| ←(Use Google Translate to see an approximate translation into another relevant language) |

[General index] [Index to chapters] [Index to galleries] [Full family history]

Background: I had lived in Germany 1959-61 and gone to an Army high school there, and in many ways it was the best time of my life. When I came back to segregated Virgina for senior year, I hated it. After graduating and working over the summer, I went to the University of Virgina (UVA) in Charlottesville. It was a disaster; I wasn't ready and it wasn't ready. The whole place was just one big drunken orgy, plus it was a patrician bastion of snobbery and white supremacy, "the Harvard of the South". White fraternities with real Black slaves. Anyway, I was paying my own way through UVA and I had used up all the money I earned from my summer job. But not being in college meant being drafted, so I enlisted instead so I could go back to Germany.

In this document:

Mommie, Mommy, Judy = My ex-wife Judith Scott.—Frank da Cruz <fdc@columbia.edu>

You, you guys, Peter, Amy = Judy's and my children Peter and Amy da Cruz.

Ludwig = A friend from junior and senior high school in Arlington Va.

Roger Anderson = Army buddy 1963-65.

Kinapic = A rustic "housekeeping cottages" place on a lake in Maine where we used to go every summer when Peter and Amy were little.

Most recent update: 30 March 2024 20:52:24

The Army – 1963-1966

[SEE GALLERY]

|

| Official photo |

|

| My dogtags and P-38 1963 |

I was in the Army from February 6, 1963, to February 2, 1966. My dad was furious when I dropped out of UVA, I thought he was going to kill me, literally. I had really had enough of him so without telling anybody, I went and joined the Army, and that was the last time I ever saw my family together. I joined the Army because I knew I would be drafted anyway, but if I enlisted I could pick where they sent me. And I picked Germany. Actually it was a bit more complicated… if you enlisted you could pick an overseas AREA (Asia or Europe) and the BRANCH (Infantry, Artillery, or Armor) and so, knowing that all the Armored units in Europe were in Germany, I picked Armor and Europe. For my dogtags I had to put a religion, so I put Sodothic (a made-up religion) on one, and Taoist on the other (compare with my father's WWII dogtags). The other thing with the dogtags is my P-38, explained below. Hey, didn't I get dogtags made for you guys once at the Army exhibit at the Addison County Fair in Vermont? (I was 48 years old and they tried get me to re-up!)

Anyway, 1961-62 was just a big gap, a wasteland. I hated Virginia, the cliquishness, the segregation, my school, the suburbs, the car culture, everything. I was still angry that my dad had screwed up and got us kicked out of Germany a year early and all I really wanted was to go back, and I did. Pretty amazing my plan actually worked, I might have wound up in Vietnam, which in early 1963 I had barely heard of.

|

| Fort Holabird had a Sphinx |

|

| Fort Holabird, Maryland |

It was either at Fort Gordon or Fort Knox, I was invited to go to OCS — Officer Candidate School — so I could be an officer instead of an EM. I had zero desire to be an officer.Physical exam, signed the papers, took the oath at Fort Holabird*, 6 February 1963

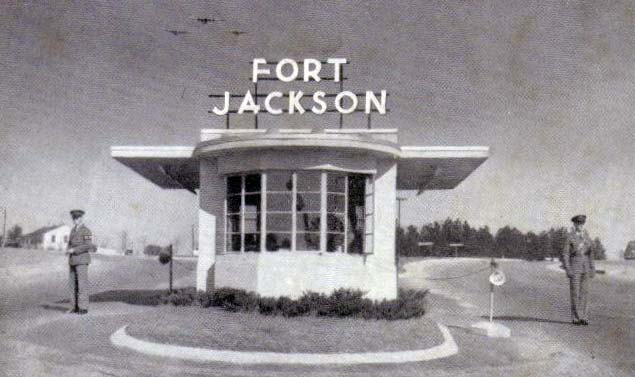

Reception center at Fort Jackson SC (near Columbia) - about a week

Basic training at Fort Gordon GA (near Augusta) - 8 weeks Company B, 2nd Batallion, 1st Infantry Regiment (where I saw Cubans training for a second invasion that never happened**), Military Occupational Specialty: 111 (Infantry)

A week's leave where I traveled around visiting people and spent a night in jail.

Reconnaisance (scout) training at Fort Knox KY (near Louisville) - 8 weeks New MOS: 112 (Cavalry Scout) Took an overnight bus from DC to Louisville that went through West Virginia on 2-lane Route 50 through the Appalachian mountains to Cincinnati and from there to Louisville on a highway.

A week at Fort Dix NJ waiting for ship to Germany.

USNS Geiger (troop ship) from NYC to Bremerhaven Germany - about a week.

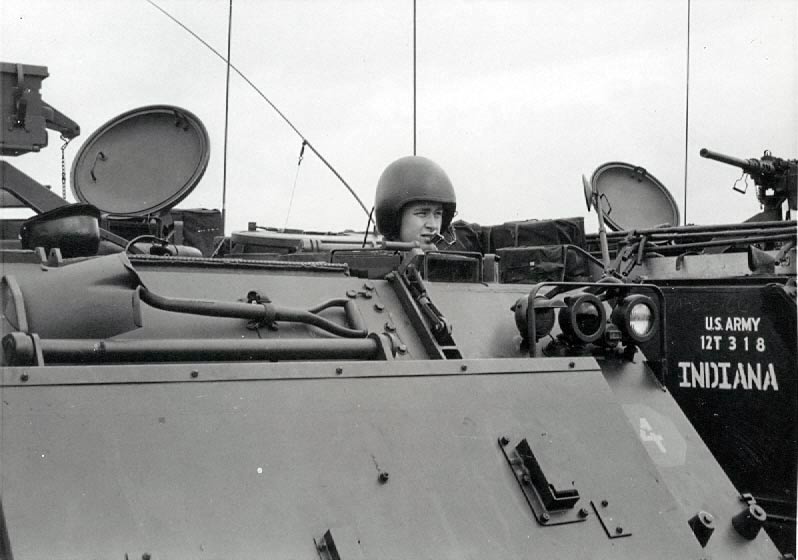

About a year and a half (1963-64) at HQ Troop, 3rd Reconnaissance Squadron, 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, 7th US Army, Kaiserslautern, Germany (Vogelweh Kaserne, near Hohenecken) with tank range at Grafenwöhr and field maneuvers up to a month long. I had many jobs there ranging from office work (because I could type), motor pool, marriage counselor (really), garbage dump detail, etc. Office work was like Radar in MASH: morning reports, cutting orders, filling out forms, etc, all done by manual typewriter. Motor pool was maintenance of jeeps, armored personnel carriers, and tanks. Also in those days everybody took turns doing guard duty and working in the mess hall (KP = Kitchen Police about one day a month), taking garbage to the dump (for this I drove trucks or stood in the back of them, waist-deep in garbage). Of course everybody also had to do cleaning in the barracks, offices, and other places — scraping, sanding, waxing, and buffing wood and linoleum floors, etc. "Policing" the area around the barracks each morning, i.e. picking up beer bottles and cigarette butts. We worked Monday through Friday plus Saturday mornings. Sometimes instead of working on Saturday morning, we'd have a parade, complete with Army marching band playing Sousa marches and the occasional improbable sentimental song like "Memories". I did good work, I reached the rank of SP4 (Specialist 4). Although my Primary Military Occupational Specialty (PMOS) was Cavalry Scout, never actually did that after Fort Knox. I also worked as a "personel" specialist (716), orders clerk (711), key punch operator (761)… MOS's have totally changed several times since the 1960s. The reference for when I was in the Army is US AR 611-201 June 1960, but I can't find a copy.

About a year at 7th US Army HQ in Stuttgart/Vaihingen, Germany, attached to Command and Control Information Systems (CCIS), Resident Study Group (RSG), an early computer prototyping project, with a month's "computer school" in Orléans, France, in April 1965. Not actually *in* Orléans, but in the forest somewhere a few miles from there, along a dirt road. The school was a little group of Quonset huts, some for work, others for barracks, and one as a mess hall. It was almost like camping out. Then back to Stuttgart.

Back to NYC (Brooklyn Navy Yard, Fort Hamilton) by USNS Geiger sailing from Bremerhaven, a week at sea.

Released February 2, 1966.

Ready Reserves until February 6, 1969 (they never called me up, even though the Viet Nam war was in full swing).

Service number: RA13786982. In 1963 they said I'd never forget it, and so far I haven't). RA means Regular Army as opposed to draftee [US] or National Guard [NG].

| * | Fort Holabird closed in 1973, no trace remains except a Holabird Avenue. |

| ** | About the Cubans… I could hear them speaking Spanish, and their sergeants and officers spoke to them in Spanish, which just does not happen in the US Army. We weren't allowed to get anywhere near them but sometimes it couldn't be avoided. I could see that unlike us, they had no markings whatsoever on their fatigues — no "US ARMY", no name tag, nothing. I mentioned this to Tom Hayden about 2015, when he was writing Listen Yankee, and he put my story at the end of an article he had written on Cuba and the assassination of JFK. Tom died in 2016 and his website tomhayden.com is gone as of 2017. He was a founder and hero of the New Left for nearly fifty years. |

| Unit | Sub-units | Soldiers | Commander |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fire team (Infantry) | — | 4-5 | Sergeant |

| Squad | 2 fire teams | 9-10 | Staff Sergeant |

| Platoon | 2 or more squads | 16-40 | Lieutenant |

| Company / Troop* / Battery† | 3-5 Platoons | 100-200 | Captain or Major |

| Battalion / Squadron* | 4-6 Companies | 300-1000 | Lt. Colonel |

| Brigade / Regiment* | 3-5 Battalions | 1500-3200 | Colonel |

| Division | 2-4 Brigades | 10,000-16,000 | Major General (2 stars) |

| Corps | 2-5 Divisions | 20,000-45,000 | Lt. General (3 stars) |

| Army | 2-4 Corps | 50,000 or more | General (4 stars) |

Reference: Survey of U.S. Army Uniforms, Weapons and Accoutrements by David Cole, US. Army Center of Military History.

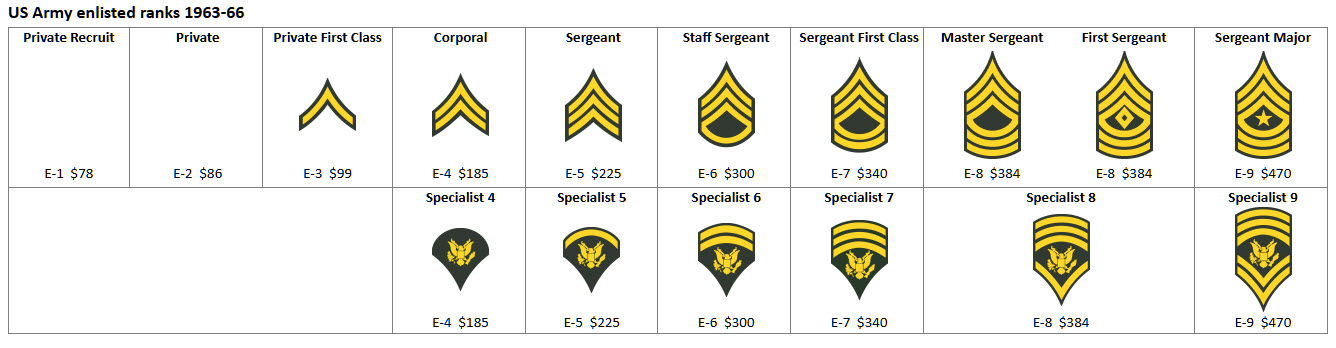

Click the image below to see a table of US Army enlisted ranks in 1963-66, plus some explanation:

Reception Center at Fort Jackson, South Carolina

|

| Fort Jackson SC 1963 |

It was quite a shock… The minute you arrive they are yelling at you, insulting you, and making you run everywhere, dickhead. They shave off all your hair, and if you have any cavities they pull the bad teeth out. You have no rights, no privacy; they punish people at random for no reason. They don't let you sleep, they don't let you rest. They give you good food and then don't let you eat it... GET OUT! GET OUT!.

At first I thought I had stumbled into some kind of rogue outfit, but the shouting, profanity, insults, cruelty towards the most vulnerable, the arbitrary punishment and scapegoating, sleep and food deprivation, etc, were standard. Some people couldn't take it, but for me it wasn't much different from "Life With Father". A week of that, then on to Fort Gordon, Georgia, for Basic Training.

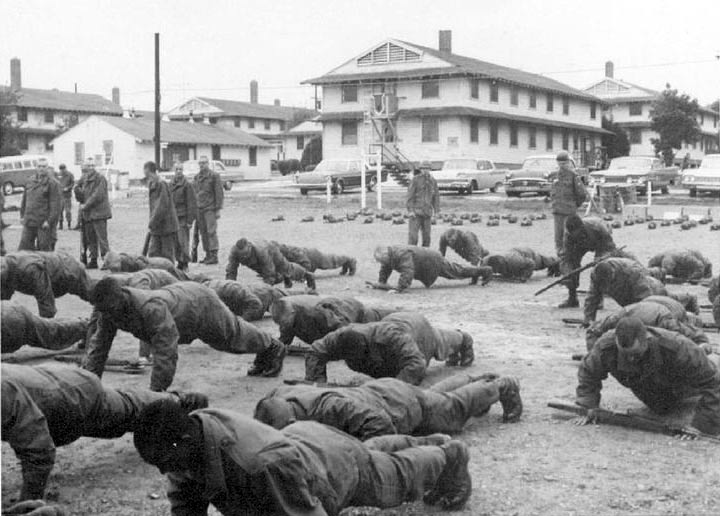

Basic Training at Fort Gordon, Georgia

"Shit, shower, shave, and shine" Like at least eight other southern Army bases, Fort Gordon was named after a Confederate general; all nine renamed in 2023-24[1,2]. I don't have any original pictures of my Army training, but these from Google are pretty much how I remember it: the old two-story WWII-era wooden barracks and M1 rifles... At Fort Gordon, we were treated the same as at Fort Jackson, but now at least here was a routine. They woke us at 4:00 or 5:00am (or as early as 1:00am if you had KP) and made us stand in formation outside in the cold February air for an hour or two before letting us go for breakfast... and maybe even letting us eat it.

|

| Tons of pushups all the time |

|

| First introduction to the M1 rifle |

|

| The gas chamber (older photo) |

Back in the barracks after dinner in the mess hall, we'd have to be constantly shining our brass and polishing our shoes and boots and also keeping the place clean, because there could be a surprise inspection at any moment, and the tiniest speck of dirt or wrinkle on a bedspread would result in mass punishment. At least once we week we had to strip the wax from the floor and rewax it. Every morning it had to be buffed, but I liked doing that, the buffer is fun. But with all that there might be only 30 minutes of free time for the trainees to write home before lights out.

Some of the drill sergeants were pyschos and alcoholics, like Sergeant Goo (really) who lived with us in the barracks because his wife had thrown him out, and he would usually pass out on floor some time before lights out, but before that he'd be telling the sad tale of his life, always ending with "If the Army wanted you to have a wife, they'd issue you one". Others were more straight-arrow and super-tough on physical training. One of these had fought in Korea and he was haunted by how it was the flabby out-of-shape guys who got killed, so he wanted us to come out of Basic with the endurance of Zulus. He told us about his time in Korea towards the end of Basic, the first time he ever sat down with us and just talked instead of barking orders and insults. His name was Sergeant Swenby (pronounced Svimby). His favorite saying (when he wasn't showing his human side) was "Only three things I hate in this world: cold coffee, wet shitpaper, and Got-Damn Train-ee!" (the 't' in Got represents a prolonged glottal stop). Instead of saying "everybody" he said "sick, lame, and lazy".

When marching, there was always an NCO (corporal or sergeant) who marched alongside calling cadence. White sergeants like Swenby used a lot of glottal stops... Hut Haw Hut Haw Your Left Right Left (the t's being glottal stops). But Black sergeants were super creative, they'd accentuate the downbeat, make a poem or a song or a chant out of it, make up crazy words, etc, it was almost a pleasure to march with them. Sometimes it would also be call-and-response, like a work song. Thinking back, it was kind of cool how we evolved from a bunch of clumsy stumblebums into a crack marching outfit. Sounds dumb for me of all people to be saying that but there was some satisfaction in it.

|

| Entrenching tool |

Most guys were totally cowed by the cadre, but one guy sticks in my mind, he was from NYC, probably Brooklyn; Italian or Jewish. If a cadre told him to "get down and give me fifty" or whatever he'd say "Fuck you, cracker, YOU get down and give ME fifty!" He didn't take abuse from anybody, it was a real eye-opener. The amazing thing was, he pretty much got away with it; he was tough, they respected him. That was one of things that attracted me to NYC.

|

| An Army rifle range 1960s |

I'm pretty sure the firing range at Fort Gordon was 500m, the targets were so far away you could hardly see them. There was also another range where you had to walk forwards and then shoot cardboard enemies as they popped up.

We had one overnight pass in Basic, so a bunch of us took the bus to Augusta to (what else) go drinking in bars. In those days Augusta was pretty much just a one-street sleazy "strip" full of bars and clip joints. There were six of us, 3 white, 3 black. We probably tried to get into 20 different bars and not one would let us in. We kind of expected it but still... this was a town that depended almost totally on an integrated Army base for its livelihood (yes, they also have the Masters golf tournament but that's only for a short time each year). Anyway we tried. Then went back to base for some near-bear at the snack bar. That was the closest I ever got to a Freedom Ride because I was in Germany during the real Freedom Rides.

The song that sticks in my head from Basic is "Our Day Will Come" by Ruby and the Romantics. Also "Two Lovers" by Mary Wells; "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah" by Bob B. Soxx and The Blue Jeans (early Phil Spector Wall of Sound remake of my first favorite song when I was 1 or 2 years old), and "Walk Like a Man" by the Four Seasons, not because I liked it but it kept going through my head during forced marches when I had an untreated bone fracture in my foot. Also, not a song but whenever we had to "charge", people would always yell Yabba-Dabba-Doo! (from the Flintstones).

- Why Does the U.S. Military Celebrate White Supremacy?, New York Times (editorial), 23 May 2020.

- DOD to change names of nine Army installations by 2024, jbsa.mil, 14 April 2023 (accessed 1 January 2024): Forts A.P. Hill, Benning, Bragg, Hood, Lee, Pickett, Polk, Rucker).

Interlude

We had a week or two off after Basic. I took a bus from Augusta to Charlottesville with a stop in Fayetteville NC to see my old friend from Frankfurt HS, Jerry Jacobs, at Fort Bragg. Called his house, his little brother answered, Jerry had just been killed in a car crash.Continued to UVA, met up with Ludwig. He said I was totally transformed, all tanned, hard, and muscular with my buzzcut. We went on a road trip in his 1953 Buick (he didn't care much about school). There was a third guy too but can't remember who, Don somebody?. We drove diagonally southwest for a date that had been arranged with three girls at Hollins College* in Johnson City*, Tennessee, friends of Ludwig or the other guy, I didn't know them. It was a beautiful drive, kind of like rural Vermont, passing through Lynchburg, Roanoke, Blacksburg, and the rest was pretty much backwoods; about 250 miles all together. We arrived at Hollins in the evening, picked the girls up, drove back to Bristol (which straddles the VA-TN border), bought a case of beer and were drinking it in an empty parking lot in the dark when the police came and arrested all six of us and hauled us off to jail. I think this was in the Virginia half of Bristol. We slept, woke up to a breakfast of hard stale bread, fossilized baloney, and super-harsh black coffee in metal cups, were taken across the street to the courthouse where the judge said "Well, y'all look like some nice young boys and girls (i.e. white ones), I'm gonna let you off with a warning but don't ya'll let me catch you in here again, y'heah?"

So far so good. Now to drive the girls back to Hollins. They had missed curfew at school and were afraid they might be in trouble. When we arrived, the entire road that led from the Hollins gate to the buildings was lined with people waiting to see the fallen women after their night of sin (there wasn't any sin, we went straight to jail). We felt awful but since they were immediately taken into custody there was nothing we could do, so we left.

Later I found out the three girls were expelled from Hollins. I didn't even know them. But still, not exactly one of my happier memories. Soon after, Ludwig dropped out of UVA for the same reasons I did, was drafted or enlisted in the Army, and wound up in Vietnam**. Although I did see him once later on, I don't know anything about his time there. I assume he was in combat because he rose to Staff Sergeant (E6) in only one 2-year hitch.

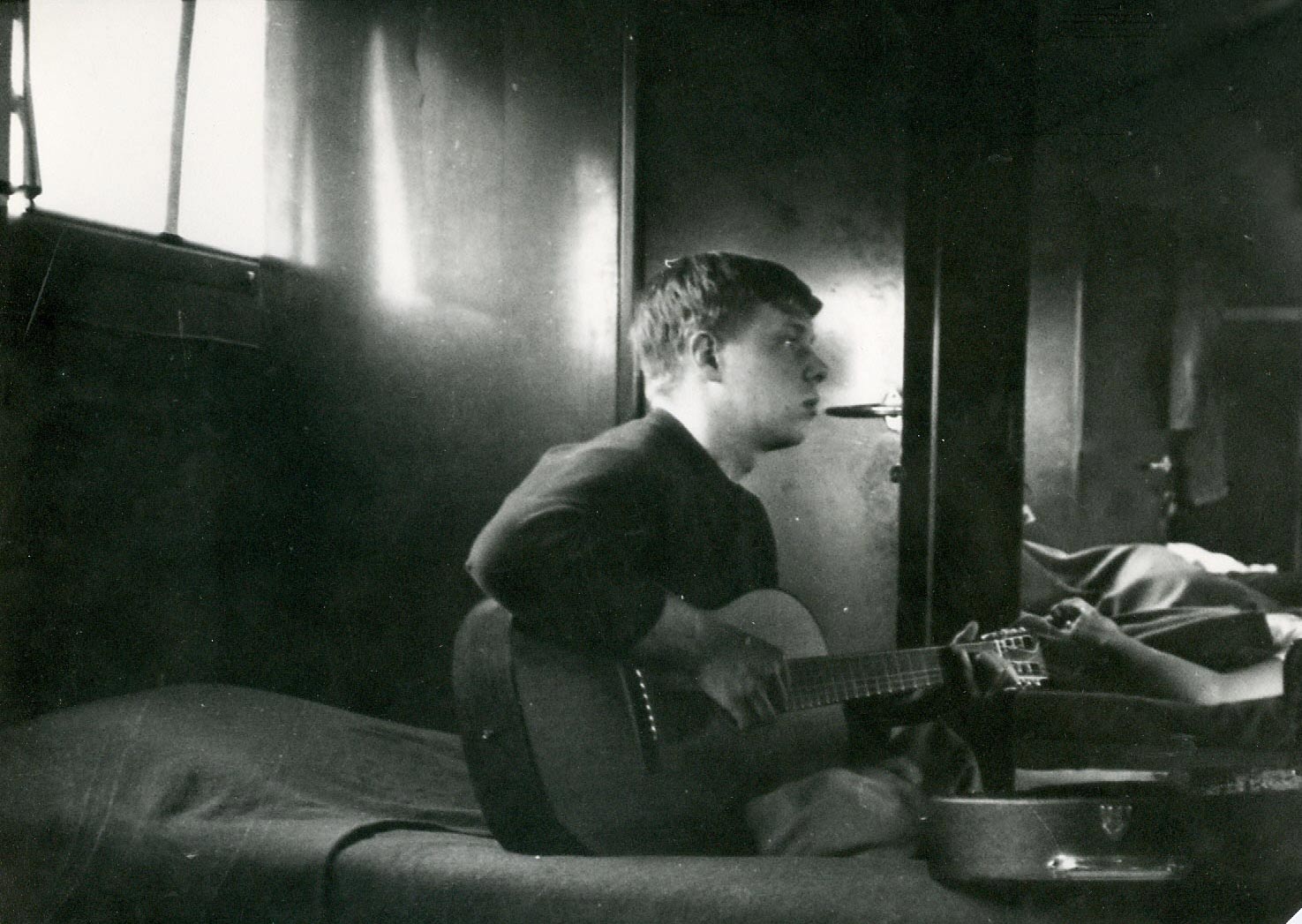

The other thing that happened when I was on leave was that I bought the Martin O-16 that I still have, at Sophocles Pappas in DC. April 1963 for $110 new with my Basic Training pay (I only earned $78 a month but since there was nothing to spend it on I had more than enough for the guitar). I've had it with me wherever I lived ever since.

| * | All of this is from memory sixty years later. I know for sure that we went to Johnson City to pick up the girls, and I know we were arrested in Bristol. But Hollins College was not in Johnson City, Tennessee, it was in Roanoke, Virginia, and we definitely did not go there! Ludwig mentions a Sullins College, but it was in Bristol, not Johnson City. If that was the college where the girls were, why did we go to Johnson City? As far as I can tell, the only college in Johnson City in 1963 was East Tennessee State College (now University), which was and is co-ed, but I seem to remember the college the girls were at was all girls. Oh well, it was nearly sixty years ago as I write this. |

| ** | Ludwig and I reconnected briefly in 2022 and there's lots more to his story to be filled in, e.g. that he wasn't drafted until 1967. |

Scout Training at Fort Knox, Kentucky

Vacation over, I took an overnight bus to Louisville, Kentucky, where Fort Knox is. The bus went along Route 50, a winding mountain road through West Virginia that ends up in the flatlands of Ohio and then the bluegrass of Kentucky.Now it was time for 8 weeks of Armored Cavalry scout training, which was lots of fun. Once you get past Basic they're not mean to you any more and you have free time and freedom to go anywhere. Fort Knox is HUGE and has about a dozen movie theaters and free buses that take you all over. One Sunday, Roger and I went to four movies, 25 cents each.

|

| Jeep training |

|

| Machine gun mounted on Jeep |

|

| Jeep in water |

|

| M2 .50 caliber machine gun |

We learned about azimuths and radians and coordinates, and how to call in artillery fire. We learned to estimate distances and sizes of far-away things and how to orient maps and to navigate by dead reckoning, shadows, and tree-moss. We learned how to classify roads, tunnels, and bridges and how to blow up bridges and railroad tracks. We learned to fire and take apart and put back together every kind of gun the Army had: The WWII M1, the M2 50-caliber machine gun (which is still in use even though it's 100 years old), the M60 machine gun, the M3 45-caliber "grease gun" (submachine gun), the M-1911 45-caliber pistol, the M79 grenade launcher… and we also threw real hand grenades. Every boy's dream! (Seriously, boys are fascinated by this stuff… I never wanted to kill or hurt anybody, but getting to shoot all these guns… what can I say?) The firing range at Fort Knox for the M2 machine guns was 500 yards, five football fields, almost a third of a mile. At that distance, those guns could knock down big trees.

|

| He looked like this |

Roger Anderson

[See gallery]

|

| Roger Anderson 1965 |

|

| Sharon Robinson and Roger 1972 |

|

| Roger Judy Sharon in Wyoming |

|

| Berchtesgaden poster |

|

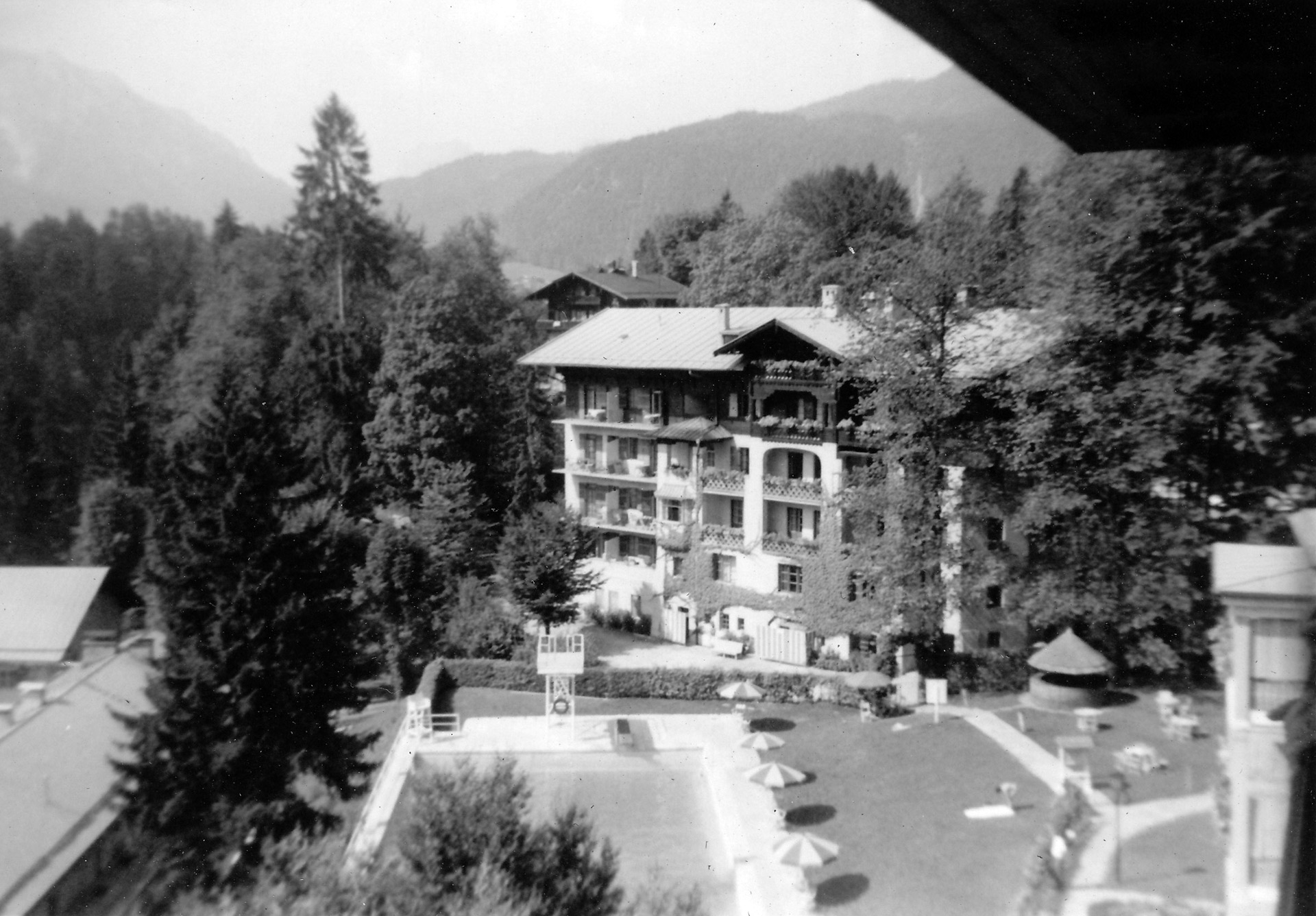

| General Walker Hotel Berchtesgaden |

|

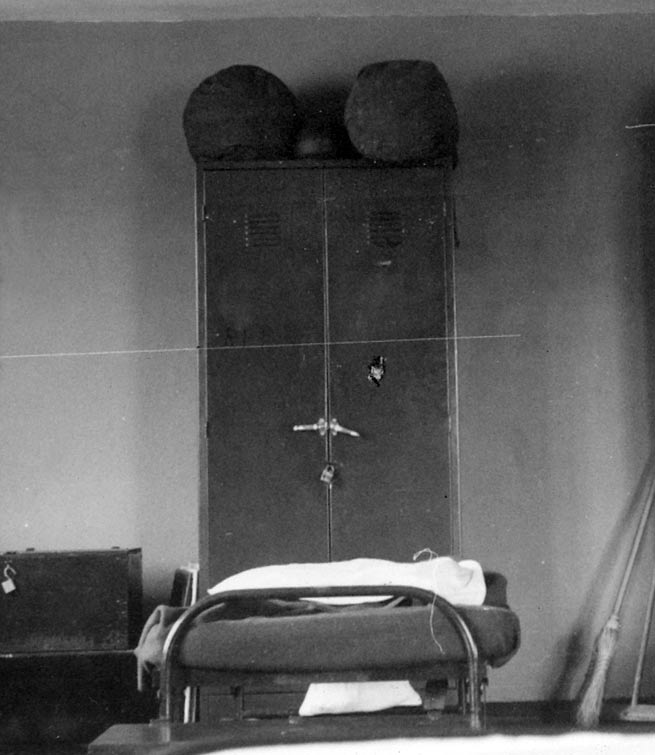

| Army bunk and wall locker |

|

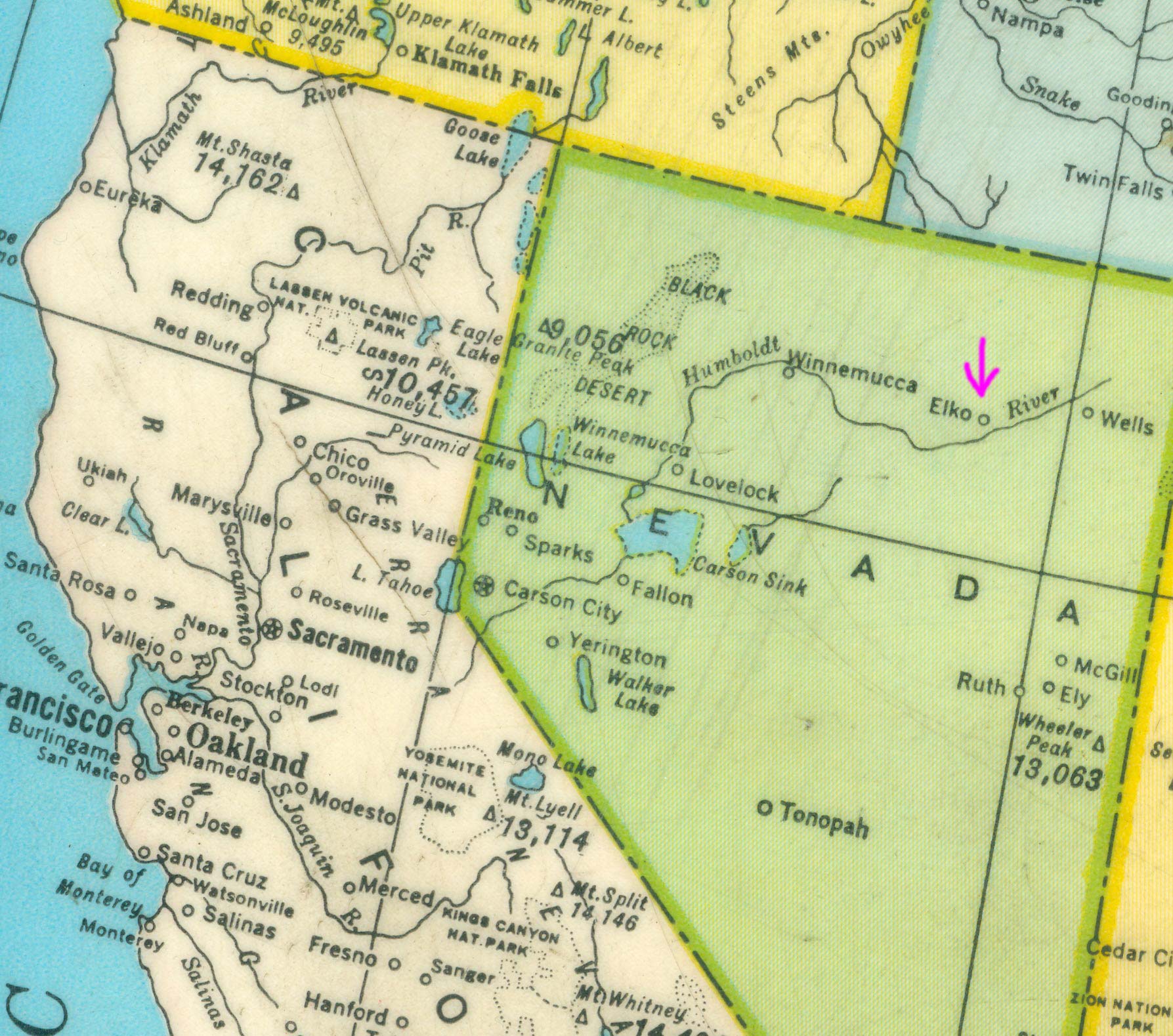

| Elko on the map |

Roger's family was Swedish; his dad worked for the railroad. Before Roger was born, every day his dad would bring home some railroad ties. When he had enough, he built the house where the family would live. They kept a lot of Swedish traditions, like Christmas morning his sister Sandra would come down the stairs with candles on her head. One Christmas she sent me a BIG box full of home-made chocolate chip cookies and "fattigmankakas*", a kind of Swedish thing… Let's see if I can describe it… Dough rolled thin, cut in a longish rectangle, then a slit is made toward one end, and the other end is twisted and then pulled through it, sort of like a Möbius strip, and then it is baked until it's crunchy and sprinkled with powdered sugar. And the packing material was Cheerios, probably ten big boxes of them! That was one of my most appreciated Christmas presents ever. I guess that happened when she was 24 or 25 (I was 19). She died in May 2020 at age 78 of aortic stenosis.

Sharon Robinson (in the pictures) was a friend of Mommie's and one of my favorite people of all time, we used to see her constantly in the 70s but I don't know what happened to her after that. Once she made me a big thick knitted scarf that I still have.

| * | A word I never encountered again until nearly 60 later when I read Wisconsin, My Home by Thurine Oleson, University of Wisconsin Press (1950), about 19th-century Scandinavian immigrants. "Fattigmankakas" are "poor man's cookies". |

3rd Armored Cavalry, Kaiserslautern, Germany

|

| L Troop, 3rd Reconnaissance Squadron, 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, 1963 (I was in HQ Troop - no group picture for us!) |

|

|

Third Armored Cavalry fatigue shirt 1960s |

|

|

Third Armored Cavalry Regimental pin |

At the end of scout training at Fort Knox we found out where our final

posting would be, and mine turned out to be the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment

in Kaiserslautern,

Germany, which is in Rheinland-Pfalz,

about 66 miles southwest of Frankfurt. Roger too. We were sent to Fort Dix

NJ to wait for transportation to Germany. We were there for a week, totally

free to wander around and do whatever we wanted. Once day we bought some

beer and went in the woods to drink it in a creekbed. Next day I had my

last and possibly worst case of poison ivy ever. I couldn't use my hands at

all so when it came time to board the troop ship USNS Geiger

(T‑AP 197), Roger carried my duffle bag and guitar along with

his own stuff... and duffel bags are heavy! Thanks, Rog (more about

the Geiger here).

|

| Deuce-and-a-half |

I was to find out only 50-some years later that I am descended from farmers in the tiny villages Steinwenden and Krottelbach, that were literally walking distance from my barracks in Vogelweh. They lived there in the late 1600s and early 1700s before emigrating to Pennsylvania and Maryland.

|

| Snack Bar and barracks |

|

| Kapaun Kaserne 1963 |

In the Cavalry you don't have companies (like Company A, Company B), you have troops, like F Troop and L Troop. And you don't have batallions, you have squadrons. Roger and I were assigned to "Headquarters and Headquarters Troop" or HHT, the headquarters of the squadron.

|

| 3rd ACR headquarters and barracks |

Operation Big Lift

Soon after we arrived was our first big deployment, Operation Big Lift, October-November 1963. Quoting from the Army history page:

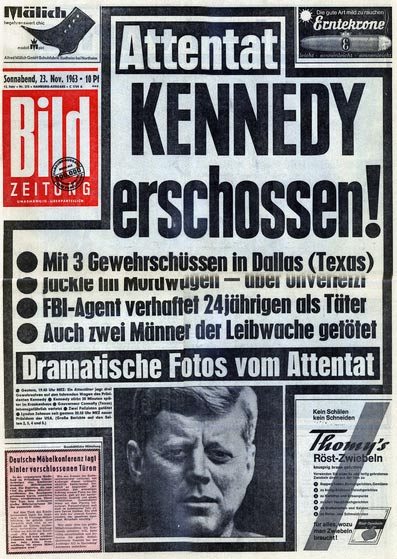

The 3rd Infantry Division played the enemy (ORANGE) force. Elements of the 8th Infantry Division, the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, and a reinforced Panzer Grenadier Battalion from the III German Corps served as the friendly (BLUE) force. Altogether, nearly 46,000 personnel, 900 tanks, and hundreds of trucks and armored personnel carriers participated. The Air Force flew 759 sorties in support as well. Ultimately, BLUE proved victorious, but not before it was nearly overrun by ORANGE and suffered heavy damage in the partially choreographed battles.In a speech slated for November 22, President Kennedy planned to tout it as proof that the nation was 'prepared as never before to move substantial numbers of men in surprisingly little time to advanced positions anywhere in the world.' The address, however, was never given. Earlier that day the president was gunned down by an assassin.

I don't know if we even knew Big Lift was such a big deal at the time. All I remember is being in the mud, mostly in the woods, for weeks and weeks, relocating periodically to another muddy forest two or three times. If we were in any battles, I didn't notice (I was probably working in the Heaquarters tent the whole time). More about the Kennedy assassination below.

Back on base...

|

| C-ration can |

|

| P-38 all-purpose tool (1 inch long) |

|

| Shit on a shingle (SOS) |

In spite of the good mess-hall breakfasts many of us often went to the Snack Bar to buy breakfast for a nominal fee, just to be in the presence of the German girls who worked there, and also there was a juke box. The song that was almost always playing was "Where Did Our Love Go" by the Supremes.

The mess hall also made special Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners but one year when we filed in for our Thanksgiving dinner, we got C-Rations! All the turkeys, hundreds of them, had mysteriously disappeared. Army Quartermasters ("procurement specialists") were notorious wheeler-dealers, selling everything from penicillin to Jeeps on the black market. Maybe mess sergeants too! But they weren't all bad. One time we arrived back at base at 3:00am, tired, wet, and miserable after being in the field for several weeks in constant freezing rain. The mess sergeant greeted us with fresh coffee and a huge batch of hot-from-the-oven home-made chocolate-chip cookies. This same sergeant was very fond of his block hat, he never took it off, and consequently it developed quite a grease stain around the rim (the standard thing to say about that was "hey, when you gonna get the oil changed in that hat?"), but the funny part was that every time he bent over a big pot that he was stirring, the hat would fall into it.

Also Kaiserslautern's main Snack Bar (which was normally just a big cafeteria) turned into an almost-elegant restaurant one Thursday per month for Steak Night... dim lighting, music, tablecloths, candles, waitresses and busboys from the high school, and delicious meals served on china. Rog and I never missed it!

|

| Me at Grafenwöhr in 1964 |

|

| Grafenwöhr tank range |

|

| Luxembourg American Cemetery 1964 |

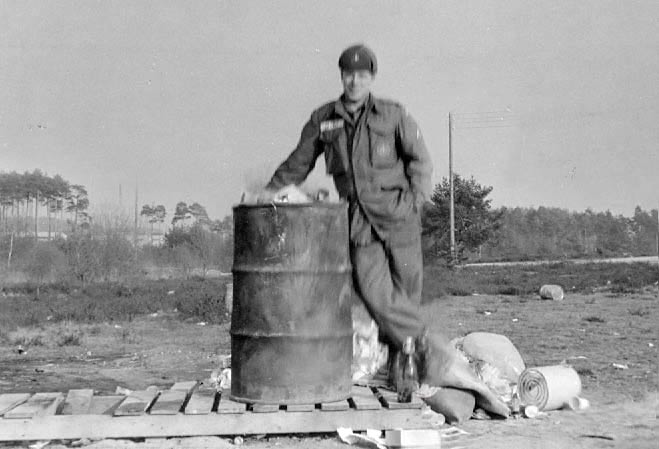

One day at Graf I was on garbage duty in a deuce-and-a-half picking up garbage and taking it to a huge burn pit. We were backed up to the edge of the pit along with about ten other big trucks, shoveling out the garbage, when a large amount .50-cal ammunition started going off… belts of M2 machine-gun ammunition, big heavy bullets flying in every direction. All 10 trucks took off like race cars! (Sixty years later burn pits are very much in the news with so many veterans sick from exposure to all the toxins and our gridlocked congress unable to appropriate the funds needed for treatment.)

|

| Army coal stove |

|

| Mickey Mouse boots |

One night at Graf they threw a surprise party for us, turning the huge mess tent into a giant beer hall and everybody could have all the beer they wanted for free. Local (northeast Bavarian) German beer. I guess they had a slush fund for this kind of thing.

|

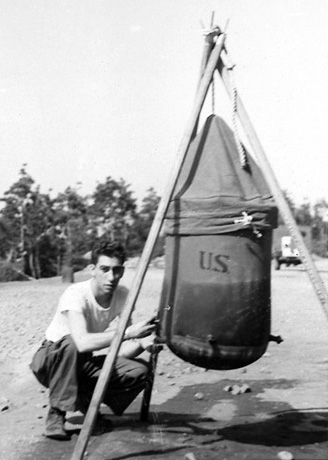

| Lyster bag |

|

| Army mess kit |

|

| Army poncho |

|

| Army field kitchen |

The prevailing odor around an Army base or bivouac in those days was coal smoke and diesel fumes. Strangely enough, it was not entirely unpleasant.

Hohenecken

|

| Hohenecken seen from castle 1964 |

|

| Hohenecken from castle 1964 |

|

| Hohenecken 1975 with castle |

|

| Hohenecken Gasthaus postcard |

|

| Die Oma and Judy 1975 |

At one point Roger and I registered for a night-school Russian course at the University of Maryland extension on base in Kaiserslautern High School. After class we'd go to Oma's to do our homework over a delicious home-cooked dinner. We would sit at the table by the window in the picture at the bottom right on the postcard. At the lower left is the larger dining room, where once we had a unit banquet for 15-20 people and Oma cooked Rouladen for everybody, which is rolled-up beef with stuffing and gravy.

|

| My lockers and bunk |

|

| Armored Personnel Carriers at river crossing |

|

| Birdie driving APC |

|

| Tanker boots |

|

| PS Magazine |

The color item is a 1964 issue of Will Eisner's PS Magazine, the monthly Preventive Maintenance magazine distributed all over every Army base everywhere, humorously explaining how not to screw up the multitude of little jobs we had to do, especially in the motor pool.

|

| Kapaun Kaserne motor pool |

|

| M60 tanks |

|

| M60 tanks on train |

|

| APCs in the field, taking a break |

On war games, we'd sleep in our individual canvas pup tents in sleeping bags (made of cloth and feathers) on top of inflated rubber mattresses, which we'd inflate with jeep exhaust. This was a non-waterproof alternative to the shelter-half method described earlier. I would usually be working in the big CP tent, morning reports or whatever (simulated casualties). One night when I was sleeping a pipsqueak second lieutenant threw a live tear gas canister into my pup tent! You know, to test my READINESS...

On a more serious note, once I was kept back from maneuvers for some reason, to hold down the fort or whatever. I was on KP in the mess hall, working in the kitchen, when one of the cooks came and gave me a bucket and a sponge and sent me to the clipper room at the opposite end, which is where they wash the trays and cups and bowls, and get to work on the wall and the radiator. Because it was simulated combat, even those of us who remained on base were armed and wearing combat gear. Some guys in the clipper room were horsing around... actually I don't know what they were doing, but a gun went off and the bullet exploded a guy's head. I didn't even hear it. The MPs had already come and gone; they had cut out the piece of the plywood wall that had the bullet hole but left behind all blood, brains, skull fragments, scalp and hair on wall, floor, and radiator, and I cleaned it up.

Anyway, field maneuvers could have been fun... They start with a huge convoy of trucks, Jeeps, APCs, and tanks going for hours along narrow secondary roads through small villages and finally entering a forest somewhere and making camp. The way I remember it, every single time it was bright and sunny when we set out, but as we approached our destination there were huge black clouds looming overhead, and when we arrived it was pouring erain, and we lived in rain and mud the whole time.

On another big exercise I didn't go on, when an M108 self-propelled Howitzer was going through a little village, its radio antenna made contact with a power line, which started a fire, which caused the thing to explode and everybody in it was killed.

|

| Milk dispenser |

|

| Kennedy Erschossen |

B-girls, as you know, were just working girls whose job was simple, you buy them drinks and they sit and talk with you. Of course the waiters bring them fake drinks with no alcohol, so they can do it all night. I found out that JFK was killed from a B-girl at a bar in Kaiserslautern. She had just heard it on German radio, she told us how it happened… his motorcade was going over a bridge, and he was shot from a boat below. She drew a diagram on a beer coaster with a ball-point pen. I wish I had saved the beer coaster. About two minutes later the MPs came crashing in and loaded us on 3/4-ton trucks back to base. We stayed up all night in the barracks with loaded guns and full combat regalia waiting for the Soviet tanks to come rumbling across the Fulda Gap but by midday the next day (Saturday) nothing had happened, so since WWIII didn't start they un-canceled all leaves and passes and Rog and I went to Frankfurt to see if anybody was still there that I knew, and sure enough Virginia Search, who was a cheerleader with my ex-girlfriend Pam, was there and since her dad was an NCO she took us the NCO club for lunch, even though Rog and I were only privates. Then we went to check out the high school and in a Felliniesque touch there was a circus underway on the athletic field; an elephant broke loose, crashed down the fence and ran away down Siolistrasse. That night or the next, I was in a station of the new Frankfurt U-Bahn (subway) when a newsboy came running down the steps, screaming the headline "Kennedys Mörder Ermordet!". Kennedy was adored in Germany because he came to Berlin after the Wall went up and said "Ich bin ein Berliner!" Every shop window had a shrine to him and this lasted for many years.Speaking of B-girls, it was said that in Kaiserslautern (which had a huge proliferation of American military bases), 50% of the German population was on the KGB or HVA payroll, including probably 100% of the B-girls. It was not uncommon for a girl to sit down with you in a bar and start asking questions like… Which Kaserne are you at? Which unit? How many tanks do you have? What kind? Where is the ammunition stored? I always answered all their questions.

|

| Das Spinnrädl |

|

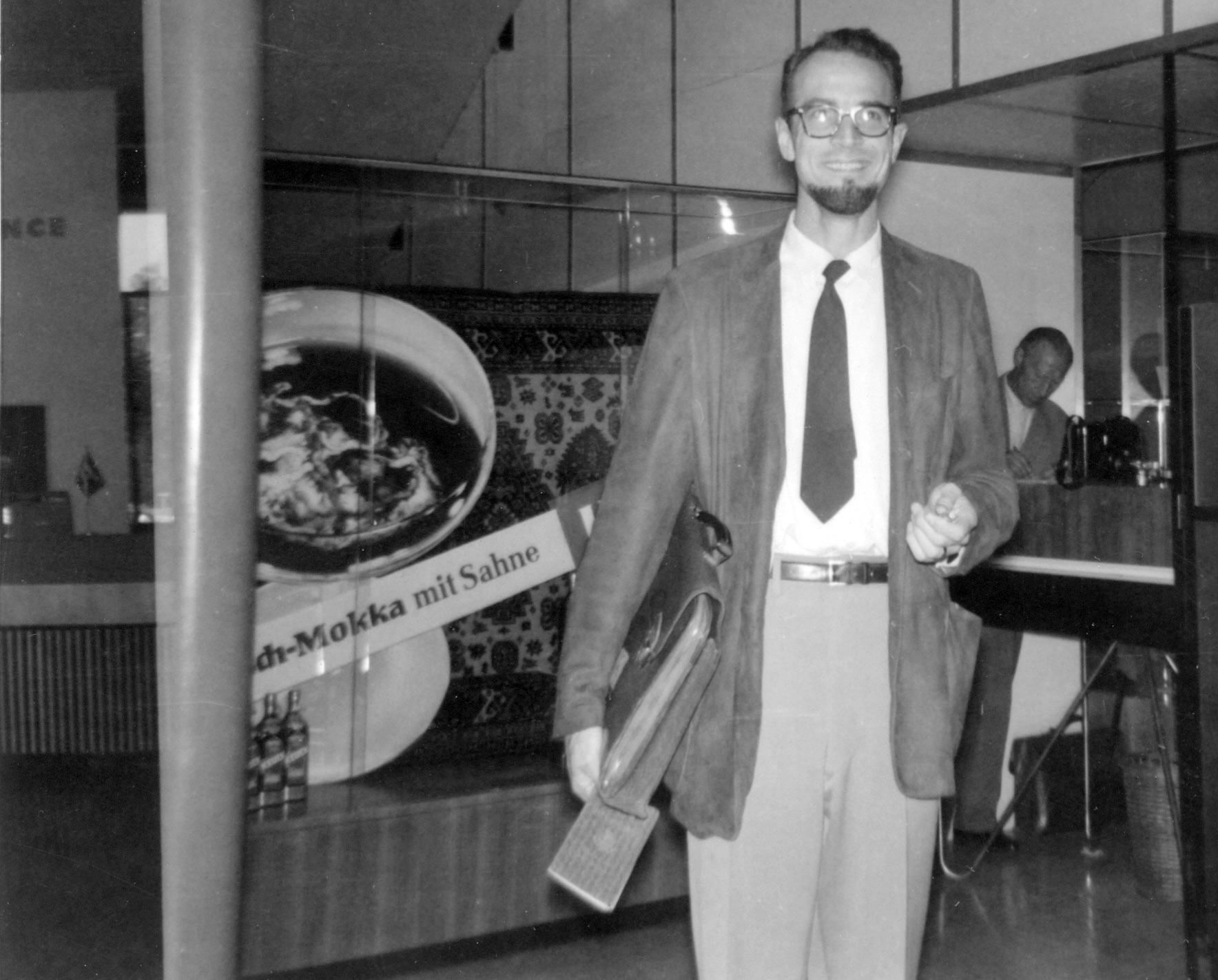

| Uncle Pete at Frankfurt Book Fair |

(I know I said something like this before, but it bears repeating...) Being in the Army was like living in a socialist economy. You worked, and in return all the essentials of life — food, clothing (uniforms), lodging, medical care, even tailoring and laundry — were totally free. Even college courses in night school. Furthermore, in those days there were no corporate concessions on Army bases… no Pizza Huts, McDonalds, Starbucks, big-box stores… Everything was government and nonprofit. Even the food in the mess hall was non-corporate, like the famous "government peanut butter" — no brand names. You were paid a salary but you had no fixed expenses or bills, so you could use your money for whatever you wanted. As a PFC (1963) I earned $99/month, and as an SP4 (1965) $185. Dollars went a long way in postwar Germany, where you could get a good meal in a restaurant for four Marks (a dollar), trolley fare was maybe 15 cents, a half liter of beer was a quarter. The stores and restaurants on the base (PX, snack bar, EM club) were nonprofit and subsidized, and there were tons of facilities available to use for free: gyms, music rooms, pool and ping-pong tables, bowling alleys, running tracks… and theaters that showed first-run movies, admission 25 cents.

Just a few years later the dollar-Mark exchange rate got so bad that GIs could barely afford to go into town. But staying on the base was still like socialism with nonprofit subsidized housing for dependents, excellent schools for dependent children, nonprofit supermarket ("commissary"), free medical care for the whole family, etc. Not to mention service clubs (that served alcohol), movie theaters, libraries, etc. Besides military people and their families, all this was also open to DAC's — Department of the Army Civilians — such as my teachers or, for that matter, my own father (DAC was his CIA cover in Germany). If you have ever lived this way, you see see dog-eat-dog capitalism in a whole different light.

Since all essentials for living were provided, if you lost your entire paycheck on payday in a poker game (as many GIs did) you could still eat, have a place to live, get medical care, and have your laundry done. All without money. (But if you had a family, their food was not free, so it was bad news for a married GI to lose his whole paycheck; nevertheless, it happened a lot.)

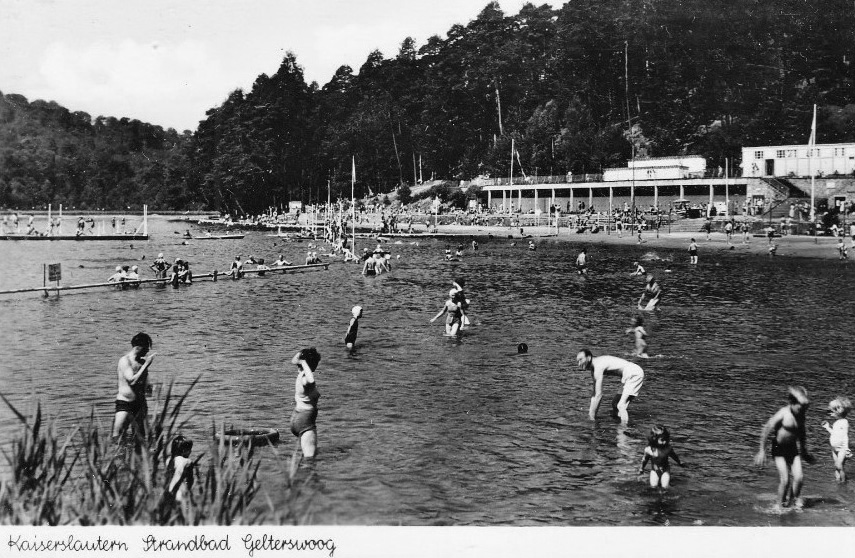

|

| Gelterswoog |

|

| Gelterswoog |

DP camp

|

| Forest near Kaiserslautern |

The story of the DP camps is told in DPs: Europe's Displaced Persons, 1945–51 by Mark Wyman (Cornell University Press, 1989-1998). The camps were administered by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), and by 1951 (or, according to Wikipedia, 1957, or 1959 at the latest) all DPs should have been resettled or relocated and all the clamps closed. Anyway the camp Roger and I saw was in the middle of nowhere; the country names on the buildings were in English and it had the look of a US Army post. It seemed to be deliberately isolated and hidden. By the way, an excellent movie about DPs in postwar Germany is The Search, Fred Zinnemann (1948), with Montgomery Clift, filmed on location in the rubble of Germany with actual DPs.

Theater group

|

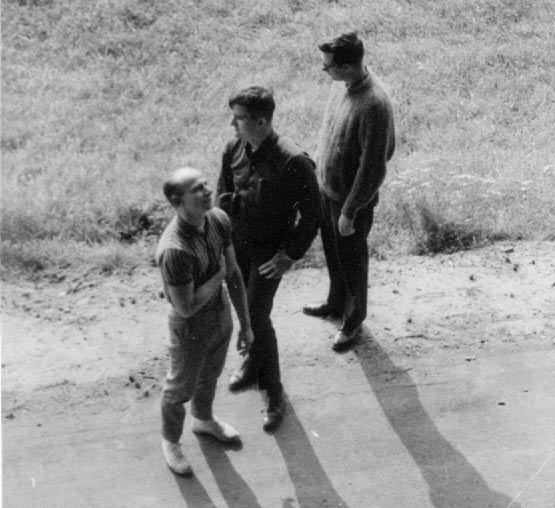

| Barnes, Munn, and Stewart |

|

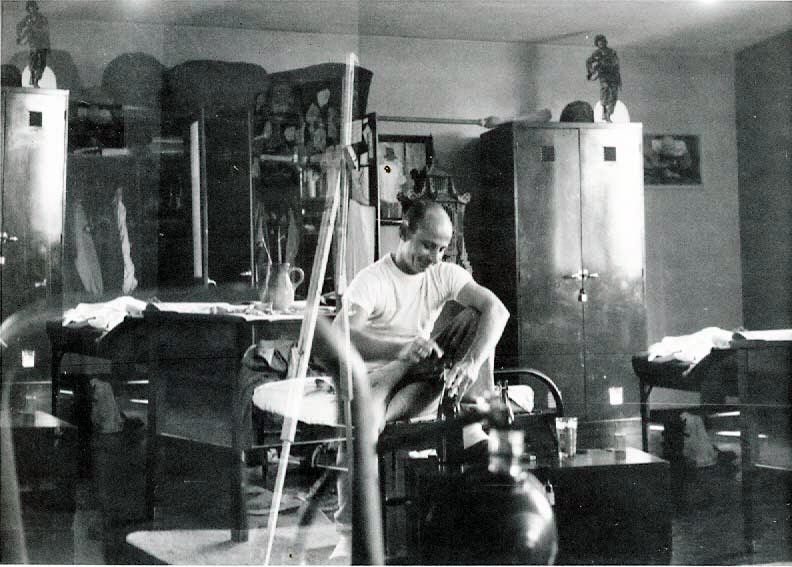

| Barnes on a Sunday |

|

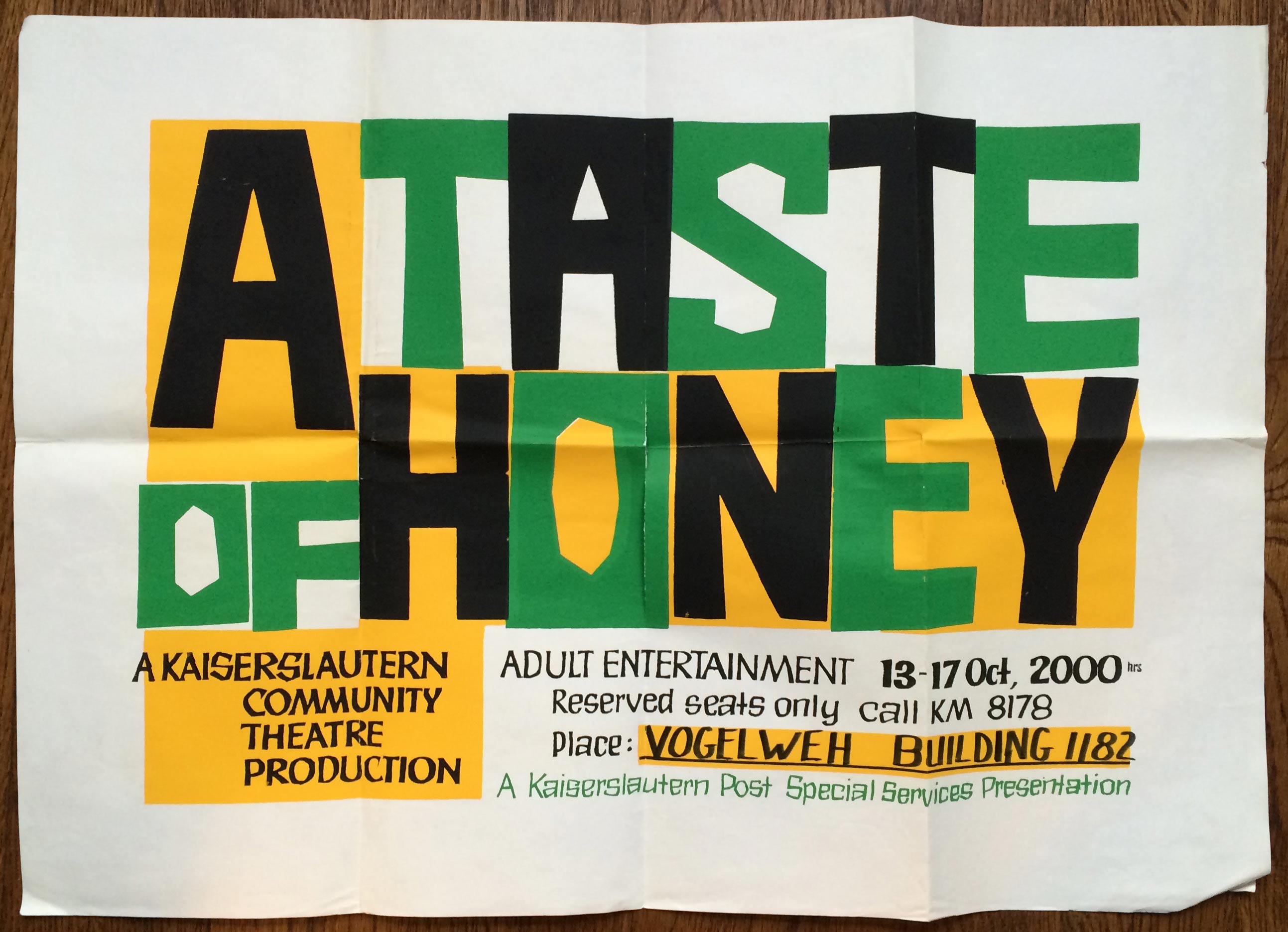

| "A Taste of Honey" poster 1964 |

|

| Program page 1 |

|

| Program page 2 |

|

| Program page 3 |

|

| Program page 4 |

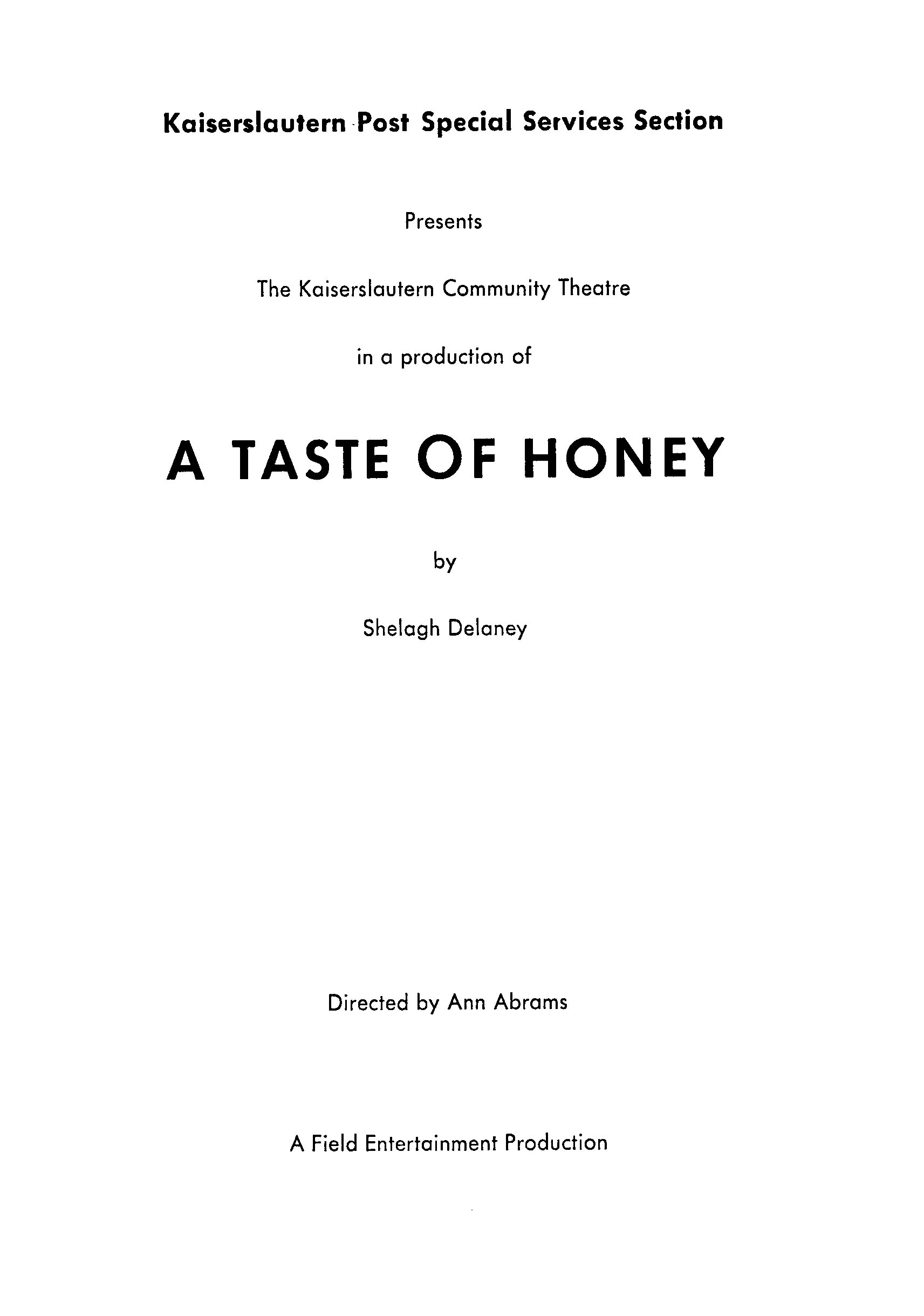

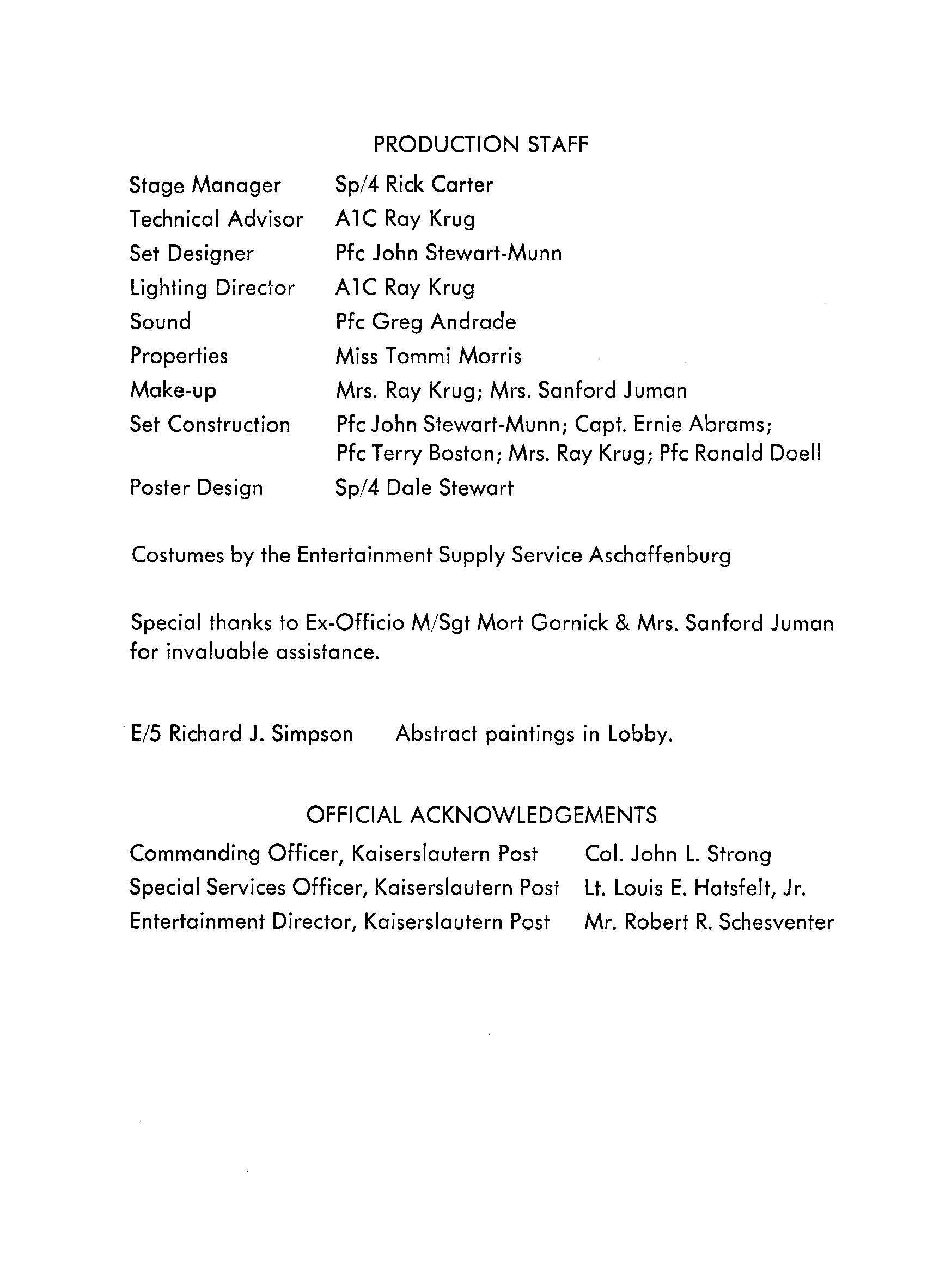

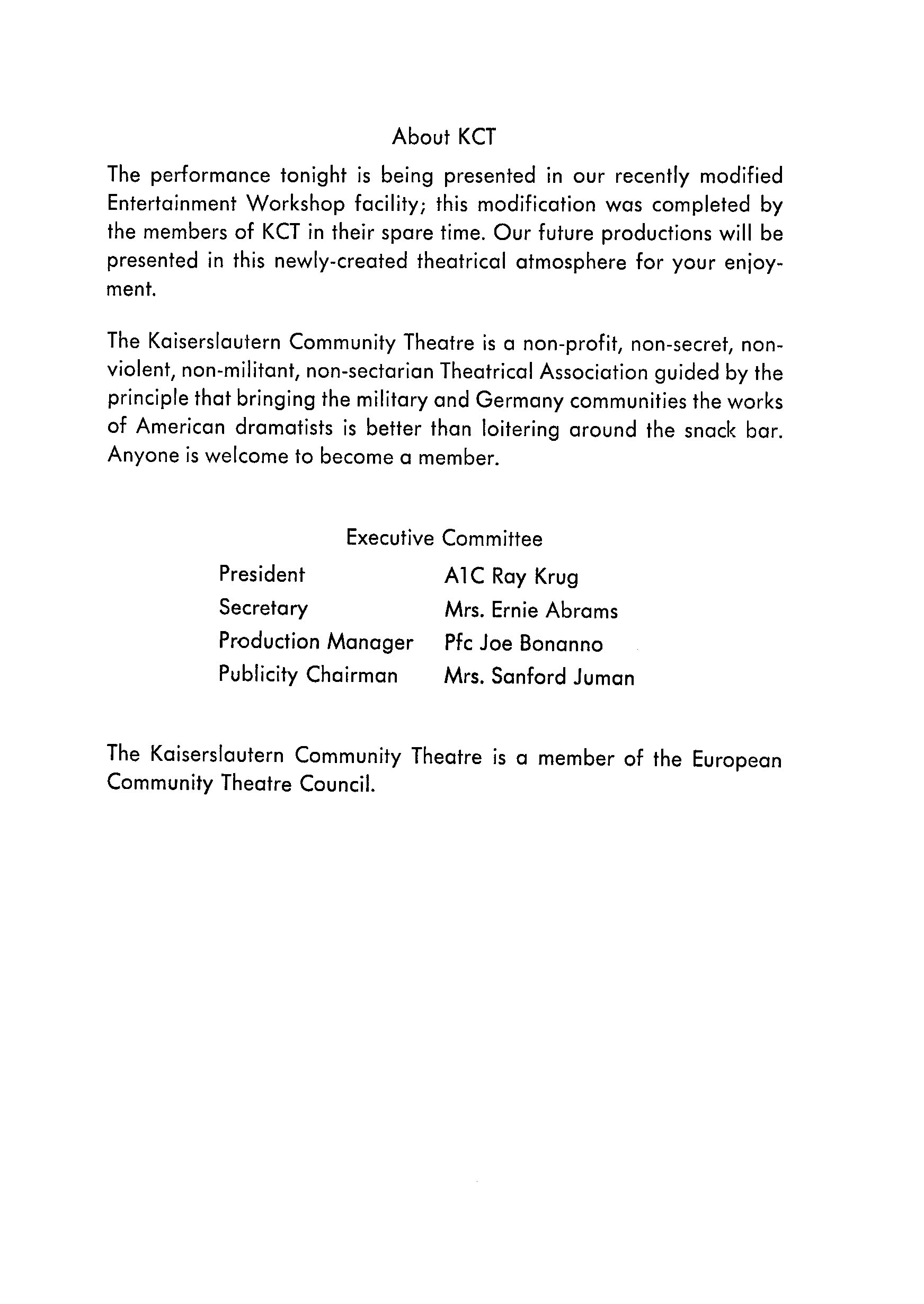

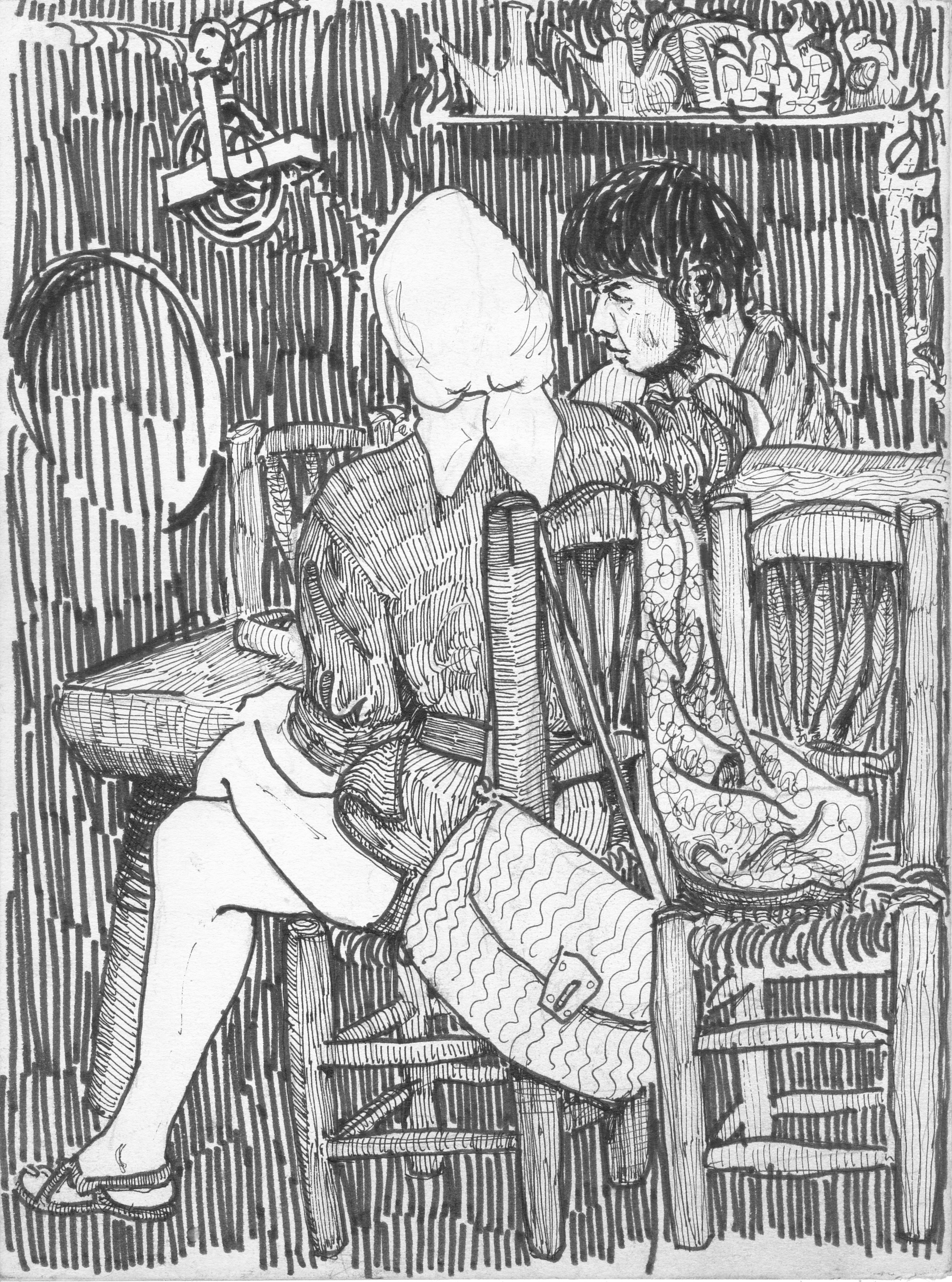

A Taste of Honey was written by an 18-year-old British girl,

Shelagh Delaney; it's about working class

people in the industrial north of England, interracial romance, mixed-race

babies born out of wedlock, gay people, alcoholic mothers, etc, pretty

gritty for its time. It was made into a film that sparked the whole British

New Wave (and the career of Rita

Tushingham), and the Beatles recorded the song too. Kind of

subversive for an Army base, but not surprising since Kaiserslautern

Community Theater describes itself as "non-profit, non-secret, non-violent,

non-militant, non-sectarian theatrical association". The people were a

mixture of all ranks, genders, sexual preferences, and races. And "military

courtesy" was checked at the door.

The mother and daughter in the play were mother and daughter in real life: Sandi Ramsey (listed as Mrs. Paul Ramsey on the program) and her daughter Connie (listed as Constance Asbury). The mother was bossy, controlling, and high-strung and was forcing Connie to act in the play, which made her miserable and a nervous wreck. Connie was the only girl I had a date with the whole time I was in the Army and all we did on the date was talk about her mother. Since I had a somewhat similar experience with my father, I was able to sympathize. I said just get the heck out as fast as you can, like I did. Who knows, maybe she joined the Army!

Being in a play while in the Army was tricky because you had to be in bed by 10:00pm lights-out bed check but the play ran until after that and it was pretty far away. For staying out late, some people used the old duffle-bag-under the covers trick but it rarely worked. I invented a better trick... Since our room in the barracks had 15-20 people, it would be easy to overlook if one of the beds was missing, especially if you rearranged the other beds so there was no gaping space. So I'd strip my bed, put the bedding in my wall locker, fold up the bed frame, and put it behind the wall locker. The OD (officer on duty who did the bed check) just looked to see if each bed was occupied, but never actually counted them, heh heh.

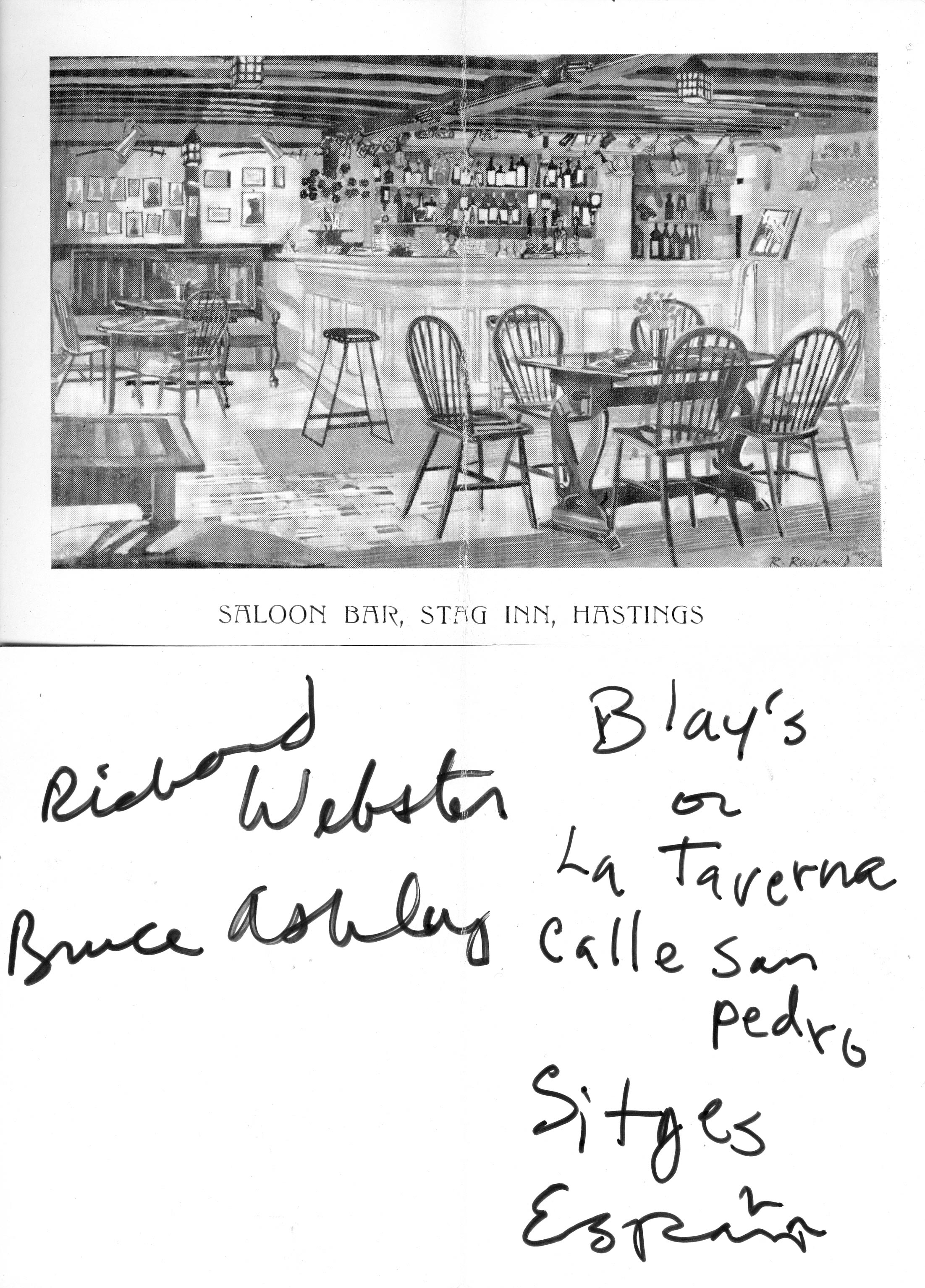

Sitges, Spain

|

| 1949 VW controls |

|

| 1949 Volkswagen (nicer than mine) |

|

| Guardia Civil |

|

|

| Sitges Spain 1964 |

|

| Sitges 1964 |

|

| British friends |

After Sitges

|

| NSU Prinz (not the same one) |

|

| Painting of me by Munn (now lost) |

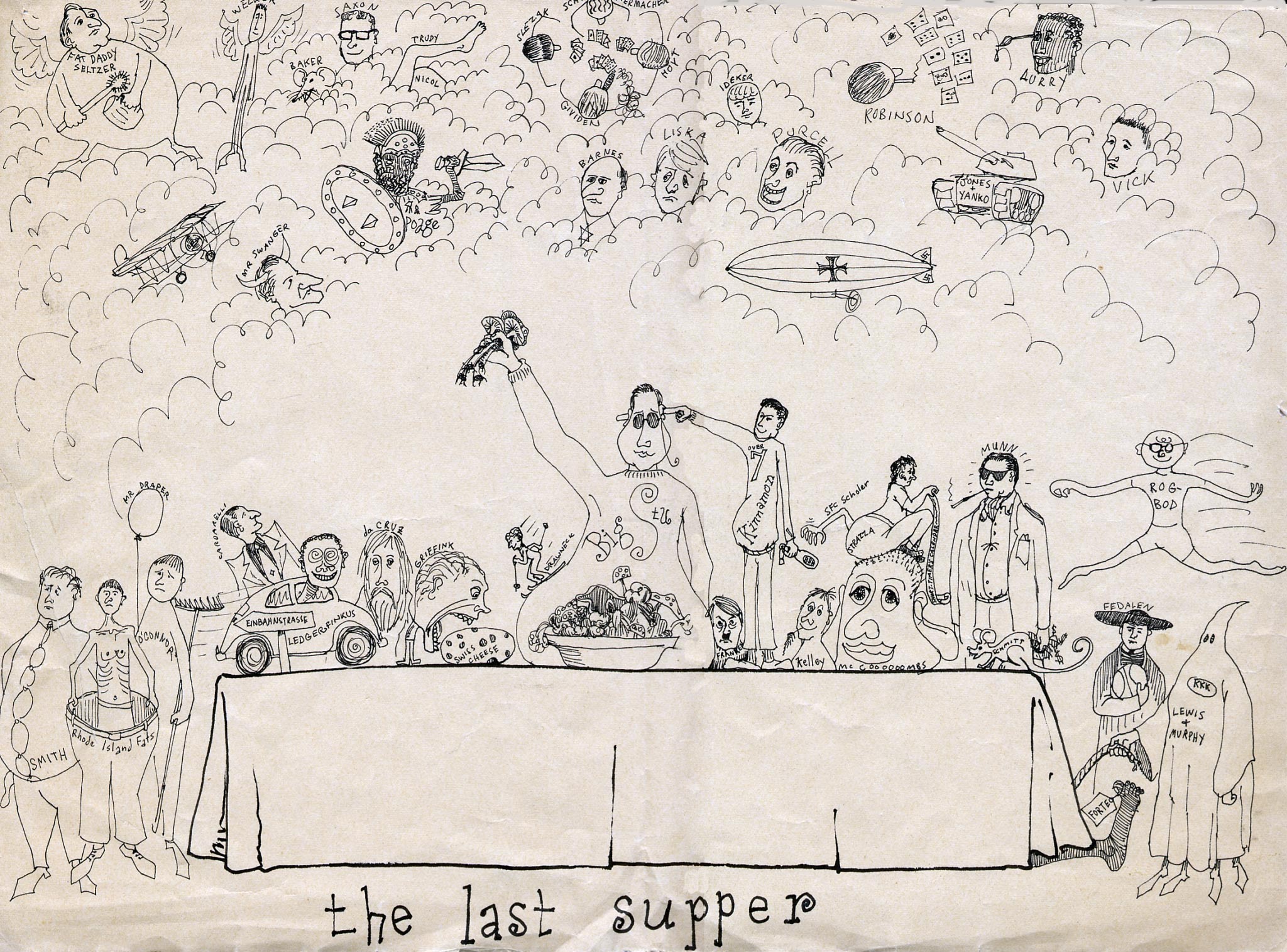

This guy, by the way, was a white guy from Bulawayo, Rhodesia, John Hugh Stuart-Munn, who had a degree in architecture at the University of Cape Town. He was active in the anti-apartheid movement and had been arrested so many times he had to get out so he came to the USA. But was drafted almost immediately. He said in South Africa they could hold you without charges for 180 days; for anti-apartheid whites, they'd turn you loose and then arrest you again as soon as you stepped on the sidewalk, over and over which happened to him I don't know how many times.)I spent their last week with them and they showed me their whole world, parties, bars, etc. A whole secret underground world. Then they were gone. I realized that, aside from Ken Nicol (next paragraph), they were the only ones who got sex on a regular basis, or at all. In February 1965 I wrote letters vouching for their fine qualities as workers and human beings. In the end, as Munn reported to me later, "We got General Discharges under Honorable Conditions, and were not reduced to lowest Enlisted Grade, so we got away almost scot-free and except for a slight stain on our reputations we are as good as the next man who served out his misery in full." He went straight to Berkeley where Stewart and Barnes were waiting for him.

|

| "Last Supper" by Munn |

|

| Munn by Barnes |

- 3rd Cavalry Regiment, Wikipedia, accessed 3 March 2020. Wherever the USA was stealing land from Indians or Mexicans, wherever it was invading countries that never posed any threat to the USA, the 3rd ACR was there. The only bright spots were that it fought on the Union side in our Civil War and it fought the Nazis in WWII.

- Blood and Steel – The history, customs, and traditions of the Third Armored Cavalry Regiment, Third Cavalry Museum, 2008.

- 3d Cavalry Regiment Museum, Fort Hood, Texas.

- Kaiserslautern Military Community hosts memorial to Father Emil Kapaun to be awarded Medal of Honor, US Army 21st TSC Public Affairs Office, April 5, 2013 (we lived an worked in Kapaun Barracks).

- Medal of Honor recipient and Korean War Soldier accounted for, US Army Public Affairs, 5 March 2021.

- 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, at USARMYGERMANY.com by Walter Elkins: 3rd ACR history and overview of each Squadron with photos (some used in this history, with permission).

Transfer to Stuttgart

|

| Patch Barracks Stuttgart-Vaihingen |

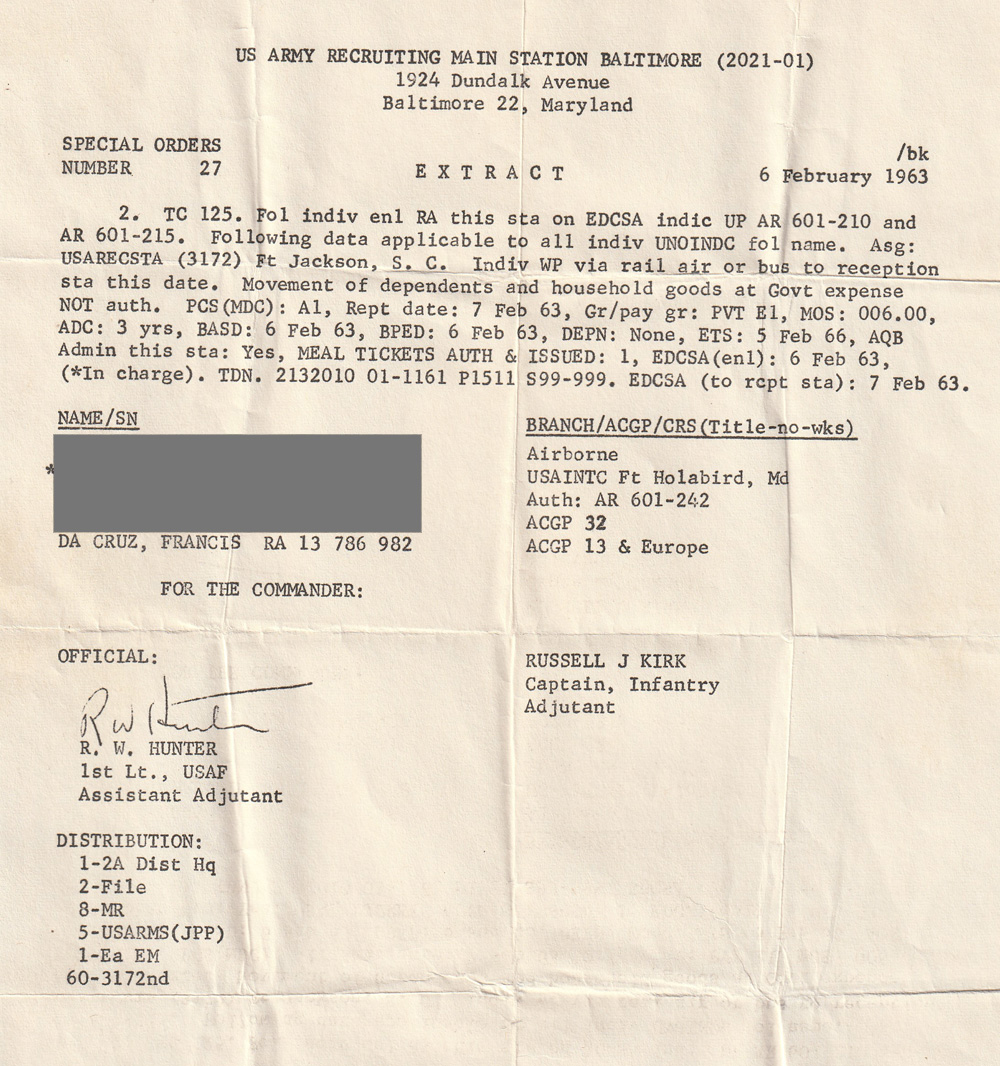

Side trip: Cutting orders

About "cutting orders"... You may have heard the term, but why "cut"? From the 1920s or 30s up through at least the 60s or 70s, military orders were indeed "cut". The first image at right is an Army order from 1963, the one sending me to Fort Jackson after taking the oath in Baltimore. If you click to enlarge it you can see it looks almost just like it came from a typewriter, but it didn't.

Anyway, when typing on paper and you hit a key, it shoots up the associated typebar, which whacks the ink ribbon, which presses the image of the character onto the paper (similar to a rubber stamp and inkpad). The result of typing is normally a sheet of paper with typewritten text on it. If you want extra copies you can use carbon paper, but there's a limit to how many legible copies you can get that way. If you need LOTS of copies, you can use either a mimeograph machine or a stencil machine. In the Army we had stencils (obviously there are more options nowadays).

A stencil is a long sheet of blue waxy stuff, typically 8½×18", that can be run through a typewriter — just like paper — but with a different result. When typing a stencil, the type bar whacks into the waxy stuff, punching (cutting) a hole in the shape of the letter; thus the orders are "cut". When you're finished typing you put the blue rubbery sheet around the stencil drum and then you turn the crank around and around to produce the desired number of paper copies (or if it's an electric machine, you set the number and push the Start button). The stencil machine forces ink through the cut-out character shapes onto the paper. Later, if you need more copies, you can make them from the same master (stencil). A military headquarters would typically have a room where dozens or hundreds of stencils were hung up to dry like laundry on a clothesline until they were no longer needed. You can find a more graphic description of a stencil machine (Roneo) on p.152 of the WWII historical novel Library Spy by Madeline Martin, Hanover Square Press, 2022.

The stencil business was just one aspect of Army orders. Another was that an order should be as short as possible, and this was done by abbreviating all sorts of common words and phrases as specified in the Army Abbreviations and Acronyms manual, as shown in the sample order: "Fol indiv RA this sta on EDCSA indic AR 601-210 and AR 601-215" (the following individuals enlisted Regular Army this station on Effective Date of Change of Strength Accountability indicated in Army Regulation 601-210 and Army Regulation 601-215); "all indiv UNOINDC" (all individuals unless otherwise indicated); "Asg: USARECSTA..." (Assignment: US Army Receiving Station..."); "Indiv WP via..." (Individual will proceed via...), etc etc. You can see a 1985 version of the manual HERE.

7th Army Headquarters, Patch Barracks, Vaihingen

|

| Bad Dürkheim Weinfest |

|

| Bad Dürkheim Weinfest |

|

| Camping out (Roger's VW) |

|

| Schiller College, Kleiningersheim, 1965 |

|

| Tübingen with pole boats |

|

| Stone from Dachau camp |

|

| Dachau ovens (Wikipedia) |

Berchtesgaden was where Hitler and his friends had lived only 20 years before. While we were there Roger and I climbed the Kehlstein [1800m] to the Eagle's Nest (which I had been to with my family when I was 14), it was the only time I used my expensive German mountain-climbing boots. We had no idea what we were doing and we nearly killed ourselves lots of times. We made it to the top somehow, had tea in the teahouse, but instead of climbing back down we took Hitler's elevator. I still have the boots but they no longer fit because my feet grew three sizes when I started running!

|

| Spätzle |

My first "computer" job

|

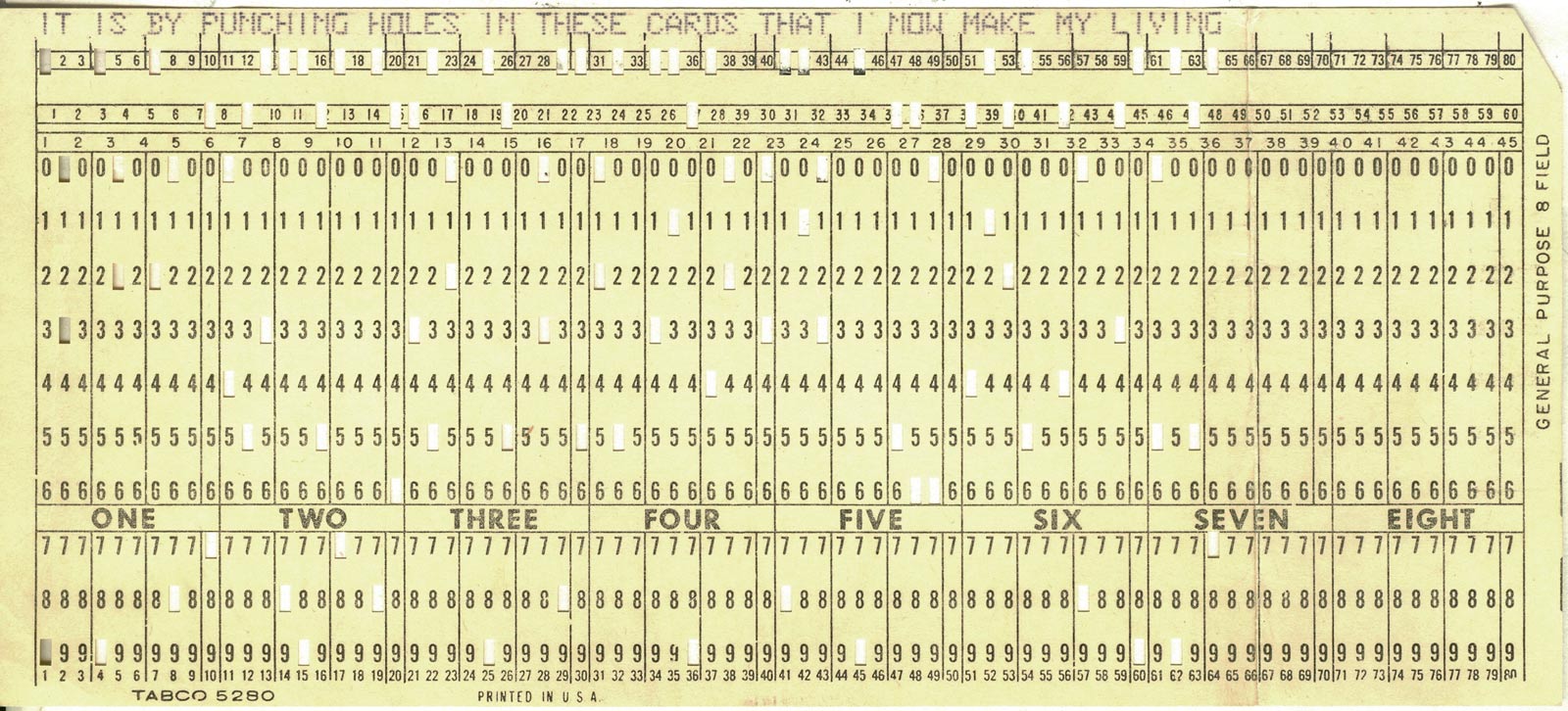

| Card punched by me at 7th Army CCIS in 1965 |

|

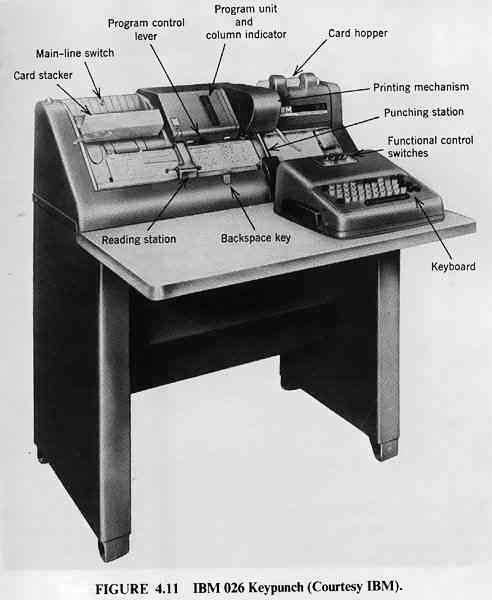

| IBM 026 Key Punch |

It's hard to believe that we had 12 E6's and 12 E7's, 3 Lt's and 2 or 3 WO to program a computer with JUST 8K of memory. The 1401 was programmed for MRS (Military Report System) in the field. Which was a simple sequential database on tape. 1 block for each report. Each Hq office would submit info in card format which was put to tape as input to MRS. We could hardly program anything with just 8K ram. Every report had to be the same format. No individual calculations. We were barnstorming one day and Jodie Powers wondered if we could somehow put 1 or 2K of code on the tape with each block of data. Then we could individualize each report. So I finally got it programmed and it work very well. We also programmed stuff for garrison work. I had all the conventional ammo in Europe. Spurling (because he spoke German) and I think Jerry Cook, had the marching orders program (in case of war). I don't remember the other projects. We went around to a lot of Battalion headquarters begging for work. I stayed in the Army for 20 years. Then worked as a Systems Programmer on the IBM 360/370 and others until I retired for good in 1996. I was fortunate to learn computer programming in the Army.

|

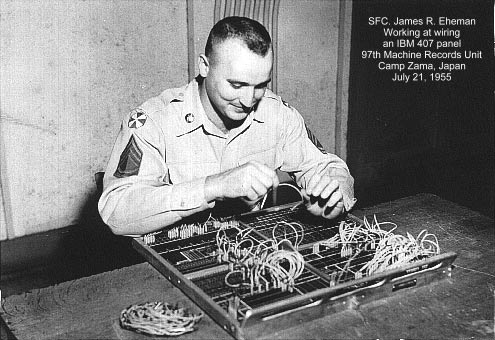

| Wiring a plugboard (not me) |

|

| Plugboard in place |

Anyway I became a wizard at key punching, the fastest ever, because I was a 120wpm touch typer and I figured out how to make program cards for the IBM 026 (i.e. I RTFM'd). I forget what Roger was doing, I think he may have been a driver for our company commander. Finally they sent me (but not Roger) to Computer School, which was a collection of quonset huts in the forest outside Orléans (France), where we learned to program everything BUT computers! Mainly "unit record" equipment (that operate on punch cards): sorters, duplicators, collators, interpreters, tabulators, and accounting machines: the big grey mechanical iron boxes from before there were what we consider to be computers today (Von-Neuman architecture, stored program, etc). The programming was done by sticking jumper wires into plugboards; see my computing history site for details if you're interested (look for Tabulators and the IBM 407).

|

|

| Me in Stuttgart barracks 1965 |

|

| Me in Stuttgart barracks 1965 |

|

| Enjoying a unit picnic 1965 |

| * | Lee Miller's War, edited by Antony Penrose, Thames & Hudson (2005). |

Paris

|

| An Olympia Press book 1960s |

|

| Beatniks under Pont Neuf 1965 |

|

| Me at Paris bookstall on the Seine 1988 |

Race and Integration in the Army of the early 1960s

"The army of the 1950s was America's most racially and economically egalitarian institution, providing millions with education, technical skills, athletics, and other opportunities" —Brian McAllister Linn, Elvis's Army[9].

|

| Fort Gordon, Georgia, unit 1960s |

(Drug use and Black Power… I saw no drugs the whole time I was in the Army, and there was only one Black guy in my unit who was openly hostile to white people. Things changed pretty fast just after I got out.)

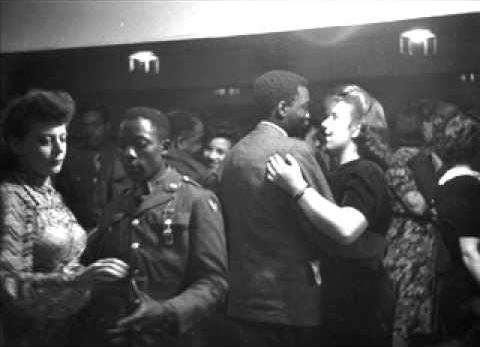

I read an eye-opening book in 2016, "GIs and Fräuleins" by Maria Höhn[2]. It seems Truman's 1948 order to integrate the armed forces was met with massive foot-dragging and as late as 1952 most units, including those in Germany, were still totally segregated. Apparently there was a lot of racial conflict within the Army up until about 1960. White GIs would go into town and demand that their favorite bars put up big signs saying "White only, no colored". Other bars took advantage by putting up "Colored only" signs. This was against German law but they did it anyway, so effectively there was segregation in the small towns around Army bases (but not big cities like Frankfurt), and the Army did nothing to discourage it. Germans justified it by saying they were only doing what the Americans did. The off-base hostility reached such heights that there was an all-out race war in Baumholder in 1955 — gun battles in town between Black and white troops with fatalities — and several others in Kaiserslautern in 1956-57, only 6-7 years before I arrived there in 1963.

|

| Little Rock, Arkansas, 1957 |

|

| German dance club 1960s[2] |

|

| Jutta Hipp about 1950 |

I went through the Army with a couple guys from the Alabama outback, one white and the other black. They had grown up in the same little town and had never spoken to one another, but once they found themselves in the Army together they became inseperable (I remember on long bus or truck rides, they would sleep cuddled up together). At the end of three years, about to go back home, they told me they had to say goodbye to each other forever.

- MacGregor, Morris J., Integration of the Armed Forces 1940-1965, Office of Military History, United States Army, Washington DC (1981).

- Höhn, Maria, GIs and Fräuleins - The German-American Encounter in 1950s West Germany, University of North Carolina Press (2002).

- Lemza, John W., American Military Communities in West Germany - Life in the Cold War Badlands, 1945-1990, McFarland & Company (2016).

- Dewey Arthur Browder, The Impact of the American Presence on Germans and German-American Grass Roots Relations in Germany, 1950-1960, Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College PhD dissertation (1987), 274 pages.

- Grossman, Victor, A Socialist Defector — From Harvard to Karl-Marx-Allee, Monthly Review Press (2019). Defections from East to West were highly publicized; defections in the opposite direction were hushed up but I was in a position to hear about them and this book confirms it.

- Adams Earley, Charity, One Woman's Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC, Texas A&M University Press (1989). The experiences of the first Black women in the US Army.

- Victor Grossman, "African Americans in the German Democratic Republic", in Larry A. Greene and Anke Ortlepp, Germans and African Americans: Two centuries of Exchange, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson (2011).

- Damani Partridge, "Exploding Hitler and Americanizing Germany", in Larry A. Greene and Anke Ortlepp, Germans and African Americans: Two centuries of Exchange, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson (2011).

- Brian McAllister Linn, Elvis's Army, Harvard University Press (2016).

- Oliver R. Schmidt, Afroamerikanische GIs in Deutschland 1944 bis 1973: Rassekrieg, Integration und globale Protestbewegung, doctoral dissertation, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, Münster (2010, copyright 2013). Available in print from AbeBooks.com.

- Aaron Gilbreath, The Brief Career and Self-Imposed Exile of Jutta Hipp, Jazz Pianist, This Is: Essays on Jazz, Outpost19, https://longreads.com, August 2017 (accessed 16 March 2022)

- Marc Myers, Jutta Hipp in Germany: 1952-'55 and Jutta Hipp: The Inside Story, jazzwax.com (accessed 16 March 2022).

- Hans Jürgen Massaquoi, Destined to Witness: Growing Up Black in Nazi Germany, Harper Perreniel (1999).

- Exorcising the Ghost of Robert E. Lee, Brent Staples, New York Times, 27 April 2023.

- Höhn, Maria, and Seungsook Moon, Over There: Living with the U.S Military Empire from World War Two to the Present, Duke University Press (2010). GIs and the women of West Germany, Korea, Japan, and Okinawa.

Consciencious Objecting

"Every war already carries within it the war which will answer it. Every war is answered by a new war, until everything, everything is smashed." —Käthe Kollwitz, Nordhausen, Germany, February 21, 1944[1]

|

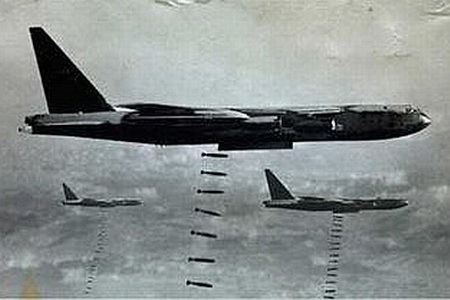

| Bombing Vietnam 1965 |

|

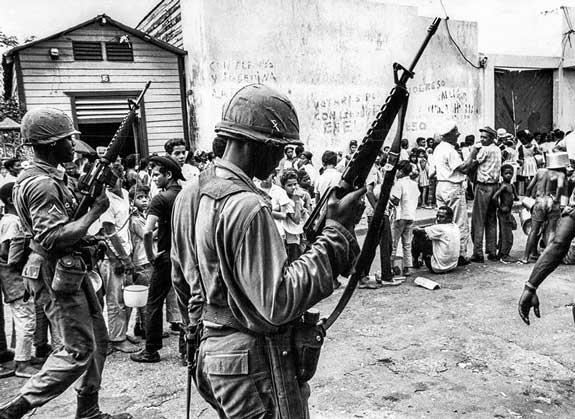

| Dominican Republic invasion 1965 |

When I got back to Stuttgart I had access to all the Army Regulations where I worked, and one day while reading through them I discovered an obscure paragraph in the then-current version of AR 635-20, "Active Duty Enlisted Administrative Separations", that allowed for somebody already in the Army to become a consciencious objector and apply for a discharge, and I did that because I did not want to be put in a position where I would have to kill people who only wanted to be left alone (or to help others kill them by working in a support role). The regulation stipulated that the only valid basis for conscienscious objection was religious belief, so I had to write the application that way. To do this I had to get a Bible and hunt through it for the good parts (what Jesus said to do and not to do) — no Google in those days! As noted elsewhere, this caused my grandfather no small amount of consternation, since he was an implacable foe of all forms of organized religion, despite (or because of) having spent his early years as a Catholic priest. If you want to read the application, there's a semi-legible PDF here. Rereading it now, 50-some years later, I can see how he might have been gotten the wrong impression.

Nobody in my chain of command had ever seen such a thing before and it took them months to figure out what to do with it; it went all the way up to the Pentagon. In the meantime AR 635-20 said I could not be required to do anything against my "professed beliefs", which I interpreted to include carrying a gun and saluting, which resulted in quite a few comical moments, and they couldn't hassle me for subscribing to left-wing and counterculture journals like Liberation magazine and Evergreen Review.

Once I walked right past a General, looking him in the eye, without saluting; he didn't say a thing. On the other hand, once I did the same thing to a pipsqueak 2nd Lieutenant and he went ballistic like in a Warner Bros. cartoon and started screaming "Post! Post!" in his high squeeky voice, which was some order he must have learned at lieutenant school but I had no idea what it meant, so I just ignored him and walked on.

Normally the Army in those days was pretty informal, it wasn't snapping to attention and saluting and Rah Rah America. I don't remember anybody I knew, NCOs and officers included (except my company commander), giving me a hard time about my CO application. Once on maneuvers in the outback of Schwaben, my platoon was sitting around a campfire at night (campfire = burning gasoline in a #10 can) roasting C-rations and drinking beer and we got to talking about the war in Vietnam. My platoon sergeant (picture him as the actor Brian Dennehy) was a Korean War combat veteran and it turned out that the war had disgusted him; he said he admired me for what I did and wished he had done the same thing. Some other guys in my unit followed my lead and also applied for CO status; I did the paperwork for them.

On the other hand… There were two Hawaiian guys in my unit, Akino and Barrios. They were straight out of the central casting: fun-loving, gentle, playful, always in a good mood, always horsing around, not a mean bone in their bodies. Off duty they wore Hawaiian shirts, sang Hawaiian songs and played ukuleles — they had Martins and they could do a lot more than just strum them. Here is a piece they taught me, "Sushi" (if the link goes bad, look up "sushi ohta-san"):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w2f7kyJA0SY

When the Vietnam war exploded in 1965, I was totally shocked when Akino and Barrios volunteered to be transferred to the 25th (Hawaiian) Infantry Division to fight in Vietnam. I said, What do you have against the Vietnamese??? Akino, at least, was Asian (it's the Hawaiianization of a Chinese name). They couldn't explain it, they just wanted to get away from the haoles and be with their own people. I tried to convince them not to, but off they went. Searching The Wall (www.vvmf.org) I'm glad to see that neither of them was killed. (Later I read about the history of the Hawaiian divisions in James Michener's Hawaii book[2] and understood it better. But still...)

Just a couple weeks before my hitch was up, my CO application came back denied. My immediate commanding officer had recommended disapproval (because he didn't like it), but all the higher level commanders (e.g. of the 7th US Army) recommended approval, all the way the Pentagon, where the Secretary of the Army, Cyrus Vance, wrote that the application was "not favorably considered", no explanation given. But by then I was already short, i.e. on my way out. So I served my full hitch and since I hadn't broken any laws or Army Regulations I have an honorable discharge.

- The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz, Northwestern University Press (1955).

- James Michener, Hawaii, Random House (1959).

For the record...

As of 2017, there were 58,318 names on the Wall (the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in the US National Mall in Washington DC): military men and women who were killed in Vietnam (National Park Service). But "for many Vietnam veterans, the horrors of war manifested itself into post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Others suffered from Agent Orange-related illnesses including: Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, and cancer" (Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund) ... "Agent Orange is taking a huge toll on Vietnam Veterans with most deaths somehow related to Agent Orange exposure. No one officially dies of Agent Orange, they die from the exposure which causes Ischemic Heart Disease and failure, Lung Cancer, Kidney failure or COPD related disorders" (Veterans Administration) ... "However, the wall does not document any names of the estimated 2.8 million U.S. vets who were exposed to the poisonous chemical while serving and later died": Forbes ... "The Monsanto Chemical Company reported that the TCDD in Agent Orange could be toxic as early as 1962. The President's Science Advisory Committee reported the same to the Joint Chiefs of Staff that same year. Studies from 1954 onward confirm the toxicity of both herbicides used in Agent Orange": Military.com.It was President Kennedy who gave final approval to "Operation Ranch Hand", the massive effort to defoliate the forests of Vietnam, Cambodia. and Laos with the toxic herbicide known as Angent Orange. The U.S. Air Force flew nearly 20,000 spraying sorties from 1961 to 1971 under the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon Administrations: Into the Wind: The Kennedy Administration and the Use of Herbicides in South Vietnam, Georgetown University (2012).

Besides American and allied soldiers (e.g. Australian), approximately 400,000 Vietnamese died due to a range of cancers and other ailments caused by Agent Orange, and approximately 4.8 million Vietnamese people were exposed to Agent Orange: Wikipedia.

And in addition to all those directly exposed are their children and grandchildren, who have a much higher rate of birth defects than the general population, including mental retardation, cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, deafness, missing limbs/fingers/toes, heart defects, blindness, and on and on: birthdefects.org.

Total death toll so far: more than six million (3.8 million war casualties + 2.8 million delayed-action "aftermath" deaths including not only toxins but also unexploded munitions left behind at war's end).

- Vietnam War casualties, Wikipedia (accessed 26 December 2023)

- Vietnam War | Background, Casualties & Statistics, Study.com: "The Vietnam War death toll is estimated to be around 3.8 million casualties in total."

- Home before Morning: The Story of an Army Nurse in Vietnam, Lynda Van Devanter, University of Massachusetts Press (1983, with an afterword from 2001). Perhaps the best book ever written about the Vietnam War. The author was a combat nurse who served in Pleiku and Qui Nhon, and — coincidentally — had been a schoolmate of mine at Yorktown HS in Arlington VA, 1961-62 (but I didn't know her). She returned with severe PTSD but eventually was able to build a life around organizations that helped returning veterans (especially combat nurses) overcome their nightmares and become functional again. She died in 2002 from the delayed effects of exposure to Agent Orange and other deadly chemical agents used by the US forces.

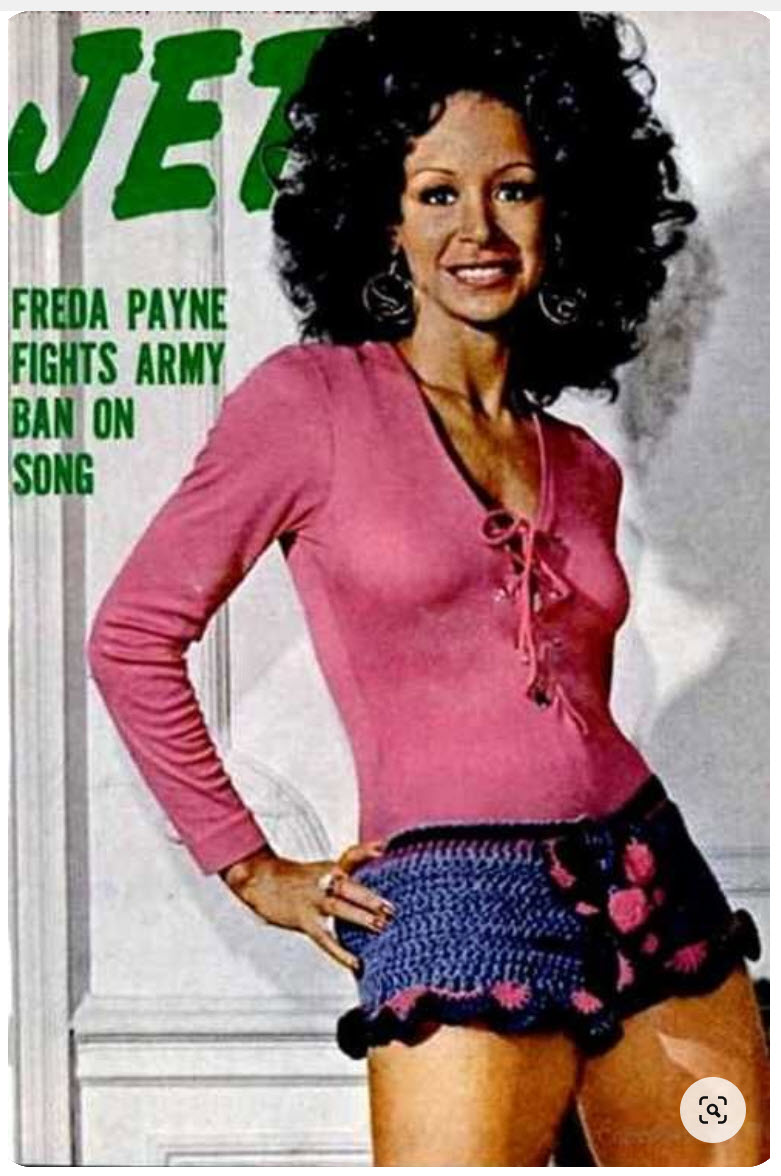

Bring the Boys Home... Appreciating Freda Payne

|

| Click image to enlarge; click HERE to read article. |

Elsewhere in this history I describe working at the Armed Forces Network in Germany in the early 1960s. I had great respect for AFN for reasons I go into in the Frankfurt chapter, but apparently President Nixon ordered AFN not to play this song. But Freda says, "Ironically, the soldiers did hear it. And you can’t believe how many have come to me and said it was the song that got them through the Vietnam War."[5]

- Bring the Boys Home (Youtube).

- Band of Gold, Freda Payne's 1970 #1 hit (Youtube).

- "Freda Payne Fights Army Ban on Song", JET Magazine, October 1971.

- "Freda Payne Recalls Her Anti-War Song Banned by US Armed Forces Radio in 1971", Roger Friedman, Showbiz 11, 2 November 2021.

- Freda Payne autobiography, Band of Gold, a Memoir, with Mark Bego, Yorkshire Publishing (2021).

- Bring the Boys Home, Wikipedia, accessed 28 November 2023.

- Bring the Boys Home, Lyrics (songfacts.com).

Getting out...

Being short means that you no longer have to do your job because you have countless offices to go to and get various things checked off. Short-timers carry a clipboard with all their checkout forms and nobody bothers them, so in effect their last week or two is like a vacation. But even when you're not short, a good trick is: whenever you go outside, carry a clipboard and walk fast, everyone assumes you're doing something important and official so they won't hassle you.

|

| USNS Geiger |

|

| Geiger deck and lifeboats |

|

| Bunks in the hold |

They let us up on deck a few times when the weather was good and there were dolphins leaping and playing alongside. When we were were almost in NY, there was a huge storm with 50-foot waves and near-hurricane winds and the Geiger was bobbing around like cork. I was so sick I found a way to get out of the hold and onto the fantail, where there was a little balcony cut into the stern of the ship. I held on for dear life to the railing and puked my guts out while at one minute I was looking up at a wave as tall as a mountain, and the next minute the ship was perched on top of it, and the next it slid all the way down into the trough, while the vomit blew back into my face. It didn't matter, I was soaking wet, icing up actually, but at least I was breathing good air. In four crossings, this was only time I ever was sick.

We landed February 2, 1966. Looking at a map I realized just now for the first time that we came in through Long Island Sound. I know that because I remember looking up and seeing a sign that said "125th Street". That must have been when we were going under the Triborough Bridge. We landed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard (which was also a naval port throughout its history) and were bussed from there to Fort Hamilton where I got my walking papers and that was the end of the Army.

I realize that I owe a lot to the Army. I was pretty worthless before I was in it, and it taught me some valuable things. Like, if you have to do something, just go ahead and get it over with, no matter how awful; nothing lasts forever. And like, don't let big messes accumulate, always be cleaning things — "Clean as you go"; it was a good habit to get into that I never had before. Or, do things for yourself instead of expecting somebody else to do them for you. But being in the Army didn't teach me how to get along with and appreciate all different kinds of people from all different places, because I already learned that in Frankfurt — which was also the Army — but for most other people it's an important lesson.

The Army of the early 1960s was almost a microcosm of life itself. It did practically everything to sustain itself except grow food. So we learned the great variety of tasks required in a society, and we did most of them ourselves: cleaning house, yard work, preparing food, picking up trash, taking garbage to the dump, maintaining equipment and vehicles, operating hospitals, schools, stores, and radio stations (that had no ads!), ... Once I even spent spent a few days at Fort Knox building a concrete staircase up a hill. This gave us some respect for people in real life who made their livings in those ways: sanitation crews, cooks, cleaners, mechanics, teachers, nurses, doctors, disk jockeys, truck drivers, construction workers... Conversely, the Army did not include any of our 21st-century gods: hedge-fund managers, commodities traders, arbitrageurs, leveraged-buyout specialists, stockbrokers, portfiolio managers, corporate raiders, vulture capitalists, or anyone else who could become obscenely wealthy without actually doing any productive work.

Kids today grow up in little bubbles as society becomes increasingly compartmentalized by race, religion, social class, social media, and cell phones. I wish the peacetime Army — and the draft — still existed, or something like it — for example, the CCC camps of the 1930s. A few years in a setting like that is a great experience for kids right out of high school: living and working with diverse people from all over the country, learning skills, learning to depend on other people and to be dependable, learning respect for others. Speaking for myself, I was definitely not ready for college after high school, but after the Army I was. I knew how to work.

Obviously I don't favor a draft if it is used to send people to wars of conquest, except insofar as it might spark another 1960s-magnitude antiwar movement. But some kind of compulsory national service would be an effective antidote to the anomie and aimlessness of 21st-Century American young people, especially if the service was focussed on doing work that was needed (e.g. to fix the infrastructure, save the planet) and helping people who need help, like in the original New Deal.

- Fifty Years Ago, Frank da Cruz, The Veteran, Vietnam Veterans Against the War, Vol.46., No.1, Spring 2016 (I'm not a Vietnam veteran but the organization is for all Vietnam-era veterans).