October 7, 2013 |

BREAD. REDISCOVERED SILENT MASTERPIECE. |

| |

At the end of the 1920s, Mykola Shpykovskyi was one of the leading Soviet directors of comedies. His satires on NEP philistinism were trenchant and cutting. Like many experimental Russian directors who fell under unofficial interdiction in the Russian SSR with Stalin's rise to power, Shpykovskyi returned to Ukraine, which, thanks to the efforts of the then minister of education, Mykola Skrypnyk, was still free of ruthless censorship. Back in Odesa (he had graduated from Novorossiya University in 1917), Shpykovskyi filmed the comedy Three Rooms and a Kitchen (1928) and then a year later his most noteworthy work, Self-Seeker, at the newly built Kyiv film studio. With the proclamation of a course towards collectivization and industrialization, there was no place for pure comedies: the Bolsheviks had an acute need for ideological films based on themes prescribed by the party.

Shpykovskyi adroitly made films that the Soviet sensors wanted to ban right away. In September 1930 his film Bread was taken out of distribution just three days after the premier. Initially, the film was highly praised. In fact, just six weeks before it was banned, the magazine Kino wrote, "Bread doesn't stagger like Arsenal. It simply sings about that which is and must be sung about today. It strengthens and artistically assimilates the achievements of the pioneers. It cultivates and encourages the young sprouts of our cinema. Herein lies its serious mission and great, especially necessary now, cultural achievement." Translating from the Soviet-bureaucratic newspeak this means: "the film is hardly an ideological blessing and is thus worth the money spent on it."

|

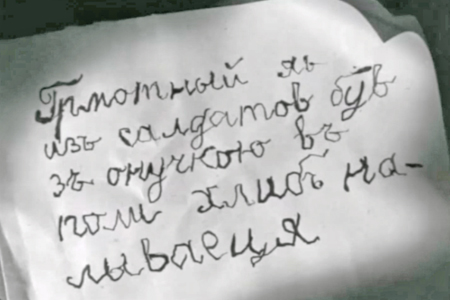

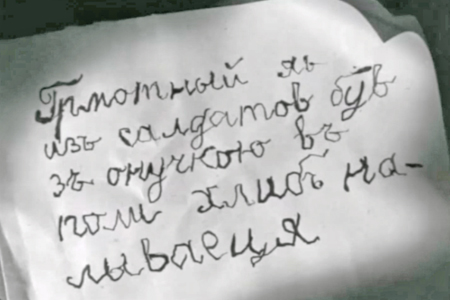

| Bread features the Ukrainian language of the 1920s. |

The magazine Kino was indeed a mouthpiece of VUFKU, the very same VUFKU that financed the shooting of Bread and now was trying to get it approved for all-union distribution via Moscow. The magic of the printed word had no effect on the Central Repertory Committee (the censorship organ of the Soviets). The comrades in Moscow forbade them to show the movie, saying, "The picture gives the wrong impression of the fight for bread. The average Joe is completely absent from the film. The period of restoration (the restriction of the kulak), relative economic retrenchment of the kulak (New Eeconomic Policy), class struggle, the preparation of the political preconditions for the liquidation of the kulak and collectivization (industrialization)—all of this is absent from the movie." Such wording means little to a contemporary person, and besides, it's not quite frank. Since Bread was dedicated the events of the first years after the revolution—and neither to total collectivization nor to the complete liquidation of kulaks—there was no question as to its fate. Actually, the film was banned for another reason, one that the censors were embarrassed to say out loud.

It was not possible to put forth any artistic challenges to Bread. It was simply wonderfully made. The camerawork of Oleksii Pankratiev impresses with its thorough polishing of each frame; there are even barely noticeable shadows at play in the background. The actors perform like gods: both Luka Liashenko and Fedir Hamalii execute their roles without the least overacting that so characteristically plagues silent films. It is a balanced and well-weighted film.

The plot line is very simple: a Red Army soldier, Luka, returns to his home village after the civil war and begins establishing a collective farm. The land for this farm is taken from the villagers, that is "kulaks," the grain for the sowing from the urbanites. The principal conflict occurs as a result of the struggle with the kulaks. The main character also has a standoff with his own father. The old man doesn't believe that the stolen grain will take on the stolen land, but when it begins to grow, he converts to his son's side, evidently convinced that written and unwritten rules can be broken for the sake of the common good. Bread shows the Sovietization of the village very cruelly and honestly, yet from the perspective of the Soviets themselves. Somehow, though, the movie almost turned out anti-Soviet even though this certainly wasn't a goal of the creators.

Shpykovskyi's film was shot, edited, and released at practically the same time as Dovzhenko's Earth. They have the same principal conflict, the same actors (Luka Liashenko is the main character in Bread and the young kulak in Earth), and, what's more, some of the scenes in the films coincide frame-by-frame in both content and composition! Yet Shpykovskyi couldn't have copied Dovzhenko—Bread was already finished in December 1929 when Earth was in the thick of editing. Oleksandr Dovzhenko likewise was the virtuoso who would not stoop to plagiarism. Nevertheless, the films turned out to be similar in many ways just like their nearly identical fates: they were both banned. Collectivization ended up being so terrible that it simply was not possible to make accurate artistic, and at the same time Marxist-Leninist, films about it.

Later in the fifties, Earth became part of the official iconostasis of Soviet cinema, after all—in great part thanks to its wild success in Europe. But Bread seems to have been lost against the backdrop of Dovzhenko's masterpiece. For over eighty years, the movie lay in the archives forgotten by everyone. Even among film historians, not all knew that it existed. And now it is finally being returned to viewers. For the first time in eighty years, the film, newly restored at the National Oleksandr Dovzhenko Center, was shown to the public at the Silent Nights 2013 festival in Odesa.

Adaptation and translation from the Ukrainian by Ali Kinsella

|