International Affairs, Suite 1126

International Affairs, Suite 1126

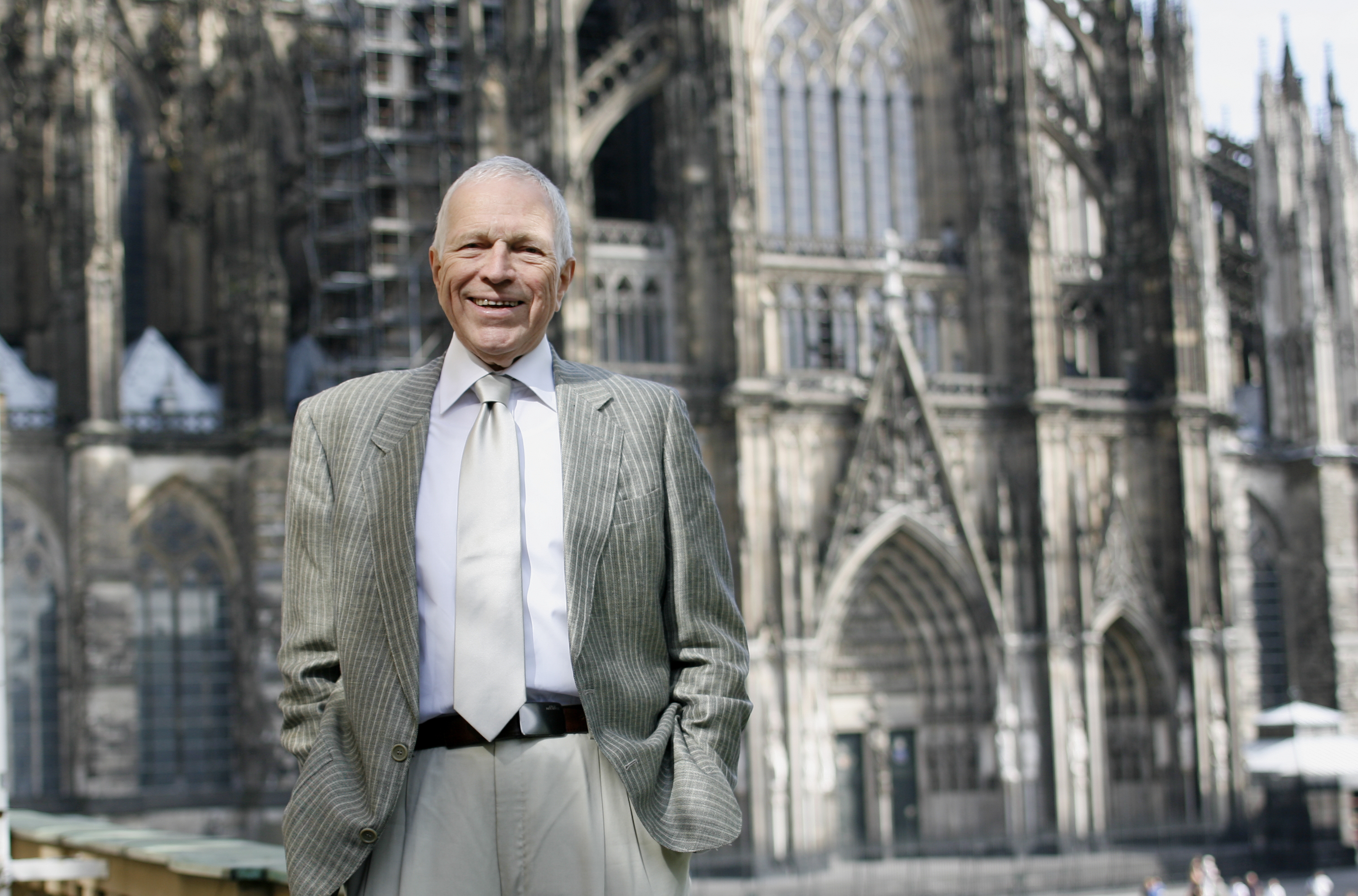

Edmund Phelps, the winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in

Economics, is Director of the Center on Capitalism and

Society at Columbia University. Born in 1933, he spent his

childhood in Chicago and, from age six, grew up in

Hastings-on Hudson, N.Y. He attended public schools,

earned his B.A. from Amherst (1955) and got his Ph.D. at

Yale (1959). After a stint at RAND, he held positions at

Yale and its Cowles Foundation (1960 - 1966), a

professorship at Penn and finally at Columbia in 1971. He

has written books on growth, unemployment theory,

recessions, stagnation, inclusion, rewarding work,

dynamism, indigenous innovation and the good economy.

His work can be seen as a lifelong project to put “people as we know them” into economic theory. In the mid-‘60s to the early ‘80s, beginning with the “Phelps volume,” Microeconomic Foundations of Employment and Inflation Theory (1970), he pointed out that workers, customers and companies must make many decisions without full or current information; and they improvise by forming expectations to fill in for the missing information. In that framework, he studied wage-setting, mark-up rules, slow recoveries and over-shooting. This served to underpin Keynesian tenet that say a cut in the money supply will not merely cause prices and wages to drop with no prolonged effect on employment.

From the mid-‘80s to the late ‘90s, he put aside the short-termism and monetarism of MIT and Chicago to develop a “structuralist” macroeconomics. Contrary to what Keynesian extremists see as unending and unexplained deficiency of “demand,” he sees employment heading to its “natural” level and seeks to explain the effects of structural forces on it. His book Structural Slumps (1994) and later papers with Hian Teck Hoon and Gylfi Zoega find an economy’s natural employment level is contracted by increases in household wealth, in overseas interest rates and by currency weakness. Thus, the big job losses in the US, UK and France result from the pile-up of wealth and puny investment, both stemming from the slowdown of productivity growth.

Now he has worked to put economics on a new foundation. Powerful innovation over more than a century alters the nature of the advanced economies: Having higher income or wealth matters less. As his book Rewarding Work (1997) begins to argue, what matters more are non-material rewards of work: being engaged in projects, the delight of succeeding at something and the experience of flourishing on an unfolding voyage. His book Mass Flourishing (2013) remarks that cavemen had the ability to imagine new things and the zeal to create them. But a culture liberating and inspiring the dynamism is necessary to ignite a “passion for the new.”

Phelps’s work

is best known for introducing in the late ’60s an expectations-based

microeconomics into the theory of employment determination and

price-wage dynamics. Keynes’s great work of the ’30s had left it

unexplained why involuntary unemployment is observed even in the

best of times and why a drop of aggregate “effective demand” causes

a rise of unemployment – why not a prompt fall of money wages and

prices by just enough to forestall a fall of employment? The

challenge was to resolve these issues while continuing to posit the

elementary rationality that economics traditionally ascribed to workers, consumers and firms.

Phelps’s work

is best known for introducing in the late ’60s an expectations-based

microeconomics into the theory of employment determination and

price-wage dynamics. Keynes’s great work of the ’30s had left it

unexplained why involuntary unemployment is observed even in the

best of times and why a drop of aggregate “effective demand” causes

a rise of unemployment – why not a prompt fall of money wages and

prices by just enough to forestall a fall of employment? The

challenge was to resolve these issues while continuing to posit the

elementary rationality that economics traditionally ascribed to workers, consumers and firms. Errors

in wage or price expectations would disturb the volume of

unemployment. If, in the labor turnover model, each firm deciding

its next wage, say, underestimates the wage being set at

the other firms, i.e., the actual wage exceeds the expected wage,

the error reduces the firms’ expected turnover and hence their

expected costs, thus encouraging them to pay less and hire more,

which drives down unemployment. If, in the islands model, the

average wage exceeds what workers expect it is, the underestimate

prompts some workers to accept a job rather than go on searching,

so, again, unemployment drops. In the same spirit, a 1967 paper

supposed that an underestimate by each firm of the price being set

by the others would encourage increases in output supply and labor

demand, raising employment; a 1970 paper introducing the “customer

market,” coauthored with Sidney Winter, supplied a basis for this

idea. From all this, an answer to the puzzle of Keynes emerged: An

unperceived rise in “effective demand,” in driving up the average

money wage and the price level, would reduce unemployment if the

average firm (or island) did not know or imagine that the general

price and wage level had increased by as much as its own – i.e.,

if the actual price or wage inflation exceeded the expected. A

persistent over-estimation of upcoming money wages and

prices could cause a protracted depression. The volume deriving

from a conference Phelps organized at Penn, Microeconomic Foundations of

Employment and Inflation Theory (Norton, 1970), was the

first wave in this new macroeconomics. Applications to demand

management were made in the 1967 paper and in his monograph

Inflation Policy and Unemployment Theory (Norton, 1972).

Errors

in wage or price expectations would disturb the volume of

unemployment. If, in the labor turnover model, each firm deciding

its next wage, say, underestimates the wage being set at

the other firms, i.e., the actual wage exceeds the expected wage,

the error reduces the firms’ expected turnover and hence their

expected costs, thus encouraging them to pay less and hire more,

which drives down unemployment. If, in the islands model, the

average wage exceeds what workers expect it is, the underestimate

prompts some workers to accept a job rather than go on searching,

so, again, unemployment drops. In the same spirit, a 1967 paper

supposed that an underestimate by each firm of the price being set

by the others would encourage increases in output supply and labor

demand, raising employment; a 1970 paper introducing the “customer

market,” coauthored with Sidney Winter, supplied a basis for this

idea. From all this, an answer to the puzzle of Keynes emerged: An

unperceived rise in “effective demand,” in driving up the average

money wage and the price level, would reduce unemployment if the

average firm (or island) did not know or imagine that the general

price and wage level had increased by as much as its own – i.e.,

if the actual price or wage inflation exceeded the expected. A

persistent over-estimation of upcoming money wages and

prices could cause a protracted depression. The volume deriving

from a conference Phelps organized at Penn, Microeconomic Foundations of

Employment and Inflation Theory (Norton, 1970), was the

first wave in this new macroeconomics. Applications to demand

management were made in the 1967 paper and in his monograph

Inflation Policy and Unemployment Theory (Norton, 1972). While these views went on winning support among

macroeconomics experts, the last two decades were testing times.

The ‘80s witnessed a powerful slump in Europe with no evidence of

unexpected disinflation or deflation; the latter half of the ‘90s

brought a strong boom to the U.S. economy and northern Europe

without evidence of unexpected inflation—all contrary to the

simple models. In response, Phelps began in the late ‘80s to

develop a theory of the equilibrium path itself – a theory of the

determinants of the natural unemployment rate. The models built

and their first statistical test were set forth in Structural Slumps: The Modern

Equilibrium Theory of Unemployment, Interest and Assets

(Harvard, 1994). Subsequent papers in this project include

‘Growth, wealth and the natural rate: is Europe’s jobs crisis a

growth crisis?’ ‘The rise and downward

trend of the natural rate,’ ‘Natural rate theory and OECD unemployment,’

and ‘Lessons in natural-rate dynamics.

While these views went on winning support among

macroeconomics experts, the last two decades were testing times.

The ‘80s witnessed a powerful slump in Europe with no evidence of

unexpected disinflation or deflation; the latter half of the ‘90s

brought a strong boom to the U.S. economy and northern Europe

without evidence of unexpected inflation—all contrary to the

simple models. In response, Phelps began in the late ‘80s to

develop a theory of the equilibrium path itself – a theory of the

determinants of the natural unemployment rate. The models built

and their first statistical test were set forth in Structural Slumps: The Modern

Equilibrium Theory of Unemployment, Interest and Assets

(Harvard, 1994). Subsequent papers in this project include

‘Growth, wealth and the natural rate: is Europe’s jobs crisis a

growth crisis?’ ‘The rise and downward

trend of the natural rate,’ ‘Natural rate theory and OECD unemployment,’

and ‘Lessons in natural-rate dynamics.