anth g6085

the vw camper

maxime de turckheim (columbia university)

When considering this question we are faced with a multitude of solutions across a multi disciplinary specter, none of which really seem to provide us with a satisfactorily answer. Appadurai’s tackling of this problem in The social life of things though convincing, ends up perceiving objects as empty vessel whose meaning is created by moving them through the human, social world. This is an approach I wish to avoid since it attributes agency solely to human actants. Pinney on the other hand, approaches this problem from a different angle, viewing objects and things as existing as mere fractions of themselves in a specific space and time. This is a concept that I find highly appealing yet there is weakness to it as Miller rightfully points; it is easily applied to unique and spectacular objects but when applied to those “mundane things that inhabit our everyday lives but which we fail to acknowledge”, it falls short. But this notion of semi-object semi subject existing and constituting itself constantly temporarily draws us far away from the object orientated approach developed by archeologists.

It appears to me highly unlikely that we are the first society to be constantly renegotiating our relationship to the objects and things that co-inhabited our environment. Heidegger asks us what the jugness of a jug is? Or when is a jug jugging? From my perspective the thingness or a thing materializes itself before our eyes every time we are forced to co-exist in the same space. And that thingness is never a constant given. Just like humans, objects can be unpredictable and can surprise us. This especially becomes evident in times of crisis where the thingness of a thing can become one of many things. The smoker who has just realized that he does not have an ashtray will look at a can of Coca Cola and thing “Hey, this is now an ashtray!” This is where Latour becomes very handy in explaining these hybrids in the form of networks.

kj

kj

I am an avid supporter of the belief that subjects are made up by the objects that surround them. However I also maintain that agency is potent from both of these entities for the length of the relationship they hold. This is where my interest lies with things that pass through time and space and become new things. What was a brand new fashionable designer sweater bought by an individual in 1983, will be rediscovered as a vintage sweater in a thrift store in 2007 establishing a entirely new relationship with the material world around it. Baudrillard maintains that when an object is owned the person who owns it somehow takes on the object’s status. An antique cupboard will always trump an Ikea cupboard due to the fact that it signifies higher social status and implies heritage. The problem with Baudrillard’s approach is that objects are fixed and always come to signify one thing only. If a network were to be set up between an object and a subject, the subject would be the only one prone to variation. What would constitute a network between involving my vintage sweater and I may vary hugely depending on where I am.

I have always been interested in objects held strong cultural significances that from one day to the next went underground, disappeared, only to re-emerge at a later date with a completely new significance. How does time impact on an object and the networks it constitutes is a question I wish to explore through the analysis the Volkswagen camper van.

In order to fully understand what a camper van it is necessary to draw up a historical account of its existence. The origin of the camper van can be traced back to 1929 Detroit, Michigan to the credit of Arthur G. Sherman. Sherman originally created a tented box on wheels that could be towed behind a car and where individuals would be able to sleep. It had bunk beds and a coal oven stove and was 9 feet long and 6 feet wide. This unit was so successful that Sherman decided to start manufacturing them in bulk. At this point however the trailer manufacturing industries and the automobile industries remained distinctly separate.

It was only a result of WWII that actual camper vans could be conceived. Due to housing shortages in the USA during this period, the government was obliged to find alternatives to this problem and invested heavily in the trailer industry. As a result huge improvements were made to these, and many of the new materials developed as a result of the war years could be incorporated into its design.

Heavily influenced by what was going on in the USA, Volkswagen decided to create it’s own version of a trailer that would become known as the campervan. It was in fact adapted from a previously existing automobile model called the VW Transporter (that was presented to the world on the 12th of November 1949) originally conceived as a delivery van. Volkswagen decided to license other companies to convert this model into campers, the most famous collaboration being with an English company called Westfalia Coachworks.

The success of the camper van in Europe was largely due to the social context of the time. The war had left people impoverished and in need of a vehicle that could double as a second home. Beds and cookers were part of the initial fixtures of the Camper Van allowing people a basic level of comfort. The popularity of this type of transport became further enhanced by the publication of a book called South Africa Today: A Travel Book by Erna and Helmut Blench who had purchased one of the prototypes of the camper at the Frankfurt Motor show and had traveled in it across South Africa. This demonstrated the accessibly of places that the vehicle allowed finally leading to the development and release of the Devon Camper in 1957, fully fitted with all the amenities.

Already if we were to consider the camper van as an object in the 1960’s we would have to deduce that it was extremely multi sited. Not one person, social situation or material can be credited with bringing it into being and it is in itself a bundle of phenomena that has developed through time and space. In considering the camper as just coming off the factory floor, we are already faced with a multitude of different angles to approach and understand it by. As much as I would find it interesting to dwell on this point longer, I am more interested in the relationships that the Volkswagen camper was able to instigate and forge as it joined the material world.

When I think of a camper van, I can never quite picture it as a static thing. Sometimes I see it as being red, sometimes green, I often fantasize about all the possibilities for the interior and do not even begin to conceive what the engine is like. As Simmel famously stated, coming closer to things only shows you how far they are from us. But I would like to begin with analyzing the way a subject would experience such an object: as a commodity ready to be possessed.

When I talk about camper vans as sites, I would like to draw a reference to Latour and his notion of reality consisting entirely of hybrids. This is quite obvious in the case of the camper due to the fact that a camper once it is becomes possessed by an individual is so imprinted with him that we can not consider it as a entity solely belonging to the material world of the inanimate. The material form of the camper van is in itself inviting and inevitably has a strong impact on both the material world that it inhabits (its’ occupation of space) and the person who has the strongest relationship with it. It invites and is invited. When a standardized camper van is brought into the world, it becomes a commodity, alienated from the human world. It is unrecognizable to him and as a result allows him to objectify himself onto it (Miller). The act of objectification is of central importance to the relationship held by object since it allows a conceptualization of the thing that presents itself to you, which in itself gives it form and creates a consciousness of it.

dd

When reading a variety of narratives by individuals who have as a possession a campervan, it becomes clear that in each instance, the camper as a commodity becomes a lot more than the fetishized impersonal view that Marx establishes of these. In many cases for the length of the relationship between the van and the subject, there is a sense of fondness directed towards it. It is a vessel that allows individuals to express themselves and establish social relations between themselves. “Social relations exist in and through our material world that acts in unexpected ways that cannot be traced back to some clear sense of will or intention” (Miller). Miller regards the encounter between two separate entities as a mutually constituted one, whereby the act of objectification merges the two together. The alienated form with which the van presents itself to us, allows us to enter into a relationship with it, charging it with meaning and significance. In the case of the VW camper, individuals have been able to do this mainly through customizing what was an impersonal uniform commodity. This is a brief account a couple’s encounter and experience with the camper:

“The camper was a Canterbury Pitt conversion, painted red and grey. We called here Momo after the character in Michael End’s novel The Grey Gentleman. Momo fights the stealers of time who are turning people into a world of materialistic clones; somehow it seemed fitting”

By simply giving the object a name, we are already differentiating it from all the other objects that surround it. In the case of the couple above, David and Cee Eccles, the name Momo was painted on the van to truly differentiate it from others in a way anthromorphising it.

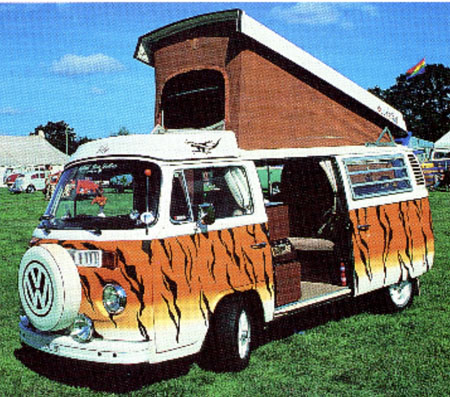

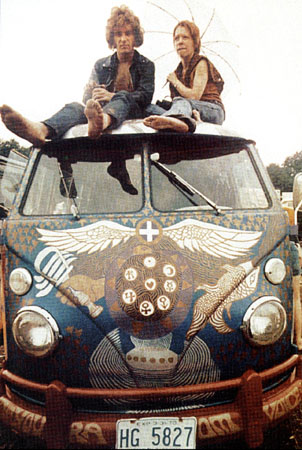

But is it really realistic to view the relationship between a camper van and it’s owner in such straightforward terms? From where does the agency emerge that allows for these two entities to co-exist together as a phenomenon? Alfred Gell establishes a theory that distributes agency through a multitude of actors (both human and non-human). He sees the act of creating as a means for an individual to extend himself into the world and see objects as the vessel by which agency can be abducted and distributed to other individuals. But it becomes problematic to understand where agency is coming from when it is being applied to an object by a multitude of sources. In the case of the camper van who should be credited with the agency that it distributes? Can the patients not have the power to project their own agency onto an object and thus change its significance? How about widely distributed and abstract abduction of a Volkswagen’s agency? The van was adopted as a representation of a whole social movement in the 1970’s and was heavily embedded with social symbolism. And if we consider its position today it is seen as a collectible that draws individuals together, through festivals (Vanfest) and mutual appreciation groups. Could these larger movements not be able in return to alter the agency that the agent has embedded upon the van? In a way it is necessary to consider the VW camper van on a two fold basis: on the one hand as the private property of an individual that joins two entities into a network, and on the other hand as meta-symbol (Miller; 1998) that allows it to be view not as an icon for a specific reference, but instead as evoking a higher are more mystic mode of symbolization.

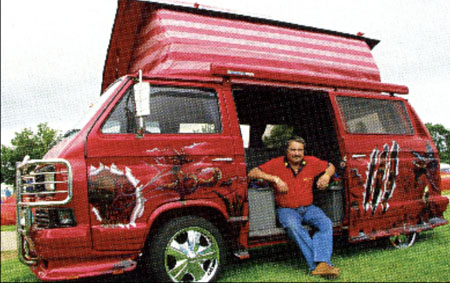

Considering the former, in many instances the camper comes to be forgotten and abandoned, only to be rediscovered and repossessed. A huge amount of resources are poured into it in order to make it a reflection of the person who owns it. This in a way changes what it symbolizes. The Red Devil below can be seen to abduct the viewer into a relationship with the owner, allowing the agency of the later to be distributed to the former. I do not wish however to claim that agency is only dispelled by the subject through the object. The VW Camper in itself exerts agency, as a symbol, sign and phenomenon. It is instantly recognizable and due to it’s symbolic importance and ability to signify a variety of different trends, events and experiences, exerts in itself agency without the need of a human intermediately. Just through its materiality, it has agency over the subject who wishes to exert agency over it. It has long panels that allow elaborate decorations, a specifically shaped interior, forcing an individual to work around it. As Bill Brown has noted, when we are presented with the camper and it’s owner, we are systematically presented with a phenomena that exists here and now. A collaboration between two entities in order to produce a subject-object, object-subject type of thing.

gg

hh

I would like to use the Latourian notion of actor network theory (ANT) in order to explain the phenomena of the VW camper in itself. Considering the camper van-human hybrid, we are able to see that semiotic and material networks are continuously performed and generate different ends depending on time and place. Conflicts may arise when a network is interrupted (owner losing interest in the van or being forced to sell it) creating a whole new set of networks and relations. Agency in this term is neither attributed to the human (owner) or non-human (camper) but instead in the association between the two. For a VW Camper to be what it is thus, the presence of a subject is necessary to enter into this relationship. What is a camper thus if there is no human to claim it as such?

The ANT is useful in understanding the constant renewal of the VW campers’ image throughout history. The network that existed between individual A and the van, who used the van for vacations and individual B and then van 10 years later, who used it to tour with his band is completely different and in a way unique and separate from one another. Though the VW Camper is a material presence, it in a way becomes so abstract that we are only able to identify what it is when we observe it in a network. Thus any archeologist, who was to excavate a camper van in the far away future, would be opening up a new network completely separate and distinct from any previous one that existed. The power which I would like to attribute to the VW camper is it’s ability to reproduce itself and adapt to a variety of settings and situations allowing it’s survival.

ff

ff

What is complicated when addressing the materiality of a VW camper van is the complexity of the networks that constitute it as a phenomenon? On the abstract level of the concept of a camper, we have a network linking large institutions and ideas such as the multinational company Volkswagen, to hippy movement, to the concept of family and freedom. However the camper is localized in an ethnographic account, we get a different set of networks that develop: that between a variety of actants, both human and non-human. The bundles of relations and things, both macro and micro, are expressed in one site as one phenomenon, that in turn are constantly being renegociated as they pass through space and time.

dfd

ff

references

Appadurai, Arjun. 1986.The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Pp. 3-63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baudrillard, Jean. 2005 [1968]. The System of Objects. Verso, New York.

Eccles, David and Cee, 2006. Campervan crazy. Kyle Cathie Limited.

Latour, B. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Miller, Daniel, 1998. Material Cultures. Why some things matter. University of Chicago Press.

Miller, Daniel, 2005. Materiality. Duke University Press.

Pinney, Christopher, 2005. Materiality. Duke University Press.

Gell, A. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Clarendon Press, New York.