The often contested terrain of queer and gender studies has long been the rooted in the body. Although various disciplines such as art history and archaeology have begun to look at representations of the body and bodily adornments, objects and material culture in their own right have remained comparatively untouched by the probing questions of queer theorization and histories of sexuality. Using Crisco as a case study, I’d like to explore the productive intersection of thing theory and queer theory, or the queerness of things, and suggest that things as discursive and material formations be treated as “sexed” and equally caught up in the production and subversion of sexual identities. It is the contention of this essay that fooling around with messy and slimy things such as Crisco may not only tell us more about the construction of gender, family, and sexuality but also gives us more opportunity to queer them.

The term queer, like Crisco, is a somewhat slippery thing. Queer arose as a way of acknowledging and assessing difference without needing first to define that difference in the reductive fiction of identity politics.[1] Building on the work of gay and lesbian studies and third-wave feminism in the late 1980s, queer theorists have attempted to challenge essentialist notions of homosexuality and heterosexuality, asserting an understanding of sexuality that emphasizes shifting boundaries, ambivalences, and constructions that change depending on historical and cultural context. Queering then is an activity of questioning, a critical practice of turning taken-for-granted tropes and making strange the assumed naturalness of things.

Thing theory, in its various manifestations, might also be said to be queer or at least attempts to queer normative interpretations and methodological practices in various disciplines. Appadurai’s injunction for a methodological fetishism that calls for an abnormal traffic in information, one in which the norm to be deviated from is the theory that only humans can produce meaning. Similarly, Bruno Latour’s and Actor Network Theory’s notion of radical symmetry queer the assumed hierarchies and binaries of subject/object and human/nonhuman. Thing theory then offers a somewhat queer critique of the supposed primacy of the subject. More importantly, however, thing theory forces us to extend beyond the body to encompass material culture and things. Following such scholars as Donna Haraway and Bruno Latour, we might see sexuality as an assemblage that includes both bodies and things, produced through the continual fragmentation, dispersal, and reconfiguration of person by their extension into material culture. Thing theory challenges the centrality of the body in the production of queer and normative identities and provide a critical analysis of present material culture studies. Accordingly, Crisco’s own slippery and sexed materiality might allow us to explore the ways in which things can slide between identities and in doing so, are able to queer certain norms.

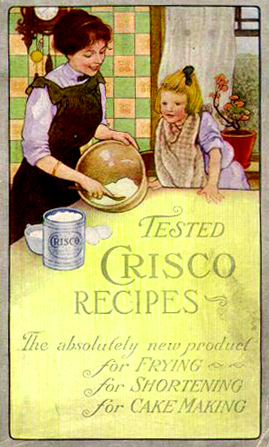

Crisco was introduced by Procter & Gamble in 1911 and, according to the companies website, not only provided an economical alternative to animal fats and butter, but “revolutionized the way food is prepared and the way it tastes.” It was the first solidified shortening product made entirely of vegetable oil, the result of partial hydrogenation, a relatively new process that produced shortening that would stay in solid form at room temperature for two years without turning rancid. Upon its introduction to the market, Crisco led to the creation of new cookbooks and cooking methods. This cookbook, created to accompany the introduction of Crisco into American homes, helped launch an educational campaign to market Crisco to homemakers who were familiar with lard and butter cooking methods, but new to the use of vegetable shortening. In addition, in the first two decades of the twentieth century, Procter & Gamble hired home economists to lead cooking schools around the country, teaching homemakers how to use the all-vegetable shortening. These cooking schools helped boost the image of home economists at a time when the home economy profession was first being recognized.

The first print advertisement for Crisco was released in popular women's magazines in January 1912. This original Crisco ad focused on the benefits of Crisco all-vegetable shortening over animal fats and butter. As the ad points out, "You can fry fish in Crisco, and the Crisco will not absorb the fish odor! You can then use the same Crisco for frying potatoes without imparting to them the slightest fish flavor.” Additionally, Crisco could be heated at significantly higher temperatures than lard, without burning or giving off smoke. Less Crisco would be absorbed by the food, thereby making it more economical. The ad encouraged homemakers to try Crisco, "and realize why its discovery will affect every family in America." Indeed, during the early 20th century, Crisco was but one of many new products and technologies that drastically changed the home and the American family. Filled with electrical appliances and brand-name products, many households could and did dispense with servants. As historian Glenna Matthews has argued, this all added up to immense changes in cookery, in the American diet, and the structure of the American family.[2]

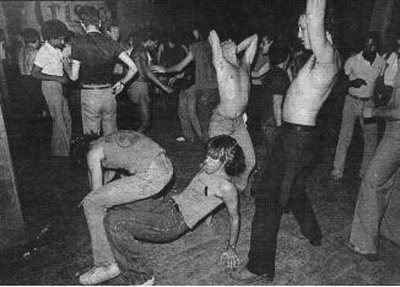

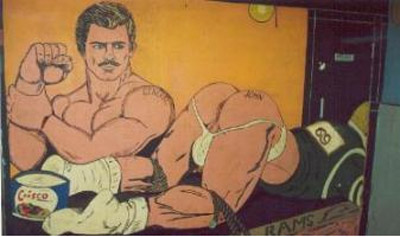

Thus, upon its inception, Crisco would seem to have been a highly sexed object, bound up with the formation of certain notions of heterosexual familial relations. Yet, to assume that Crisco functioned solely within the framework of heteronormative sexuality would only reinforce sex and gender binaries. In fact, Crisco was also regularly used by queer subcultures, joining Vaseline as one of the most popular forms of lubricants for anal sex. In fact, during the first decades of the 20th century, Vaseline was so popular that a quarter-mile long section of Central Park, known as a cruising ground, was aptly nicknamed “Vaseline Alley.”[3] By the 1970s, however, Crisco and other vegetable shortening had become the most widely used lubricants. The first-edition of The Joy of Gay Sex, published in 1977, declared, “Vegetable shortening may be the best lubricant, since it is not only greasy but also digestible”[4] Such a statement perhaps gives new meaning to the companies boastful declarations that “Its digestible” and “Crisco has been making life in the kitchen more delicious for years.” Similarly, in the 1978 sex manual The Advocate Guide to Gay Health, Crisco even earned an entry in the book’s index. Discussions of the shortening’s use as an anal lubricant indicate its popularity, with statements such as: “The lubricant, typically the cultic Crisco, must be copious.”[5] In fact, Crisco was so synonomus with gay sex that discos and bars around the world took on the name, such as Crisco Disco in New York City, which was one of the premiere clubs during the 1970s and early 1980s. Other clubs or bathhouses, such as Club Z in Seattle, even featured murals with Crisco. Thus, Crisco was conversely also one of many things that led to the formation of gay identities during the 20th century.

David Halperin has suggested that queer “describes a horizon of possibility whose precise extent and heterogeneous scope cannot in principle be delimited in advance.”[6] I’d like to suggest that Crisco, in its own materiality and interaction with humans, offers just that, queer possibilities or affordances that were not conceived or “delimited in advance” by its original producers. JJ Gibson’s concept of the “affordance” perhaps offers a framework through which we can understand how different registers of meaning can coexist in our perception of things and their materials: how Crisco, on the one hand, might be used for frying, while on the other, for fucking. Gibson had suggested that we do not perceive the function of things in the abstract by itemizing their particular qualities, but we perceive their “affordances”—what they particularly allow us to do. What a thing means to a user, and what it is useful for, is simultaneously a consequence of the expectations the user brings to the interaction with the thing and its “invariant” properties. As Gibson puts it, an affordance cuts across the objective/subjective dichotomy. Although Gibson illustrates his ideas by reference to our interactions with the given physical environment, the invariant qualities of man-made objects also constitute affordances.

So, is it possible that certain things or objects have inherently queer affordances? Or, is the very idea of affordances something that allows one to queer? One of the main reasons, besides its edibility, that allowed Crisco to be used as a lubricant was its viscous, tactile quality, almost slimy, especially in its shortened form. In fact, various websites and books on gay sex suggest that it is one of the few lubricants that doesn’t wear off, its slippery but also sticky. Yet, what exactly is this quality? In Being and Nothingness, Sartre asks, "What mode of being is symbolized by the slimy," and posits that "the slimy reveals itself as essentially ambiguous because its fluidity exists in slow motion; there is a sticky thickness in its liquidity.” Slime, in other words, is neither liquid nor solid, but something in between, something that defies or escapes both categories. In the midst of liquid or in the presence of a solid, we are always aware of our facticity, our own solidity, but this is not so in the case of the slimy. Slime is "an aberrant fluid," the "revenge of the In-itself," in that there is always the feeling that it might absorb us, that we will not be able to get rid of it or escape it—"only at the very moment when I believe that I possess it, behold by a curious reversal, it possesses me," Sartre writes. Thus, for Sartre sliminess itself is a somewhat queer or deviant material for it makes one’s relationship to the world strange by denying the primacy of the self.

Ultimately, it was the mutual relationship between object, persons, and certain contexts that established Crisco’s affordances or what Carl Knappett has referred to as the sociality of affordances.” Yet, it was also it oiliness that prohibited or no longer afforded its use during sex during the 1980s and after. The discovery that the AIDS virus can be transmitted during sexual activity drastically changed people’s sexual practices, and the use of the condom increased strikingly, in a large part due to gay right activists and safe sex education. In 1985, a study showed that sexual activity was reported to have declined by 78 percent since hearing about AIDS. The frequency of sexual episodes involving the exchange of body fluids and mucous membrane contact declined by 70 percent, and condom use during anal intercourse increased nearly 20 per cent.[7] Yet, during the same time, it was learned that oil-based lubricants such as Crisco, petroleum jelly, and some hand lotions, weakened latex condoms thus increasing the chances of breakages and tears and the chance of infection. In fact, a study released in 1988, showed that as little as sixty seconds' exposure of commercial latex condoms to certain oils caused approximately 90% decrease in the strength of the condoms.[8] As a result, the use of Crisco and other oil-based lubricants drastically declined in the following years. In Mourning and Militancy, Douglas Crimp, a art critic and historian, mourned over the loss of not only loved ones, but also the ideal of perverse sexual pleasures:

Alongside the dismal toll of death, what many of have us lost is a culture of sexual possibility: back rooms, tea rooms, bookstores, movie houses, and baths; the trucks, the pier, the ramble, the dunes. Sex was everywhere for us, and everything we wanted to venture: golden showers and water sports, cocksucking and rimming, fucking and fist fucking. Now our untamed impulses are either proscribed once again or shielded from us by latex. Even Crisco, the lube we used because it was edible, is now forbidden because it breaks down the rubber. Sex toys are no longer added enhancements; they’re safer substitutes.[9]

Thus, AIDS changed the possibilities for sex, the affordances of various places and things. Crisco’s ultimate demise as lubricant for anal sex was due to its own physical properties—the very oiliness that made it great for cooking and sex—and its interactions with other things—condoms, AIDS, and humans.

In its crossing of homoeroticism and domesticity, of cooking and fucking, Crisco manages to slide between and topple the traditional divide between men’s work and women’s work, between machismo and housewifery, between heterosexual and homosexual. Looking at such objects, their affordances, and the multiple interactions between human and other nonhumans can allow us to queer normative assumptions and practices. However, I’d also like to suggest that even without the help of critically queer scholars, things have the potential to queer on their own, to not only subvert but also produce identities. Yet, today, Crisco can only perform its queer work if its story is told. The production and use of objects demand connections, between persons and between different materials, individual bodily practices, and group actions. As such, they may reveal the complex and changing relations between people, places, and things. The production of personal identity is one of continual performance enabled through the continued changing relations enacted between people and materials. The case of Crisco highlight that things link the sexualities of the assemblages in which they figure to processes that are supportive but also sometimes subversive of hierarchies, generating new possibilities, new sexualities, and future identities.

[1] See, for example, Judith Butler, "Critically Queer," Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of "Sex" (New York: Routledge, 1993), 223-42; the "Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities" issue edited by Teresa de Lauretis of differences 3 (1991); and Fear of a Queer Planet , ed. Michael Warner (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1993).

[2] Glenna Matthews, Just a Housewife: The Rise and Fall of Domesticity in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989)

[3] George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 182.

[4] Charles Silverstein, The Joy of Gay Sex: An Intimate Guide for Gay Men to the Pleasures of a Gay Lifestyle (Outlet, 1977).

[5] R. D. Fenwick, The Advocate Guide to Gay Health (Los Angeles: Alyson Publications, 1978).

[6] David Halperin, Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography (New York: Oxford University Press,1995), 62.

[7] JL Martin, “The impact of AIDS on gay male sexual behavior patterns in New York City” in American Journal of Public Health. 1987 May;77(5):578–581.

[8] B Voeller et al., “Mineral oil lubricants cause rapid deterioration of latex condoms” Contraception. 1989 Jan;39(1):95–102.

[9] Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy”, October, Vol. 51. (Winter, 1989), 11.