johanna fausto

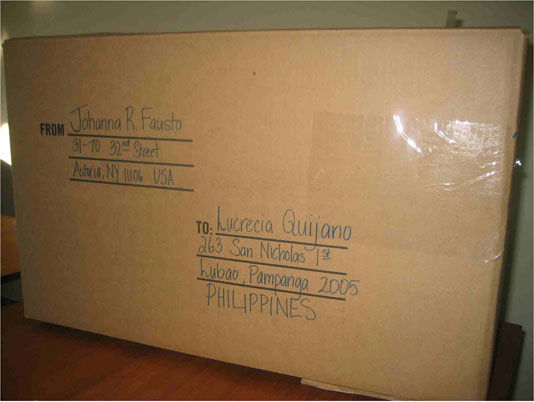

to symbolize a new form of colonialism and hegemonic control over the Filipino people through the distribution of Western commodities of “better quality” (Rafael 1997). In this second object ethnography, I delve into the interior of the balikbayan box to examine its hidden contents. By using theories developed by Jean Baudrillard, Daniel Miller (and by extension Annette Weiner), and Lynn Meskell, I attempt to shed further light on the nature of the relationship between members of the Filipino diaspora and their families in the Philippines as mediated by their engagement with a balikbayan box. My analysis may be useful in dealing with assertions about the hegemonic nature of balikbayan boxes.

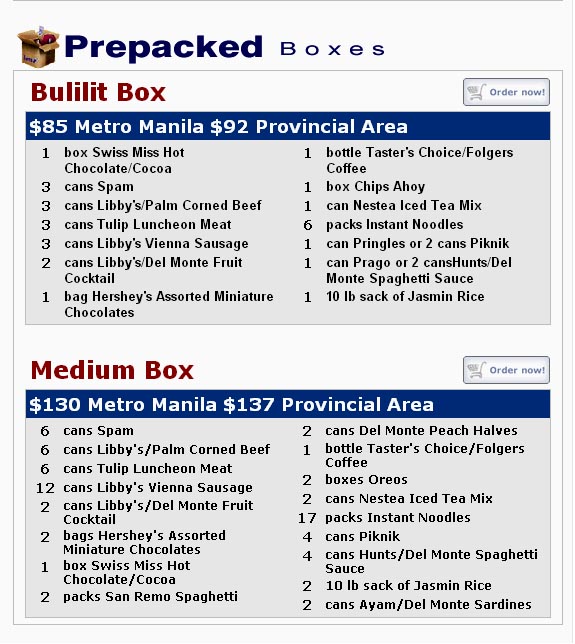

In order to provide an example of a box’s contents, I offer a list of items that have filled my and my mother’s balikbayan boxes in the past. The staples in our balikbayan boxes have usually been: Hershey’s chocolate kisses and miniatures, Nestle Crunch bars, Kit Kats, Snickers bars, Dove soap, Jergens body lotion, Colgate toothpaste, Secret and All Spice deodorants, Lipton tea bags, Taster’s Choice coffee, Sanka decaffeinated coffee, Energizer batteries, and Pantene shampoo. On several occasions, a family member would have a special pasalubong (gift) request, an item with a higher sticker price, such as: a pair of Nike Shox sneakers, a Sony discman, a Coach bag and wallet, a Guess watch, and perfume by Tommy Hilfiger. On the flip side, my mother deemed that some members of her family needed a particular item such as a VCR (replaced by a DVD player also given by her years later) and a blender.

Let us then return to examining the objects at a specific temporal and spatial moment, the period in which they are prepared for placement in a balikbayan box for immediate travel or shipment to the Philippines. Using personal experience as an example, my mother has five siblings still living in the Philippines and my father has two siblings, so each good would come in multiples of seven. A missing item or even worse, an incomplete amount of any one item (less than seven) creates immense anxiety for my mother and me. How can we give one family member Colgate toothpaste without giving it to another? As absurd as this question may seem, all the goods in a balikbayan box must be assumed as one collective set, comprised of multiple collections of each good. As a result of simply possessing an object, Baudrillard argues that the very act of possessing an object allows us to recognize ourselves in that object. For what we collect is really ourselves and through the possession of our object collection do we symbolically transcend death. “If any object’s function—practical, cultural or social—means that it’s the mediation of a wish... the voice of desire... Objects... ensure the continuity of life” (Baudrillard 2005).

Yet my mother and I purchase these commodities for the sole purpose of giving, not keeping. So then, how does one good get deemed important to send and more specifically, how does a particular brand of good get chosen over another? Answers to this question may be elucidated from Daniel Miller’s distinction between alienable gifts and inalienable commodities, the material culture of love, his concept of provisioning (performed mainly by women), and the use of “the long-term brand”. Miller turns around the previously regarded notion that commodities are alienable and gifts are inalienable. He writes, “Inalienability comes mainly through the consumption of commodities and the power of consumption to extract items from the market and make them social or personal... because it is the personal who lies at the core of any local conceptualization of the inalienable” (Miller 2001). A commodity can become inalienable through a process he terms “provisioning” because it has two paradoxical yet reconcilable effects: the subjectification of people by making them sources of desire while simultaneously objectifying the real and imagined relationship between them. Provisioning allows a balikbayan to “recognize as many nuances and subtleties of the relationship as possible” where “the key skill…is sensitivity and a seeming knowledge of what is wanted before the subject realizes he or she even had such a desire,” (Miller 2001) which determines an object’s degree of inalienability. These purchasing decisions obviously vary since relationships change over time but on the whole, this process creates and sustains objects of devotion, or the material culture of love. Mom and I consistently buy Colgate, Hershey’s, or Lipton for our family3 because these long-term brands, defined as “a specific make of commodity that has existed for generations” (Miller 2001) and likened to Weiner’s inalienable objects (Weiner 1992), maintain a level of consistency within a temporal space (generations within my family) in spite of the inevitable and sweeping changes that have happened within that space.4

In order to tie Baudrillard and Miller’s theories together, let me bring in Lynn Meskell’s work which grapples with ancient Egyptian artifacts and their relationship to the people who created and used them. Meskell maintains that ancient Egyptians used objects to not only mediate but also affect their existence between the two worlds, this life and the afterlife (Meskell 2004). Let me assume then, the displacement of an individual through the process of immigration can be described as a symbolic death, where an immigrant’s “new” life in the host country replaces the “old” one in the former homeland.5 Can the questions that Lynn Meskell grapples with in her work be paralleled to my own inquiry? The balikbayan box mediates a balikbayan’s existence in two worlds, a life in the homeland and an afterlife in a new host country. For an ancient Egyptian, certain objects created or gathered in life were specifically set aside in preparation for a more comfortable afterlife. Conversely, for a balikbayan, the objects purchased in the afterlife allow the family left behind in the former life, to experience more comfortable lives. This reason may explain why balikbayans belabor over the shipment of balikbayan boxes instead of simply sending money remittances to let family members shop for the goods themselves. Instead of letting them be troubled, balikbayans trouble themselves for the sake of sustaining relationships with loved ones. Hence, a balikbayan box appears at a Filipino family’s door spontaneously, as if having fallen from the sky, a gift from the afterlife.

The only true source of inalienability comes from reified personhoods according to Miller (Miller 2001). If, according to Baudrillard, we reify ourselves through our object collection, then the balikbayan (giver) undergoes the same process when purchasing multiple items of the same good for placement in a balikbayan box. Through the act of provisioning, the family members left behind in the Philippines (receiver) get reified because a balikbayan directs his/her love to them. So, the personhood of the giver (the balikbayan) and the receiver (the family) get simultaneously reified: the object of desire is the balikbayan while simultaneously the subject of desire is his/her family in the Philippines. Through the consumption of these inalienable commodities do they become personified or socialized (Miller 2001). With the help of Baudrillard, we see that the distribution and the ultimate consumption of Western commodities by loved ones in the Philippines is the way in which a balikbayan gets remembered in the former life. The goods in a balikbayan box are the material manifestations of love between persons as expressed through things. The Colgate toothpaste and the Hershey’s kisses therefore, are personhoods reified. And the temporal and spatial abyss that divides a balikbayan’s old life in the Philippines and his/her afterlife in the new host country is bridged through the shipment of a these goods in a balikbayan box, not in the form of a money remittance.So is the balikbayan box a site for cultural hegemony? I believe it is still premature to answer this question. In the next and final object ethnography, I look at the door-to-door delivery service industry of balikbayan boxes to consider the macro political and economic contexts. Theories on object agency by Alfred Gell and Bruno Latour may also be useful. To recapitulate this discussion for now while preparing to launch into the next, I leave with a quote from Forex, the leading shipper of balikbayan boxes. The company writes on its website, “Forex delivers more than 500,000 balikbayan boxes a year, door-to-door, heart-to-heart."6 Personhoods reified indeed.

(1) Several of these factories actually exist 20 minutes away from my family’s home in the Philippines.

(2) See Vincent Rafael’s essay for further information on the Filipino preference for American products resulting from the far-reaching effects of American occupation in the Philippines from 1898 to 1946, which introduced American concepts, ideals, and goods.

(3) Miller states that mostly women provision since they tended to be the shoppers within the households he studied in London. In this case, my educated guess would be that the women in Filipino households are the predominant decision-makers when it comes to purchasing for items in a balikbayan box. As for single balikbayans around the world, do more women versus men send balikbayan boxes to the Philippines? I do not have the evidence or the answers but it would be an interesting topic to research.

(4) Colgate was not available at Costco one year so mom and I bought Crest toothpaste instead, for the sake of having toothpaste to distribute. When we gave away the Crest in the Philippines, some members of my family were crestfallen (no pun intended) because they looked forward to receiving Colgate, an item they received from us yearly. In effect, many said to us, “Thank you for the toothpaste; we appreciate it very much. But we find that Colgate cleans our teeth better. So if there’s no Colgate at the store next time, then don’t worry about getting us toothpaste.”

(5) This topic can be explored in another paper entirely!

(6) See Forex’s official website for their company tagline.

bibliography

Alburo, Alice Jade A. 2001. Box populi: A socio-cultural study of the Filipino American balikbayan box. MA diss., Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Baudrillard, Jean. 2005 [1968]. The non-functional system, or subjective discourse. In The System of Objects, pp. 75-114. Verso, New York.

Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Clarendon Press, New York.

Kopytoff, Igor. 1986. The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, pp. 64‑94. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Latour, Bruno. 1999. Chapter 6: A Collective of Humans and Nonhumans. In Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies, pp. 174-215. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Meskell, Lynn. 2004. Object Worlds in Ancient Egypt: Material Biographies Past and Present. Berg.

Miller, Daniel. 2001. Alienable gifts and inalienable commodities. In The Empire of Things, edited by Fred R. Myers, pp.91-115. School of American Research, Santa Fe.

Rafael, Vicente L. 1997. ‘Your Grief is Our Gossip’: Overseas Filipinos and Other Spectral Presences. Public Culture, 9(2): 267-291.

Weiner, Annette. 1992. Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping-While-Giving. University of California, Berkeley.