anth g6085

pocket things

katie skaggs (columbia university)

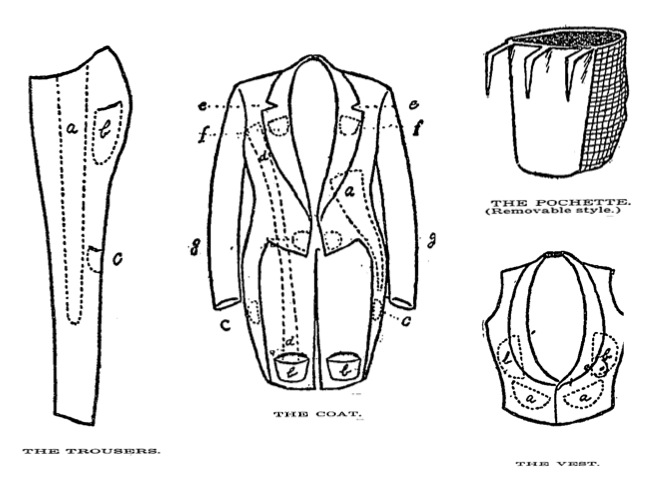

Defined primarily by their functionality as special containers for transport and storage, those common and quotidian objects- pockets- are catalogued according to a vast typology: breast-pockets, inner pockets, coin pockets, cargo pockets, hip pockets [1], thigh pockets, 5th pockets, mitten, trouser, jean, jacket, vest, sleeve[2] and waistcoat, even coat-tail[3] pockets.

“People in the stone age and the cave- dwellers had no pockets that there is any record of, nor did anybody in Bible history. Folks had nothing to carry but money, and that was put in a bag. The Romans and Greeks had the same idea- made their statues of Mercury, God of Gain, showing him holding a full bag instead of with bulging pockets. A couple of hip pockets might have been convenient for Jupiter to carry around thunderbolts in, and a little nectar if flat flasks had been invented, but he doesn’t appear to have had them” (August 28, 1899); if “poets have not yet immortalized them in verse, it is not from having failed to make much personal use of them” (March 24, 1879).

ff

hh

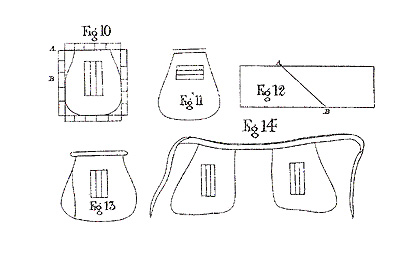

Looking into pocket pre-history, strict Freudians or marsupial zoologists will hardly be surprised to learn that, women were the first to be initiated into the control and secrecy of pockets and their private knowledge- some intricately embroidered, others quite simple and plain- of muslin, silk, linen and cotton- these detachable fragments of the 17th century tied around waists were hidden carefully, buried deeply under the layered depths of women’s skirts and dresses.

Yet far from insignificant these small pouch-like compartments carried around as parts of, appendages of the body flooded the pages of newsprint as matters of great concern; were the Berliner keys of turn of the century defining social, sexual, and class divisions.[4]

While pockets proliferated within women’s garments in the 1700s, by the 1800s women had somehow lost ground in pocket-race while tailors honeycombed men’s suits, pants and overcoats with dozens. Pockets belonged to the labour force; the gentry so well known in popular film imagery for miniature cigar, monocle and watch pockets preferred the luxury of human servants as containers to tote their valuables. A revival, a pocket renaissance, only came with the advent of industrial capitalism and the subsequent rise of the middle class. These new white collars, united with those passionate individuals all ages, classes and genders combined to form of a new pocket proletariat in a worldwide demand for more pockets.

Women, with little rights to private space or property, argued for a more democratic proliferation of pockets among the sexes- “Nature seems to have designed her to blossom into innumerable pockets” one article argued. In the concealed pockets she might carry useful household items, items including a thimble, pincushion, knitting needles, yarn, smelling salts, spectacles, pencil, knife, and pair of scissors, small amounts of money, berries gathered, small sandwiches or groceries purchased at the market, even “a week’s supply of clothing and hairpins, and the visible pockets might be put to uses of which the masculine pocket is totally incapable.” For example, it was suggested, in all earnestness, that womanly pockets might be ideal for carrying a “moderately sized infant” with an additional rear pocket for twins so that a most perfect equilibrium[5] might be obtained (June 10, 1880).

hh

gg

hh

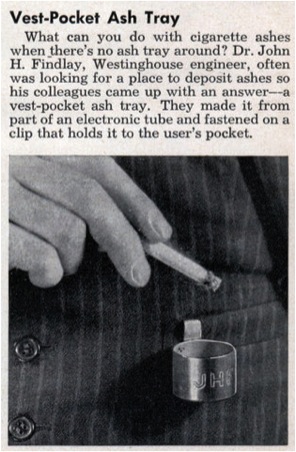

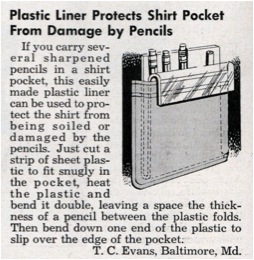

Pockets are animated in their function, “gathering itself for the act of containing” (Heidegger 2001) they are defined in this fullness- a filling of the empty voids. As Heidegger’s jug where “The emptiness, the void, is what does the vessel’s holding. The empty space, this nothing of the jug, is what the jug is as a holding vessel” so the pocket as container holds and fills its hollow spaces. Indeed, they are most often found brimming “quite full of use, of memories, of instructions” (Latour 2000: 10); sometimes bursting at the seams with archival and extended junk of personhood: lint, ticket-stubs, subway cards, keys, business cards, pencils, pens, kite strings, shoe strings, top-strings, handkerchief, tobacco, buckskin gloves, pillbox, mustache comb, revolver, flask, funny jokes clipped from papers, documents—a pocket collection of curios, a museum mass of treasures. Indeed, things wouldn’t be quite the same without those boot pockets stuffed full of prohibited liqueur.[6]

Take the marvels of an adolescent boy’s pockets, those newly initiated and coming of age spaces: “Knife, nails, wire, tweezers, schedule of the big league ball games, grimy foreign stamps and the little flaps for pasting them…loose buttons, plug tobacco, cigar bands…bolts and nuts, piece of candy covered in fuzz, two nails covered in chewing gum” (May 24, 1908), “fishing worms, sections of partially masticated chewing gum…he puts everything in his pockets but his money. That is in coin and he carries it in his mouth and usually swallows it” (August 28, 1899).“Tomorrow it will be the collecting the tops of sardine cans or keeping bottles of alcohol with preserved bugs in them, or there may be a fad which will make it imperative on each boy to have at least one live little turtle or a white mouse in his pocket. Heaven forbid that it take the form of live snakes” (May 24, 1908). One article even catalogues 116 objects that slowly emerge from a single school-boy’s pockets: “Marbles, tin whistle, one shoelace, a broken watch, one fishhook, one mirror (broken), one good mirror, one wooden axe…two buttons, thirty seven stones, three pieces of orange peel…three corks, one pencil, two matches, one key half a cigarette, one punched penny, one locket, two raisins, one broken comb, a cuff pin and a piece of candy” (December 9, 1906). Other marvels: “dead snakes, live snakes, toads, miniature dynamite bombs, electric batteries, worms, caterpillars, tarantulas, centipedes, paste that flames up when you wet it, wasps (stingers removed), riffle bullets (hammered to see if they would do anything), chemicals to make explosive torpedoes, fish roe, face powder and puffs (in sneering sarcasm), false teeth, bottles with angry bees inside and hairs taken from horse’s tail put in a bottle to see if they really turn into snakes” (December 9, 1906).

As extended and distributed boundaries of personhood beyond the skin, pockets serve as archeological blackboxes gathering those “dispersed category of material objects, traces, and leavings…” (Gell 1998: 222) into an accumulated set, a rich pocket of revealing material.

jh

jjjjjjj

jjjjjjj

hh

It is telling that with the first murmurs of a crime, these small pouches are the first items to come under the close scrutiny of investigations “Somebody is holding something back. There is more to learn and we intend to learn it.” It is not hard to imagine the immediate outcome of the situation suggested in a 1903 LATimes headline: “Wifey Finds Photo Hidden in Hubby’s Pocket” or to recreate the crime scene suggested with a pocket full of “three pocketbooks, silver jewels, four silver spoons, three silver napkin rings...two candles, a box of matches, a small jimmy and a bunch of skeleton keys” (September 4, 1900). The pocket holds all of the incriminating traces. One can refuse their identity, address, whereabouts or even knowledge of each pockets contents, but anyone having glimpsed even a short segment of COPS knows this is an argument, hardly rare or unique, that will not go very far. Pockets do not lie- as an extension of the self they are emptied as hard evidence of guilt- difficult, almost impossible to refute.

Yet pockets are as distinguished in what they hold as they are in what they conceal from the eye: Anyone who has seen The Great Escape and anxiously observed as Steve McQueen (or his French predecessor Jean Gabin) carefully mediated their escape through the use of hidden pocket contraptions- (two sacks down each trouser leg operating a string from each pocket which would activate a hole at the bottom from which the sand trickled out slowly dispersing 130 tons of sand from underground tunnels)- knows that an innocent and unassuming pocket can be a matter of great significance. Inaccessible and generally hidden objects “pockets were sometimes the only private, safe place for small personal possessions;” more often than not these significant and secluded interiors remain exclusively elusive, carefully guarded and protected.

To talk of pockets then is to already talk of that seedy, secret, subterranean underworld: This is not to group pockets with those stiff and stale, those poor and boringly unproblematic, unused objects buried “under the ground, unknown, thrown away, subjected, covered, ignored, invisible… ” (Latour 2000: 11) but rather to say that “…the currently accessible things do not tell the whole story about it” (Harman 2005: 17). Any attempt to unmask its secrets to get at its interior only increases the mystery and secrecy- “compounds and magnifies this power infinitely and awakens our desire to see exactly what it is it cannot show” (Mitchell 1996: 78). Bulging pockets, the hidden presence of a concealed object buried within the its depths becomes less the tarty subject of a risqué Mae West quip but a real threat- a thing of danger and terror. Containing odd and mysterious forms, the pocket draws a visceral response; “disrupts and unsettles rather than clarifies” (Pels 1998: 92). Pockets become objects of desire, intrigue, even idolatry – invoking what Fanon calls corporeal malediction, the immediacy of the visual encounter (Mitchell 1996: 74); Revealing the dangerous presence of something hidden deep within its crevices, the pocket exudes a certain carnal seductive character.

The allure of pockets, their hidden contents, is all the more significant, all the more intensely felt for thieves, pickpockets, cut- purses those artful dodgers initiated in secret language and artful actions of the vagabond alleyways. Locating the precise placement of the pocket, assessing its contents, knowing just how to get at the thing while remaining un-noticed, undetected can be a high stakes and terrifying art- a conjurer’s magic.

For Jean Genet prominent and controversial French poet and petty criminal, pockets make the person. “I had decided to be what crime made of me... I was a thief. I will be a thief” (Genet in Sartre 1963: 50). Abandoned, “torn and tattered jacket, pockets ripped, hung down- and a shirt stiff with dirt” (Genet 1964: 18), it is partially due to what his pockets did not have, their unfulfilled function, that propelled him into the actions and life of a thief.

For him the pocket becomes a risky thing of desire that creates an eddying and nervousness within— “Each thing, each object, was the result of a miracle, the accomplishing of which filled him with wonder” (Genet (1943) 1964: 164)[7]. In Thief’s Journal, he describes the actions of a theft accomplished only with the precision of a ritual act: “It will really be performed in the heart of darkness… the walking on tiptoe, the silence, the invisibility which we need even in broad daylight, the groping hands organizing…gestures of an unwonted complexity and weariness… requires a host of movements, each as brilliant as the facet of a jewel. When I discover gold, it seems to me like I have unearthed it; I have ransacked continents, south sea islands…”(Genet 1964: 29). The author becomes excited, captivated with the possibility of coming into contact with both the phenonomenal surface and veiled underground of the thing, a burglary that would also simultaneously link the object and subject “transformed into a bomb of what seems to me terrific power imparts to the act of gravity, a terminal oneness” (Genet 1964: 30). It is a risk where even the slightest mistake could cause him lose everything.

“Bliss and terror are twinned aspects of an object's departure from its ordinary place” (Plotz 1998). In the same way, pockets usually demand our attention and only became significant and dangerous[8] - a matter of great concern- when they recede from us: when lost, stolen, confiscated, pocketed, laid bare and empty. “The object has been pocketed only to be revealed by its absence[9]” (Stewart 1980: 1128) In a raid, Gent’s own pockets were searched and the carefully concealed, astonishingly discreet objects contained within were emptied and seized, laid bare on an examining table – a momentary encounter that becomes a painfully haunting event throughout his journal. Confronted with an empty pocket, a trace, there is a frenzied attempt at a re-creating that moment of loss, the mind creates phantoms replicas to replace the original object retraces the genealogy, a timeline of steps carefully tracking its movements and actions- and yet the thing stubbornly withdraws from human access- remains a frozen object of museum display, a brief newspaper description or filed away lines of a police report.

Even what the pocket contains was bound to escape us. “As they circulate through our lives, we look through objects (to see what they disclose about history, society, nature or culture-above all what they disclose about us), but we only catch a glimpse of things” (Brown 2001:4). “The thingness of the thing remains concealed forgotten. The nature of the thing never comes to light, it never gets a hearing” (Heidegger 2001). Yet while pockets, as all things, withdraw from human access this is not to deny the impact and allure of their elements; “we under go concrete sensual experiences anyway” (Harman 2005: 147).

gg

references

Brown, Bill. 2001. “Thing theory.” Critical Inquiry 28(1): 1-22.

Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. New York: Clarendon Press.

Genet, Jean. 1964. The Thief’s Journal. New York: Grove Press, Inc.

Genet, Jean. (1943) 1964. Our Lady of the Flowers. New York: Bantam.

Harman, Graham. 2005. Guerrilla Metaphysics. Chicago: Open Court.

Heidegger, Martin. 2001. “The thing.” In Poetry, Language, and Thought, pp.165- 182. Harper Collins, New York.

LA Times. 1903. “Wifey Finds Photo Hidden in Hubby’s Pocket.”

Latour, Bruno. 2000. “The Berlin key or how to do words with things.” In Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture, pp. 10-21. Routledge, New York.

Mitchell, W. J. Thomas. 1996. “What Do Pictures Really Want?” October 77: 71-82.

New York Times. May 24, 1908. “A Peek Into A Boy’s Pocket: Styles and Fashions in Junk Change as Rapidly as Women’s Headgear”

New York Times. December 9, 1906. “Wonders of a Boy’s Pockets”

New York Times. March 22, 1903. “Women and Pocket Equilibrium.”

New York Times. September 4, 1900. “Thief Caught With Booty: Boys Noticed Bulging Pockets and Followed Him, Cause His Arrest, and the Police Think They Have Made An Important Capture”

New York Times. August 28, 1899. “World’s Use of Pockets: Men’s Clothes Full of Them While Women Have Few; Civilization Demands Them; A Tailor Tells the Queer Purposes Pockets are Made By Some Men to Fulfill.”

New York Times. June 10, 1880. “A New Agitation”

New York Times. March 24, 1879. “Use of Trouser Pockets. The Custom of Stowing the Hands There-In: Moral and Aesthetic Considerations Thereto Appertaining.”

New York Times. April 13, 1896 “Must Have Been Her Own Pocket: Sympathy for the Young Woman Who Was Strangely Paralyzed.”

Pels, Peter. 1998. “The spirit of matter: on fetish, rarity, fact and fancy” In Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces, pp. 91-121. Routledge, New York

Plotz, John. 1998. “Objects of abjection: the animation of difference in Jean Genet's novels.” Twentieth Century Literature.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1963. Saint Genet. New York: George Braziller, Inc.

Stewart, Susan. 1980. “The Pickpocket: A Study in Tradition and Allusion.” MLN 95 (5): 1127-1154.

works consulted

http://www.vads.ahds.ac.uk/collections/pocketsofhistory.html

http://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/fashion/pockets/index.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/pda/A798159

New York Times. March 20, 1904. “Some Secrets of the Art of the Conjurer: Developments in Dress Have Made Possible Many of the More Modern Tricks.”

New York Times. November 14, 1897. “Women’s Pockets.”

New York Times. March 11, 1880. “Losers of Pocketbooks: The Work of Bad Pockets and Nimble Thieves.”

[1] “Police men have a long case, or scabbard, sewed inside the right hand hip pocket to hold their baton. Comparatively few men carry revolvers, but nearly all our orders for trousers call for two hip pockets” (August 28, 1899).

[2] “Now and then we have an order for an overcoat with a pocket in the left sleeve. We always know the man who gives that order is in love with his wife or someone else, for the purpose of the pocket is to let a woman holding the man’s arm slip her hand into it” (August 28, 1899).

[3] “You can’t carry anything in them that you can’t afford to sit on, and even a handkerchief there gives a hanging bustle effect” (August 28, 1899).

[4] If I site this socio-historical genealogy of pockets it is perhaps only to lament the current pocket apocalypse: that has seen the decline of the less known or extinct specimens of watch, fob and ticket pockets- a loss coinciding with the dwindling appearance of those old whistling dandies and flaneurs jingling the pocket-change within convenient crevices. Durable objects traded in for a proliferation of conversation on those boroughs of voters and spaces of taxpayer billfolds (pocketbooks).

[5] “Pocket equilibrium, sir, is that happy adjustment of the articles in his pockets by which a man maintains his balance an keeps himself from becoming lop-sided or toppling over” (March 22, 1903)

[6] “In South Carolina and parts of Georgia where there are dispensary laws tin cans are made to fit in overcoat pockets with rubber tubes and little faucets run through the lining inside and liquor is drawn from them by the drink” (August 28, 1899)

[7] “Riddled with numerous interior objects that hypnotize me, that absorb my attention as I enjoy their seamless facades and aim my attention at the objects lurking beneath them” (Harman 2005: 30).

[8] An 1896- a story ran in the Times of the real danger of pockets- a young woman’s hand was strangely and suddenly paralyzed upon reaching into the depths of her coat pocket (it was, not her husbands, the paper surmised, as “it is only after a longer period of holy wedlock that a woman investigates her husband’s pockets”).

[9] Presence of an absence: “With the gesture of a pickpocket, there is no after the fact since the evidence, the object of desire and consumption has disappeared” (Stewart 1980: 1128)

hh