FOREWORD

THEATER is by its very nature an ephemeral

art. As a musical score requires performers for its realization,

so a theatrical script requires the energies of many

artists – actors and directors, scenic and costume

designers, carpenters, painters, and tailors – to

create the illusion of a life beyond the reality of the

audience. That illusion ends with the final curtain,

when the dramatis personae remove their masks and take

their bows, revealing themselves as the actors they are.

Going backstage and viewing the sets up close, discovering

the carpentered trusses that support the facades of painted

castles or dungeons, gardens or forests, we may experience

a similar disillusion. But just as we admire the art

of the actor, the professional's ability to become an

other, so too we admire the art of the scenographer,

the craft that must necessarily support the imagination

if we are to believe in that other, staged world.

Joseph Urban was a designer and builder of such alternative

worlds, for the opera stages of Boston and New York and for the Ziegfeld

Follies. Columbia is the fortunate repository of the archives that

document this very active theatrical imagination. The many hundred models,

watercolors, drawings, and plans that constitute the Joseph Urban Collection

permit a more direct access to an era of American stage life than any

photo graphic record might. In these works we encounter the poetic projections

of an architectural imagination, setting the stage for that "heightened

sense of life" that Urban felt was the essential theatrical experience.

As the models and watercolors in this

exhibition demonstrate, Urban's was a world of color. Architect

of Dreams: The Theatrical Vision of Joseph Urban offers

an occasion to reimagine that world and to appreciate

the art of a man who brought a transformative vision

to Broadway.

The exhibition also offers an opportunity

to make available to a largerpublic another important

treasure of the collections of the Columbia University

Libraries. Architect of Dreams was inspired

by the commitment of Jean Ashton, the director of the

Rare Book and Manuscript Library, to restore the glory

of the Urban archival material and was made possible

by the initial research of Gwynedd Cannan, now Curator

of the Performing Arts Collections, who was assisted

by Boni Joi Genser. The full realization of the project

depended upon the enthusiastic engagement of Arnold Aronson,

Professor of Theater Arts, who brought to the project

his own scholarship in theater history – as well

as his graduate student in the School of the Arts, Matthew

Smith, whose catalogue essay addresses Urban's contribution

to American film design.

Like every exhibition in the Miriam

and Ira D. Wallach Gallery, Architect of Dreams and

its accompanying catalogue became reality through the

efforts of Sarah Elliston Weiner, the director of the

gallery, and her staff: Jeanette Silverthorne, assistant

director; Brooke Sperry, administrative assistant; and

the essential Lawrence Soucy, technical coordinator.

The support of the Austrian Cultural

Institute, New York, for this project is gratefully acknowledged.

For her particular interest and assistance, I want to

express a special note of gratitude to Dr. Lee MacCormick

Edwards, the chair of the Wallach Art Gallery Committee

of the Advisory Council of the Department of Art History

and Archaeology. Finally, on behalf of all my colleagues,

I again thank Miriam and Ira D. Wallach, who continue

to share our enthusiasm for the enterprise that they

helped to launch.

David Rosand

Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History

Chairman, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery

vii

PREFACE

COLLECTIONS relating to the development

and history of the theater have been actively gathered

at Columbia since the first decade of the twentieth century.

James Brander Matthews, who had been appointed to the

English faculty at the university in 1891 and was reportedly

the first professor of drama in the United States, encouraged

his students to involve themselves directly in the life

of the stage. A successful playwright himself who would

become a widely published critic, Matthews believed that

the artifacts of theatrical history had a lively role

to play in the education of budding playwrights and producers.

He searched the world tirelessly for masks, puppets,

photographs, posters, programs, and stage models to add

to the dramatic museum that he founded in 1911 to house

his growing collections. To teach Shakespeare, Renaissance

morality plays, and ancient drama, he commissioned the

creation of large plaster replicas of ancient stages;

to introduce his students to the commercial stage of

their own period, he solicited maquettes and working

models from Broadway designers. An inveterate clubman

with a wide acquaintance in the booming New York world

of popular entertainment, he successfully exploited his

social and professional connections to bring an increasingly

diverse array of new materials to the Morningside campus.

After Matthews' death in 1929, the

collections of the Dramatic Museum continued to grow,

thanks to a small endowment, but the materials added

were much more likely to be archival in nature: drawings,

papers, scenic designs, architectural renderings. Mary

Urban's gift of the complete archive of her late husband,

Joseph Urban, came to Columbia in 1958, during this later

period. The Urban papers represented at once a culmination

of Matthews' ambition to capture a sense of the working

theater in its fullest dimension and a rich addition

to the more traditional research collections of the university.

The nearly three hundred set models, bursting out of

their brown paper wrappings, still tied with ribbon marked

with the name of Urban's failed Wiener Werkstatte store

in New York, were supplemented by hundreds of letters,

drawings, photograph albums, and clipping books that

documented the artist's personal history, his life in

America, and his many careers. The collection was a scholar's

dream, promising not only new information about theatrical

design and production but a wealth of unique detail about

turn–of-the-century Viennese art and architecture,

American opera history, popular entertainment, interior

design, and the motion picture business.

Sadly, the Urban collection arrived

at time when the fortunes of the Dramatic Museum were

on the decline and modern conservation techniques were

in their infancy. All that could be done for many decades

was to see that it was safely housed and minimally accessible

to scholars who knew that it was on the campus. When

the museum was formally closed in 1971, the Urban collection

was transferred to the Columbia University Libraries

where it was stored in the stacks, still in the artist's

original containers, just as it had come from the workshop.

Librarians were happy to provide what access they could

to the papers, but the fragile condition of much of the

art work and in particular of the models, which had been

constructed from acidic paper and other ephemeral materials,

limited use. Loans to exhibitions and the publication

of a number of books referring to

ix

the collection were instrumental

in keeping Urban's accomplishments from being forgotten.

Thanks to the Gladys Krieble Delmas

Foundation and to the Preservation and Access Program

of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the story

has a happy end. Funds supplied by these agencies enabled

the Rare Book and Manuscript Library to hire a project

curator for the Joseph Urban archives, charged with the

duty of processing, rehousing, and creating a research

guide for paper collections. The approximately seven

hundred drawings and watercolors in the archives were

matted and boxed. The scrapbooks were microfilmed, and

critical conservation work completed. An online finding

aid, fully searchable, was mounted on the World Wide

Web in 1 999. A consultant was retained to design storage

boxes for the stage models that would allow them to be

accessible for research while still offering adequate

structural support. In the summer of 2000, a pilot project

to rehouse the models was undertaken. Now, in the fall

of the same year, plans are underway to create an image

database of all the visual materials in the Joseph Urban

archives, and initiatives are in progress to raise money

for the physical restoration of the remaining models.

Jean Ashton, Director

Rare Book and Manuscript Library

x

ARCHITECT

OF DREAMS

THE THEATRICAL VISION

OF JOSEPH URBAN

ARNOLD ARONSON

The content of a dream is the

representation of a fulfilled wish .... Adults ...

have also grasped the uselessness of wishing, and after

long practice know how to postpone their desire until

they can find satisfaction by the long and roundabout

path of altering the external world. Sigmund Freud1

The set should be a pure ornamental

fiction which completes the illusion through the analogies

of color and lines with the play .... The spectator

will ... give himself fully to the will of the poet,

and will see, in accordance with his soul, terrible

and charming shapes and dream worlds which nobody but

he will inhabit. And theater will be what it should

be: a pretext for a dream. Pierre Quillard2

ALL STAGE DESIGN and all architecture,

it might be argued, are the realizations of dreams: ideas

that begin as images in the mind and are transformed

by artists and artisans into tangible manifestations

that are made visible to the eye and, in the case of

architecture and interior design, made tactile and corporeal.

Yet these metaphoric dreams, when realized, do not necessarily

possess the qualities we mean when we describe something

as "dreamlike." Buildings and rooms have practical

functions that root us in the here and now; stage designs

often work best when they do not call attention to themselves

or when they serve as simulacra for the recognizable,

quotidian world. But Joseph Urban – architect,

scenographer, illustrator, designer – rarely limited

himself to mere functionality. His works – whether

department stores, hotels, castles, bridges, restaurants,

theaters, art pavilions, book illustrations, or the lavish

and often haunting settings for operas, musicals, pageants,

and the Ziegfeld Follies – almost always

seemed to be the consummation of fantastical visions

and flights of fancy intended to take the spectator or

occupant on a journey through the imaginary recesses

of the soul.

As the title of this exhibition and

its catalogue suggests, Urban straddled two worlds: architecture

and theater. On the one hand, there was an innate theatricality

to Urban's architecture – theatrical in the sense

of being dramatic and playful, and theatrically conceived

as virtual stage settings in which real people are characters

moving through carefully designed spaces. A critic for

the New Yorker in 1928, seeking what he thought

to be an appropriately derisive term to describe Hearst's

International Magazine Building (fig. 1), condemned it

as "theatric architecture."3 On the

other hand, there is an architectural quality to Urban's

stage designs. Although he rarely created the sculptural

environments of his scenographic contemporaries such

as Adolph Appia, Edward Gordon Craig, or Robert Edmond

Jones – Urban relied much more on painted and decorative

elements – an underlying use of structural detail

and a sense of fully

1

constructed spaces pervaded his designs.

No matter how fanciful or fantastic the imagery he devised,

whether onstage or in a book illustration, there was

a palpable reality to the representation – as if

one could physically enter into this imaginary world.

But always, the worlds of architecture and theater intertwined:

Joseph Urban built dreamscapes.

Carl Maria Georg Joseph Urban, born

in Vienna on 26 May 1872, was one of the most significant

stage designers of the early twentieth century. The statistics

alone are impressive: from 1904 to 1914 more than fifty

productions for theaters and opera houses in Vienna and

throughout Europe; thirty productions for the short–lived

but influential Boston Opera Company, as designer and

stage director from 1912 to 1914; fifty–one productions

for the Metropolitan Opera of New York between 1917 and

his death on 10 July 1933 (some of which remained in

the repertory until the mid–1960s); all of Florenz

Ziegfeld's productions (Follies, Midnight

Frolics, and eighteen musicals) from 1915 on; twenty–six

musicals and sixteen plays for other Broadway producers;

plus numerous films, mostly for William Randolph Hearst's

production company. All this, of course, was in addition

to his continued work as an architect, interior designer,

and illustrator which had begun in the early 1890s. Urban's

importance lay in his virtually unprecedented use of

color, his introduction to American theater of many of

the techniques and principles of the New Stagecraft,

and his architectural sensibility at a time when most

stage designers came from a background or training in

visual art.

Despite his acknowledged importance

and influence, he has remained surprisingly underrated,

even forgotten. I will discuss possible reasons below,

but perhaps it comes down to a few simple facts: He wrote

no theoretical essays, nor did he set down his philosophy

in a book; he was a practical man of the theater and

while his ultimately more famous colleagues published

portfolios of unrealized visionary designs, he turned

out actual settings which inevitably had to fit the very

real demands of production (even his unbuilt theaters

were designed for actual projects that never came to

fruition); and finally, his innovations were often in

the service of popular entertainment and spectacle (or

in the case of architecture, in the lavish homes of the

rich and famous). Aesthetically, he was never willing – never

saw a reason – to fully abandon ornament or the

decorative, so his architecture was out of sync with

the developing International Style, and his stage work

was never as abstract as that of the most esteemed designers

of the New Stagecraft. But as the composer Deems Taylor

noted in a posthumous appreciation of Urban:

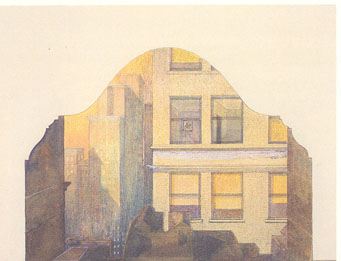

Fig. 1 International Magazine Building, New York, 1929

(cat. 17a)

2

His greatest misfortune, as well

as his greatest glory, is the fact that his contributions

to his art were so fundamental that they are taken

for granted... He revolutionized the scene designer's

position in the American theatrical world. He was the

first to make clear that the designing of stage sets

is an art, and that the man who designs them is an

artist – or should be.4

SYMBOLISM AND DREAMS

Urban came of age in the Vienna of

the 1890s, the Vienna of vibrant theater and opera, a

brilliant explosion of fine and decorative arts, and,

of course, of Sigmund Freud. It was a city where pleasure

and intellect intersected, and where the exploration

of the function of art and the structure of the mind

were approached with equal passion. Like the Viennese

Secessionist artists who influenced him, Urban had some

affinities with the symbolist poets and painters, although

his work did not derive from quite the same spiritual

and aesthetic sources, nor did it necessarily have the

same ends. But clearly, some aspect of symbolism struck

a chord within him, perhaps (appropriately enough) subconsciously.

The artist Hermann Barr may have been speaking for most

of the young Viennese artists of the day when he proclaimed

in 1894, "Art now wants to get away from naturalism

and look for something new. What that may be, no one

knows; the urge is confused and unsatisfied. .. . Only

to get away, to get away at all costs from the clear

light of reality into the dark, the unknown and the hidden."5 The

dark, unknown, and hidden was precisely the realm of

symbolism, whose driving force was the desire to explore

the human psyche and uncover inner truths hidden beneath

surface realities. The symbolist movement that emerged

in Paris in the 1880s under the leadership of the poet

Stephane Mallarme was heavily influenced by the writings

of the composer Richard Wagner, particularly by the latter's

quest for a mythological foundation for the creation

of art which would then serve to unify society through

a communal response to the art work. The symbolists also

drew upon the mystical and sublime elements of the poetry

of Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Baudelaire. All nineteenth–century

art, literature, and theater, in fact, seemed to have

been moving ineluctably from the replication of observable

phenomena to the revelation of dream worlds and subconscious

landscapes. When Pierre Quillard, a now little–known

symbolist playwright and poet, described a theater as "a

pretext for a dream" (see epigraph), he could easily

have been characterizing the creations of Joseph Urban.

The symbolist painters sought to move from an art of

objective images, or even the suggestive work of the

impressionists, to an art of subjective reality that

would affect the senses directly, without the mediation

of rational thought.

Whether or not Urban was directly

influenced by the symbolists, he was certainly absorbing

the symbolist–inflected Jugendstil art all around

him. Moreover, he could not have been unaware of Freud's

efforts to expose the workings of the mind through the

agency of dreams. The world that Urban created on the

stage – of vivid color, architectural detail, and

visual fantasy – reflected these intertwined realms

of art and psychology.

While the creation of dreamscapes

may seem an appropriate aim of theater design, it perhaps

seems less understandable with architecture. Yet architecture,

too, is a surprisingly apt medium for dreams. In The

Poetics of Space, his study of the human response

to space and its relation to the subconscious, the modern

French philosopher Gaston Bachelard described the house

as both a locus and generator of dreams:

The house protects the

dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace. ...The

places in which we have experienced daydreaming reconstitute

themselves in a new daydream, and it is because our memories

of former dwelling–places are relived as daydreams

that these dwelling–places of the past remain in

us for all time....the house is one of the greatest powers

of integration for the thoughts, memories and dreams

of mankind.6

Urban began his career as an architect,

and many of his early projects

3

were, in fact, dwellings – but

not ordinary or bourgeois homes. His very first commission,

received at the amazingly young age of nineteen, before

he had even finished his studies, was to create a new

wing for the Abdin Palace in Cairo for the young Khedive

of Egypt. Later in the decade he would create the Esterhazy

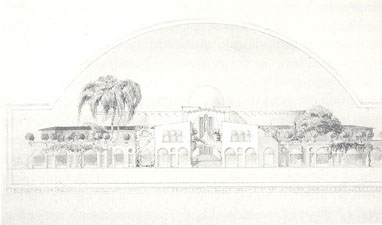

Castle in St. Abraham, Hungary (fig. 2) – a pleasure

palace with its white marble facade decorated with gold

medallions and floral patterns and its individual rooms

that were riots of color, pattern, and geometric shapes.

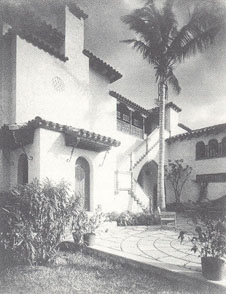

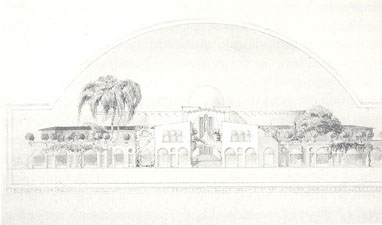

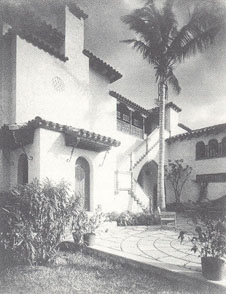

In the 1920s, in such creations as Mar–a-Lago in

Palm Beach, Florida (fig. 3), he was a major influence,

along with many of his fellow Austrian architects, in

developing the Spanish colonial revival style – with

its fantastical and eclectic mix of Spanish, Venetian,

and Portuguese architectural elements – which came

to define the extravagant homes, clubs, and resorts of

the Florida land boom. But even his more conservative

homes were carefully crafted visions that integrated

the practical needs of domestic architecture with the

fantasies, memories, and dreams of those who would dwell

within.

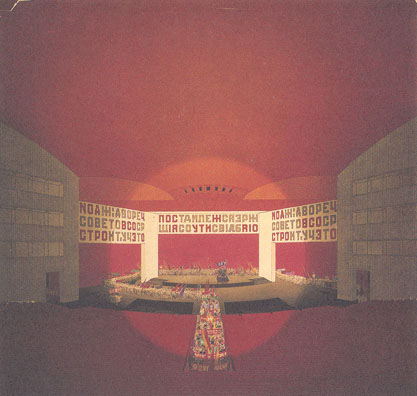

GESAMTKUNSTWERK

The notion of gesamtkunstwerk – the

total or unified art work – was the guiding principle

of Richard Wagner's approach to artistic creation. Simply

put (something Wagner rarely did in his major theoretical

writings of the mid–nineteenth century), all the

elements of operatic production –music, orchestration,

stage design, costume, acting, singing, and even the

architectural environment that shaped the audience experience – were

to be unified under the vision of a single artist so

as to create a single experience for the massed spectators.

The impetus for Wagner's approach came not only from

the belief that theater and opera were equivalent (perhaps

even superior) to the other arts, but from the mundane

aspects of contemporary production practice and the inherent

pitfalls of the collaborative process, all of which often

contrived to turn the typical dramatic spectacle of the

mid–nineteenth century into a nearly incoherent

pastiche. Writers customarily sold their plays to theaters

which could produce them with no authorial input; composers

had limited control over the performance of their music;

actors chose their own costumes according to their personal

tastes, budgets, and only rarely for appropriateness

to the role; settings were, more often than not, composed

of stock scenic units that indicated a generic castle,

interior, forest, or the like as needed; rehearsals were

minimal and performances, therefore, lacked cohesion;

and the relation between the images onstage and the environment

of the auditorium was never considered. If, as Wagner

believed, the art work reflected a spiritual as well

as aesthetic quest, then it was crucial that all elements

of production be focused on the realization of the artist's

vision.

While Urban never used the term gesamtkunstwerk (at

least not in any interviews or in the few articles he

wrote), he was clearly a proponent of the unified art

work of the stage. That approach was largely unknown

in the United States in 1912 when Urban did his first

work for the Boston Opera, and it clearly struck the

very perceptive critic of the Boston Evening Transcript,

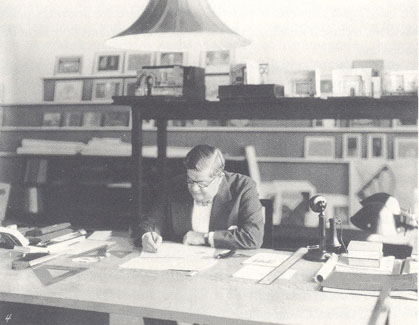

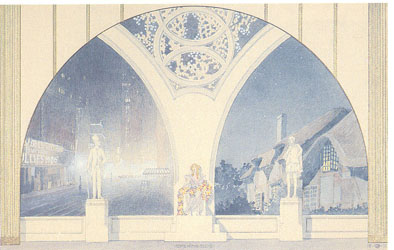

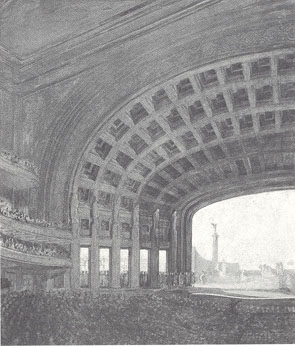

H.T. Parker, in his review of The Tales of Hoffmann (fig.

4): "Music, drama, and setting were wholly fused

into the compassing of perfect atmosphere and illusion."7 In

an interview in 1913 Urban described inszenierung – the

German word for the total effect of the theatrical event,

equivalent to the more prevalent French term mise en

scene – in terms that reflect the influence of the

Wagnerian gesamtkunstwerk:

The new art of the theater is more

than a matter of scenery; it concerns the entire production.

The scenery is vain unless it fits the play or the

playing or unless they fit it. The new art is a fusion

of the pictorial with the dramatic. It demands not

only new designers of scenery, but new stage managers

who understand how to train actors in speech, gesture

and movement, harmonizing with the scenery.8

4

Fig. 2 Esterhazy Castle, St. Abraham, Hungary, exterior,

1899, watercolor.

Collection Gerhard Trumler

Fig. 3 Mar–a-Lago,

Palm Beach, 1926, photograph, 8 x 10 in.

Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

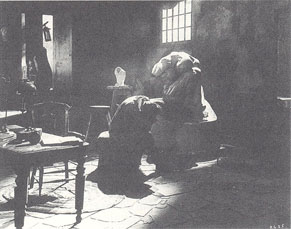

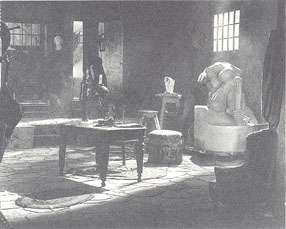

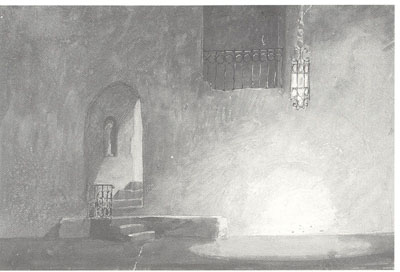

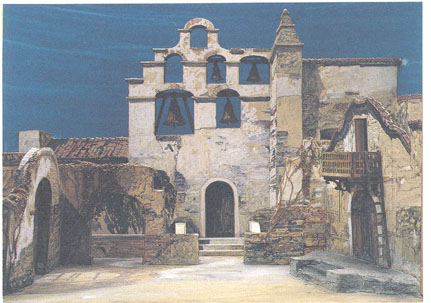

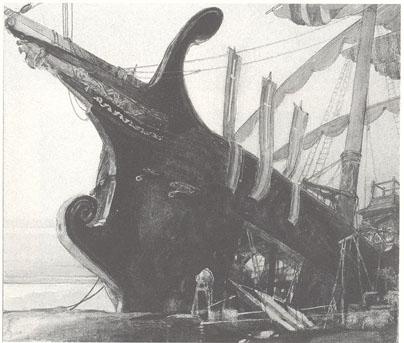

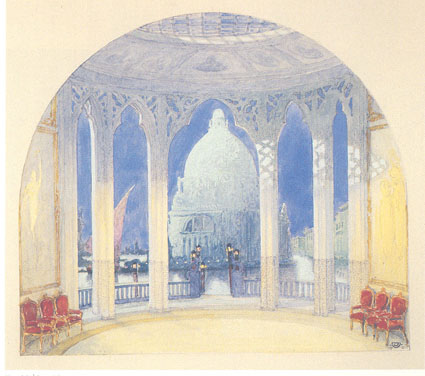

Fig. 4 Contes

d'Hoffmann, 1912 (cat. 29b)

While theater scholars and historians

associate the idea of gesamtkunstwerk solely

with Wagner and his theatrical heirs, the concept actually

spread to other artistic disciplines as well. Inspired

by that monumental Romantic work of urban planning, the

Ringstrasse – the circular boulevard around central

Vienna which was created as a unified work of civic architecture,

private dwellings, and public and official space – the

Viennese artists at the start of the twentieth century

(particularly those of the Wiener Werkstatte) believed

in "the integration of all the various design elements

in a single aesthetic environment," as the art historian

Jane Kallir stated.9 Large–scale public

works were no longer an option by the end of the century,10 so

young artists turned their energies to private homes

which were designed as theatrical environments: the architectural

space

5

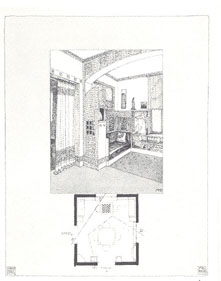

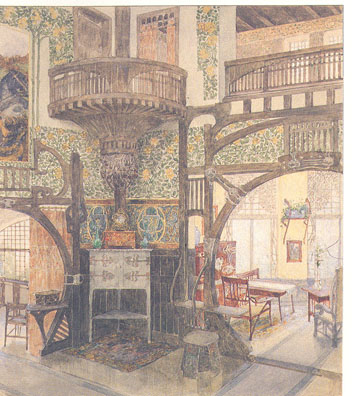

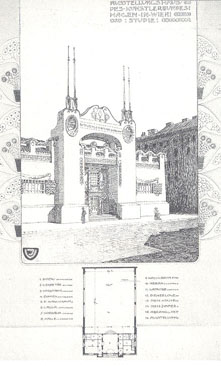

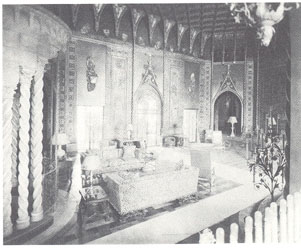

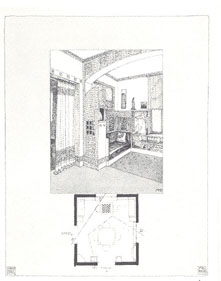

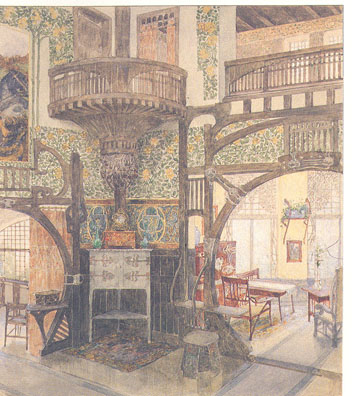

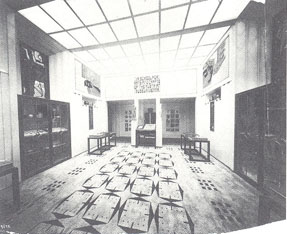

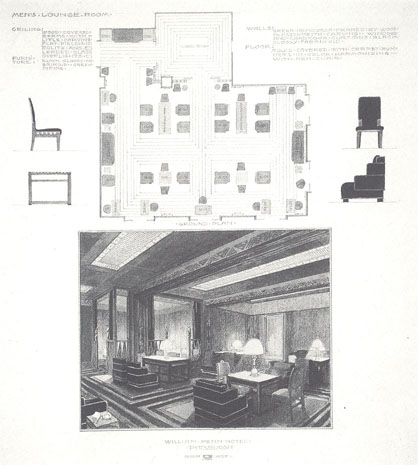

Fig. 5 Goltz Villa, Vienna, plan and view of interior,

1902 (cat. 5a)

became a comprehensive milieu in which

every element down to the smallest detail was designed,

just as it would be in a theatrical setting. And just

as the theater employed an ensemble of artisans from

carpenters to electricians, so the architects employed

an ensemble of craftsmen including painters, paperhangers,

and plumbers, all working toward the realization of a

single artistic vision.11 Urban, too, was

a proponent of the unified approach. "If a building

is to reflect the efforts of artistic planning," he

declared, "it must be harmonious up to the minutest

detail."12 One of the practices that frustrated

Urban as he developed his architectural career in the

United States was the custom of using jobbed–in

contractors so that there was no unity of style nor singularity

of purpose among the crafts workers. More important for

Urban, however, was the need for the architecture to

reflect the society and environment in which it existed.

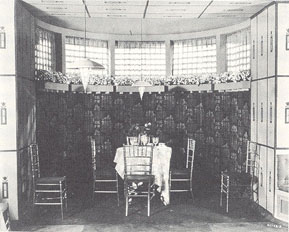

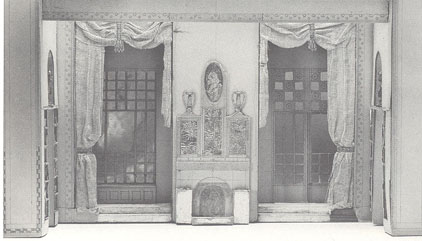

Fig. 6 Goltz Villa, game and music rooms, 1902 (cat.

5b)

Architecture should be adapted to

the climate, temperament, needs and the national characteristics

of a people. A good architect should know his country

from one end to the other, know its people and understand

their ideals. Only then can he hope to build intelligently.

Architecture should be as much a part of the time and

of the place as the current news. It is about time

that we outgrew ancient cultural styles and intermediate

mushroom growths. To have a Colonial or a Renaissance

house nestled in the heart of New York is as absurd

as doing modern day jobs with Colonial or Renaissance

tools.13

The analogy between theater and architecture,

however, breaks down on at least one detail. In the theater,

the actors are part of the design, as it were; their

costumes and their movements are specifically integrated

into the setting. But architects have no control over

the look or specific movements of those who use their

buildings. There is an undoubtedly apocryphal

6

anecdote about the designer Eduard

Wimmer–Wisgrill who, on a visit to the Stoclet mansion

in Brussels, which had been designed by Josef Hoffmann,

was horrified at the way in which Madame Stoclet's Paris

fashions clashed with the Werkstatte decor. Upon his

return to Vienna he established a fashion workshop for

the Werkstatte, presumably so that the home owners could

be suitably costumed for their settings.14 Even

if this were the true genesis of the costume workshop,

clearly there is no way to control the total architectural

environment once it is out of the architect's hands.

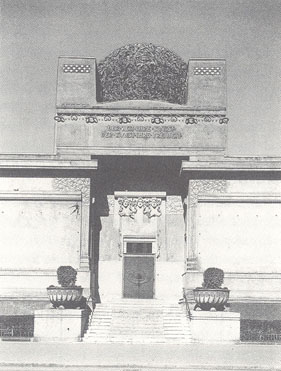

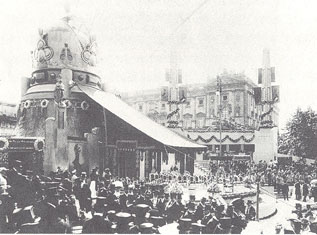

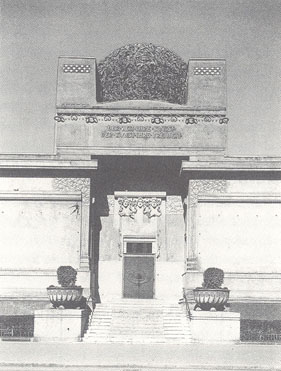

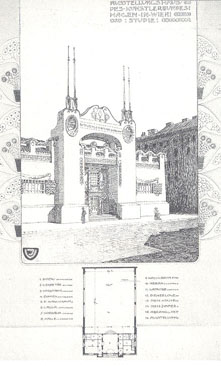

In all of Urban's architectural projects,

the interiors were completely coordinated: tables, chairs,

curtains, floor tiles, wallpaper and painted decor, lighting

fixtures, utensils, and appliances were all designed

for the space. Urban won numerous awards for his totally

designed exhibition spaces, such as those for the Kunstlerhaus

exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1900 and the Austrian

pavilion at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint

Louis in 1904 (fig. 52). The space for presenting art

was in itself a work of art: a fully integrated environment.

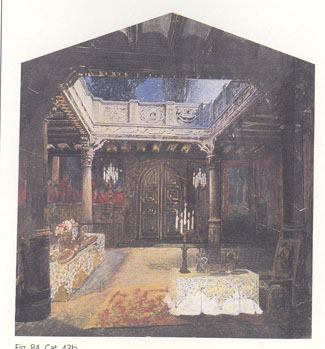

That Urban saw his architectural creations as theatrical

spaces, at least subconsciously, may be deduced by looking

at the plan and two views of a room for the Goltz Villa

(figs. 5–6). Each of the two depictions is presented

as if it were a traditional box set (a stage setting

of a room viewed as if one wall were removed) with the

corner of the room forming an off–center apex.

What is particularly revealing is that the perspective

seems to be skewed if one compares the view to the plan.

The viewer, however, is not standing on the section line

as the plan indicates but rather is looking at the room

as if it were a stage setting viewed from the auditorium.

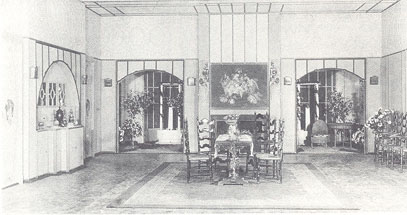

The rendering and plan of the Goltz room compares interestingly

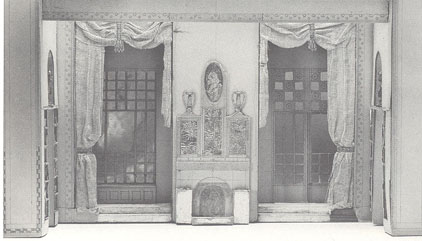

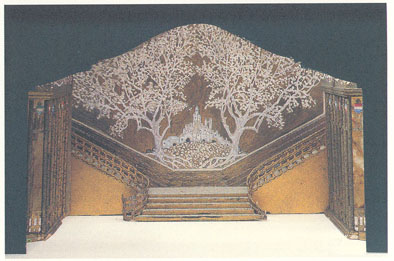

with Urban's stage sets, such as that for Apple Blossoms (fig.

7), a 1919 musical in which Fred and Adele Astaire made

their debuts. The room depicted onstage is more elegant

and the walls certainly taller than those in the Goltz

Villa, but the ground plan – and the relation of

the implied audience to the space – is remarkably

similar.

Of course, much of Urban's work could

be described as "theatrical." The prominent place

of the performing arts in Viennese society and the general

aim of many of the Secessionist artists to unify all

aspects of art and society inevitably led to a theatricalization

of the arts. But in Urban's work, the theater became

an implicit metaphor. His design for the Kaiser Bridge,

for example – a structure created to join the Kunstlerhaus

and the Musikverein for the celebration of Franz Josef's

fiftieth anniversary as

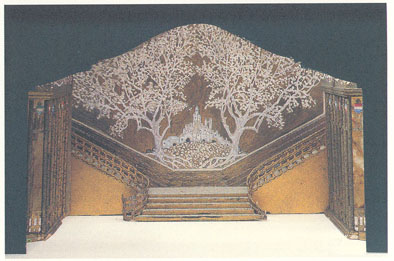

Fig. 7 Apple

Blossoms, 1919 (cat. 56)

7

emperor – creates what amounts to a proscenium arch

through which the baroque Karlskirche could be seen (fig.

8). And while the decor of the bridge consisted of a strong

interplay of linear and geometric forms layered with Art

Nouveau filigree, the wooden structure recalled the triumphal

arches and festival stages of medieval royal entries and

Renaissance pageants. It was a decidedly theatrical space.

The arch–as-proscenium recurs as a separator between

rooms in the Esterhazy Castle (fig. 9) – it appears

to be structural but is really a decorative element that

frames the

Fig. 8 Kaiser Bridge, Vienna, 1898, watercolor, 11 1/2

x 8 1/2 in.

Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

space behind it in a manner almost

identical to the archway of the Kaiser Bridge. The proscenium

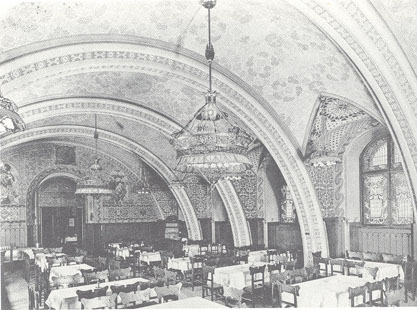

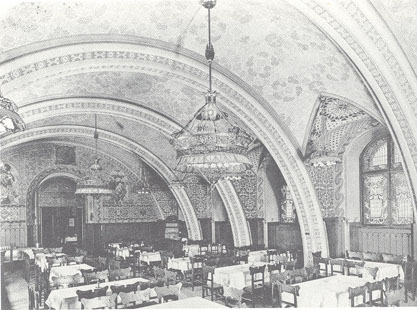

motif was picked up in the Rathauskeller, the restaurant

in the basement of the Vienna town hall. The structural

arches that created the ceiling inevitably evoked the

comparison, but Urban emphatically accentuated the theatrical

parallel in his decorative scheme. One went down a flight

of stairs through an arch as if entering into a theatrical

world. Once in the restaurant, the repeated

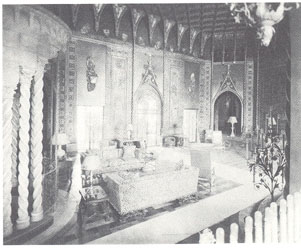

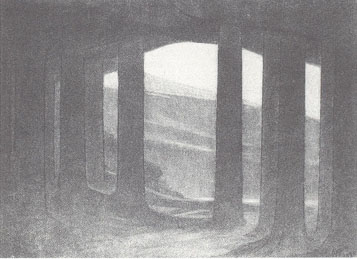

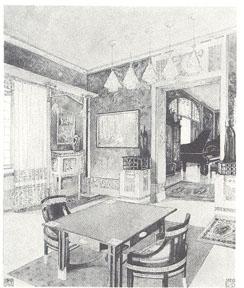

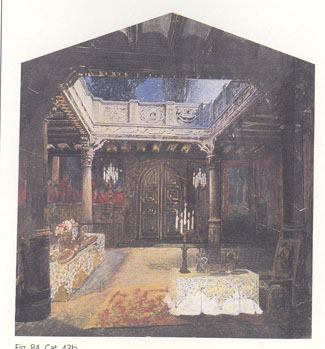

Fig. 9 Esterhazy Castle, interior, 1899 (cat. 3)

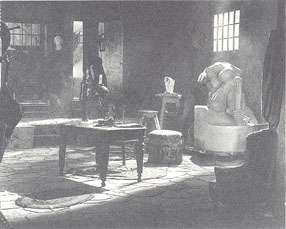

8

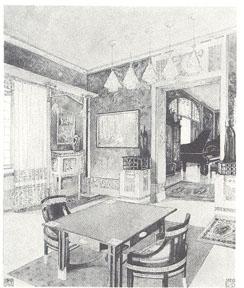

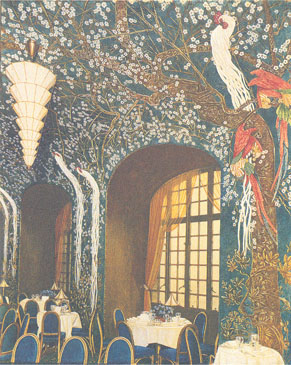

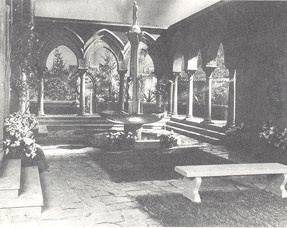

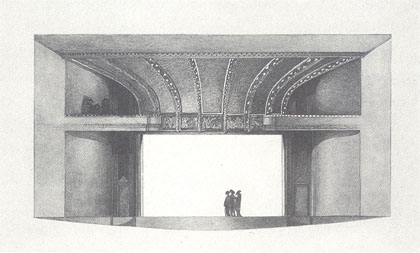

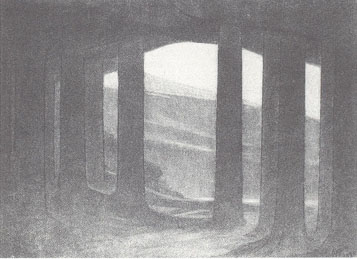

Fig. 10 Rathauskeller, Vienna, large dining room, 1899

(cat. 4c)

arches of the ceiling created an

illusion of infinite vistas (fig. 10). (Again, while

the repeated Arches were a necessary by–product

of the architecture, they could not help but recall the

repeating proscenium motif of Wagner's Festspielhaus

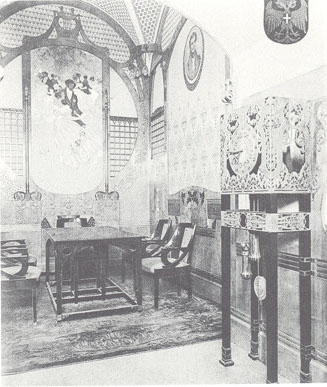

at Bayreuth.) The smaller private rooms off the main

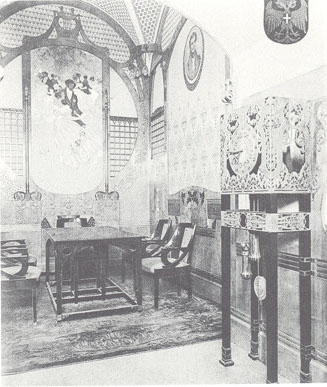

dining hall of the Rathauskeller were works of total

design, with every surface and every piece of furniture

part of the architectural scenography (fig. 11).

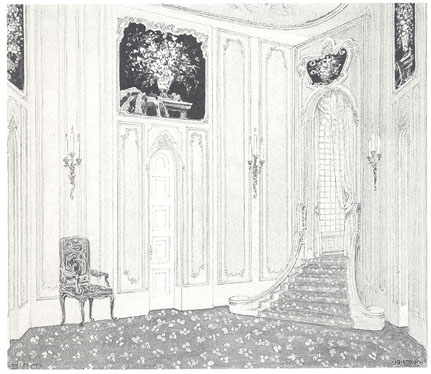

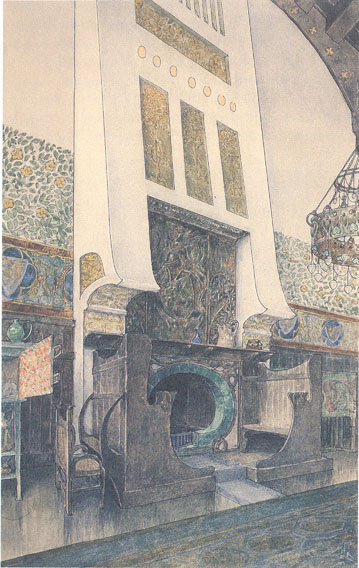

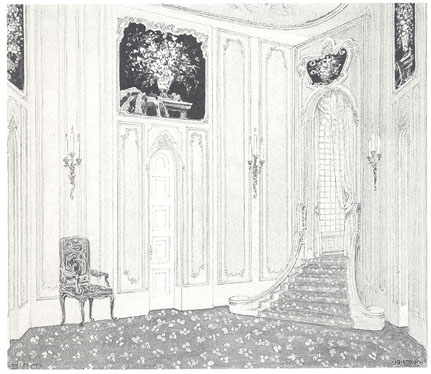

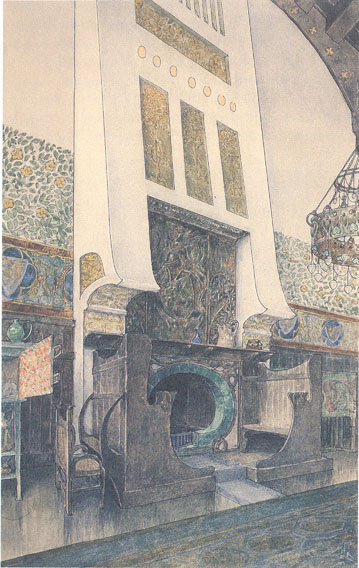

The proscenium motif even emerges

in the fireplace of the Esterhazy Castle (fig. 12). The

fireplace opening was a curved blue oval, itself framed

by a rectangular mantle topped by a massive, vaguely

Egyptian chimney breast within which was yet another

rectangular Art Nouveau relief. Two high–backed

benches at right angles to the fireplace provided further

framing as well as "audience" seating, funneling

all attention toward the "proscenium." The arrangement

of the benches was repeated in

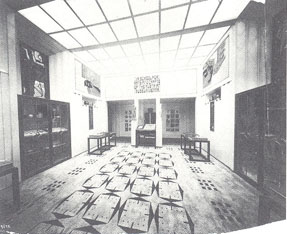

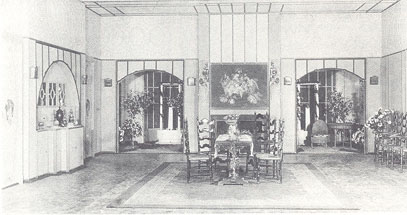

Fig. 11 Rathauskeller, Strauss–Lanner Room (cat.

4a)

9

Fig. 12 Esterhazy Castle, fireplace, 1899, watercolor,93/4

x 63/8 in.

Rare Book And Manuscript Library, Columbia University

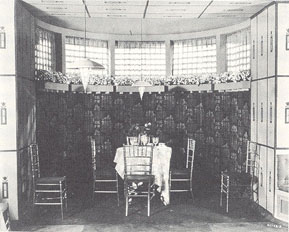

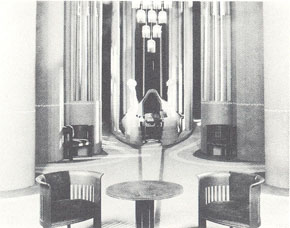

several Urban interiors, notably in

the entrance foyer to the Wiener Werkstatte shop that

Urban opened on Fifth Avenue to sell the works of his

Austrian colleagues in order to raise money for them

following World War I (fig. 13). (The shop, unfortunately,

was a financial failure.) Here the benches have been

replaced by Urban's modernist take on Queen Anne chairs.

Fig. 13 Wiener

Werkstatte shop, New York, 1922, photograph, 10x8

in.

Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

10

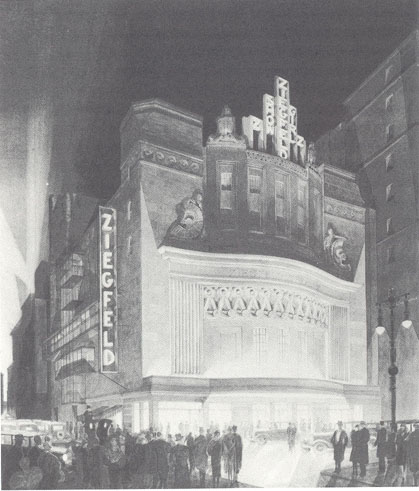

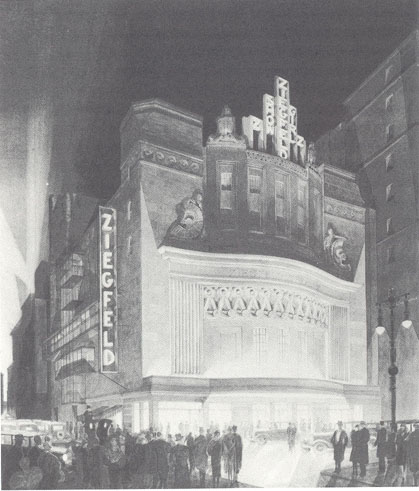

Fig. 14 Ziegfeld

Theatre, New York, facade, 1926–27 (cat. 9a)

THEATRICAL ARCHITECTURE

The term "theatrical" – a

dismissive and pejorative term when used by Urban's architectural

critics – referred to the fact that his designs

tended toward the flamboyant, decorative, and illusionistic.

In an era when, increasingly, the credo was "form

follows function," Urban's architecture often masked

its structures; form followed fantasy. Urban believed

that public space should be designed with the same sense

of total environment and aesthetic pleasure with which

one created a stage setting. He was creating dramatic

worlds for real people. Following the metaphor to its

logical end, his architectural projects could all be

seen as "theaters," an impression reinforced

by his frank assertion that a building facade was a form

of advertising – a marquee.15 Just as

Renaissance palaces advertised the power and culture

of the Medicis, he explained, so too "a beautiful

building is the sandwich board of its owner."16 This

philosophy was his rationale for the billowing facade

of the Ziegfeld Theatre, which opened on Sixth Avenue

and 54th Street in 1927 (fig. 14).

The whole idea back of

the Ziegfeld Theatre was the creation of an architectural

design which should express in every detail the fact

that here was a modern playhouse for modern musical shows.

. . .The strong decorative elements of this part of the

facade have nothing to do with usual architectonic proportions.

They are meant as a poster for the theater.17

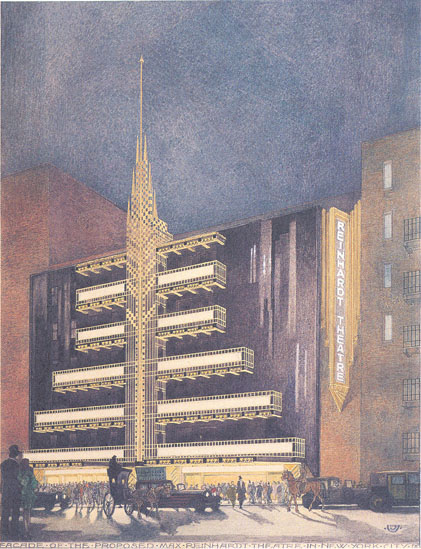

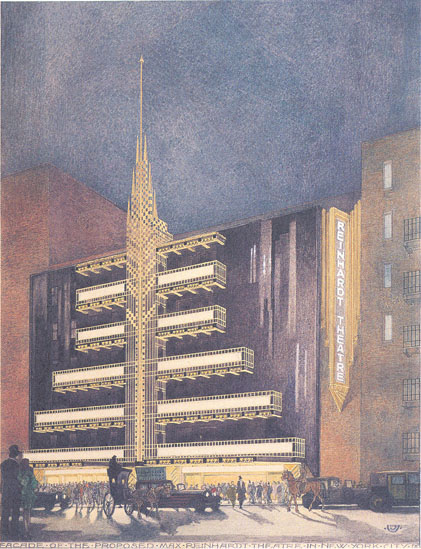

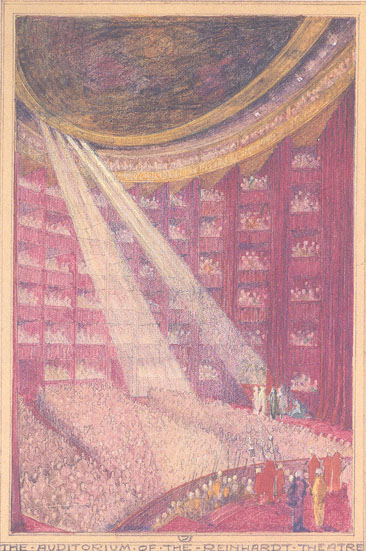

For theater buildings in New York,

wedged into narrow spots on crowded streets, Urban felt

there was a particular challenge that could be met through

designing the public face of the building "around

the electric light sign and incidentally the fire–escape

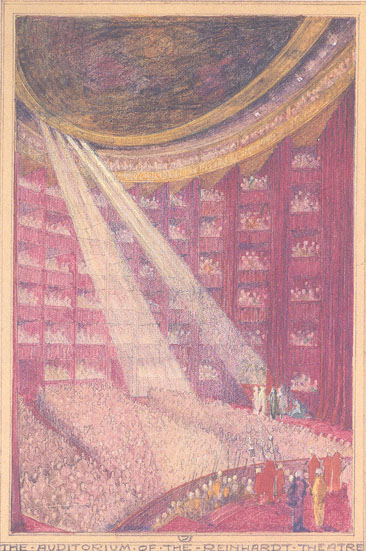

and the marquee." The proposed Max Reinhardt Theatre

(fig. 15), intended for the productions of the innovative

German director but unfortunately never built, was perhaps

the epitome of this philosophy. The facade was to be

covered in a skin of Vitrolite, "a gleaming black

glass." Cutting horizontally across

11

Fig. 15 Reinhardt

Theatre (proposed), New York, facade, 1928 (cat.

14a)

this surface was to be a pyramid of

six fire escapes outlined in gold metal–work with

white panels that would contain advertising signs, while

the center of the façade would be bisected by a

tower of gold grillwork containing the emergency stairs

and which was topped with a delicate, perforated late–gothic

spire. The result, at least on paper, was a facade of

dramatic contrasts which radiated like a gleaming beacon

into the New York City night. "A decorative scheme

of such force," he explained, becomes a necessity

when the theater has to compete with the sheer bulk and

height of surrounding skyscrapers. It is far too easy

for a low fa9ade to be crushed and lost in the confusion

of metropolitan building."18

The facade of the Bedell company store

on 34th Street (fig. 16) of 1928 used the same gleaming

black surface material. In place of the horizontal fire

escapes – unnecessary for a department store – there

was a massive

Fig. 16 Bedell

Store, New York, facade, 1928 (cat. 12a)

12

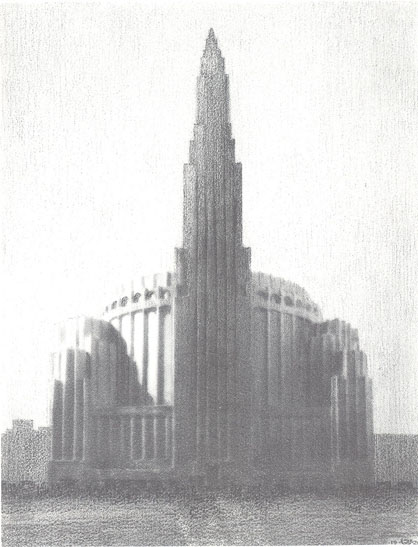

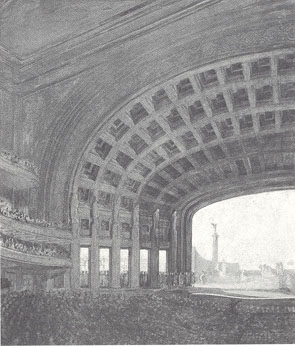

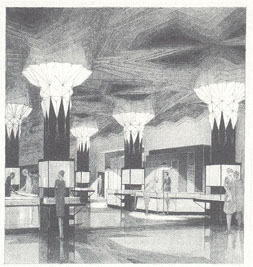

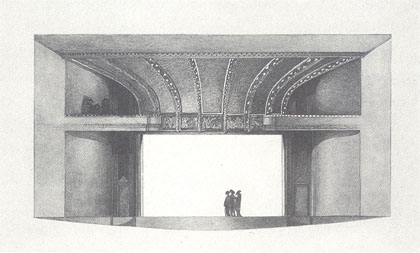

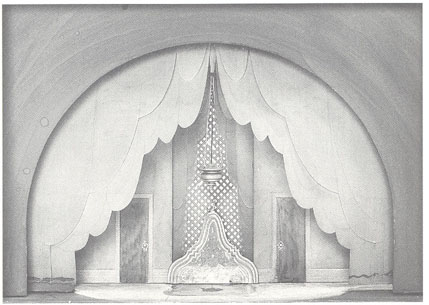

Fig. 17 Metropolitan

Opera House (proposed), New York, facade, 1926–27 (cat.

8a)

Fig. 18 Metropolitan

Opera House, proscenium, 1926–27 (cat. 8d)

curved grillwork over the entrance

which served, in essence, as a stunning scenographic

device, similar to the crowns that sat above the royal

boxes in baroque theaters. Furthermore, the plate glass

shop windows along the street and the show windows along

an interior arcade functioned not unlike theatrical prosceniums.

Significantly, the architect Shepard Vogelge–sang,

who wrote about the design, compared the lighted columns

of the arcade to Hans Poelzig's design for the Grosses

Schauspielhaus, Reinhardt's monumental theater in Berlin.19

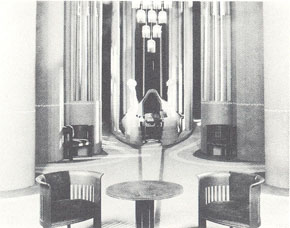

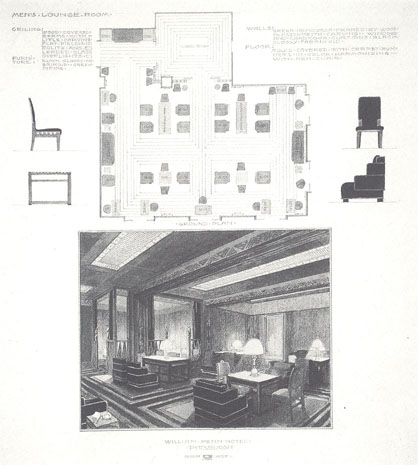

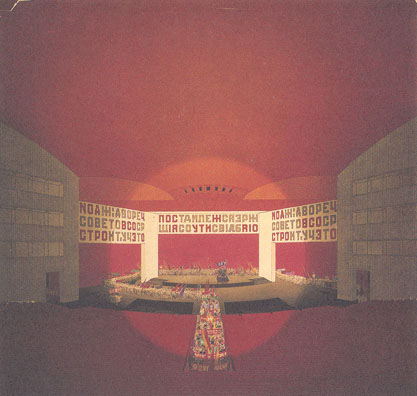

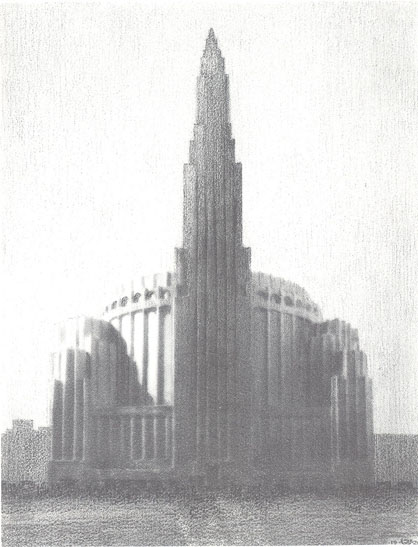

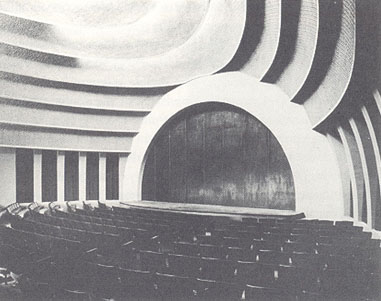

For sheer theatricality, however,

nothing in Urban's work surpasses his schemes for a new

Metropolitan Opera House (figs. 17–18). It is the

13

embodiment of his belief that "a

theater is more than a stage and auditorium. It is a

place in which to experience a heightened sense of life."20 Otto

Kahn, the chairman of the Metropolitan's board of directors,

began planning for a new opera house in the mid–1920s.

Of the several sites under consideration, one on West

57th Street between Eighth and Ninth avenues seemed the

most feasible. Urban sought an architecture that would

be as radical as Wagner's theater at Bayreuth and yet

one in which the social functions and spaces – foyers,

smoking rooms, rest rooms, dining areas – were

to be carefully considered. "The purpose back of

the building of a new opera house today," declared

Urban, "must be to find an architectural form so

free that it can in turn set free every modern impulse

which would tend to heighten and develop the form of

grand opera, to make it not grandiose but grand, majestic,

as large in spirit as in scale."21 Urban's

several proposals do, in fact, possess breathtaking grandeur,

theatricality, and splendor. The exterior was almost

fortress like, the interior suggested a cathedral. But

his plans may also be seen as excessive, even vulgar – at

least one critic likened it to Albert Speer's creations

for Hitler. Ultimately, it was a theatrical vision for

a theatrical space. Yet, because of disagreements among

board members, rivalries among architects, disputes over

accommodations for patrons (Urban's plan to extend the

stage the entire width of the theater would have eliminated

the side boxes), and ultimately financial difficulties

and the Depression, the project was never realized; the

Metropolitan Opera had to wait until the mid–1960s

and Lincoln Center for a new building. It is unlikely,

however, that funds could ever have been raised for such

a structure; nor is it clear that the opera company could

have survived the debt and operating costs had it been

built. But the future of New York culture, not to mention

Manhattan's West Side, would have been permanently changed

and it is intriguing to speculate whether Lincoln Center

would then have been built.

URBAN AND THE NEW STAGECRAFT

In 1911 Urban was commissioned to

design three productions for the new Boston Opera Company's

spring 1912 season: Pelleas et Melisande, Hansel

und Gretel, and Tristan und Isolde. These

productions marked a turning point in American scenographic

history. Urban was subsequently appointed stage director

and designer for the company, and he moved to Boston

later in 1912. Scene painting in America at that time

was generally a poor version of easel painting. Pictures

were painted on canvas and most often were illuminated

under undifferentiated white light which flattened the

image, destroyed any sense of illusion, and emphasized

the wrinkles and flaws in the canvas. In the words of

the producer and critic Kenneth Macgowan, this scenery

was typified by "large–sized colored cut–outs

such as ornament Christmas extravaganzas .. .[and] landscapes

and elaborately paneled rooms after the manner of bad

mid–century oil-paintings in spasmodic three dimensions."22 Even

the most artistically painted versions of such scenery – and

there were some notable scenic studios at the time – were

nonetheless a kind of semiotic code; they suggested or

pointed to the particular, often generic, environment

in which the audience was to imagine the play or opera

unfolding but which never could be mistaken for the real

thing. Urban's Pelleas, however, was a startling

revelation to Boston audiences. As described by Macgowan, "it

was made of strange, shadowed, and sun–flecked glimpses

of wood and fountain, tower, grotto, and castle, vivid

in varied color, full of the soft unworldliness of Debussy's

music."23 Summing up Urban's Boston work,

Macgowan declared that "his scenery, costumes, and

lights have given the productions of the opera–house

a distinction which they could never have obtained through

their singing and acting alone."24 This

is a remarkable statement. For perhaps the first time

anywhere, certainly for the first time in this country,

a critic was acknowledging the role of the mise en scène

or inszenierung in

14

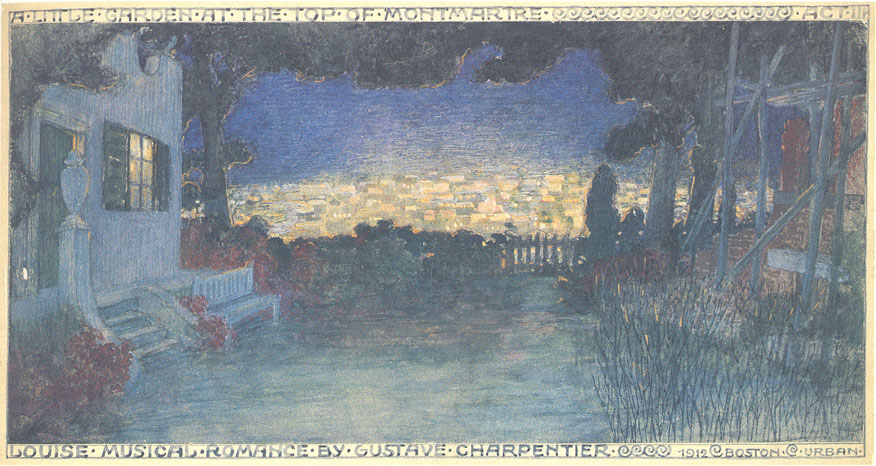

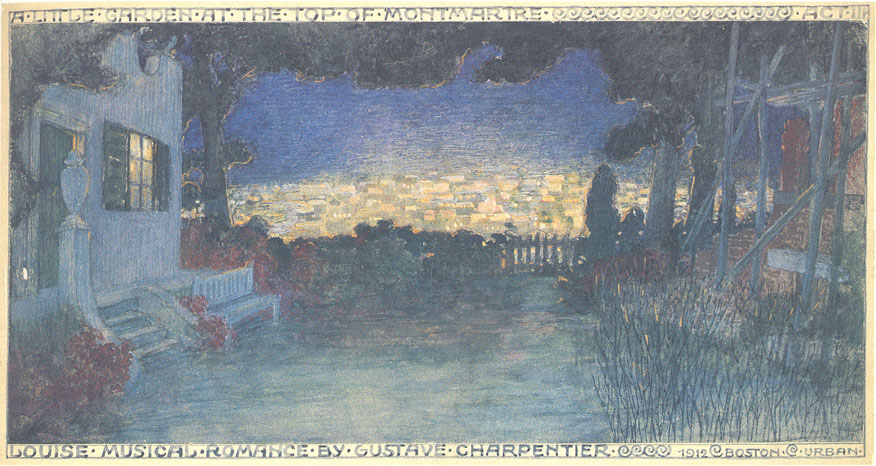

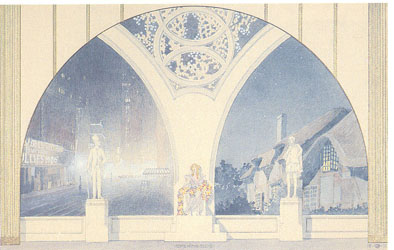

Fig. 19 Louise,

1912 (cat. 30)

15

the theatrical event, placing it on

the same artistic level as the music and singing and

affirming its ability to shape audience response.

The new approach to scenography, known

as the New Stagecraft, was a response to the increasingly

crowded and overly detailed excesses of late nineteenth–century

stage naturalism. In place of simulation, representation,

and illusion, the New Stagecraft was typified by simplicity,

suggestion, and impressionism. Unnecessary details and

clutter were stripped away; locale was created through

the spare use of a few emblematic elements; and the scene

was made to suggest "an atmosphere of reality, not

reality itself; the impression of things, not crude,

literal representations."25 In 1915 for

an article in Theatre Magazine, Urban was asked

to define "modern" design. "Certain painters,

weary of complex combinations

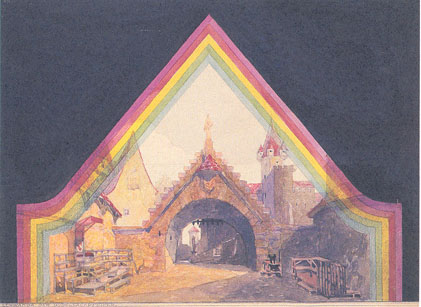

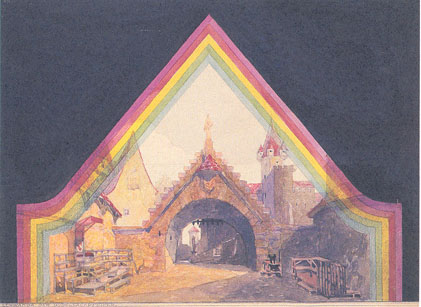

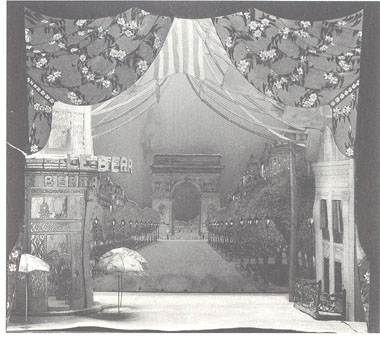

Fig. 20 Schwanda,

der Dudelsakpfeifer, entrance to city, 1931 (cat.

45)

[Show larger image]

of form and color, have sought to

return to simple lines and a palette of primary colors," he

replied. "Call it modern, if you must, it is in reality

Middle Age and Orient mixed. It is Albrecht Durer, Memling,

Watteau, Chardin . . . . A formula for modern art? It

is this – I think - grace and simplicity."26

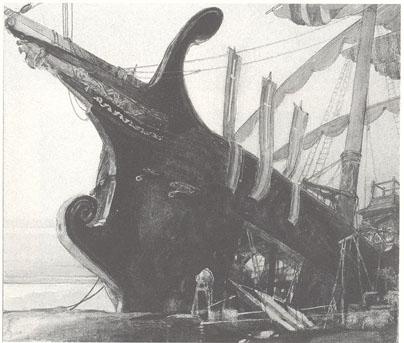

This grace and simplicity could be

seen in several of his Boston productions. For Wagner's Tristan

und Isolde, for instance, the usually detailed depiction

of a ship was eliminated. In its place was Isolde's couch

on a bare stage enclosed by towering, dimly lighted,

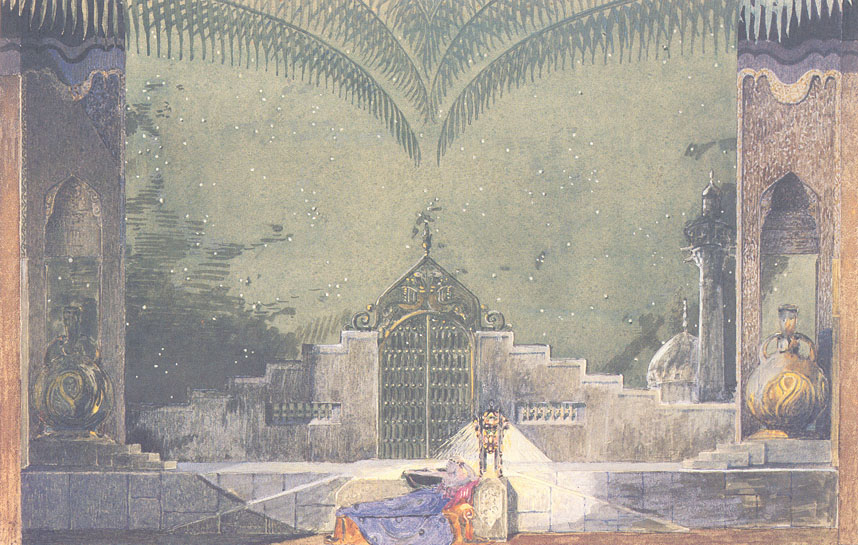

yellow curtains. For Offenbach's Contes d'Hoffmann (fig.

4), Urban eliminated footlights, created a diffused lighting

that seemed to bathe the singers' faces in a natural

glow, and used raised platforms to distinguish the imaginary

tales from the "real" world of the prologue and

epilogue. His Montmartre set for Charpentier's (fig.

19) may strike us today as fairly conventional and painterly,

yet in contrast to the contemporary fare Macgowan saw

it as "pure impressionism." Instead of the usual "impossible

pretense at a city of real mortar and a sky of true azure

depths," he saw "simply a picture into which

fitted music and personages, all in the same new world

of interpreted emotion."27

One of the innovations of the New

Stagecraft was the use of "portals," a device

that Urban essentially introduced to American stage design.

Portals were proscenium-like frames set within the, stage

behind the actual proscenium. They had the practical

effect of narrowing the sometimes massive openings of

many opera house stages to more manageable proportions.

Since the baroque era, designers had employed "sky

borders" or foliage borders – parallel strips

of canvas painted (and sometimes shaped) to resemble

the sky or tree limbs – to hide the fly space and,

later, lighting equipment. It was an accepted convention,

but as an illusion it had long lost its effectiveness.

The portal functioned to restrict sight lines without

pretending to be something it was not. Like the "prosceniums" that

Urban

16

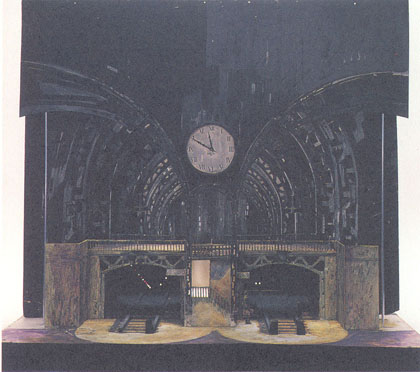

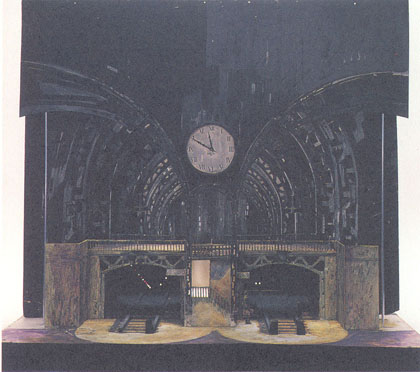

Fig. 21 Jonny

spieltauf, set model, 1929 (cat. 44)

introduced into his various architectural

projects, the portals had the effect of re–emphasizing

the theatricality of the production: they blended the

architectural quality of the actual proscenium with the

artifice of the setting and were thus both scenic and

architectural. Most often the portals were constructed

of canvas stretched on wood frames, but Urban also employed

gauze. By framing a scene in graduated thicknesses of

gauze, he could create an aesthetic distance or a sense

of unreality. This technique is particularly notable

in the rainbow-like triangular arch for Jaromir Weinberger's Schwanda at

the Metropolitan Opera in 1931 (fig. 20) or, less obviously,

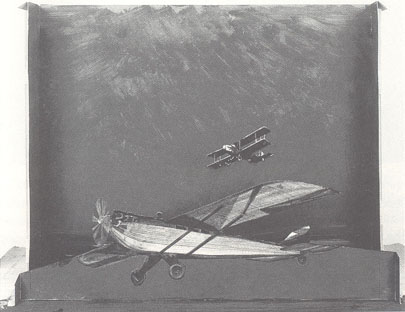

in Ernst Krenek's Jonny spielt auf of 1929 (fig.

21), but can even be seen in the Broadway production Flying

High (fig. 22).

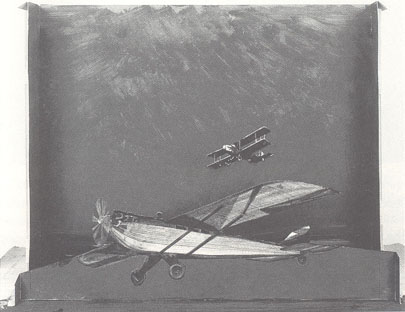

Fig. 22 Flying

High, set model, 1930 (cat. 69)

17

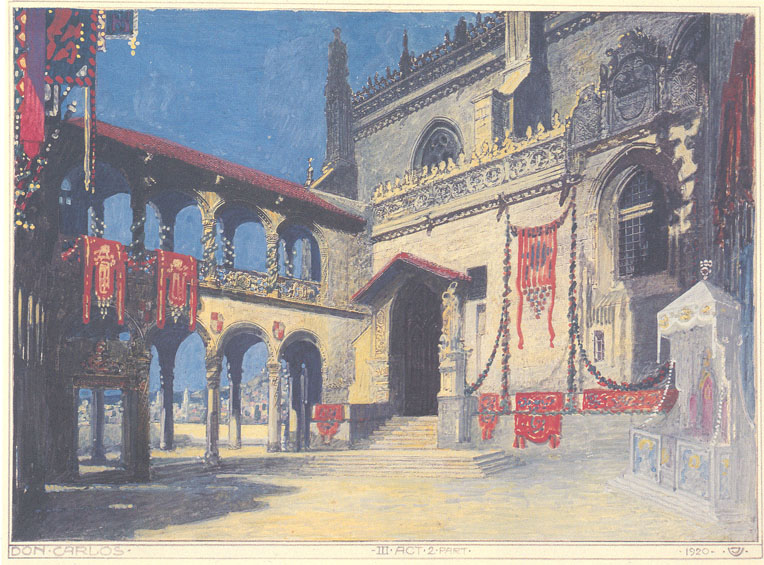

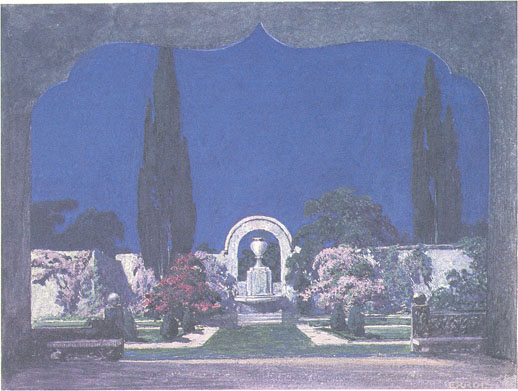

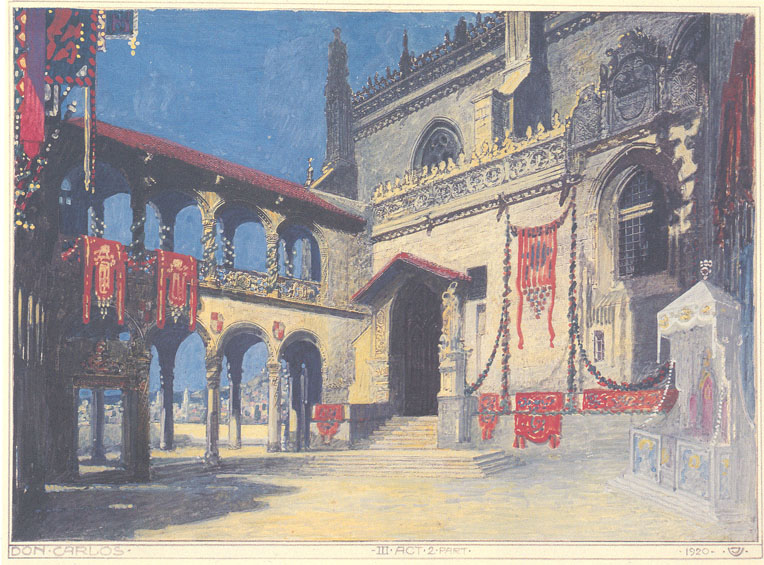

Fig. 23 Don

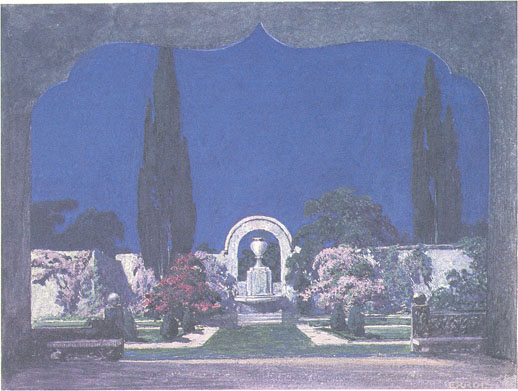

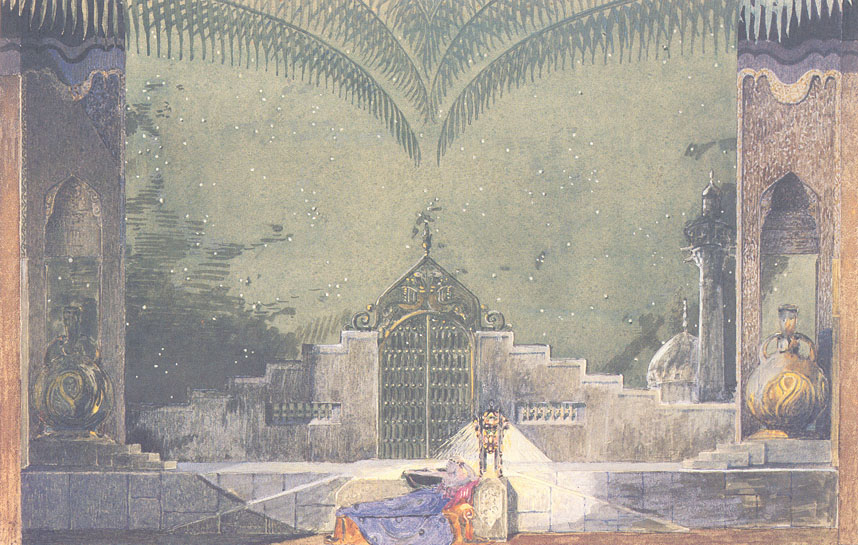

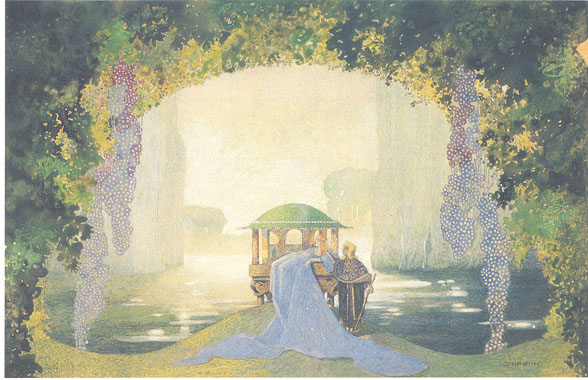

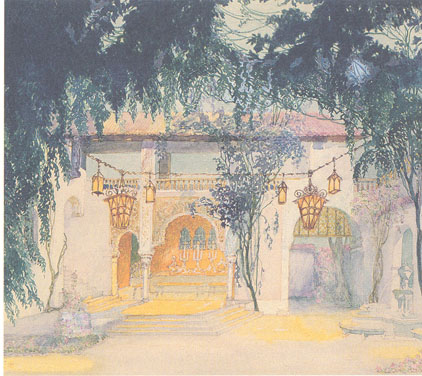

Giovanni, Giovanni's garden, 1913 (cat. 33)

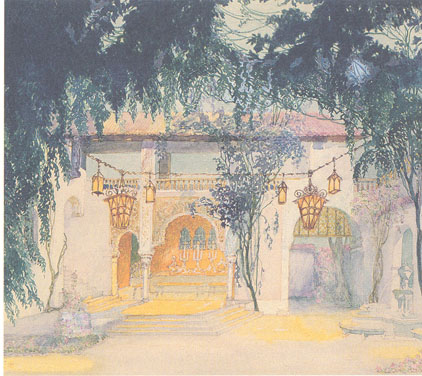

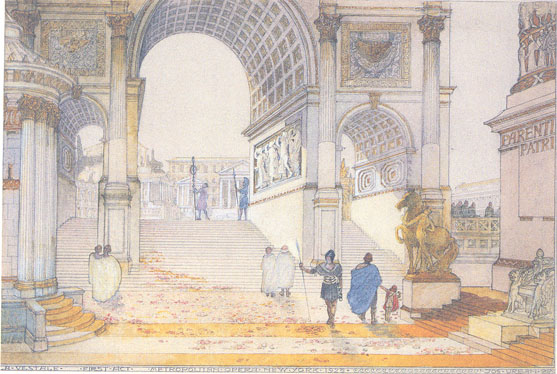

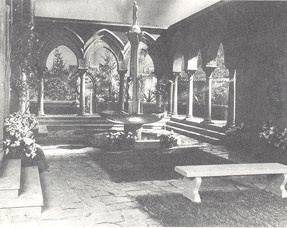

Urban also employed what could be

described as mini-prosceniums within his settings, as

he had within his architecture, to frame scenic vistas.

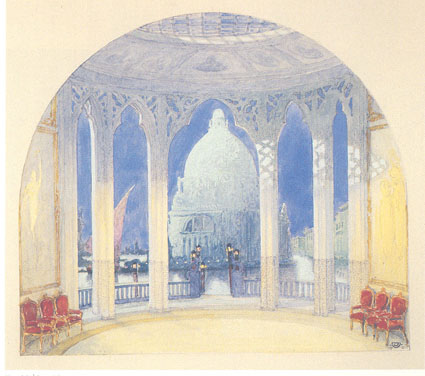

Examples abound but might be noted particularly in the

garden scene of the Boston production of Don Giovanni,

whose Turkish arches framed an Art Nouveau garden and

a brilliant Urban–blue sky (fig. 23), or in Gasparo

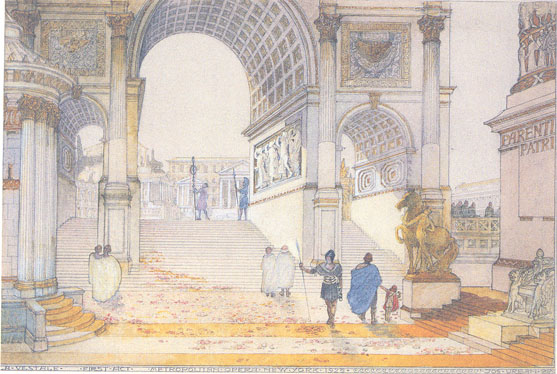

Spontini's La Vestale at the Metropolitan Opera

in 1925 (fig. 24), in which a Roman triumphal arch framed

the Roman city beyond. These portals not only served

as focusing devices but, by allowing the spectator only

a limited view of a vista, suggested a much larger expanse

and far greater detail. The scenes glimpsed through these

arches were, like Shakespeare 's poetic evocations of

scenery, suggestive and thereby allowed the spectator's

imagination to complete the image in far greater detail

than possible with the scene painter's creation.

Urban was not merely the designer,

he was also the stage director for many of the operas

that he worked on – something that may surprise

us. The rising prominence of the director and increasing

specialization of the designer through the twentieth

century has encouraged a separation of these roles. Contemporary

audiences now associate the combined director–

18

Fig. 24 La

Vestale, 1925, watercolor, 8% x 13 in.

Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

[Show

larger image]

designer either with avant–garde

artists, such as Robert Wilson, or the creators of spectacle,

such as Franco Zeffirelli. But early in the twentieth

century, Urban was exercising a significant artistic

control and as such he was able to bring innovations

to the staging and acting while fusing the visual and

performative elements of the opera into a unified whole.

The Boston critic H.T. Parker, an early advocate of the

New Stagecraft, was rapturous in his praise, writing

that in The Tales of Hoffmann, Urban "freed

the singing–players from the outworn conventions

of operatic acting, persuaded them to sink themselves

into their parts and to adjust their parts to the play."28 Parker

went on to prophesy that "some day, the records may

say that a revolution in the setting and lighting of

the American stage dates from the innovations at the

Boston Opera House."29

Two of the primary sources for the

New Stagecraft were the Swiss designer Adolphe Appia

(ten years older than Urban) and the English designer

and director Edward Gordon Craig (born the same year

as Urban). Appia set out to resolve the false dichotomy

between two–dimensional scenery and the three–dimensional

plasticity of the actor. He abandoned illusionistic decor

for the sculptural space of the stage and took advantage

19

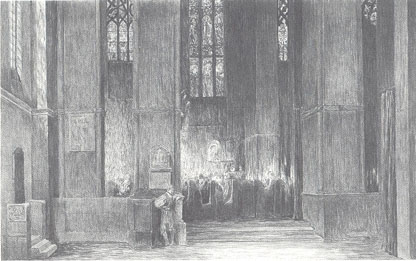

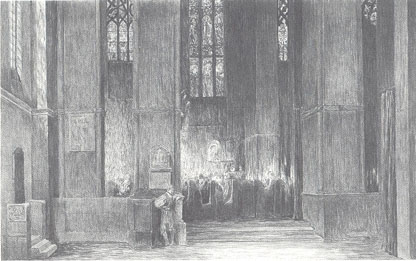

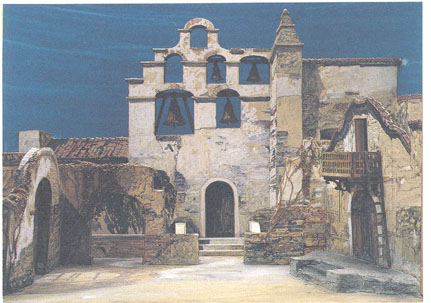

Fig. 25 Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg, inside

Saint Katherine's Church, 1908 (cat. 24)

of the new technology of electric

light to revolutionize stage illumination, literally

sculpting space with light. He did not reject decor altogether,

and particularly in his designs for Wagnerian opera he

created a suggestive and impressionistic style of scenery

that evoked mood more than specific locale. Craig similarly

rejected the trompe–l'oeil stage of the nineteenth

century. His signature contribution was a system of moving

screens that could constantly transform the space of

the stage. His designs often involved towering pillars

and walls that gave his settings a sense of grandeur.

Craig and Appia clearly had an impact

on Urban. As early as 1908 a Craig–like massing

of strong vertical, angular columns and steps can be

seen in Urban's design for Wagner's Die Meistersinger at

the Vienna Opera (fig. 25). But unlike the soaring, almost

gravity–defying semi-gothic creations of Craig,

Urban's early attempt seems earthbound and heavy. A

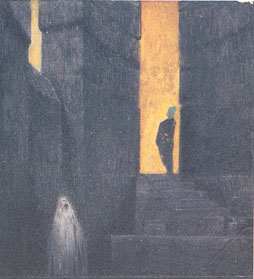

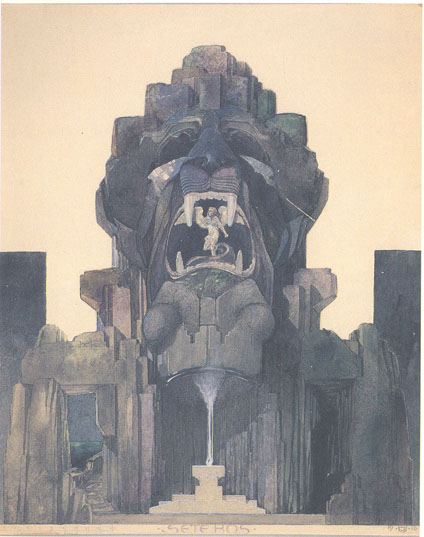

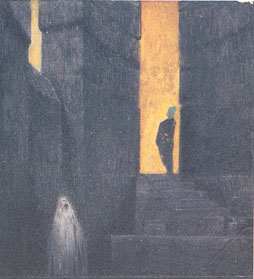

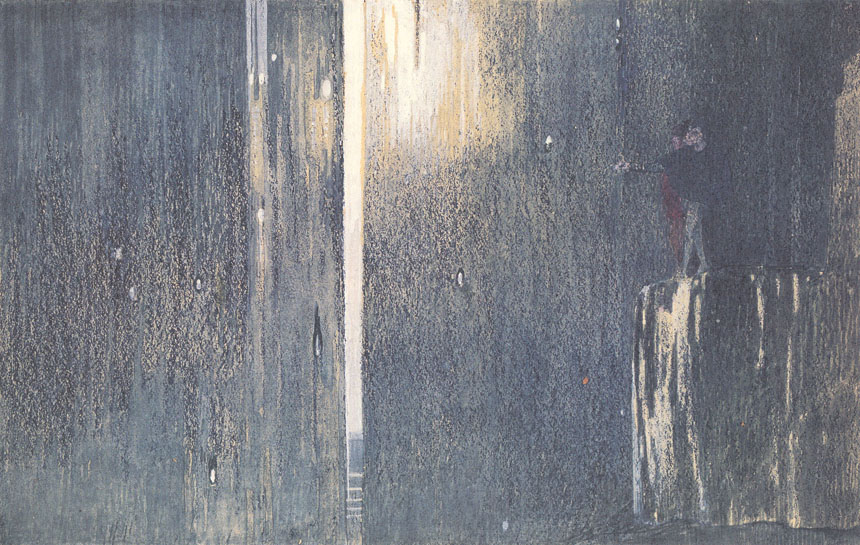

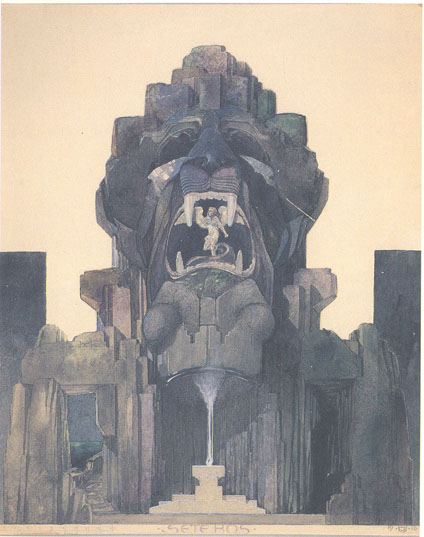

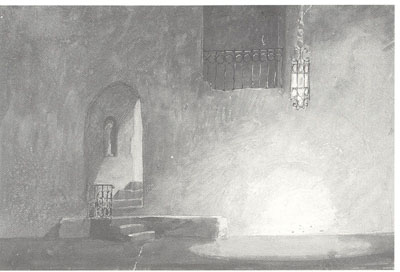

Fig. 26 Parsifal,

Klingsor's magic castle, 1914 (cat. 36)

few years later, a similar approach

was used in his Boston Parsifal (fig. 26). Notably, Urban

the colorist comes through even amidst the shadowy gray

tones inspired by Craig and Appia. A fiery orange sky

is visible through two angular gray columns. Whereas

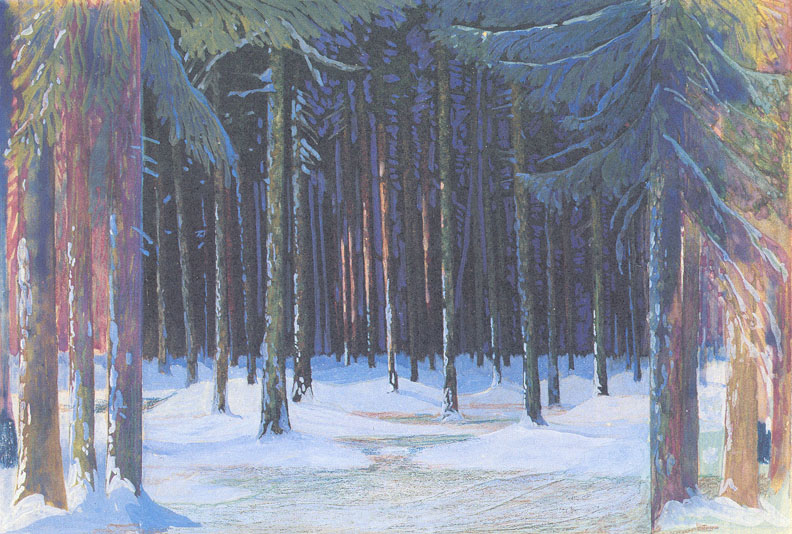

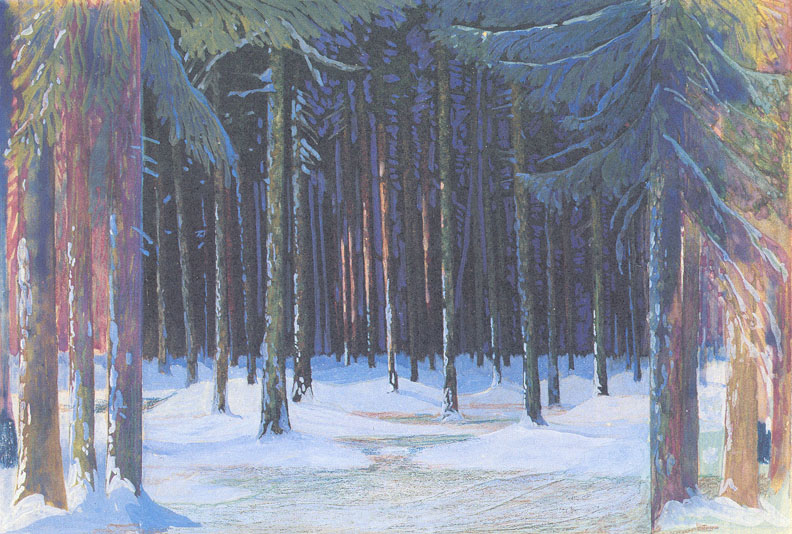

these designs show a presumed influence of Craig, his

sacred forest for Parsifal at the Metropolitan

Opera (fig. 27), produced in 1920, seems to be a virtual

copy of Appia's 1896 rendering of the same scene (fig.

28). This Appian approach to the forest makes a telling

contrast with the forest from act 5 of Liszt's St.

Elizabeth from 1918 (fig. 29) The treatment of the

individual trees is similar, but the massing of them

and the use of color in the latter created something

more akin to Urban's fairytale illustrations.

Several members of the new generation

of American designers at the start of the twentieth century

studied with Appia, Craig, and others in Europe. Notable

among the young Americans were Robert Edmond Jones

20

Fig. 27 Parsifal, sacred

grove, 1920 (cat. 41 a)

[Show

larger image]

Fig. 28 Adolphe Appia, Parsifal, sacred

grove, 1896. Collection Suisse du Theatre, Bern

Fig. 29 St.

Elizabeth, woods, 1918 (cat. 39)

[show

larger image]

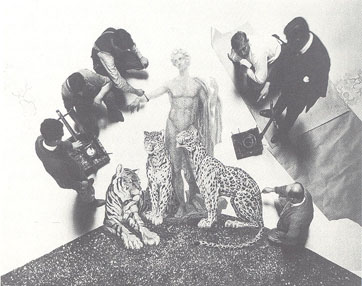

and Lee Simonson. According to the

now accepted history, the first example of the New Stagecraft

to be produced in America was Jones's design for Anatole

France's Man Who Married a Dumb Wife at New

York's Wallack Theatre in 1915 (fig. 30). The play served

as a curtain–raiser for the English director Harley

Granville–Barker's production of George Bernard

Shaw's Androcles and the Lion. Jones's setting,

done in shades of black, white, and gray – like

much of the work of Appia and Craig – used simple

geometric shapes, creating the impression of a wood–block

print, vaguely Japanese in feeling but also medieval.

Because it was done on Broadway and was unlike the standard

Broadway fare, the set received significant press (both

positive and negative), which helped to establish the

apparently new movement and lent credence to the appealing

story of a single production giving birth to a new aesthetic.

The fact is that more than six months earlier, the designer

Samuel J. Hume had mounted a highly touted exhibition

of new European stage design at his studio in Cambridge,

21

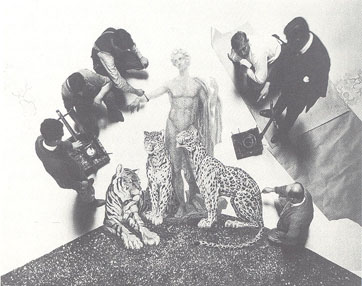

Fig. 30 Robert Edmond Jones, The Man Who Married

a Dumb Wife, revised sketch, 1915.

Whereabouts Unknown

Massachusetts, which was subsequently

mounted in a Fifth Avenue gallery in New York City. More

important, of course, were the three seasons of Urban's

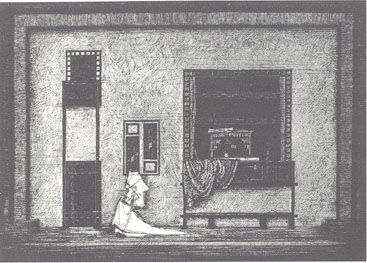

Boston Opera productions. His setting for act 2 of Puccini's Madama

Butterfly (fig. 31), in particular, is remarkably

similar to Robert Edmond Jones's supposedly groundbreaking

design three years later.

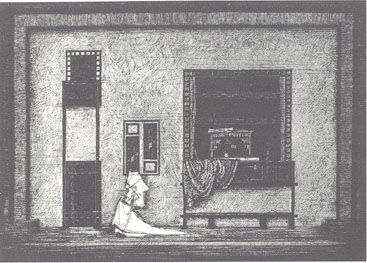

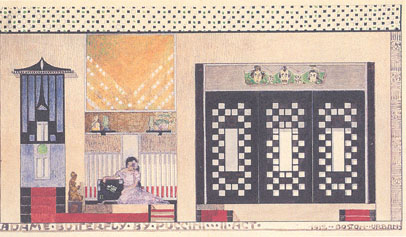

Urban's Madama Butterfly was

composed almost entirely of rectangles surrounded by

a decorative geometrical frame. The arrangement of shapes

was, in essence, a blueprint for Jones's later version.

Urban was strongly influenced by the Wiener Werkstatte – the

Viennese arts and crafts movement with its reliance on

geometric detail and decorative line – and this

production and many others reflect that aesthetic. Werkstatte–like

decor also informs many of Urban's Broadway interiors.

It is instructive to compare the Madama Butterfly to

his fundamentally similar elevation for the Werkstatte–inspired

bedroom in the Redlich Villa in Vienna (fig. 32) with

its surface carved into rectangular blocks offset by

geometric

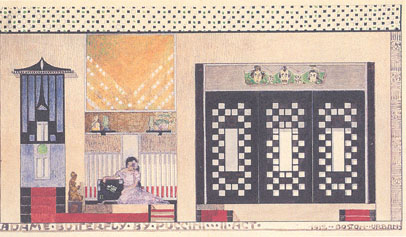

Fig. 31 Madama

Butterfly, inside Butterfly's house (detail),

1912 (cat. 310)

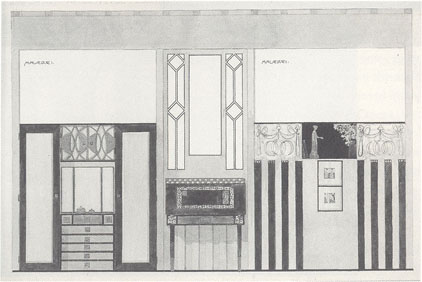

Fig. 32 Redlich Villa, Elsa Redlich's bedroom, 1907 (cat.

6)

22

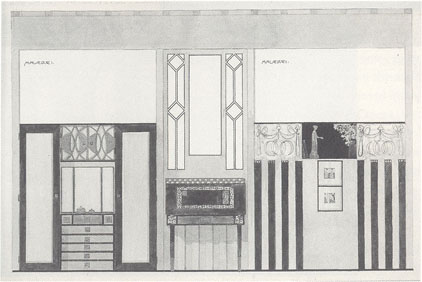

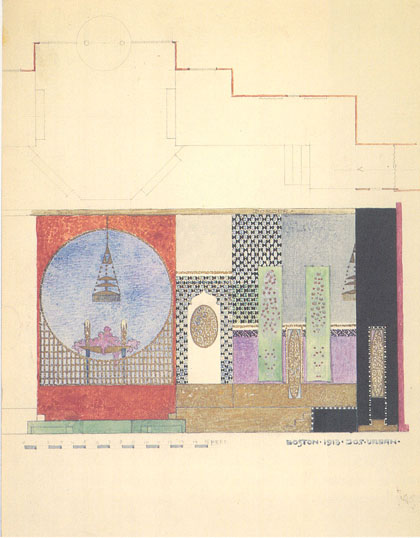

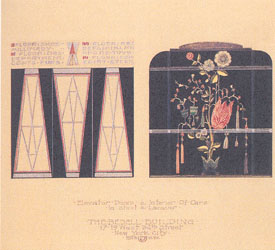

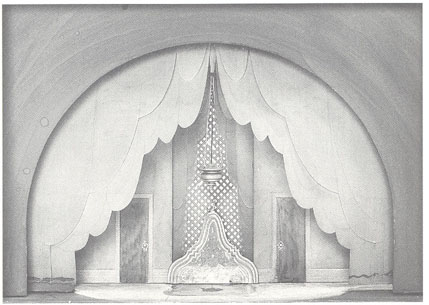

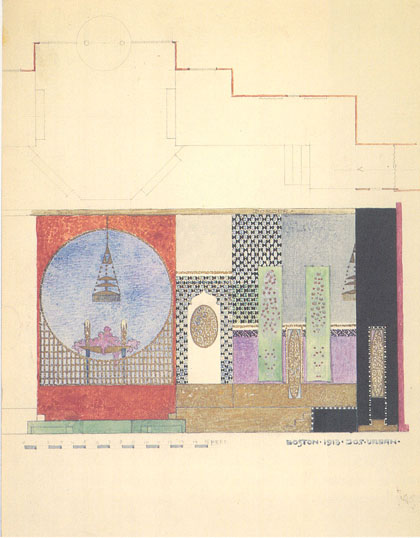

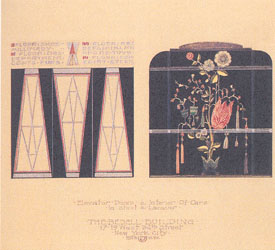

Fig. 33 Djamileh, elevation and ground plan, Haroun's

palace, 1913 (cat. 32)

decorative motifs. The pattern can

be seen again in the 1913 design for Bizet's Djamileh (fig.

33) in Boston. One significant difference between the

Urban and Jones designs is the use of color. The bold

black–and-white checkerboard patterns of the stage

left window unit of Butterfly are surrounded

by a palette drawn from the blue–violet end of the

spectrum, with exclamatory red highlights along the bottom.

Jones introduced color to his setting only through the

costumes.

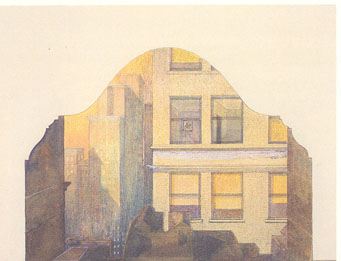

But in 1915, any theater or art done

outside of New York City remained essentially invisible

(and in theater, at least, the situation has not changed

all that much). Urban attracted the attention of the

cognoscenti, but the real recognition ultimately went

to Jones because he was the first to be seen in New York.

COLOR AND ART NOUVEAU

Joseph Urban, first and foremost,

was a colorist. All of his innovations –on the stage,

in architecture, and in decoration – can be tied

to his unprecedented use of color, which was virtually

unmatched in the twentieth century. His appreciation

of color was heightened by his eight–month stay

in Egypt when he was nineteen.

Fig. 34 Fairytale illustration, n.d. (cat. 23)

[MISSING

TEXT] er, Vuillard, Maillol, and

others) valorized color as a tool for emotional communication. "We

can no longer reproduce nature and life by more or

less improvised trompe 1'oeil," declared Maurice

Denis, "but on the contrary, must reproduce our

emotions and our dreams by representing them, using

forms and harmonious colors."32 The

bold, expressive use of color came to dominate a

wide range of arts across Europe at the turn of the

century. It is especially evident in the work of

two artists who had a strong influence on Viennese

developments, Edward Burne–Jones and Ferdinand

Hodler. In Vienna, the symbolist approach to color

was most pronounced in the paintings and decor of

Gustav Klimt, whose use of line, form, and

24

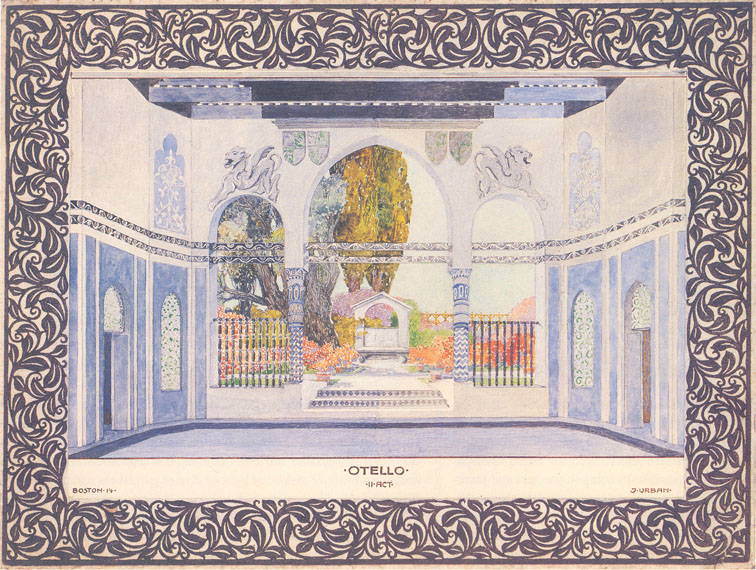

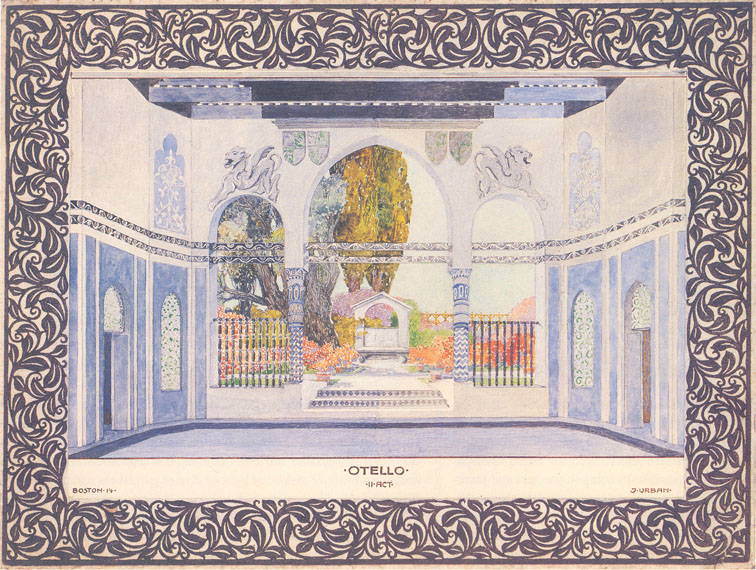

Fig. 35 Otello,

Desdemona's garden, 1914 (cat. 35)

Fig. 36 Parsifal,

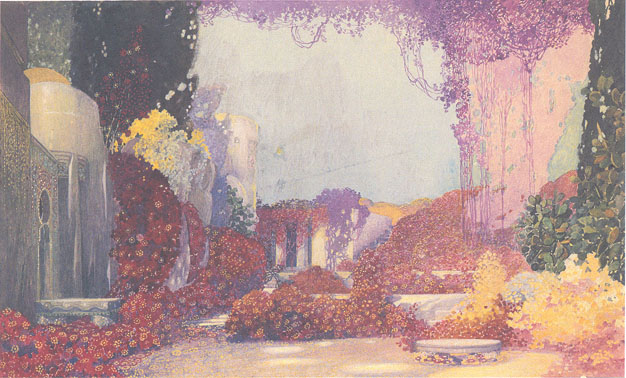

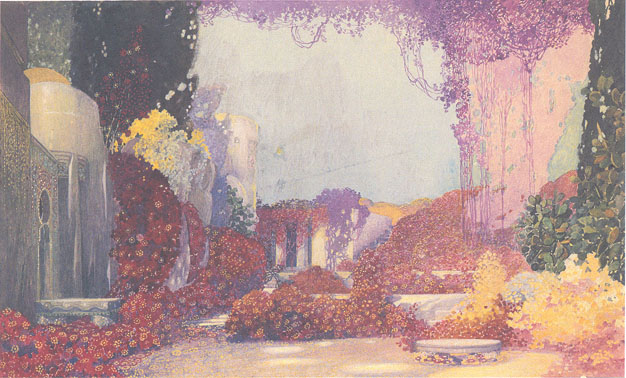

Klingsor's garden, 1920 (cat. 41b)

[Show

larger image]

color seems to anticipate or parallel

Urban's scenic style.

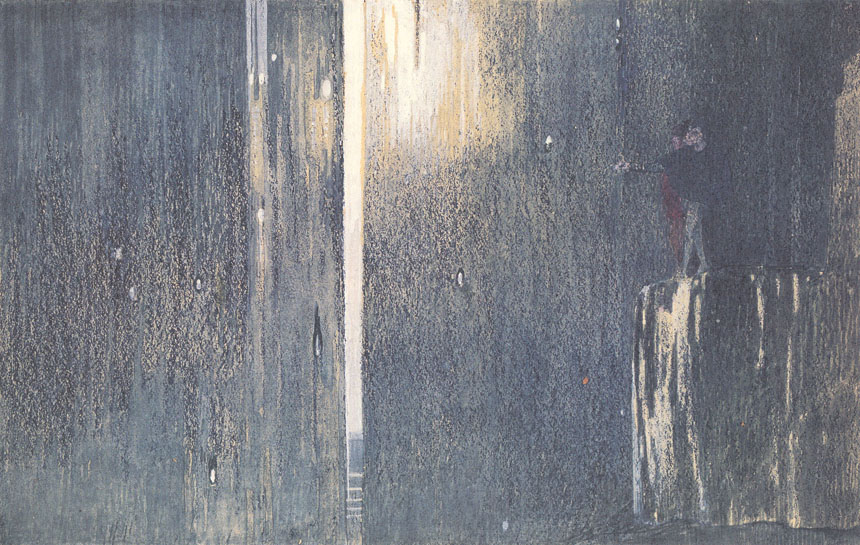

But the artist whose work most clearly

correlates to Urban's in its use of color and technique

is Georges Seurat. The shimmering colors that Urban achieved

on the stage were created through a variation of Seurat's

pointillist technique, which broke up color into its

component parts and juxtaposed complementary colors in

a seemingly abstract mosaic pattern that, when seen in

toto, created a unified image. Urban can be seen using

this technique early on, in one of his book illustrations

(fig. 34) in which the "points" of color are

quite pronounced. Urban painted scenery not as an illusionist

imitation of nature but, as one writer put it, "as

a medium for the reception of colored light."33 Urban

understood that color on the stage (as opposed to on

an artist's canvas) is a result of the particular combination

of paint pigments and stage lighting – red pigment,

for instance, becomes visible only under red light or

the red part of the spectrum within "white" light.

Thus, instead of covering a canvas with flat expanses

of paint as had been the practice of most scene painters,

Urban took a semi–dry brush and spattered it. For

his skies, for example, he used several shades of blue

spattered over each other, then further spattered the

canvas

25

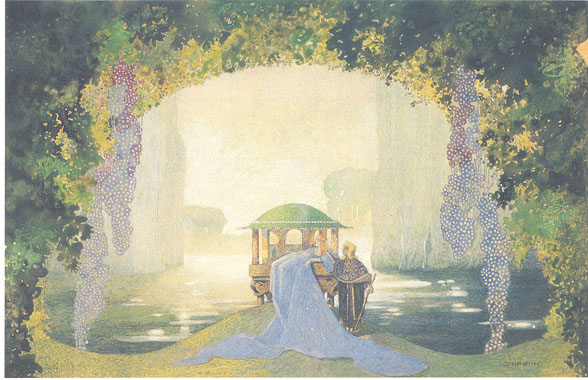

Fig. 37 The

Garden of Paradise, queen's bower, 1914 (cat.

47)

[Show

larger image]

with red, green, and silver.34 In

the scene shop, under work lights, the resultant painting

looked gray, but on the stage colored light employed

with subtlety picked up and reflected the differing flecks – Urban

could create anything from dawn to moonlight. The effect

was "as suggestive of reality," claimed Macgowan, "as

is any painting by Monet."35 The fragmented

palette created a luminous, shimmering effect that repeatedly

evoked the word "magical" from critics and observers.36

.

Urban's palette was not limited to

blue, nor was his technique limited to pointillage. As

with his Jugendstil or Art Nouveau colleagues, he drew

upon the brilliant colors and undulating forms of exotic

flowers and foliage, the mysteriously patterned world

seen through the microscope, and other enigmatic examples

of nature; there was also a distinct influence of Japanese

prints and other Asian forms. This could be seen over

and over in his repeated use of dripping foliage, as

in the garden viewed through the portals of Verdi's Otello at

Boston in 1914 (fig. 35); the ultimately unused garden

for the Met's 1920 Parsifal (fig. 36); and The

Garden of Paradise designs (fig. 37); as well as

the murals of the Ziegfeld Theatre (fig. 38) and the

murals and ceilings of many restaurants and hotels, such

as the

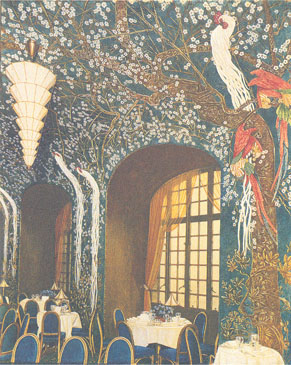

26

Fig. 38 Ziegfeld

Theatre, mural for balcony ceiling, 1926–27

(cat. 9c)

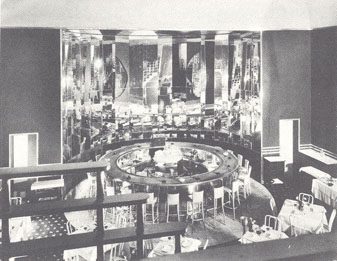

St. Regis Hotel roof garden (fig.

39), the Central Park Casino, or the elevators of Bedell's

department store (fig. 40). These designs used a dizzying

array of pastels and drew heavily from the red and violet

end of the spectrum. Such a palette was alien to the

turn–of-the-century naturalists and literalists,

and was seemingly anathema to the Jones–Simonson

school of New Stagecraft with its monochrome palette.

Related to Urban's use of color was

his sensuous treatment of line. With precedents in the

arts and crafts movement and symbolism, and with a conscious

nod toward medieval art and orientalism, Art Nouveau

was

Fig. 39 St.

Regis Hotel, New York, murals for roof garden dining

room, 1927–28 (cat 10)

typified by a provocative and decorative

use of line – "line determinative, line emphatic,

line delicate, line expressive, line controlling and

uniting" as Walter Crane, an artist influenced by

William Morris, put it in 188937 – which

functioned visually much as sound had in symbolist poetry.

Line, as the art historian Peter Selz explained, "became

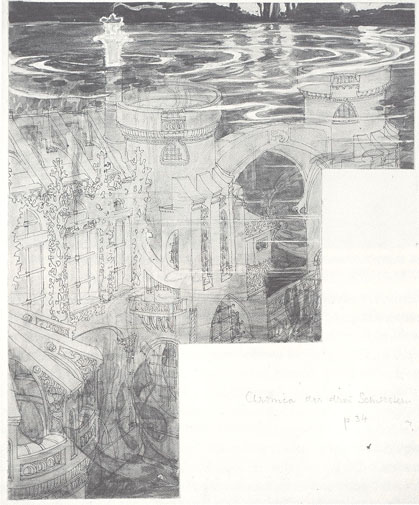

melodious, agitated, undulating, flowing, flaming."38 Such

adjectives well describe the sinuous lines of many of

Urban's illustrations from the 1890s, most done in collaboration

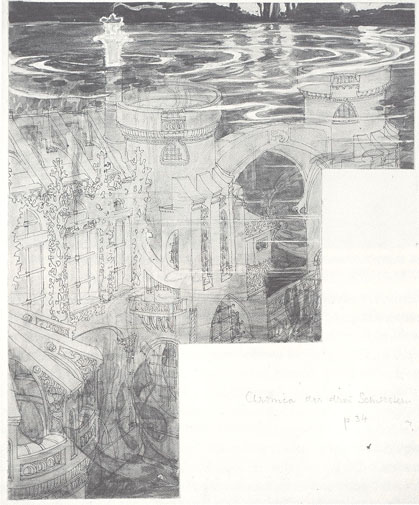

with his brother–in-law Heinrich Lefler, as in the

underwater castle image in Chronika der drei Schwestern (Chronicle

of the Three Sisters)

27

Fig. 40 Bedell

Store, elevator doors and interior of cars, 1928

(cat. 12b)

from 1899 (fig. 41). This use of line

is a crucial element in his drooping foliage patterns

and murals, recurs constantly in various Follies productions,

and emerges rather startlingly in the Aubrey Beardsley–like

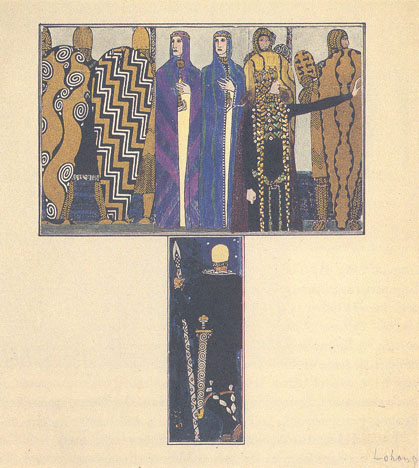

tableau curtain of "Tinturel's Vision" for the

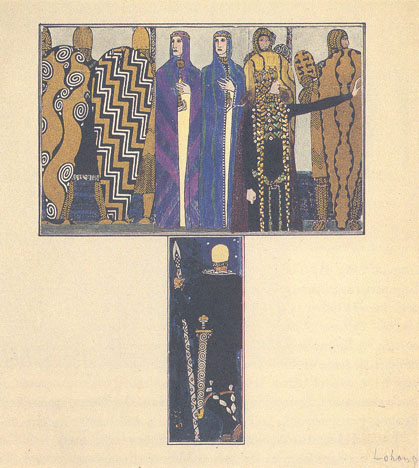

Met's Parsifal (fig. 42) or the Erte–like

curtain for Lohengrin (fig. 43). With the exception

of some Ballets Russes designs, such use of line was

rare on the stage throughout this period except in the

work of Urban. It was particularly striking when juxtaposed,

as it sometimes was, against the geometric forms of the

Werkstatte–inspired designs.

The complete marriage of line and

color, not surprisingly, found its most triumphant form

in Urban's architecture; and nowhere was this more brilliantly

demonstrated than in the Ziegfeld Theatre. As Urban himself

characterized it, it was to be a place where "people

coming out of crowded hours and through crowded streets,

may find life carefree, bright and leisured."39 The

interior was designed with no moldings so that everything

would flow together smoothly, "like the inside of

an egg," and the

Fig. 41 Chronika der drei Schwestem, 1899 (cat.

2)

28

Fig. 42 Parsifal,

tableau curtain showing "Tinturel's Vision," 1920,

watercolor, 12 x 16 3/8 in.

Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

[Show

larger image]

decor was envisioned as a single,

unifying, encompassing mural. "The carpet and seats," explained

Urban, "are in tones of gold, continued up the walls

to form the base of the mural decoration where heroes

of old romance form the detail in flowering masses of

color interspersed with gold." For Urban this was

not merely decoration, however, but a carefully thought–out

scheme for enhancing the experience of the spectators – focusing

them on the stage during the performance and bathing

them in warmth during intermissions. "The aim . .

. was to create a covering that would be a warm texture

surrounding the audience during the performance. In the

intermission this design serves to maintain an atmosphere

of colorful gaiety and furnish the diversion of following

the incidents of an unobtrusive pattern." This design

scheme was as much an example of architectural gesamtkunstwerk as

Wagner's opera house at Bayreuth, perhaps even more so.

Because it was now employed in the service of popular

Fig. 43 Lohengrin,

curtain, 1909–11 (cat. 25)

29

entertainment, however, it was never

accorded the same status or respect. (Interestingly,

just as Wagner hid the orchestra from view so as not

to detract from the idealist vision created on the stage,

Urban hid his equivalent of the orchestra: the lighting

equipment. Light was crucial in bringing his creations

to life and in giving movement to the architectural forms,

but in both interiors and exteriors, the sources of illumination

remained hidden so as not to seem like afterthoughts

or to interfere with the desired effects.)

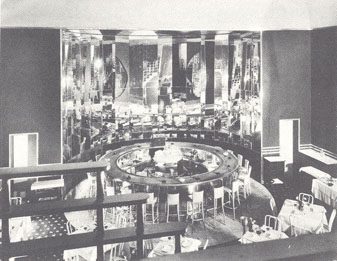

By contrast, Urban's Paramount Theatre,

a movie house in Palm Beach, Florida, was simple in its

lines and employed a subdued palette of silver and green, "cool

and comfortable" (fig. 55). The rationale was simple:

the rhythms of Palm Beach were "leisured and sunny" as

opposed to those of New York City. "The theatre," explained

Urban, "is not an escape from the life around, but

a part of it, fitting into the rhythm of the community.

The architecture of the Paramount Theatre ... is accordingly

simple, spacious, Southern."

Urban was a forceful advocate for

the use of color in architecture – to

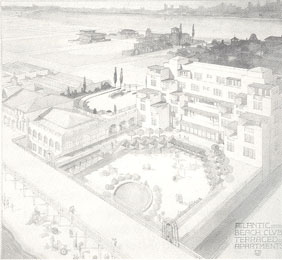

Fig. 44 Atlantic

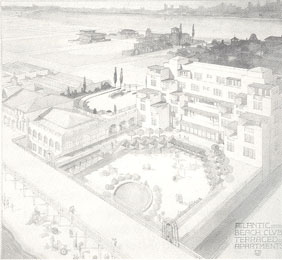

Beach Club, Long Island, terraced apartments, 1929-31

(cat. 20)

shape the mood and enhance the functions of interiors,

and to transform entire cities through the application

of color to exterior surfaces. Urban, in fact, saw cities

as virtual stage settings, which needed color to bring

them to life. "When the morning sun gilds the city

and casts blue shadows," Urban wrote in 1927,

even the buildings of

neutral coloring are often very beautiful, but there

are many hours when these effects are not seen and there

are gray days. Then our buildings need positive colors

to enliven them. When we look at the city at night, we

see light in many tones. Some are dazzling white, others

are soft and warm. A building can have the same distinctiveness

in the daytime. Its color can express its personality.

These colorful structures will have charm on gloomy days

as well as when the sunlight tints them, and at night

all degrees of the lights and shadows of artificial illumination

will have their part in modifying and enhancing them.40

The Atlantic Beach Club (1929–31)

on Long Island was an example of this approach (fig.

44). The walls and decks were composed of surfaces of

red, yellow, blue, and white stucco which served as a

background for brilliantly colored awnings and umbrellas.

By the 1930s Urban was moving into bolder experiments

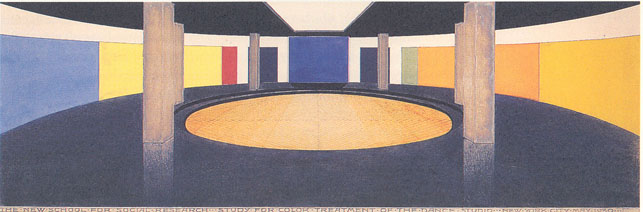

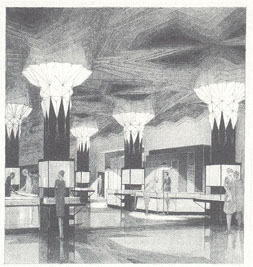

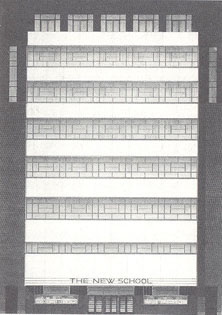

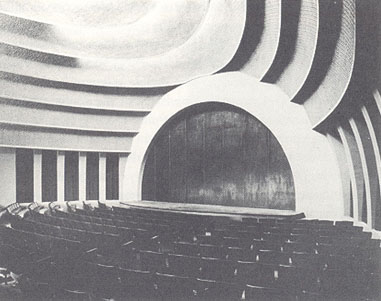

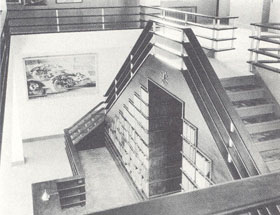

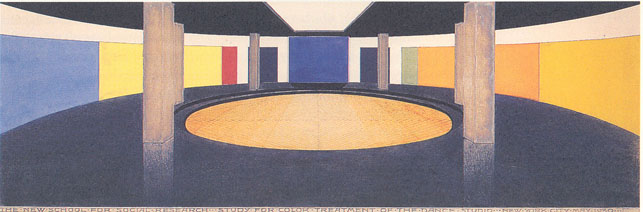

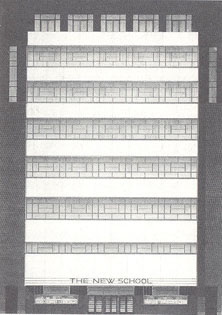

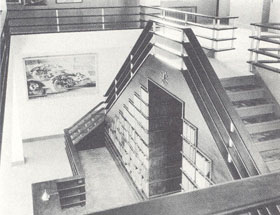

with architectural color. The interior of the New School

for Social Research's new home on West 12th Street in

New York City (fig. 45), which opened in 1930, provided

a particular challenge – a large number of rooms

and auditoriums in a relatively small space with each

room having a specific function. Urban used large masses

of bright color on plaster surfaces to establish relationships

among the spaces while distinguishing them as necessary. "The

color is in fact the form, the volume," observed

the architect Otto Teegen. "One does not feel that

certain architectural surfaces have been painted, but

that these architectural planes and volumes are actually

color planes and color volumes which have been composed

to make a room or a library, as the case may be."41According

to Urban, warm colors were located

30

where they receive the

most light, cold where there is most shadow, a change

of plane is generally emphasized by a change of color,

thus the walls have one set of colors, the ceiling another.

By thus modeling the wall surfaces of a room the boxlike

property of four walls is given an expression of contrasting

filled spaces and void space; the monotony of the enclosing

areas is transformed to an imaginative statement of the

space enclosed and given a character by the emotional

statement of color.42

It was the critic Edmund Wilson who

this time criticized the building for its theatricality. "When

he tries to produce a functional lecture building," complained

Wilson, "he merely turns out a set of fancy Ziegfeld

settings which charmingly mimic offices and factories

where we keep expecting to see pretty girls in blue,

yellow and cinnamon dresses to match the gaiety of the

ceilings and walls."43

Building on the New School experience,

Urban saved his boldest architectural color work for

what was to become the last project of his life, the

International 1933 Century of Progress International

Exposition in Chicago, for which he was appointed director

of exterior color and consultant on lighting. His plan

seemingly amalgamated the Nabis approach of saturated,

emotion–charged colors with Bauhaus-like surfaces

of geometric planes (fig. 46). He aimed to create a unified

approach to color for the entire fair – color as

an architectural medium, not decoration. He set out six

guiding principles:

- Color to be used in an entirely

new way.

- Color used to co–ordinate

and bring together all these vastly different buildings.

- Color to unify and give vitality.

- Color to give brightness and

life to material not beautiful in itself.

- Color to give the spirit of carnival

and gaiety – to supply atmosphere lacking in our

daily life.

- Color that should transport you

from your everyday life when you enter the fairgrounds.44

He created a palette of twenty–four

colors, all of the "brightest intensity": 1 green,

2 blue–greens, 6 blues, 2 yellows, 3 reds, 4 oranges,

2 grays, white, black, silver, and gold. The plan was

for approximately 20% of all surfaces to be white, 20%

blue, 20% orange, 15% black, and the remaining 25% to

be spread among the yellows, grays, greens, and silver.45 It

is one thing, of course, to create such a bright and

vibrant color scheme for a world's fair, quite another

to transform a functioning city.

Fig. 45 The

New School for Social Research, New York, dance studio,

1930 (cat. 19c)

31

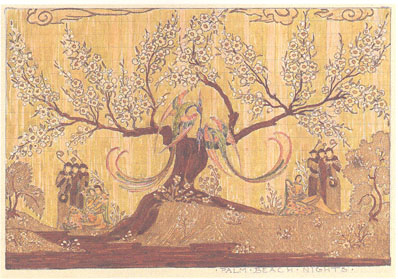

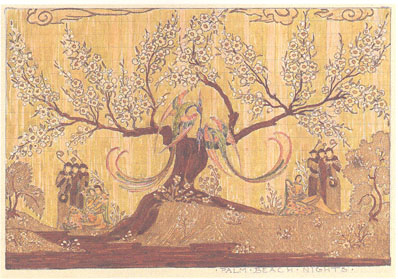

ZIEGFELD FOLLIES

Despite his numerous brilliant productions

for the Metropolitan and Boston operas and despite his

major architectural works, Urban became – and remains

- best known for his work with Florenz Ziegfeld.

Following the closing of the Boston

Opera, Urban went to Paris with the company in July 1914

to direct Wagner's Tristan und Isolde – the

first German opera presented there in thirty years – but

the outbreak of the war stranded him in Europe. The producer

George Tyler, however, managed to bring him back to New

York to design a production of Edward Sheldon's Garden

of Paradise, which became Urban's first Broadway

show. The production itself was a failure, but Urban's

sets and new aesthetic attracted attention. The nine

fantastical scenes included a castle, a storm at sea,

a fairy bower, and a sequence under the ocean. In a contemporary

article on the production, the writer Louis DeFoe seemed

to understand that the New Stagecraft had arrived:

Fig. 46 Century of Progress International Exposition,

Chicago, 1933, watercolor, 13 x 33 in. Rare Book and

Manuscript Library, Columbia University

But the scene changes were unwieldy

and necessitated close to an hour's worth of intermissions,

which contributed to the demise of the show. With the Follies,

at least, Urban would never make that mistake again.

He learned how to make scenery move as if it were music.

Among the few people who saw The

Garden of Paradise was Florenz Ziegfeld, who was

looking for a designer to give the annual Follies (which

had premiered in 1907) a more sophisticated look. He

hired Urban – who had never seen the Follies – and

took him out to Indianapolis to catch up with the 1914

edition on tour. Urban's first – and accurate

- impression was that the show was little more than

a series of disconnected sketches which were equivalent,

in his words, to "advertising posters." He

was going to bring his gesamtkunstwerk approach

to Ziegfeld. "I hope most of all to unify the impression

of all these short scenes, to give the entire evening

a kind of keynote," he declared.47 The Ziegfeld

Follies of 1915, Urban's first, astounded audiences,

in part because of the lavish settings for its twenty–one

scenes, but just as important for the way in which

those scenes flowed from one to the next so that the

entire revue seemed to be a single, unified entity.

One of the techniques that Urban had to master was

the basic vaudeville device of the "in one" scene – an

interlude played in front of a downstage drop curtain

that allowed large set changes to occur behind it.

Some critics bemoaned the fact that a great opera designer

was descending into the lower depths of crass commercial

and mass entertainment,

32

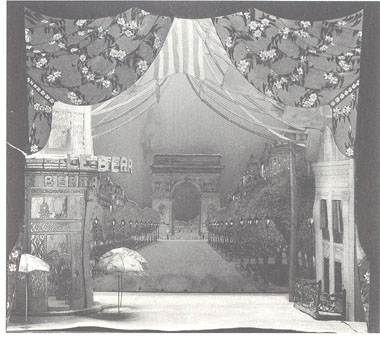

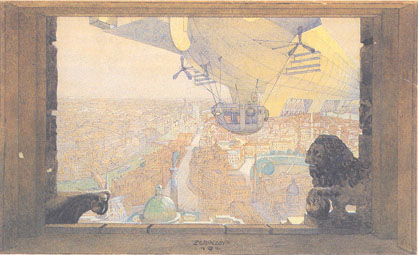

Fig. 47 The Ziegfeld

Follies of 1915, bath scene (cat. 49c)

[Show

larger image]

Fig. 48 The Ziegfeld

Follies of 1915, zeppelin over London (cat.

49b)

[Show

larger image]

Fig. 49 Macbeth,

outside the castle, 1916 (cat. 53)

[Show

larger image]

forgetting that opera had evolved

in large part from baroque intermezzi – the lavish,

allegorical spectacles created by leading architects

and painters of the seventeenth century using fundamentally

the same staging techniques as modern revues and extravaganzas.

History had merely come full circle. (One wonders about

the potential effect on twentieth–century theater

if Appia, Jones, or Bakst had been forced to master and

absorb the ancient crafts and techniques of popular scenography.)

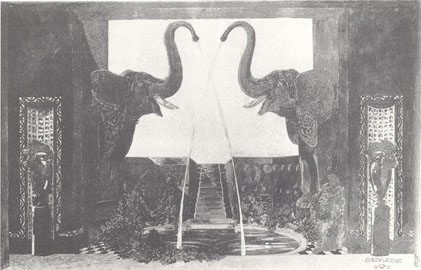

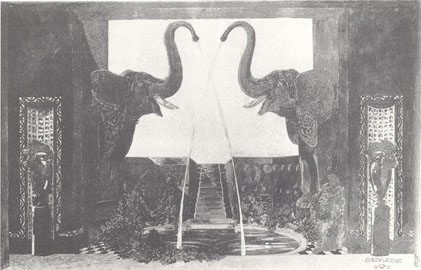

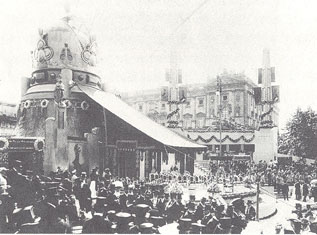

The 1915 Follies included

one of the most spectacular Ziegfeld scenes to that time – the

bath scene (fig. 47), in which two smiling, golden elephants

spouted water from their raised trunks into a pool of

water surrounded by Jugendstil–like shrubbery. Kay

Laurell as Aphrodite rose out of the pool to signal the

start of a mermaid ballet. The staircase behind the pool

was also the first hint of the soon–to-be-famous

Ziegfeld staircase that would showcase the chorus of

Ziegfeld girls. The staircase became

33

central element in The Century

Girl, produced by Ziegfeld and Charles Dillingham

and designed by Urban at the Century Theatre the next

year, and then appeared regularly in the Follies thereafter.

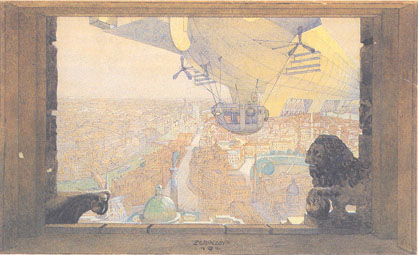

The 1915 Follies was also to contain the stunning

drop of a zeppelin hovering over London (seemingly,

though impossibly, viewed from St. Paul's Cathedral)

(fig. 48) for a skit with the comedians Bert Williams

and Leon Errol. The skit was originally to be in a

submarine, but after more than a dozen rewrites, which

was typical of the Ziegfeld process, the setting was

changed to a zeppelin, and finally the whole thing

was cut during out–of-town tryouts.48 Although

Urban provided the Follies with a sense of

visual style and lavishness that was unsurpassed, as

well as an all–important artistic unity, his designs

were capable of overwhelming the whole production,

even with its enormous star power. A review of the

1917 Follies praises Urban's sumptuous settings

and notes that in his "Oriental setting, [he] has

outdone himself in his employment of colors and seemingly

massive structures," but goes on to protest that

while in richness of

tone and in suggestion of distance the setting is superb,

it, nevertheless, obtrudes upon the players in the foreground.

There is no personality definite and dominant enough

to stand against it successfully, and therefore most

of the fun and satire that had been contrived for the

scene went for naught.49