On a farmland-turned-community-run school on Maple Hill in Vermont, an argument broke out between a local woman and man from out of town. Amidst the din of working cranes and trucks, the exchange went something like this:

Woman: You have no right to take this; it doesn’t belong to you.

Man: I understand your concerns; in fact I have quite a bit of sympathy for you.

Woman: Well, good, then leave this where it belongs: on the LAND.

Man: Miss, the stone is coming with me.

And perhaps after the sharing of a few more choice words, the argument ended and the fourteen and half-ton stone was lifted by a crane and placed into the bed of a New York City-bound truck. So, why all this fuss over such a big rock?

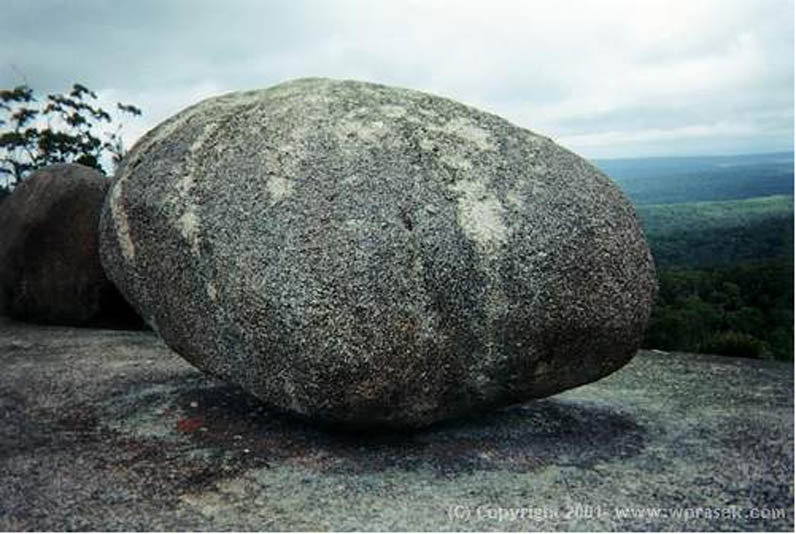

In September of 2003, land artist, Andy Goldsworthy, received funding to begin work on a permanent installation titled “Garden of Stones.” Waiting out a severe winter, Goldsworthy began canvassing the land north of New York, stretching out to Vermont in search of his “family” of rocks.

Beginning in the 1960’s, Land Art, also known as Earth Art or Earthworks, has been seen as an attack “on the embalming of raw nature by the aesthetics of landscape. Of all the genres of painting, landscape with its window view to the world, its dependence on the illusion of depth was arguably the one furthest from two-dimensional abstraction. Even flattened out, its pastoral lyricism was at the opposite pole from the street-smart edginess that agitated New York Abstract Expressionism.” Simon Schama writes that, “Land art was to be landscape’s comeuppance. The place would own the beholder, not the other way around.”[1] Well-known artists from this group are Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt and Michael Heizer. Andy Goldsworthy’s work, both permanent and ephemeral, has been displayed all over the world. And here on Maple Hill in Vermont, Goldsworthy must reaffirm his interest in social landscapes, welcoming the collaborations with both supportive and angry local farmers, teachers and residents. It is this collaboration with the social landscape that Schama writes aids in “pulling into his art the densely packed memories of human and animal occupation, limned through old hedges, cart tracks and sheepfolds.”[2]

Tim Ingold in his article “Materials Against Materiality” argues that “the forms of things are continually generated and dissolved within the fluxes of materials across the interface of the substances and the medium that surrounds them. Thus things are active not because they are imbued with agency but because of the ways in which they are caught up in these currents of the lifeworld.”[3] He continues:

Whereas the physical world exists in and for itself, the environment is a world that continually unfolds in relation to the beings that make a living there. Its reality is not of material object but for its inhabitants. It is in short, a world of materials. And as the environment unfolds, so the materials of which it is comprised do not exist—like the objects of the material world- but occur. Thus the properties of materials, regarded as constituents of an environment, cannot be identified as fixed, essential attributes of things, but are rather processual and relational. They are neither objectively determined nor subjectively imagined but practically experienced. In that sense every property is a condensed story. To describe the properties of materials is to tell the stories of what happens to them as they flow, mix and mutate.[4]

Ingold’s notion that properties of materials are not attributes-fixed and steady-but rather histories developed over engagements in the currents of the environment aligns with Goldsworthy’s thoughts on his work: “A long resting stone is not an object in the landscape but a deeply ingrained witness to time and a focus of energy for its surroundings.”

After months of seeking, Goldsworthy identified his stones, and began to experiment with ways of hollowing them out. In total Goldsworthy had selected twenty stones, ranging in weight from 3 tons to 15 tons. In Branford, Connecticut, Goldsworthy began to collaborate with Ed Monti, a seventy-year old man who drives to the quarry every day from Quincy, Massachusetts. Monti stands on top of a milk crate protected somewhat by a yellow safety coat and a welder’s helmet. He uses a shoulder-mounted lance, six feet long, to burn holes into the center of Goldsworthy’s stones. Goldsworthy kept a diary of the project in which he wrote the following passage:

The stones have come from areas cleared for farms and homes. I prefer to take them from places like this rather than from where they have been rooted in woods. These glacier boulders have had a long and, at times, violent past—both natural and man-made. Granite originated in fire at the earth’s core and rose to the surface where it has been split, carried and worn down by glaciers. Farmers pulled out whatever they could to make fields, blasting those that they couldn’t remove. When bulldozers arrived, the big stones were pushed to the edges of the fields intact, and this is the kind of boulder that I am lifting [using]. Without machines, these stones would not be there. Underlying the pastoral calm and beauty of a field is the destructive or creative violence of stones and trees being ripped out to make farmland…my working of the stones is a continuation of the journey these stones have made so far. They have a history of movement, struggle and change…[5]

Stones articulate moments of mourning in Judaism. Jewish law mandates that a tombstone be prepared for the deceased to prevent forgetting and to protect against potential desecration of the burial ground. The story of Rachel, wife of Jacob, introduced in Genesis 29:17, gives the foundational example of the use of stones during the mourning process. Rachel, while traveling on the road to Bethlehem, went into labor with her second son and died during childbirth. Jacob buried Rachel on the road where she died; his sons placed eleven stones atop the earth that covered her body, while Jacob placed one single, large stone.

The practice of placing small stones on burial sites, with or without tombstones, seems to trace back to Jacob’s gesture. Though it is now common practice to have inscribed tombstones made for the deceased, visitors to Jewish cemeteries will still often place small stones over the inscribed plaque. The stone is used to leave a trace of the visit, to articulate the visitor’s lack of forgetting.

Many memorials to the Holocaust can often be seen punctuated by small stones left by visitors. But in lower Manhattan Andy Goldsworthy’s “Garden of Stones” leaves the trace for you. Eighteen (in Hebrew every letter also possesses a numerical value: Chai has the corresponding number eighteen, and is known to many in the traditional toast "L'chaim" - to life!) of his twenty hollowed out stones form the narrow memorial garden at The Museum of Jewish Heritage a self-described “Living Memorial to The Holocaust.” (The two other stones that he lifted from Vermont were used in practice rounds for Monti’s hollowing out process). The stones after leaving Monti’s quarry traveled to a Brooklyn holding yard, awaiting their crane-enabled flight into air and onto the second story rooftop deck of the Museum. To complete the project, Goldsworthy filled the hollowed stones with soil and planted six-inch dwarf oak trees into each stone. For the opening reception of the garden, some Holocaust survivors and their family members were invited to plant the dwarf trees. Goldsworthy’s mother and sister, not survivors and not Jewish, also participated in the planting of one of the trees. A review of the garden that appeared in the September 22, 2003 issue of The New Yorker states:

The commission from the Museum of Jewish Heritage (in collaboration with the Public Art Fund) is in essence an attempt to realize a natural process of catastrophe and redemption. No one encountering the stone garden will think it the work of a decorative artist. It is instead an encounter with the elemental.

The white scuff marks he has left on them [the stones] testify to their many migrations: from fields near Barre, Vermont, where Goldsworthy and Ehrenberg [project manager] discovered them, to the Connecticut quarry where they were hollowed…finally…to Battery Park…onto the roof of the museum…Wandering stones seems right for a Jewish memorial garden, especially one that faces outward across the broad slate-green river to merciful stopping places: Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty.[6]

...

...

The symbolic register on which Goldsworthy’s work is now lodged is further emphasized by the museum’s literature about the garden:

Garden of Stones reflects the inherent tension between the ephemeral and the timeless, between young and old, and between the unyielding and the pliable. More importantly, it demonstrates how elements of nature can survive in seemingly impossible places…Goldsworthy brings stone and trees together as a representation of life cycles intertwined. As a living memorial, the garden is a tribute to the hardship, struggle, tenacity, and survival experienced by those who endured the Holocaust. This contemplative space, meant to be revisited and experienced differently over time as the garden matures, is visible from almost every floor of the Museum. The effect of time on humans and nature, a key factor in Goldsworthy's work, is richly present in Garden of Stones, as the sculpture will be viewed, as well as cared for, by future generations.[7]

I came to the garden with questions: How will 18 stones help me contemplate, reflect and remember? How am I to memorialize an immemorial event by means of entering this space populated by huge stones and tiny trees? For a project that seemingly sprung out of an interest in the material of stone, how are we left with only the symbolic capabilities of the material?

In the concluding chapter of Art and Agency, Alfred Gell discusses the transient nature that events have due to the continuum of time and our correspondingly modified perspectives.

The same event, as possible future event, as a present event, which is being experienced, and as past event, which can be recalled, remains one event, but as our temporal perspective on this event shifts, the event undergoes a series of modifications from the standpoint of the cognitive subject. It is seen through various thicknesses of future and past time, which alters its appearance, its temporal patination, so to speak.[8]

Current temporal perspectives on the events of the Holocaust and WWII are seen through a “thickness of the past,” which Gell argues forces the event to undergo modifications from the perspective of the cognitive subject. Moreover, these events are not only seen through the thickness of past but also through the historical collections, displays and monuments that strive to document the occurrences.

Carvings, made in New Ireland as part of mortuary rituals, known as Malangans, are gradually imbued with life as they are being carved and painted. Alfred Gell writes that “the process of making the carvings coincides with the process of reorganization and adjustment through which local society adjusts to the subtraction of the deceased…” The carvings, which “inscribe anticipated affinal alliances,” are displayed for a brief period of time at the culmination of the ritual, after which they are sold for shell money. The selling of the Malangan is coequal with its death. The killed Malangan can now be remembered and those in attendance of the ritual who made appropriate payments receive what Gell calls the “right to reproduce not just the visible form of the Malangan but the social relations which the form indexes.” The carving serves as a “repository of past ‘social effectiveness’ accumulated and contained, while as a spectacle, an exterior, the Malangan projects the future that these past relationships will produce as a result of the legitimization of certain anticipated relationships that the Malangan ceremony enables.”[9] Moreover, Gell argues that there are in fact two types of Malangans: the kind that are “walking about, making gardens…marrying and having children” and the Malangans that are in collections across the world. This is to say that memories of the object have more agency than the objects themselves.

But Goldsworthy’s stones are different in the sense that their material permanence, and not what was materially inscribed upon them, is, in fact, supposed to be socially relevant: the stones do remain despite the fact that memories, like lives, will fade. According to the museum, the future caretakers of the garden will also be caretakers of the memories these stones (symbolically) encapsulate: by caring for the garden, one is caring for memory. Unlike the argument that two types of Malangan exist, the Garden of Stones seeks the convergence of memory and material. Visitors to the garden see the stone’s qualities of stability, endurance and strength and want their memories to be of that same substance. It could be said then, following this line of thinking, that this desire to perpetuate memory into the far off distance of time (and ‘never forget’) imbues the garden with its agency.

But this is where I would like to the think that the material protests, causing a visitor like myself to pause and say, “but really, how does this group of stones relate to my mourning, my remembrance?” If “things are alive and active,” as Ingold writes, it is not “because they are possessed of spirit [or in this case memory]…but because the substances which they comprise continue to be swept up in the circulations of the surrounding media that alternately portend their dissolution or… ensure their regeneration.”[10] Therefore it is not that these stones, when used as planters for dwarf trees whose soil has mixed with the hands of survivors, are imbued with agency that allows this site to be a “living memorial.” Rather, what lives here, in the Garden of Stones, is the ever-developing history of the material—not so much how the stones have migrated from place to place—but more so how in each place the stoniness of the stone underwent some modification and redefinition. Taking seriously the material of this memorial affords one the opportunity to allow for changes in our memory, allowing memory to be experienced both out in the world as well as inside, internally.

references

Gell, Alfred. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Ingold, Tim. “Materials Against Materiality” in Archaeological Dialogues 14. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Schama, Simon. “Garden of Stones” in Passage, by Andy Goldsworthy. New York: HNABooks, 2004.

[1] Schama, Simon, “Garden of Stones” in Passage, by Andy Goldsworthy (New York: HNA Books, 2004), 60.

[2] Schama, 60.

[3] Tim Ingold, “Materials Against Materiality” in Archaeological Dialogues 14. (Cambridge University Press, 2007), 14.

[4] Ingold, 14.

[5]Andy Goldsworthy, Passage (New York: HNA Books, 2004), 63.

[6] Schama, 61.

[7] http://www.mjhnyc.org/visit_gardenofstones.htm

[8] Gell, Alfred. Art and Agency (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 238.

[9] Gell, 227.

[10] Ingold,12.