anth g6085

the nutshell studies of unexplained death

rachel gershman (columbia university)

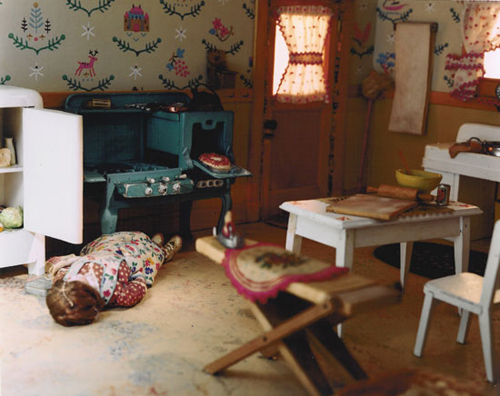

Black stockings painstakingly knitted with straight-pins. A tiny key that locks a miniature door. A little coffee pot complete with mini coffee grounds. These objects might be part of a normal--albeit obsessively designed--dollhouse. Until you notice the carefully-plotted blood splatters on the wall or the perfect reddish tinge on the asphyxiated doll’s skin. A typical dollhouse, this is not.

>>>>>>>

>>>>>>>

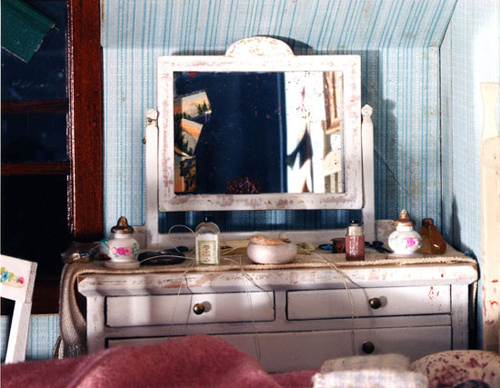

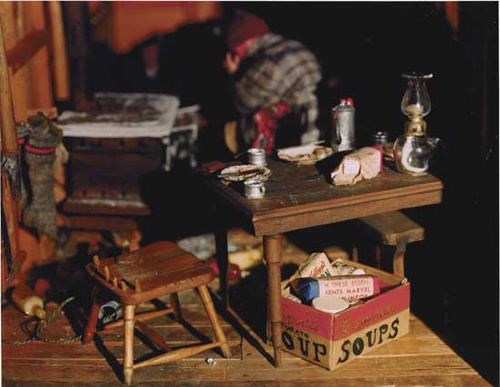

In fact, despite its miniature size, it’s not a dollhouse at all, and the woman who created these pint-sized rooms would balk at the term. The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, created by Frances Glessner Lee in the 1940s to teach police officers about the importance of objects in solving crimes, are 1:12 scale representations of actual crime scenes, complete with dead bodies, fire-damaged walls and blood-stained carpets. Although each of the 19 dioramas is a composite of several criminal cases, rather than an exact copy of one specific crime scene, Lee crafted each with incredible attention to detail to ensure that the policemen viewing them would see them as credible replications of real life. Window shades work, pencils write and doors lock. (Botz, 2004)

Lee’s wealthy family (who lived in what is now the Glessner Museum in Chicago) did not allow her to attend college, but she nevertheless developed a fascination with forensic science and made it her mission to improve criminal investigation, particularly in terms of the role of medical evidence. In her 60s, she became a captain in the New Hampshire State Police, and was the first woman to join the International Association of Police Chiefs. In response to seeing botched cases due to mishandled or unnoticed evidence, she created the Nutshell Studies, naming them after the police saying, “Convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.” First used in Harvard seminars in 1945, they are now located in Maryland, and are still used by officers-in-training, who, then and now, regarded the dioramas as serious education tools. (Botz, 2004)

ddd

The Nutshell Studies were recently given a wider audience through a 2004 book by Corinne May Botz featuring Botz’s photographs of the miniature crime scenes. As the Nutshells have been endowed with new life, both in a literal and figurative sense, through Botz’ photographs, much could be written about the added layer of representation and/or misrepresentation inherent in such images. As photographs capturing moments in time recreated in miniature, the possibilities for discussion are numerous, but will not be discussed here. Instead, I will focus on the objects themselves – both in terms of the complete rooms and the individual items that comprise them.

Taking a cue from Tim Ingold (2007) to consider the actual materials making up the materiality of an object, I will start by discussing Lee’s choice of and interaction with the physical materials that comprise the Nutshells. Her almost obsessive selection and use of these materials in the creation process is key to understanding the objects’ meanings. For example, reflecting her strong devotion to creating objects as “real” as possible, Lee repeatedly wore and re-wore a suit of hers in order to achieve the perfect look of worn-out fabric for one victim’s pants. (Botz, 2004) Many of the items in the Nutshells were handmade, while others were bought, and still others were bought objects repurposed for a use different from their intended purpose – such as the Cracker Jack prize that became a rocking horse toy, or the inhaler that became a fire hydrant. (Botz, 2004)

ddd

ddd

Those objects have now taken on completely different meanings, not only as part of a miniature, rather than life-size, world, but as “evidence” for a violent, criminal act. When that object was first created, this use was never considered. But now, as long as the Nutshells exist, it is the only possible context in which it can be understood. In fact, the same could be said for any of the materials Lee used, from the fabric, to the wood, to the paint – at a previous point in their existence, each of these materials could have been used for an entirely different purpose, and thus would have possessed a completely different set of meanings, depending on the context in which it existed.

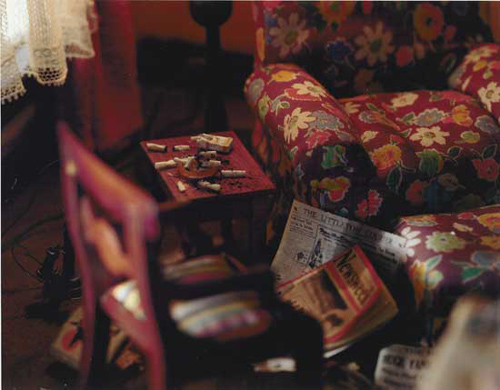

In On Longing, Susan Stewart notes that miniatures, particularly dollhouse scenes, generally allow the viewer to embrace ideas of wealth, nostalgia, the picturesque and an idealized view of some cultural or social “other.” (1993) The Nutshells, however, do not serve this purpose. Lee chose to recreate crimes committed by members of the lower class, and her dioramas clearly reflect the social status of the victims. No opulent Victorian-style furniture fills these rooms, which are often sparse and scuffed. Rather than reflecting the cohesive family life of a dollhouse’s inhabitants, they are predominantly the sites of domestic violence against women, and often include overturned bottles of alcohol. These scenes are not romanticized, pastoral reflections of an other; rather, they suggest the cold, hard reality of lower-class life.

ddd

......

......

ddd

Moving from the specifics of the scenes to develop an understanding of these objects within the larger context of “miniature,” it is worthwhile to consider Douglass Bailey’s theories on miniature objects. He distinguishes between miniatures and models, arguing that models, and not miniatures, are attempts at precise, accurate representation. He suggests that miniaturization necessarily reduces detail; the creator is forced to make a selection about which elements to include. The result is an abstraction of reality that makes demands on the viewer, who must make inferences about the object being represented by the miniature. (Bailey, 2005)

However, I would argue that Bailey’s distinction between models and miniatures is not an entirely useful one. Lee’s Nutshell Studies show how the boundary between the two terms can be blurred. She intended for these scenes to be precise, scale models of reality, certainly not abstractions or generalizations. She was a stickler for ensuring that the scale was correct and the scuff-marks and bloodstains on the floor accurately spaced. (Botz, 2004) Yet, despite her obsessive attention to detail, she could never possibly perfectly recreate reality, and neither can any other scale model, no matter how precise. I would argue that all scale models are miniatures, and therefore will always, inherently lack some aspect of the object being represented. While the intentionality behind models may aspire more toward accurate representation of reality than the intentions behind miniatures, the results of both are ultimately still only representations, and therefore incomplete.

Continuing to define the miniature, I would suggest that the mere fact of considering an object a miniature necessarily entails a comparison to some other object. I would argue that the miniature does not possess its own identity; to be a miniature is to be a representation. The miniature can represent both real and imagined objects, but it still will exist as a reference to something else. That relational process is always present; a miniature is an object that cannot be considered on its own terms.

Some suggest that by preserving a moment or time period, miniatures, particularly dollhouses, create a scene that is, in some ways, dead. (Stewart, 1993) However, since that innate process of viewing the miniature in terms of something else is always present, the object is continually involved in a state of animation. Not only is “miniaturization” a process, but once an object is defined as a “miniature,” it will forever be involved in a process of representation through its relation to some other, larger object. That process serves to activate the object, maintaining its animate nature, regardless of its context or physical immovability.

The miniature takes on this inherent role as a representational object by being intrinsically defined according to its comparison to human scale. Thus, humans generally have the upper hand. (Bailey, 2005) Usually, a miniature empowers its spectator, who has an omniscient view of the scene, as well as assumed or actual physical control over the miniature objects. (Bailey, 2005) Even if, as in the case with the Nutshells, the viewer is not meant to physically touch or move the objects, he has the understanding that he could if given the chance. He possesses an incredible power over these objects and knows that he could destroy this world with a simple brush of the arm. Particularly within the context of the Nutshells, because each object’s location is essential to the overall understanding of the scene, moving objects would diminish, or even erase, their individual and contextual meanings. The viewer’s resulting place of authority, even at an unconscious level, is part of the way he considers the scene.

ddd

.......

.......

ddd

With this authority, the viewer is free to consider a miniature world in a way he would not approach a similar scene in reality. In fact, miniaturization in general allows intimate access to worlds otherwise unavailable to the viewer. (Bailey, 2005) Through the Nutshells, Lee intended for the viewer to closely engage with the objects comprising each room, studying them more thoroughly than might be possible for these training officers in a “real-life” crime scene. She instructs the policemen to imagine themselves as six inches tall, walking around inside the dioramas, considering each object, as they “move” around the room. (cited in Botz, 2004) Each single object within the larger scene presents an opportunity for the viewer to imagine, fantasize and deliberate about its role within this miniature scene, as well as its “real-life” counterpart’s role in the crime.

Also, by moving the viewer from an actual crime scene, with its real dead bodies, gruesome smells and chaotic atmosphere to the more sterile surroundings of the Nutshell representations, Lee created a situation where the viewer is freer to intently study the objects in a safe and controlled environment. In the Nutshells, the viewer is the only one “in” the room, and has open access to anywhere he chooses to look. Nothing will move; no one will be in his way. And, although the scenes are meant to be precise recreations, in the end, the corpse is only a doll, and the blood is fake. This miniature environment is much more manageable for the average police trainee, and presents a means for him to, perhaps, more fully understand a real-life crime scene.

Although Lee wanted the trainees to really engage with the objects, these scenes encourage a highly detached view of a crime scene, and therefore, of the objects inside. Officers are not supposed to look at the blood with an emotional eye, but as a piece of evidence. Similarly, although the results of violence are on view, the assumed violence that led to the frozen moment shown in each scene is a factor only as it relates to solving the crime.

Perhaps Lee was not only training the officers to understand the importance of physical evidence, but also attempting to develop in them a sense of detachment from the objects in a crime scene. Through such detachment, while “seeking only the facts,” the investigator might be able to more objectively and scientifically consider the crime. (as cited in Botz, 2004, p. 47) However, Donna Haraway argues that throughout the history of science and scientific vision, people developed the belief that they possess what she calls “the god trick of seeing everything from nowhere.” (1988, p.581) She argues for “the embodied nature of all vision,” suggesting that “infinite vision is an illusion” and it is impossible to ever have an omniscient, entirely detached view. (581 & 582) Vision of any sort is always tied up with individual positionality and embodied experience. Therefore, Lee’s intention of developing a detached and objective view is perhaps an impossible undertaking.

ddd

ddd

On a basic, physical level, while the viewer can access (at least visually) the Nutshells’ objects in an intimate way, the design of each room and the objects’ locations control what the viewer is actually able to see. He can never have an omniscient view, even though he does have a god-like vantage point over the miniature scene. The objects force the viewer to change his location in an attempt to more fully grasp their meanings, but still, all aspects of a three-dimensional object can never be seen at once. Something will always remain hidden, and the objects will always retain a little bit of mystery. (Bailey, 2005)

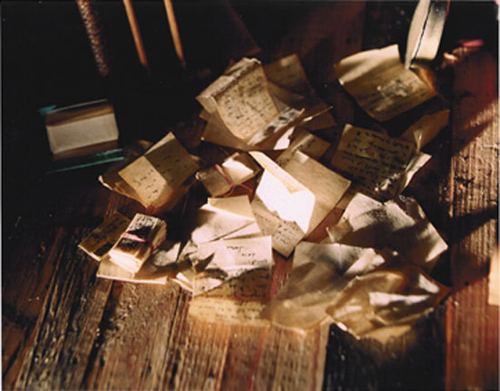

Ultimately, in the Nutshells, it is the objects that reign supreme. An understanding of these objects is wholly dependent on a knowledge of the context in which they were created. And the purpose behind the Nutshell Studies was to highlight the incredible significance of even single, seemingly unimportant objects in solving crimes. That underlying purpose is what endows the objects in the Nutshells with such strong agency. In “Attic,” a woman is found hanging in her attic, but one of her shoes is halfway down the stairs, and her letters are messily tossed across the floor. Could there have been a struggle? In “Unpapered Bedroom,” a lipstick stain is on the underside of a pillow. Could the woman have been smothered? In “Living Room,” the ashtray in an otherwise clean room overflows with cigarette butts. Could someone have recently had company?

As any CSI fan knows, the existence and location of certain objects can be key to solving a crime. And for Lee, the purpose of the Nutshells fully lies in this immense importance of objects. In the world of the Nutshells, as well as in criminal forensics, objects take on a fetishized role because of their potential to contain so much essential meaning. Today, forensic specialists might be able to find answers in a strand of fabric, the position of a gun, the angle of a blood splatter. When Lee created the Nutshell Studies, this was not the case. She felt that too much important evidence was being overlooked, and created these miniatures to help remedy that problem. As she says, “The Nutshells are not presented as crimes to be solved – they are, rather, designed as exercises in observing and evaluating indirect evidence.” (as cited in Botz, 2004, p. 47)

ddd

......

......

......

......

ddd

In her instructions to the officers, Lee writes that they should, upon “entering” a room:

describe the premises in a clockwise direction back to the starting point, thence to the center of the scene, ending with the body and its immediate surroundings. He should look for and record indications of the social and financial status of the people…as well as anything that may illustrate their state of mind up to or at the time of demonstration. …no photographs or fingerprints will be available—the investigator must base his report on the material as represented. (as cited in Botz, 2004, p. 47)

Through these scenes, the officers are meant to appreciate the importance and meaning of individual objects. Perhaps, however, it is easy to pay so much attention to the objects because, as miniatures, they all do look different from their real counterparts. The eye travels over each object individually, more so than if the viewer were in a life-size room. Despite Lee’s commitment to accuracy, miniature objects, as representations of larger objects, contain an element of unfamiliarity and exoticism.

Of course, within a context of intense focus on the objects, the victim’s bodies, too, become another object that requires careful study. Here, the objectified human body carries almost no more weight within the scene than an overturned chair; each requires an analysis of what it might mean within the context of the room and the crime. As discussed earlier, the miniature setting allows for a more detached view of the scene, presenting the opportunity to really view the body in an objectified way, or perhaps preparing the officers to do so in real-life situations. However, at the same time, as Haraway argues, “objectivity turns out to be about particular and specific embodiment and definitely not about the false vision promising transcendence.” (1988, p.582) This bodily objectification can never truly be objective.

ddd

ddd

Despite the objectification of their bodies, the dolls inside the Nutshells reference specific people, adding another layer to their personhoods and memorializing them, in a way, long after their deaths. On the other hand, by changing the names and altering some details, Lee has created artificial representations of these people’s identities (even beyond the obvious artificiality inherent in any miniature recreation). Can these representations, which are so far removed from the reality of their identities, still be considered part of the victims’ distributed personhoods? (Gell, 1998) I would argue that they can, as some element of each person’s identity, however minor or modified, is still retained within Lee’s creations. As the Nutshell Studies index Lee, even after her death, the dolls and their surroundings could be considered an extension of the victims.

When an individual is represented in miniature form, he could be said to have been given a new life in a form that might endure after he is no longer living. By solidifying a particular ephemeral moment or life through materiality, the Nutshell figures do allow the victims to “live on,” in a sense, but paradoxically, in a permanent state of lifelessness. Stewart suggests that one might view all miniature figures as “dead,” due to a doll’s inability to grow or change (1993); but the Nutshell Studies take that idea to the extreme. These figures are both metaphorically and literally dead.

In the end, the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death are full of many material contradictions – both as dioramas and systematic teaching tools. They are simultaneously specific replicas and imaginary fabrications; peculiar combinations of memorials, tombs and morgues; and enshrined, personal domestic spaces and violent sites of destruction.

ddd

works cited

Bailey, Douglass W. (2005). Prehistoric Figurines: Representation and Corporeality in the Neolithic. London, UK: Routledge.

Botz, Corinne May. (2004). The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. New York, NY: The Monacelli Press, Inc.

Gell, Alfred. (1998). Art and Agency. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Haraway, Donna. (1988). “Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective.” Feminist Studies. 14(3), 575-599.

Ingold, Tim. (2007). “Materials against Materiality.” Archaeological Dialogues. 14: 1-16.

Stewart, Susan. (1993). On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

ddd