anth g6085

free toilet

tim gunatilaka (columbia university)

It was one of those restless nights that came to dominate the dragging months of summer, 2001, the summer before my sophomore year. Three friends and I were driving down the suburban streets of Palo Alto. As we passed drab house after drab house, nocturnal eagerness waned, replaced by the sweet thoughts of sleep. Then, it happened—the light. A streetlight, under which, was perhaps the most beautiful yet unexpected sight.

We found a toilet. It was not a particularly special toilet. But it was a toilet nonetheless. Something so ostensibly gross that it is usually quarantined to its own tiny room is now standing out here, unabashedly in the open. But this toilet was clean. At least it appeared to be clean; its porcelain was white and pristine. It was the kind of toilet that I could see myself sitting on, free of shame.

How did this toilet come into being? And who would abandon a perfectly good toilet? Was there something secretly wrong with it? Did the toilet’s former owners know something we did not? Or did they just buy one of those fancy, high tech models, with night-lights and built-in bidets—the kind we see in movies set in the future, or just Japan? [http://images.businessweek.com/ss/06/12/1230_smarttoilet/source/1.htm] We really could not know how it got there. Some of us were even afraid to ask.

Regardless, there it was, shimmering under the subfusc yellow light made brilliant, the toilet resting on some random lawn in northern California. Yet, the toilet was not without adornment. Leaning against the seat—which someone left up, by the way—was a sign, with the word “Free.” The four of us slowly approached the rare form, as if the slightest startle would scare the poor creature away. Yet, we were at a loss as to what to do in this most wondrous situation. Just four hometown pals, separated by college but now reunited, standing around a toilet with a free sign.

What is the essence of toilet-ness? The Oxford Dictionary of English defines toilet as:

1. a large bowl for urinating or defecating into, typically plumbed into a sewage system and with a flushing mechanism; a lavatory: Liz heard the toilet flush | (figurative) my tenure was down the toilet.

• a room, building, or cubicle containing a toilet or toilets.

2. [in sing.] the process of washing oneself, dressing, and attending to one's appearance: her toilet completed, she finally went back downstairs.

• [as modifier] denoting articles used in this process: a bathroom cabinet stocked with toilet articles.

• the cleansing of part of a person's body as a medical procedure.

.dfd..

.dfd.....

Is it the porcelain bowl? The way it flushes? What it flushes? Is it the way it allows a civilized, modernized, and sanitized citizen to complete the most basic of bodily processes? Is it the sense of privacy it affords one, to think, to read, yet still remain connected to the rest of the world, via an unending system of pipes, resting just below our feet? And what about phrases like “potty mouth” and “going down the toilet”? Must there always be such negative connotations?

Can a toilet still be a toilet if it has been dislodged from its social context? Sitting on grass? Or would that make it an outhouse? Perhaps, the smooth, porcelain, white shape before us was actually an artistic statement? [http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/92488.html?mulR=5104] No one knew how to answer these questions nor did anyone dare to guess.

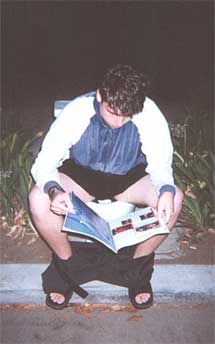

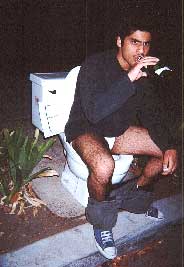

Such uncertainty notwithstanding, another feeling, as if transmitted to us from the toilet, soon emerged. We realized we had to preserve this moment. Thus, there was only one acceptable course of action: find a camera. We got back into the car and raced to the nearest grocery store still open. The urgency was crushing; for we all feared that the more time spent away from the toilet, the more likely someone else would drive by, see the “Free” sign, and take it away from us. Never to be seen again. Each car that passed us on that dark road came to represent competition for our midnight idol. Certainly, other twilight revelers would share in our excitement and not pass up this opportunity. The idea of leaving someone behind to guard the toilet crossed our minds. But for some unspoken reason, we could not break up the group.

After obtaining a disposable camera, we returned to that beloved lawn, not only fearing that someone could have removed our toilet, but even worse, that the toilet was nothing more than figment of our collective imagination. Fortunately, our suspicions were wrong. This beacon of boredom thwarted, this pipeline to friendship, fraternity, and fun was still there.

With the camera, we ensured the permanence of that sublime moment in our young hearts forever. Maybe photography is a poor substitute for remembering, but we had to remember. For in the days of post-adolescent panic and pre-quarter-life crises, nothing seemed more pressing than freezing that instant of both sanctity and silliness. As Bjornar Olsen writes, in “Material culture after text: re-membering things”

People establish ‘quasi-social’ relationships with objects in order to live out in a ‘real’ material form their abstract social relationships. So when we encounter burials, figurines and landscapes—or home decorations—what we are confronted with are really nothing but ourselves and our social relations. Things just ‘stand in for’ and become nothing but a kind of canvas for the social pain we stroke over them to provide a cultural surface of embodied meanings (94).

....dfd..

.dfd.....

If a toilet is indeed a throne, then we all got the chance to play king. We laughed. We cried. We stood. And, of course, we sat. After all, it was a toilet, and that is what you do on a toilet: you sit.

Inevitably, the time came for our departure. Yet, the air was charged with this burning desire shared by all. Do we dare take the toilet? Its sign did proudly proclaim, “Free.” Yet, how could we? How could we take so much out of the toilet and then selfishly refuse to share the revelation with the rest of the world? How could we deny the next group of lost, confused kids wandering the streets in the midnight hour? Moreover, while the sign did say, “Free,” was the toilet really inviting us to take it home? Perhaps the word etched across that sign was really an imperative, commanding us to free our bodies, free our minds, free our selves. Divine wisdom sent from the heavens, by which the everyday becomes singular and the scatological becomes eschatological.

In her 1944 novella “Red Rose and White Rose,” Chinese author Eileen Chang also contemplates a search for solace through the toilet:

Yanli became sick with constipation and had to sit in the bathroom for several hours every day. Only during that time could she justifiably do nothing, say nothing, think nothing. The rest of the time she also said nothing and thought nothing, but then she was still a little anxious and would feel the need to walk about, albeit without a purpose. Only in the bathroom during daylight did she feel secure, rooted. (translated by Rey Chow in “Seminal Dispersal, Fecal Retention, and Related Narrative Matters,” 369)

In the end, I guess it does not matter. Whether it is in the bathroom or on someone's lawn, the toilet still serves its role. As Rey Chow asks, “Should one let go of the shit inside and become liberated, or should one hold onto that shit like a sacred treasure, one that is fiercely guarded by the eye of some mysterious idol?” (370). Such is the power of the toilet—the solitude, security, contemplation, catharsis, and escape. All one can do is sit back and hope for the best.

.dfd..

works cited

Chow, Rey. “Seminal Dispersal, Fecal Retention, and Related Narrative Matters.” Sinographies: Writing China.

Ed. Eric Hayot, Haun Saussy, and Steven G. Yao. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2007. 355-77.

Olsen, Bjornar. “Material culture after text: re-membering things.” Norwegian Archaeological Review, Vol. 36, No. 2 (2003): 87-104.