity, taking place within the abstract and infinite cycle of exchange.”[25] She defines the ‘souvenir’ as a witness to lost materiality. “Here we find the structure of Freud’s description of the genesis of the fetish: a part of the body is substituted for the whole, or an object is substituted for the part, until finally, and inversely, the whole body can become object, substituting for the whole.” Such objects have a “surplus of signification, [which are] experienced, as…catastrophe and jouissance simultaneously.”[26] Always incomplete and partial (so that it can be “supplemented by a narrative discourse”) “the souvenir is destined to be forgotten; its tragedy lies in the death of memory, the tragedy of all autobiography and the simultaneous erasure of the autograph.”[27] Can we then understand Quaye’s coffins as ‘souvenirs’? As objects into which the expired containers of subjects are placed, the coffins certainly straddle an interesting existential line. Bataille, in considering the origin of the object (as “strictly alien to the subject, to the self still immersed in immanence”) maintains “we do not know ourselves distinctly and clearly until the day we see ourselves from the outside as another. Moreover, this will depend on our first having distinguished the other on the plane where manufactured things have appeared to us distinctly.”[28] The corpse, at the literal center of Quaye’s work, “is the most complete affirmation of the spirit. What death’s definitive impotence and absence reveals is the very essence of the spirit, just as the scream of the one that is killed is the supreme affirmation of life. Conversely, man’s corpse reveals the complete reduction of the animal body, and therefore the living animal, to thinghood.”[29] Since, as Baudrillard states, “we cannot live in absolute singularity, in the irreversibility signaled by the moment of birth…it is precisely this irreversible movement from birth towards death that objects help us to cope with.”[30] Indeed, he continues: The object is the thing with which we construct our mourning: the object represents our own death, but that death is transcended (symbolically) by virtue of the fact that we possess the object; the fact that by interjecting it into a work of mourning – by integrating it into a series in which its absence and its re-emergence elsewhere ‘work’ at replaying themselves, continually, recurrently – we succeed in dispelling the anxiety associated with absence and with the reality of death. Objects allow us to apply the work of mourning to ourselves.[31] Quaye’s coffins arose in an era in which individuality, for the first time, became an important part of West African culture and arts. Susan Vogel suggests “new kinds of funeral arts have appeared in answer to this desire to be individually remembered. Traditional graves were usually unmarked and located in rarely visited places, and cemeteries, if they existed at all, were small and simple; memorials to the dead were usually in or near the village, away from the place of burial.” Quaye’s innovation was to add to these elements “the dimensions of personal history, character, appearance and individual achievements.”[32] contested objects“The November 1997 funeral of a taxi driver, Holala Nartey, is a point of reference. For most of his career, Nortey drove an old Mercedes-Benz sedan for a hotel in Accra. When he died at sixty-three, a Mercedes coffin was purchased by his family. Three days of celebration brought together nearly four hundred people – his four children, ten grandchildren, coworkers, neighbors, friends and relatives. ‘Sponge ladies’ prepared the body, and then columns of mourners walked aroud his funeral bed to praise him, sob, vent anger, or ask him for help once he was established in the next life. Outside the house, crowds of friends and family visited, danced and helped themselves to food. On Sunday, eight pall-bearers lifted Nortey’s body in the Mercedes coffin as the dead proceeded around town to say goodbye. An older woman led the way, offering libations of palm wine on the ground as the procession moved. They moved past the Victory Spot Bar, the Congo Café, and the Step by Step restaurant and finally began the descent down a rugged road to the public cemetery. The crowd watched as the coffin was placed six feet down and covered with soil.”[33] What’s missing from this description of Nartey’s funeral remains any indication of whether or not his church reacted to the use of such a starkly materialist depiction for his final rest. (The Mercedes shape is usually reserved for wealthy clients but often barred from the inside of churches themselves.) How might we understand such symbolism? “Kane Kwei never went to primary school, and it is quite safe to say that when he made his first representational coffin he had never heard of Claes Oldenburg,” Vogel argues. “His most frequent commissions are neither surreal, comical, nor kitsch: they are coffins, made for his clients’ final rest. They are also matter-of-fact depictions of things in his and his clients’ daily lives…Kane Kwei’s art does not distance its viewers from the real world…Significantly, it makes no distinction between natural objects (plant and bird forms) and manufactured goods of European origin (airplanes and cars, or even villas): for the coffin-maker and his patrons, all these things are part of the surroundings.”[34] At the very least, the Mercedes is not a critique of materialism but, rather “a wholehearted celebration of it. The Mercedes must be understood as the preeminent African symbol of wealth, status and respect.”[35] In the end, “elaborate, expensive coffins and funerals, though frowned upon by Christian churches, express a traditional ideal of celebrating the family by honoring the dead…The modern art of Kane Kwei permits his patrons to uphold traditional values publicly through a conspicuously untraditional means.”[36] Conflict over the coffins, then, speaks to Latour’s concept of ‘iconoclash:’ “when one does not know, one hesitates, one is troubled by an action for which there is no way to know, without further enquiry, whether it is destructive or constructive.”[37] Their unusual iconography arouses the suspicion of certain Christian churches, resulting in what Latour might label a ‘Type B’ iconoclash. “What they fight,” he offers, “is freeze-framing, that is, extracting an image out of the flow, and becoming fascinated by it, as if it were sufficient, as if all movement had stopped.”[38] Accusations of “fetishism” certainly mirror this standard. At the same time, ‘iconoclash’ offers an interesting way of considering the coffins’ second journeys: as “art.” Their placement in a gallery context matches Latour’s ‘Type D’ iconoclash, which “destroy[s] not so much out of a hatred of images but out of ignorance, a lust for profit and sheer passion and lunancy.”[39] The second life of Quaye’s coffins mirrors the travails of “those African objects which have been carefully made to rot on the ground and which are saved by art dealers and thus rendered powerless – in the eyes of their makers.”[40] objects that are collected In 1973 the workshop received a visit from an American lady who owned a gallery in Los Angeles. The woman was so taken by Kane’s creations that she put in an order for seven coffins for display in her gallery. [41] In addition to being markers of individual social, religious, ethnic and class identity, and as potential sources of conflict, Quaye’s coffins also perform “art” for Western audiences, opening up a third area to which they contribute to a discussion of materiality. Without their purposive bodies inside (and, in particular, when commissioned and carved explicitly for export) Quaye’s pieces work as (bizarrely modern) ‘antiques,’ in Baudrillard’s classificatory system. The “antique object,” he writes, “no longer has any practical application, its role being merely to signify.”[42] But what does a fancifully painted, unusually carved coffin from Ghana signify in a Western gallery context? Baudrillard continues: “every antique is beautiful merely because it has survived, and thus become the sign of an earlier life.”[43] On some level, then, the coffins might be playing to a particularly Western, primitivist discourse – rendering Africa as signifier of a ‘past,’ ‘earlier’ life – even though Quaye’s art remains very much a 20th-century innovation. In this regard, Steiner quite rightly warns one to remain conscious of the “fickleness of taxonomy and the subjectivity inherent in the construction of categories of art and the sign system(s) of an art world.”[44] At the same time, his wider concerns are also echoed in the coffins’ second journey. “In their zeal to explore the social identity of material culture,” Steiner writes, “many authors have attributed too much power to the ‘things’ themselves, and in doing so have diminished the significance of human agency and the role of individuals and systems that construct and imbue material goods with value, significance and meaning.” Indeed, he continues, “the point is not that ‘things’ are any more animated than we used to believe, but rather that they are infinitely malleable to the shifting and contested meanings constructed for them through human agency.”[45] Indeed, if the coffins might have been considered to have any agency, in and of themselves, in their “traditional” context (whatever that may mean) they appear to have none, corpse-less, in Western galleries. The coffins, indeed, speak to the difficult and ill-defined border between ‘object’ and ‘art.’ “A funeral object transformed into sculpture is seen as an odd choice for contemporary art by some African observers,” one curator notes. “Made by carpenters for clients who expect the coffin to be seen only for a short time, it has an awkward air of unfulfilled purpose when not put to its intended use.”[46]

the woman was so taken by Kane’s creations that she put in an order for seven coffins for display in her gallery.

conclusion Kane Quaye’s inventive arts certainly have biographies of their own, which speak to the origins and roles of objects in social life through death, conflict and art, while offering intriguing questions about the agency of such objects. A final, curious aside about one of the first coffins commissioned for display in the U.S. serves as a closing coda. In describing her late 1990s show in Seattle, a curator notes that the Seattle Art Museum “replaced a Mercedes coffin that toured in the exhibition Africa Explores in 1991 and had been damaged by being packed and moved frequently in a manner completely unforeseen by its makers.”[47] We are left to speculate about what happens to such a purposeless coffin when it, in turn, dies. bibliographyBataille, Georges. Theory of Religion. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Zone Books, 1992. Baudrillard, Jean. The System of Objects. New York: Verso, 2005. Beckwith, Carol, and Angela Fisher. African Ceremonies. Vol. 2. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999. Burns, Vivian. "Travel to Heaven: Fantasy Coffins." African Arts 7, no. 2 (1974): 24-25. Hoskins, Janet. "Agency, Biography and Objects." In Handbook of Material Culture, edited by Chris Tilley, Webb Keane, Susanne Küchler, Mike Rowlands and Patricia Spyer, 74-84. London: Sage Publications, 2006. jegede, dele. Contemporary African Art: Five Artists, Diverse Trends. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2000. Kasfir, Sidney Littlefield. Contemporary African Art. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000. Kopytoff, Igor. "The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process." In The Social Life of Things, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 64-94. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. Latour, Bruno. "What Is Iconoclash? Or, Is There a World Beyond the Image Wars." In Iconoclash: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion and Art, edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, 1-37. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2002. McClusky, Pamela. "Riding into the Next Life: A Mercedes-Benz Coffin." In Art from Africa: Long Steps Never Broke a Back, edited by Pamela McClusky, 245-52. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 2002. Mitchell, W. J. Thomas. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. Pels, Peter. "The Spirit of Matter: On Fetish, Rarity, Fact and Fancy." In Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces, edited by Patricia Spyer, 91-121. New York: Routledge, 1998. Picton, John. "Coffins and Funeral Art." In An Anthology of African Art: The Twentieth Century, 126-29. New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2002. Secretan, Thierry. Going into Darkness: Fantastic Coffins from Africa. Translated by Ruth Sharman. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1995. Soppelsa, Robert T. "Review: A Life Well-Lived, Fantasy Coffins of Kane Quaye." African Arts 28, no. 2 (1995): 74-75. Steiner, Christopher B. African Art in Transit. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ———. "Rights of Passage: On the Liminal Identity of Art in the Border Zone." In The Empire of Things: Regimes of Value and Material Culture, edited by Fred R. Myers, 207-32. Oxford: James Currey, 2001. Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1993. Tilley, Chris. "Objectification." In Handbook of Material Culture, edited by Chris Tilley, Webb Keane, Susanne Küchler, Mike Rowlands and Patricia Spyer, 60-73. London: Sage Publications, 2006. Vogel, Susan Mullin. "Introduction: Digesting the West." In Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, edited by Susan Mullin Vogel, 14-31. New York: The Center for African Art, 1991. ———. "New Functional Art: Future Traditions." In Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, edited by Susan Mullin Vogel, 94-113. New York: The Center for African Art, 1991. [1] Thierry Secretan, Going into Darkness: Fantastic Coffins from Africa, trans. Ruth Sharman (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1995), 80. [2] Ibid., 96. [3] Early spellings of Quaye’s name were occasionally rendered as “Kane Kwei,” a convention here retained only in direct quotation. [4] Ibid., 14. [5] Ibid.. [6] Ibid., 18. [7] Ibid., 7. [8] Sidney Littlefield Kasfir, Contemporary African Art, World of Art (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000), 44. [9] Secretan, 22. [10] Ibid., 9. [11] Ibid., 20. [12] Vivian Burns, "Travel to Heaven: Fantasy Coffins," African Arts 7, no. 2 (1974). [13] Secretan, 20. [14] Burns. [15] Pamela McClusky, "Riding into the Next Life: A Mercedes-Benz Coffin," in Art from Africa: Long Steps Never Broke a Back, ed. Pamela McClusky (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 2002), 249. [16] Soppelsa notes: “The standard Western practice of presenting the deceased as if in sleep appears not to be a concern in southern Ghana. A body placed in the lobster, for example, would be slightly bent at the waist, as if it were resting in a reclining chair.” Robert T. Soppelsa, "Review: A Life Well-Lived, Fantasy Coffins of Kane Quaye," African Arts 28, no. 2 (1995). [17] Susan Mullin Vogel, "New Functional Art: Future Traditions," in Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, ed. Susan Mullin Vogel (New York: The Center for African Art, 1991), 98. [18] Ibid. [19] dele jegede, Contemporary African Art: Five Artists, Diverse Trends (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2000), 53-54. [20] Janet Hoskins, "Agency, Biography and Objects," in Handbook of Material Culture, ed. Chris Tilley, et al. (London: Sage Publications, 2006), 74. [21] Chris Tilley, "Objectification," in Handbook of Material Culture, ed. Chris Tilley, et al. (London: Sage Publications, 2006), 61. [22] Ibid., 70. [23] Ibid., 71. [24] Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1993), 132. [25] Ibid., 133. [26] Ibid., 135. [27] Ibid., 151. [28] Georges Bataille, Theory of Religion, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Zone Books, 1992), 29, 31. [29] Ibid., 40. In Pel’s words, “not only are humans as material as the material they mold, but humans themselves are molded, through their sensuousness, by the ‘dead’ matter with which they are surrounded.”Peter Pels, "The Spirit of Matter: On Fetish, Rarity, Fact and Fancy," in Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces, ed. Patricia Spyer (New York: Routledge, 1998), 101. [30] Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects (New York: Verso, 2005), 103. [31] Ibid., 104. [32] Susan Mullin Vogel, "Introduction: Digesting the West," in Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, ed. Susan Mullin Vogel (New York: The Center for African Art, 1991), 27-28. [33] McClusky, 250. [34] Vogel, “Introduction: Digesting the West,” 98-99. [35] Ibid., 99. [36] Vogel, “New Functional Art,” 100. [37] Bruno Latour, "What Is Iconoclash? Or, Is There a World Beyond the Image Wars," in Iconoclash: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion and Art, ed. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2002), 16. [38] Ibid., 27. [39] Ibid., 29. [40] Ibid., 30. [41] Secretan, 19. [42] Baudrillard, 77. [43] Ibid., 88. [44] Christopher B. Steiner, "Rights of Passage: On the Liminal Identity of Art in the Border Zone," in The Empire of Things: Regimes of Value and Material Culture, ed. Fred R. Myers (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), 229. [45] Ibid., 210. [46] McClusky, 250. [47] Ibid. |

||||||||||||||||||||

| home | ||||||||||||||||||||