adeola enigbokan

becoming faster and cheaper by the season. This is a world in which I-Pods (digital audio MP3 players) can seriously promise to hold over 10,000 of “your favorite songs,” and memory sticks, smaller than tubes of lipstick, can hold entire films. The aesthetic of memory as objectified commodity, while little addressed in contemporary scholarly work, is not lost on those artists who work within digital vernaculars. In the following sections, I will examine the ideas of one pioneer of modern personal computing and his extraordinary prototypical machine and the work of one digital artist critically engaging questions of objectified memory raised by the new media.

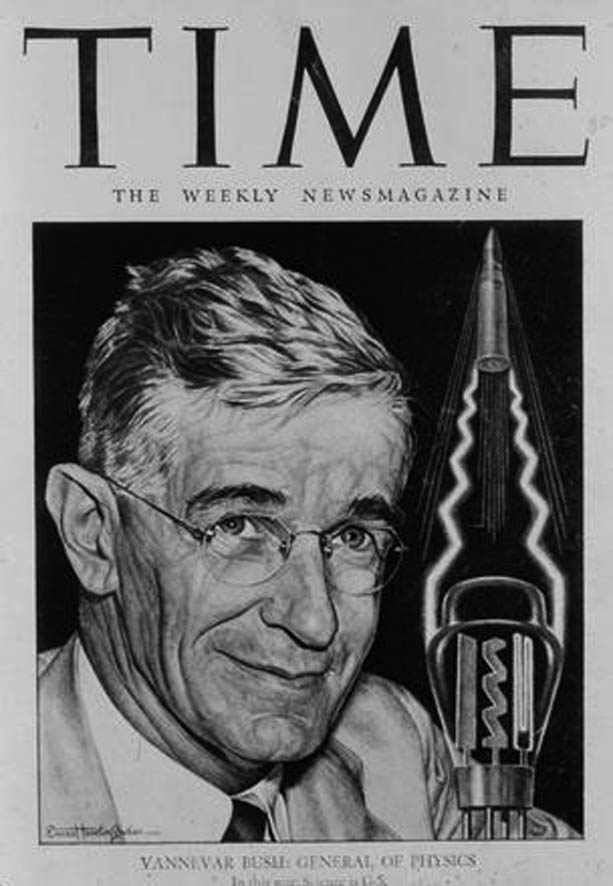

Vannevar Bush and the Memory Machine

In all the arts there is a physical component which can no longer be considered or treated like it used to be, which cannot remain unaffected by our modern knowledge and power. For the last twenty years, neither matter not space nor time has been what it is from time immemorial. We must expect great innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts, thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps bringing about an amazing change in our very notion of art. [1]

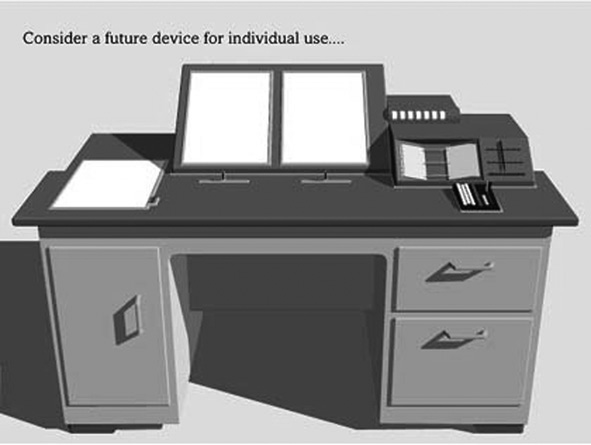

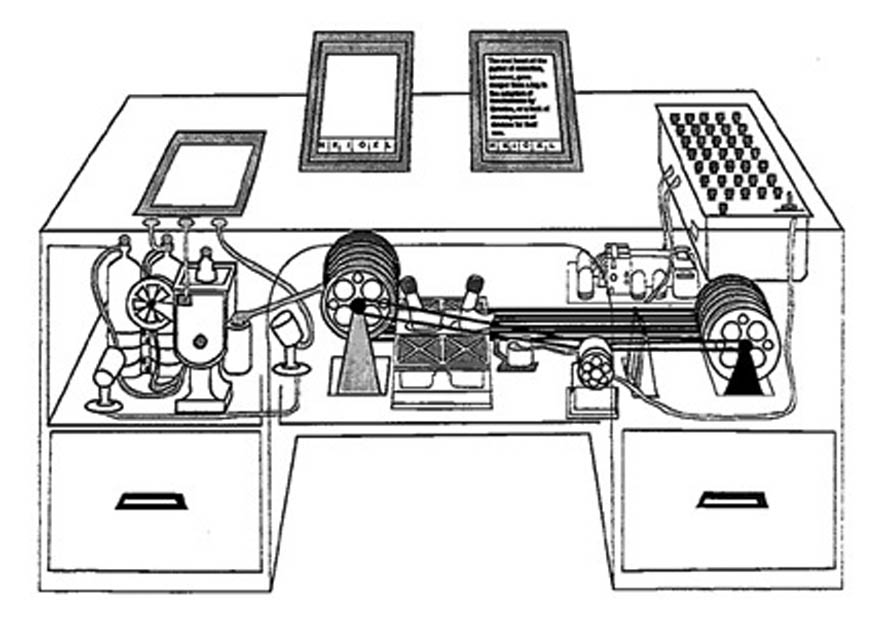

Replacing “the arts” with “information” in the above quotation, from French poet Paul Valery’s study of art in early years of the twentieth century, provides a striking description of information in the age of digital production. [2] In the age of digital production, computer memory is the major “physical component that can no longer be considered or treated like it used to be.” Through the invention and intervention of computer memory, knowledge, transformed into information, or data, can be produced, reproduced or erased with new techniques of data archiving, retrieval and deletion. The pioneers of modern computing were very aware of its revolutionary potential, identifying memory as the main metaphor for knowledge (re)production. Revolutionizing modes of remembering and “augmenting human intellect”[3] became the primary motivation of computer scientists from Vannevar Bush [4] to Tim Berners-Lee. [5] This section examines one of the earliest object-conceptions of personal computing, Vannevar Bush’s “Memex,” as outlined in his 1945 article, “As We May Think.” [6] What are the understandings of human capacities for memory encoded in this machine? In what conceptual and contextual framework does Bush understand knowledge?

At the end of World War II, Bush, who had been a key presidential advisor and coordinator of scientific contributions to the war effort, found himself and other researchers faced with a what he considered to be a new and possible detrimental problem: information overflow. The glut of data, produced by scientists, and other “intellectual workers,” spread out over long distances and across disciplines, were growing increasingly difficult to manage:

There is a growing mountain of research... The investigator is staggered by the findings and conclusions of thousands of other workers. Professionally, our methods of transmitting and reviewing the results of research are generations old... truly significant attainments become lost in the mass of the inconsequential. The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships. [7]

In his characterization of the problem of data glut, Bush’s extremely precise and simple use of language belies the slippages contained in his formulations of research, data, and human experience. The subject for whom information overflow is a problem is the intellectual worker or investigator, whose work is that of “research,” a process composed of the accumulation, review and production of, primarily, written documents. These written documents, important to the work of the researcher, are the measure by which “significant attainment,” in the field of “intellectual work” is judged. For Bush these documents are not only the stock-in-trade of the researcher, but can be conflated with “the summation of human experience,” and human experience is itself assumed to be all that can be appropriately documented. Judgment, between the significant and inconsequential experience is a key technique of intellectual research, and as such is subject to improvement over time. As an identifiable research technique, therefore, judgment or the sorting of data (human experience) through memory, enters the realm of human capacities that are subject to improvement through technological advancement:

MEMEX

Holding the "record of the race"

The personal computer, then, was imagined as sort of individualized bureaucracy. In Bush’s conflation of record keeping and human memory, an organizing principle of modern bureaucracy is revealed. The personal computer, like a national or corporate archive is an ordering device, intended to gather intimate knowledge. All “significant” knowledge available to humans can be stored within the bureaucracy’s files. In the case of national archives, the institution of the state authorizes the collection and organization of intimate knowledge through particular sets of categorizing processes. In the case of personal computers, collection and ordering of intimate knowledge is authorized by the individual user. Bush’s Memex appears to be the forerunner of a future in which personal computing practices will revolve around the manipulation of memory, as object, as commodity, as physical embodiment of imagination and intimate knowledge. This is the future in which artists like Cory Archangel play with these various incarnations of memory, stretching its capacity to abstraction.

Cory Archangel and Technological Nostalgia

Cory Archangel, a founding member of the artists’ collectives, BEIGE and Radical Software Group, is a cracker. Crackers are hackers of obsolete technologies, on the border between the analog and the digital. Like hackers, crackers aim to alter, or recode the technologies they target. Hacking these older technologies, such as old Nintendo Entertainment Systems, or Atari or Commodore 64 computers, however, usually requires literally cracking them open, hence the term “cracking.” Archangel’s fascination with older technologies stems less from longing for times past, than from a distaste for the speed at which technologies are rendered obsolete:

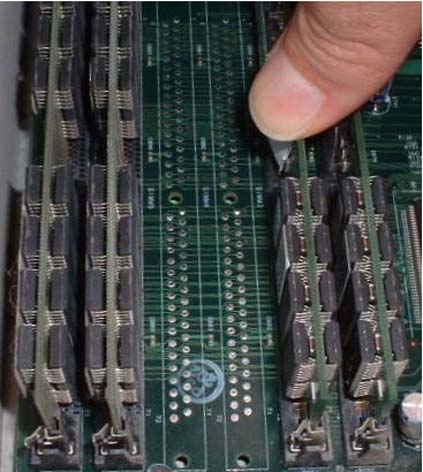

An important aspect of Archangel’s work is the use of the actual language of the computer, ones and zeros, in order to manipulate as closely as possible, the media with which he works. There is increasing distance between people who work with computers in daily life and those who are actually able to manipulate their transformative possibilities. Working with older, simpler technologies, for Archangel, provides a reminder of the creative potential of manipulating computer memory. Noting low image quality and memory on the 8-bit Nintendo system, he reminds readers of the manual, “...hardware limitations defined the aesthetic of most early 80’s video games on the Nintendo, and making art for this system is a study of these limitations.” [12] In its objectified form, computer memory is open to manipulation, not just by the corporate programmers who produce the computer’s architecture, but by all who dare to open them up.

For Archangel, computer memory chips hold the potential for realizing new orders for information. In contradiction to its ordered archival principles, computer systems do not handle erasure well. Discarded items, once deleted, are not actually erased, but merely un-named in the computer’s memory. No longer directly accessible, they exist in the computer’s storage (hard drive) amongst named filed, taking up space and fragmenting memory. These pieces of fragmented memory became the basis of Archangel’s project, Data Diaries. [13] For one month, in January 2005, he recorded the daily activities of his computer’s memory files by feeding them into Quicktime, a digital video application. Flashing and floating across the screen are images, in the color-coded visual language of the computer, representing deleted emails, songs, old Word files, or documents Archangel was working on at the time. The blocks of color, moving manically across the screen creating a vision of life inside computer memory: fleeting, disordered, fragmented. This vision allows for new opening in understanding memory, as filtered through digital formats. As one reviewer described Data Diaries:

Click on images to left to view Quicktime video.

[1] Paul Valery, Aesthetics, “The Conquest of Ubiquity,” trans. By Ralph Manheim, (New York: Pantheon, 1964). Quoted in Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken, 1968).

[2] This interesting exercise was suggested by a friend, Greg Allen, during a conversation about Benjamin’s famous essay.

[3] Phrase taken from Douglas Engelbart’s 1962 project proposal of the same name. One of the early proponents of personal computing, Engelbart is credited with the invention of the computer mouse, and the concept of hypertext.

[4] Bush, first director of the National Science Foundation, and wartime advisor to Franklin Roosevelt, is often referenced as a major influence of future innovators in computer science.

[5] Berners-Lee is credited with the invention of the World Wide Web.

[6] Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think,” Atlantic Monthly (July 1945) p.101-108

[7] Ibid

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., emphasis added.

[10] Excerpted from interview with Cory Archangel, Switch Journal, Summer 2004. http://nxswitch.sjsu.edu/00000c

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid

[13] Data Diaries can be viewed at http://www.turbulence.org/Works/arcangel

[14] Alex Galloway in “Intro to Data Diaries” at http://www.turbulence.org/Works/arcangel/alex.php

[15] Svetlana Boym, The Futures of Nostalgia, (New York: Basic Books, 2001) p. 49

[16] Ibid