anth g6085

the ghost dance garments

megan osborn (columbia university)

A Barracks Ballad by Private W.H. Prather, member of the 9th Cavalry at the Battle of Wounded Knee, 1890

The Red Skins left their Agency, the Soldiers left their Post,

All on the strength of an Indian tale about Messiah's ghost

Got up by savage chieftains to lead their tribes astray;

But Uncle Sam wouldn't have it so, for he ain't built that way.

They swore that this Messiah came to them in visions sleep,

And promised to restore their game and Buffalos a heap,

So they must start a big ghost dance, then all would join their land,

And may be so we lead the way into the great Bad Land.

They claimed the shirt Messiah gave, no bullet could go through,

But when the Soldiers fired at them they saw this was not true.

The Medicine man supplied them with their great Messiah's grace,

And he, too, pulled his freight and swore the 7th hard to face.

Bjornar Olsen questioned “why has the physical and ‘thingly’ component of our past and present being become forgotten or ignored to such an extent in contemporary social research?” (Olsen 2003: 87). In historical examinations of events, the material “stuff” often takes a back seat or is completely left out of the discussion of a particular event. To fully understand the significance of the Battle of Wounded Knee, one needs to look at the garments the Native Americans wore as they participated in the Ghost Dance and then fled for their lives on that December day in 1890.

The great underlying principle of the Ghost Dance Doctrine is that the time will come when the whole Indian race, living and dead, will be reunited upon a regenerated earth, to live in aboriginal happiness, forever free from death, disease and misery. The white race, being alien and secondary and hardly real will be left behind . . . And cease entirely to exist. (Mooney 1896: 139)

This paper is an analysis of the costumes associated with the Ghost Dance religion, prophesized by the Native American medicine man Wovoka, and practiced by the Lakota Sioux. The garments worn during the Ghost Dance religion’s ritual dances were imbued with the supernatural to protect the dancers. The Ghost Dance Doctrine preached that Native Americans needed to live peacefully with the white settlers and practice the Ghost Dance until a time of reunification with their ancestors in a natural world abundant with wildlife and without the presence of the white settlers and soldiers. The buffalo were a central part of Lakota society as they served to fill their social, religious and material needs. With the arrival of the white settlers and westward expansion, the buffalo were hunted for sport and killed off in great numbers and the Lakota lifestyle was greatly changed.

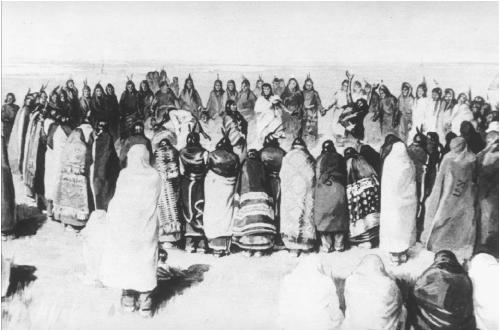

Dances were assembled throughout the plains with thousands of participants dancing and singing for hours on end. The Ghost Dance became a powerful symbol for Native Americans as well as the U.S. government / settlers. While Native Americans were dancing in hopes of a peaceful coming of a new world; the whites believed they were preparing for a final standoff. This tension came to a head with the dancing of the Lakota Sioux. Settlers complained to the government that they feared the Lakota were going to attack their homesteads and requested military intervention.

Their costumes were of white cotton cloth. The women's dress was cut like their ordinary dress, a loose robe with wide, flowing sleeves, painted blue in the neck, in the shape of a three-cornered handkerchief, with moon, stars, birds, etc., interspersed with real feathers, painted on the waists, letting them fall to within 3 inches of the ground, the fringe at the bottom. In the hair, near the crown, a feather was tied.

I noticed an absence of any manner of head ornaments, and, as I knew their vanity and fondness for them, wondered why it was. Upon making inquiries I found they discarded everything they could which was made by white men.

The ghost shirt for the men was made of the same material-shirts and leggings painted in red. Some of the leggings were painted in stripes running up and down, others running around. The shirt was painted blue around the neck, and the whole garment was fantastically sprinkled with figures of birds, bows and arrows, sun, moon, and stars, and everything they saw in nature. Down the outside of the sleeve were rows of feathers tied by the quill ends and left to fly in the breeze, and also a row around the neck and up and down the outside of the leggings. I noticed that a number had stuffed birds, squirrel heads, etc., tied in their long hair. The faces of all were painted red with a black half-moon on the forehead or on one cheek.

-Mrs. Z. A. Parker, description of a Ghost Dance observed on White Clay creek at Pine Ridge reservation, Dakota Territory, June 20, 1890.

The Lakota were emboldened in their dance rituals by the addition of a garment that promised invincibility to the wearer. While many tribes wore similar costumes during the Ghost Dance; the Lakota Sioux were one of the only tribes to believe the costumes could physically protect them (Jenson 1991: 10). The Ghost Dance costumes, with their designs and materials pulled from the natural world, were a rejection of white settlers’ material culture. In an effort to return to the natural state that had existed before the westward expansion of white settlers, the costumes were designed with images of stars and animals.

Each garment was an individual expression. The person wearing the garment would have chosen and painted the symbols onto the cloth or hide themselves. Often, the images painted on the garments were ones seen in visions by the individual. Symmetrical designs on either side of the body were often components of the overall style. The symbols painted on the garments represented specific things. Dots represented harmful hail and by painting these onto the garment one was protected from harmful projectiles. Eagles and other birds of prey were seen as strong and brave figures; the crow was seen as the messenger of the spirit world and could help the wearer escape death. Other important themes include dragon flies which rendered the person wearing the motif invisible and butterflies which made one light and agile in battle.

Painting the symbols, seen during “visions”, was a visual pact with the supernatural. By drawing these, it was believed the supernatural would protect and assist in whatever goal the individual sought to meet. For Ghost Dancers, this was physical protection and a return to ancestral times. The pact with the supernatural placed magical properties on these shirts and bullets or any sort of weapons could not go through them. The dancers, by wearing these shirts, believing that if a white settler or soldier tried to stop them, they would be safe. A closer examination of the reliance and relationship with the supernatural and the protection of the garments lead us to consider the garment as religious fetish (Ellen 1988: 219). While the garments were not objects made in the likeness of humans, the garment can be regarded as an active agent. Indeed, there seems to be an uncertainty with these objects as to whether the garments themselves effect changes or if it is the supernatural that does so (Ellen 1988: 215). Since the individual wearing the garment designed it as a visual pact with the supernatural, the shirts were the physically impenetrable object and the supernatural was beholden to the garment’s images to protect the individual wearing them. Thus, the Ghost Dance shirts and dresses had their own agency and controlled the actions of those wearing them. The shirts became active agents in the Ghost Dance religion as the Lakota Sioux were dependent on them for their magical protection should the need arise. As military altercations with the U.S. troops had failed, the Lakota Sioux were reliant on the assumed power of the shirts.

Indeed, the Ghost Dance garments provided a protective skin for the dance participants (Gell 1993: 3). By wrapping the body in images of nature, the garment provided another layer of skin for those wearing them. The images of nature as seen in visions referenced the return to ancestral times when animals were abundant. The garments thus offered protection from the dangers and uncertainty of the current time. The clothing itself influenced the intentions and actions of the dancers. Wearing the Ghost Dance shirts and dresses visually altered the body and the way the individual perceived themselves and their social interactions and allowed for the empowerment of the community as a whole. The garments gave the individual and the community a sense of purpose and protection to effect change. In ways, the Ghost Dance costumes were examples of layering and an extension of the human wearing them (Knappett 2006). The costumes were often paired with face and body painting as additional layers of protection. As a Lakota Sioux leader, Short Bull, told concerned Ghost Dance participants:

If soldiers surround you four deep, three of you, on whom I have put holy shirts, will sing a song, which I have taught you, around them, when some of them will drop dead. Then the rest will start to run, but their horses will sink into the earth. (Mooney 1896: 151)

The garments created a boundary between the body and the world beyond and also functioned as support for the expression of social relations (Gell 1993: 24). The images on the Ghost Dance garments indexed the causal factors that produced them, namely the turn towards nature after the altercations and change of lifestyle due to the U.S. government. Thus the garments became a symbolic indicator of the events, relationships and obligations on the individual (Gell 1993: 36-7). The shirts created social order by providing a framework in which the Lakota Sioux could work towards the coming of the ancestors and nature.

Furthermore, the garments provided a new “things-centered form of sociality” (Preda 1999: 349). In a time of turmoil within the community, the garments, through their own social power, provided stability and new avenues for furthering a social order focused on the natural world. The westward expansion of the white settlers had led to the dwindling of buffalo herds in the region. The forced settlement on reservations also changed a once nomadic form of life. For the Lakota, these were central to the tribe’s social relations. Hunting, arts and materials associated with this lifestyle were socially significant and lost when the buffalo disappeared and they were forced onto the reservations. The garments gave direction and were a way to try to restore a past order and return to traditions lost.

In December of 1890, after being pursued by the United States military throughout the region, close to three thousand Lakota Sioux gathered at Wounded Knee. The soldiers proceeded to enter all the tents at the camp and collect what weapons the group had. Many Lakota were distressed by this invasion and one began to rally the group against this interference. He began “telling them that the soldiers would become weak and powerless and that the bullets would be unavailing against the sacred ghost shirts” (Mooney 1896: 231). Some began singing Ghost Dance songs and one stooped to pick up some dirt to throw in the air as a signal of the start of the dance. The military interpreted this as a signal to begin fighting and seconds later a gun was fired and the massacre had begun (Jenson 1991: 18). Many died within the first few minutes of the fighting. Realizing that their shirts were not protecting them and that the Ghost Dance songs were not effective against the U.S. military; some Lakota fought with what weapons they could find while others ran for their lives; many died.

It is important also to explore the relationship between the garments and the U.S. troops. Despite the removal of the weapons, the soldiers were still fearful that the dance and the invisibility provided by the costumes promised impending war. As Webb Keane argues, “the fetish remains a temptation even to those whose knowledge would deny the existence of that which they desire . . . it may have to do with the way in which other people’s illusions threaten the very autonomy of the subject” (Keane 1998: 14). While it may be argued that the Lakota view the garments as fetishes with great power, this identification also influences the U.S. troops interactions with the supernatural power of the costumes. The patterned garments drew the troops’ gaze where a plain garment may not have done so (Gell 1993: 36). In this way, the garments mediated the relationship between the two opposing groups. The U.S. troops came with background assumptions on what the clothing and its images meant and how they functioned within the Native American context (Keane 2005: 191). The elaborately designed garments, rumored to protect the dancers from any harm and the dancers’ sudden movements were interpreted by the U.S. troops as a sign that the Lakota Sioux were going to fight. The garments, unique to the Lakota, presented the possibility for the unknown for the American troops. The clothing determined the expectations and consequent actions of the U.S. troops because it determined how the Lakota Sioux were going to act (Miller 2005: 5). Therefore, the Ghost Dance garments influenced the actions of both the Lakota Sioux and the U.S. troops.

Despite being stripped of their weapons, the Lakota began to perform the dance designed to rid the land of the white settlers and troops. At the time, it was the only recourse they had to the invasion of their land. The shirts emboldened them to dance and, thus, influenced their behavior. The troops felt the significance of hundreds; even thousands of participants dancing wearing these garments presenting a massive, unified performance. The dancers, influenced by the garments and their protection, fully engaged in the dance. Thus began the fighting that would involve the deaths of many Lakota.

An examination of the Battle of Wounded Knee would not be complete without an examination of the garments and the relationships they created between the opposing parties. Each group’s understandings and preoccupations with the garments influenced their behaviors and contributed to the sequence of events. It is notable that the violent encounter of Wounded Knee was not replicated throughout all the tribes that practiced the Ghost Dance. Something impacted this encounter and it was the garments the dancers wore.

works cited

Ellen, R, 1988. “Fetishism” Man 23: 2, 213-235.

Gell, Alfred, 1993. Wrapping in Images. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Jenson, Richard, R. Eli Paul, and John E. Carter, 1991. Eyewitness at Wounded Knee. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Keane, Webb, 1998. “Calvin in the Tropics: Objects and Subjects at the Religious Frontier" Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces. New York and London: Routledge.

Keane, Webb, 2005. “Signs are Not the Garb of Meaning: on the Social Analysis of Material Things.” Materiality. Durham: Duke University Press.

Knappett, Carl, 2006. “Beyond Skin: Layering and Networking in Art and Archaeology.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 16:2, 239-51.

Miller, Daniel, 2005. “Introduction.” Materiality. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mooney, James, 1896. The Ghost Dance Religion and Wounded Knee. New York: Dover Publications Inc.

Olsen, Bjornar, 2003. “Material Culture after Text: Re-Membering Things.” Norwegian Archaeological Review, 36: 2, 87-104.

Preda, Alex, 1999. “The Turn to Things: Arguments for a Sociological Theory of Things.” The Sociological Quarterly, 40: 2, 347-366.

PBS 2007, “Archives of the West, 1887-1914.” http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/resources/archives/eight/