tessa wong

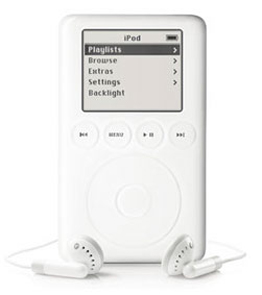

not only is it considered the epitome of the technology used thus far to make portable digital music players (in its vast capacity to hold songs, its size and its weight), but also it has been marketed and fetishised as an object above and beyond all other types of music players or digital music players, so much so that it has become representative of the portable digital music player as well as an icon in modern popular culture. Such fetishism takes place because of its ability to be accessorised, decorated and inscribed.

I aim to discuss how the iPod helps its user carve out one’s personal space within the social in the city, and thus create new dynamics of the relationship between commodity and agent . I will be looking how the relationship is physically manifested and how all these work towards the idea of the iPod as not only an object of utility, but also a medium for transcendence.

If we could now imagine what this young man might experience as he steps out into the city: everywhere, he is surrounded by people, activity, noise – elements of everyday city life. They make up the stress of living in a metropolis which your average urban dweller must face everyday when he steps out from the sanctity of his home, his private space, and out into the social space of the city.

When walking through the city, the urban dweller has to adjust to the oppressive mental life of the metropolis. He has to navigate and apprehend an ‘intensification of emotional life due to the swift and continuous shift of external and internal stimuli’ (Simmel, 1903:325). If Simmel were alive today, he may say that the iPod plays an important part in navigating this intense emotional life, for it helps to recreate ‘the slower, more habitual, more smoothly flowing rhythm’ of small town life – this of course has its own set of problems in its assumption that every single human is born with some notion of the slow rhythm of small town life – hence I will not focus on this aspect.

What is important here is the notion that iPod , as with other portable music players, creates ‘personal space’ for its user. It is through the iPod that he is able to construct his own story within this urban text that he is weaving with other city dwellers. It is a way for him to claim individuality as to his identity – here individuality is seen as hermetically sealing himself off from the world. With each step he is disintegrating the social, the public world (the sidewalk, the street lamps, the fire hydrants), and recreating a personal space. With each step he is only following the most basic of human organisation – the sidewalks that bound him, the traffic lights that tell him when to go and not to go, the subways that take him to and fro his destination on their own schedule not his. He has reduced his contact with the city, and other inhabitants of the city, to the barest minimum.

With each step he is outlining his own trail in the city, and together with his fellow walkers and other iPod-listening people in the city, is writing an ‘urban “text”’ which he writes without being able to read it (de Certeau, 1984:93). He and the other city-dwellers he interacts with on the street are practitioners who ‘make use of spaces that cannot be seen [… and] the paths that correspond in this intertwining, unrecognised poems in which each body is an element signed by many other; elude liegibility. It is as though the practices organising a bustling city were characterised by their blindness. The networks of these moving, intersecting writings compose a manifold story that has neither author nor spectator, shaped out of fragments of trajectories and alterations of spaces: in relation to representations, it remains daily and indefinitely other.’ (de Certeau, 1984:93).

Just as how Graves-Brown points out that the car is symbolic of ‘the progressive use of a fundamentally social product, technology, as a means to neutralise, distance and deny one’s social existence’ (2000:164), so too the iPod works as a continuation of that trend. The creation of a personal space, however arguably illusive it may be, is a demonstration of how such technology creates a ‘physicality of experiences [which] is made entirely private such that the self and others appear to be abstracted’ (2000:161). Graves-Brown argues that ‘surrounded by technology we are no longer fully social beings, and this is partly because we come to forget our embodiment. But more than this our technology, based on a sense of personal freedom, suggests that it will free us from society altogether’ (2000:162).

Which is what the iPod does - it frees him from the constraints of having to interact with other people, and the close claustrophobic pressures of city living, while still allowing us to maintain social relationships with his fellow city-dwellers The iPod then is also used as a flag, a marker, that delineates an invisible boundary of space. And if one chooses to view this in a Durkheimian sense, one can see this iPod-using urban dweller as a social actor, carving out his personal space in the web of relationships with his fellow city dwellers. The iPod is a tool for him to generate personal and mental space within the social urban text of everyday life.technofetishism: technology as extension of man

To listen to an iPod is to signal to others: I am unavailable, do not invade my personal space, to say to oneself and other, ‘I am hermeneutically sealed Man’. As McLuhan points out, it is a process in which one becomes a ‘closed system’ by adapting to one’s extension of oneself - in this case, this extension is the iPod. ‘To behold, use or perceive any extension of ourselves in technological form is necessarily to embrace it. To listen to radio or to read the printed page’ - or to listen to one’s iPod – ‘is to accept these extensions of ourselves into our personal system and to undergo the “closure” or displacement of perception that follows automatically’. And ‘it is this continuous embrace of our own technology in daily use that puts us in the Narcissus role of subliminal awareness and numbness in relation to these images of ourselves’. (1994:46)

Here this is where the iPod distinguishes itself apart from other previous incarnations of portable music players. For its main features are its vast capacity to hold vast amounts of music compared with other technologies, in a digital format; also its design, and marketing of its design by Apple, allows it to be seen as more than just an object – it is a fashion statement, a statement about one’s status in the world, a passport into the culturally relevant realms of society.

It can be dressed up, accessorised; indeed a vast accessories market has sprung up around the notion of being able to personalise one’s iPod. It is able to be inscribed with the owner’s name as well, allowing the user to claim ownership over it. Its blankness is an invitation for the user to personalise it and therefore embrace it further into one’s identity. It is just like how Graves-Brown pointed out, how people choose to personalise their car as well. It is an acknowledgement that ‘technology as an extension of ourselves is part of the self’ (2000:158). And the sense that, just like the car, iPods also have ‘transformed social relations through perceptions of space and time, they have changed work patterns and living arrangements’ (2000:159).If Barthes could say that cars are ‘the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object’ (1993:88) then perhaps we might be able to say the same for the iPod. The iPod has been fetishised through its users who seek to incorporate it within their identity, as an extension of themselves, but also as something more.

Graves-Brown argues against Baudrillard who claims that fetishism of objects creates a hyper-reality. Instead, he posits that technological objects in fact remind their users and humans of their very materiality, their ‘meatiness’ as it were. Here is where I choose to diverge from Graves-Brown’s concept of the technological object as ‘an extension of the body, a form of clothing or perhaps more exactly a second skin or exoskeleton’ (2000:159). For one could also think of the iPod not only as an extension of oneself, but a medium through which the human achieves transcendence. The body and the self can be transcended and extended through this object, to create a personal space within the social. And if one regards transcendence as a quality which is universally human, that is core to what makes us human, then because the iPod helps us achieve this transcendental action of reducing one’s contact with the social to the bare minimum, one might even go so far as to say that the iPod, paradoxically, also helps us stay human.