meg baker

design and socially ascribed. Kopytoff asks what is the most desirable kind of trajectory an object of its nature could hope for. Moreover, has the object had a successful career? This line of questioning may be especially fruitful when studying objects which clearly aspire to transcend the limitations of their physicality. Many religious icons are mass produced and exchanged in commodity form, yet the intention behind their design necessitates that they take on an importance beyond mere exchange value. The potential for a meaningful “career” is inherent in religious objects, but the degree to which one becomes truly sacred is dependent on its social life after it has been purchased.

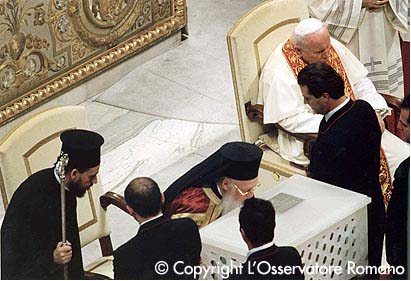

Purchased from the Vatican Museum Store, March 2000

Any Catholic store becomes a venue in which such objects buzz with potentiality. The Vatican Museum Store could then be considered the epicenter of Catholic iconographic production and exchange. In the spring of 2000 I entered the Vatican store to find a quiet religious marketplace where individuals of all creeds gathered distinctly Catholic objects. The store is associated with the Vatican Museum but is rather small and contains almost exclusively religious iconography and few touristy items. Having come to the sensible Catholic conclusion, I decided that if I was ever to purchase a crucifix this was the time and place. Even though I only sought out crucifixes which could be worn on a necklace, the variety was extensive. Price most definitively separated objects into a hierarchy of value. The more expensive the cross and its materials, the more elaborate its packaging and presentation. However, I found the quality of aesthetics to be more enticing than the worth of material and shuffled through traditional crucifixes in the sale section which were mixed together without the luxury of jewelry boxes. The cross I chose was thin and silver with an intricate design. It was crafted from a humble metal yet possessed some kind of higher value and authenticity having been obtained from the core of the Catholic world.

At the time of purchase, the only point at which an object is unquestionably commodified according to Kopytoff, my object ironically received its big break in the career of “thingness”(83). Items purchased at the Vatican are offered a papal blessing free of charge. Having owned the crucifix for only a matter of seconds, I turned it back over to begin a pilgrimage behind the Vatican walls where it would undergo an important spiritual conversion, the details of which will remain a mystery to most. The item was delivered the next day to my hotel. Upon receiving it I could only trust that the blessing had taken place and believe that the crucifix had indeed shed its former identity as a commodity. Thus, this particular crucifix compelled its very first act of faith.

Relics are divided into several categories based on their proximity to an individual who has been beatified. The first class of relics are those which are directly associated with the sacred such as fragments of the true cross or the bones of saints. Objects having come in direct contact with a saint compose the second group. Sulpicius describes the importance of such items as early as the 5th century in the Life of Martin. Pieces of Martin’s cloak and shirt were “tied to the necks of patients [whose] illnesses were frequently dispelled”(Sulpicius, 18.5). The sale of these types of relics is prohibited by church canon. The gap between the earthly object and the divine connection continues to widen as even objects which have come within the presence of the sacred or the tomb of a saint can be considered third class relics. Thus any object, from gold to dust, can be infused with religious significance by simply sharing space with a saint or even a first degree relic. While the church stresses that these objects are not to be venerated in and of themselves, the loose nature of relic production sustains the continued presence and reverence of sacred objects of various forms and degrees of sanctity in Catholic culture.

The sale of significant sacred relics is forbidden, but the sale of objects which may become sacred is basically in keeping with Catholic tradition. The initial commodity form of an object is not exclusionary to its potential to become sacred. Kopytoff terms this transition from commodity form as singularization, also noting it as a process through which an object can become sacred (74). In the case of the crucifix purchased from the Vatican, the object was extracted from the context of the market and elevated for its religious character. Furthermore, it was then singularized through the process of blessing, and consequently separated and made special in comparison to the religious objects left behind at the Vatican. Kopytoff proposes that the non-commodity status of any particular object does not guarantee that it will be held in high regard or considered sacred(74). Nor then should singularization be considered a prerequisite for sacred objects. A commodified object should not be prevented from escaping this phase, and its ability to become sanctified should not be hindered because cultural context is the ultimate determinant of such value.

The identity of the crucifix fluctuates according to its cultural context, which prevents the object from being confined to any particular point along the continuum that exists between commodified and non-commodified forms. The object exists on multiple levels simultaneously depending upon circumstances and perspective. The economic dimension is clear, but the object is also part of a tradition which delineates a historical trajectory that is as much religious as it is political. All of these values along with the sanctity of the object inform the personal relationship with an object. As Annette Weiner describes, this relationship is also informed by the social implications an object can create(34). In Medieval Europe such objects held an enormous amount of significance as arbiters of social power and legitimacy between aristocrats and the church. Today Catholic religious objects are considerably more limited in their political agency. Nevertheless, the ownership and exchange of blessed objects like the crucifix can create a sense of membership and cultural identity while strengthening social ties within the group.

Thus, cultural context is key in discerning the values and characteristics which are ascribed to an object. In the framework of Catholic culture, the commodity status of the crucifix is obscured and overshadowed by its sacred properties. Although the object was manufactured with aspirations to be regarded on more complex levels, outside of its cultural context the item may still be judged according to monetary value alone. Culture is the bulwark which guards against commodification(Kopytoff, 73). Without that protection, an object lies open to multiple interpretations of value which allow it to exist as singularized and commodified simultaneously.

In conclusion, the crucifix purchased at the Vatican has enjoyed a successful career according to Catholic standards having strategically inserted itself into the complex social world of Catholic icons. Although the physical condition of the object has not changed, it has undergone a process of sacralization. The social life of the crucifix has elevated it above commodity status within the Catholic culture even if its commodity value still remains. As Pope John Paul II is considered for canonization, the crucifix confronts another potential milestone. The object has already obtained some sense of legitimacy through its papal blessing. However, by becoming a relic the crucifix is offered the opportunity to identify itself with the very historical process which legitimizes the infusion of sanctity within a commodity, the process which grants validity to its own design, production, and origin.