Shaping Wildlife: Animal Art in the Early Days of the Bronx Zoo

By Madeleine Tompson, Archivist, Wildlife Conservation Society

“Intrepid are the artists who dare the wrath of wild beasts in the New York Zoological Park.”

So proclaimed a 1906 New York Tribune feature on the artists—Anna Hyatt among them—who studied their subjects at the New York Zoological Park, or Bronx Zoo, as it became more commonly known. To be sure, any work involving wild animals can be dangerous. Hyatt herself had once been knocked down by an elephant—although, as the article acknowledged, that had been at another zoo. In fact, while officials at the Bronx Zoo could never guarantee the behavior of the animals in their charge, they set a new precedent for accommodating and encouraging artists working at the Zoo.

Most prominently, this accommodation took the form of a workspace dedicated for artists’ use in the original construction of the Lion House. Debuting on July 9, 1903, five months after the Lion House’s opening, the artists’ studio realized a vision that dated nearly to the beginning of the New York Zoological Society (NYZS), the organization that founded the Bronx Zoo and that is known today as the Wildlife Conservation Society. The Society’s first annual report, in 1896, included a proposal from the popular wildlife illustrator Ernest Thompson Seton, who set forth the need for accommodations for artists in zoological parks. This need, he noted, was not met in any existing American zoo nor even in any European one. As Seton argued, while many zoos afforded special spaces and privileges to those studying zoology, animals artists of the era—who also flocked to zoos to observe living animals they could not otherwise see—were treated no better than the average visitor, beholden to regular operating hours and forced to contend with the “nuisance of the weather, and the still greater nuisance of the public.” As Seton put it in the following year’s annual report, “What would a microscopist, a writer or a mathematician think if he had to do his work exposed to the weather, and surrounded by a jostling rabble of unmannerly persons! Surely an artist’s work requires his whole attention as much as does that of the classes named.” Indeed, contra the Tribune’s sensationalizing, by several accounts of animal artists working in zoos at the time, it wasn’t the “wild beasts” they feared as much as the crowds of visitors disturbing their work.

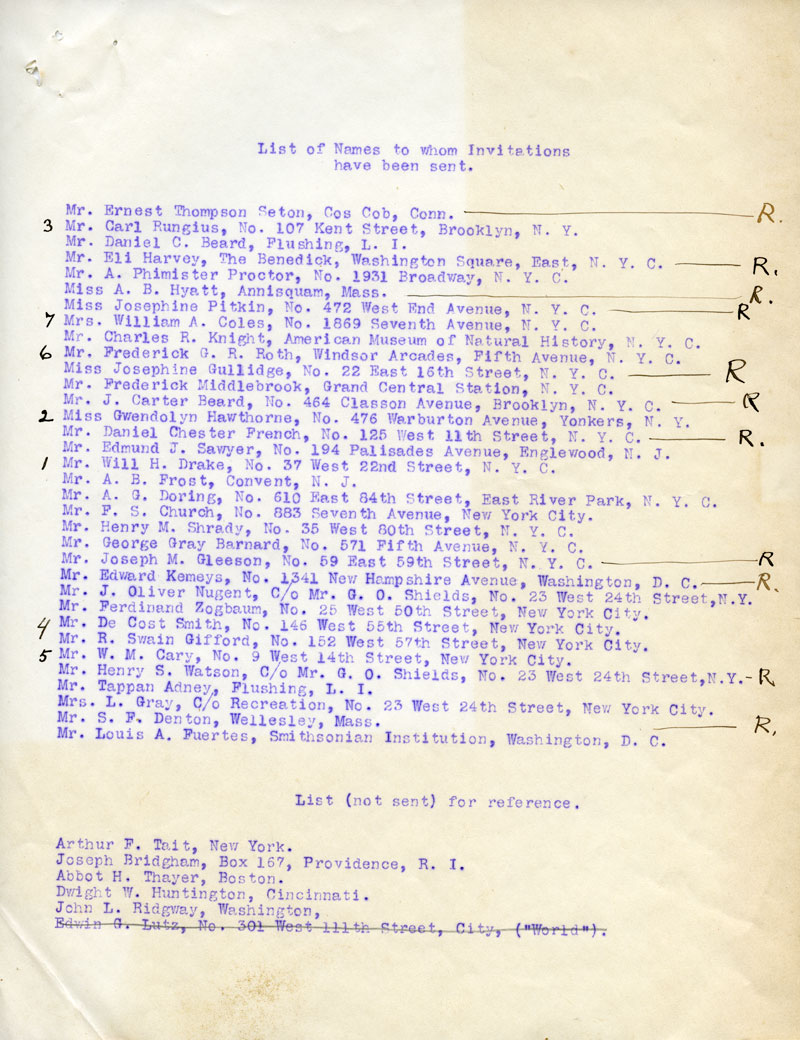

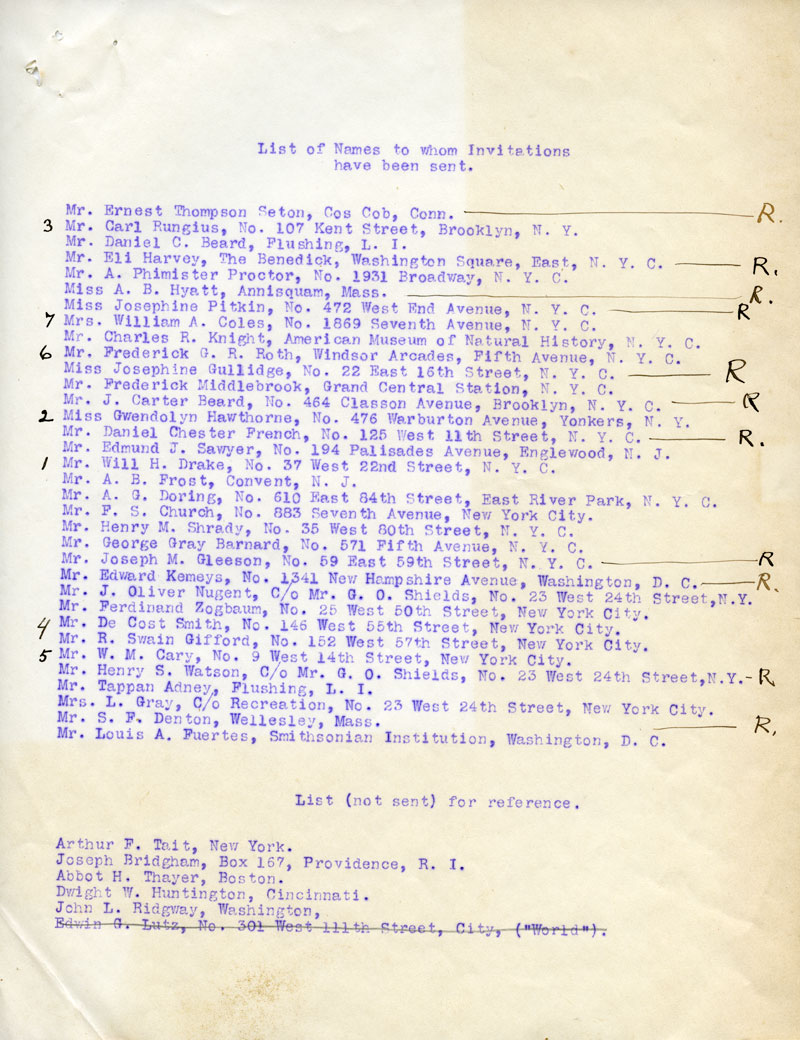

It was to meet these needs that the Society constructed the artists’ studio in the Lion House. Located in the northeast corner of the building, the studio included two spaces: one room for lockers and supplies; and a second room, approximately 21 by 26 feet, containing a workspace and a large wire-fronted enclosure into which animals were transferred by means of a shift cage, which ran on tracks underneath the flooring of the Lion House. William T. Hornaday, the Bronx Zoo’s first director, took great care in the studio’s design, and he convened a group of artists—composed of Daniel C. Beard, Eli Harvey, A. P. Proctor, and Carl Rungius—to offer recommendations.

These artists were also among the select group invited to the opening of the studio. Although a few, including Hyatt, sent their regrets for the debut celebration, the studio soon became “eagerly utilized” according to then-Vice President of NYZS Henry Fairfield Osborn. The Society’s Annual Report for 1903 confirmed that a “large number of animal painters and sculptors have taken advantage of the facilities afforded to them” in the Zoo at large and especially in the studio. In addition to Hyatt and to those who counseled Hornaday on the studio’s design, other prominent animal artists known to have worked in the Zoo in its early years were George Grey Barnard, Gutzon Borglum, Paul Bransom, Charles Livingston Bull, Avard Fairbanks, Paul Herzel, Charles R. Knight, Frederick G. R. Roth, Eugenie Shonnard, and Katharine Lane Weems.

In the end, however, the studio was not the success the Society hoped it would be. Although several artists worked there, the studio’s limited lighting and the promise of fresh air and greater variety of animal life drew artists back out into the Zoo at large. By 1912, Fairbanks—whom Hyatt was said to have mentored during the time they shared at the Zoo—noted that the studio was really only used during inclement weather.

Beyond the studio, officials still sought to oblige artists working at the Zoo. Hornaday arranged a special reduced rate for artists at the nearby Parkway Hotel. “The place seems respectable,” he assured visiting artists, “although of course there is a bar-room attachment”—a feature that likely bothered the teetotaling Hornaday more than his artist guests. Hornaday also sent out a general order to all employees that “artists, sculptors, zoologists and students generally” were to be given special attention and “whenever possible, seats should be offered.” Some artists also devised ways to avoid the crowds of visitors. Bransom, for instance, recalled retreating to Zoo buildings that “were noted not only for their beautiful inhabitants but for their unique odors.” Not only would most visitors rush through such buildings, but Bransom also would be given plenty of space on his subway ride home.

Further still, in addition to encouraging artists working at the Zoo, NYZS also sought to support wildlife art by hiring sculptors to decorate the Zoo’s original buildings, and visitors today can see the work of Eli Harvey, Charles R. Knight, and A. P. Proctor adorning such landmark-status buildings as the Monkey House, the Lion House, the Bird House (now an administration building), and the Elephant House (now Zoo Center). Over time, in addition to Anna Hyatt Huntington’s Reaching Jaguars, the Zoo’s outdoor sculpture collection expanded to include other works such as casts of Weems’s Indian rhinoceroses, Bessie and Victoria, modeled after an animal at the Bronx Zoo. The Society also collected wildlife paintings and displayed this collection and visiting works in the Zoo’s administration building and later in its Heads and Horns Gallery. Within the Society’s collection were works by Rosa Bonheur, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Robert Bruce Horsfall, Knight, Rungius, and other important wildlife artists.

Why, one might wonder, did the Zoo go to such lengths—including devoting significant funds—to oblige and to encourage the work of animal artists? The answer actually lies in the founding mandates of the New York Zoological Society:

First. — The establishment of a free zoological park containing collections of North American and exotic animals, for the benefit and enjoyment of the general public, the zoologist, the sportsman and every lover of nature.

Second. — The systematic encouragement of interest in animal life, or zoology, amongst all classes of the people, and the promotion of zoological science in general.

Third. — Co-operation with other organizations in the preservation of the native animals of North America, and encouragement of the growing sentiment against their wanton destruction.

For the Society’s founders, who promoted the scientific study of animals, wildlife painting and sculpture served as important tools to zoologists at a time when photographic technology lacked the ability to capture significant details—color foremost among them. Yet beyond a scientific audience, the Society saw wildlife art as a vital means not only of educating the public but also of stimulating interest in animals. As an 1897 Zoological Society Bulletin saw it, “the more the artistic reproduction of wild animals in painting and sculpture is increased, the more interest will the public take in our fauna, and the more will knowledge of it be increased.”

This increased knowledge, the Society believed (and continues to believe today), would in turn facilitate its third mandate, the preservation of wildlife. But NYZS also saw animal art as another means of “preserving” wildlife: fearing a losing battle against the fates that nearly caused the extinction of such animals as the American bison at the end of the nineteenth century, the Society viewed wildlife art as a tool to document the animals they worried would soon disappear. Advocating the Society’s role in supporting wildlife art, its first annual report lamented that “although our magnificent series of large game animals is rapidly passing away, the walls of nearly if not quite all the great art galleries in America are absolutely destitute of representations of them, much less of such representations as their size, beauty and importance richly deserve!” A catalogue of the Society’s painting collection published more than thirty years later echoed the importance of preserving through art “some of our fast disappearing creatures.”

Thankfully, the situation for some creatures has become less dire since the Society first turned to art as a means of preservation. This in part has come through organized conservation efforts, such as the Society’s involvement in repopulating the American bison in the West during the early twentieth century. Today, the Wildlife Conservation Society continues to strive to protect wildlife and wild places—to make sure, in other words, that the wildlife art created at the Zoo or collected by the Society does not become a memorial to lost species but rather serves as a celebration of living, thriving animals.

New York Zoological Park postcard, circa 1906, showing the Lion House from the northeast. Wildlife Conservation Society Archives.

×

Lion inside shift cage in the Bronx Zoo artists’ studio, 1903. Wildlife Conservation Society Archives.

×

List of those invited to the opening of the artists’ studio in the Lion House, 1903. Wildlife Conservation Society Archives.

×

A. P. Proctor sculpting a baboon at the Bronx Zoo, probably 1901. Wildlife Conservation Society Archives.

×

South side of Zoo Center, formerly known as the Elephant House. The sculpture on the building’s south side is by A. P. Proctor, and the building is flanked by casts of Katharine Lane Weems’s Indian rhinoceroses, Bessie and Victoria. Photo by Julie Larsen Marher © Wildlife Conservation Society.

×

New York Zoological Society art gallery, located in the Bronx Zoo’s Administration Building, circa 1920. Wildlife Conservation Society Archives.

×

Title page from the Second Annual Report of the NYZS, featuring the Society’s seal, designed by Charles R. Knight.

×

Cast of the Hand of Anna Hyatt Huntington, 1935, Aluminum. Lent by the Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY.

Cast of the Hand of Anna Hyatt Huntington, 1935, Aluminum. Lent by the Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY. Door Panel: Death of a Knight, 1924-29, Bronze. Lent by the Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY.

Door Panel: Death of a Knight, 1924-29, Bronze. Lent by the Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY. Bulls Fighting, 1905, Bronze. Lent by the Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY.

Bulls Fighting, 1905, Bronze. Lent by the Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY.