Bradley Park Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies St. Mary’s College of Maryland |

This unit provides a general introduction to three aesthetic concepts—mono no aware, wabi-sabi, and yūgen — that are basic to the Japanese arts and “ways” (dō).(1) Secondly, it traces some of the Buddhist (and Shintō)(2) influences on the development of the Japanese aesthetic sensibility.

In addition to introducing students to the concepts of mono no aware, wabi-sabi, and yūgen, the unit provides students with an opportunity to study the appearance of these concepts in Japanese art and life through an examination of images and texts. Furthermore, students are introduced to the relationship between these concepts and Buddhism, and hence the larger significance of these ideas.

Each aesthetic idea is introduced with a paradigmatic example in order to offer a tangible image to connect with the general features defining each aesthetic category. The “Aesthetic Characteristics” section provides a basic description of the defining qualities associated with each aesthetic concept and how the concept has been used across various artistic disciplines. The “Philosophical Significance” section explores the relationship between the defining features belonging to a particular aesthetic idea and the Buddhist (as well as Shintō) ideas contributing to its significance.

The unit is designed to be employed in a variety of ways and across a wide range of contexts. It can be incorporated into a wide range of classes including but not limited to Asian art, Asian literature, Asian or comparative philosophy, or Buddhism. Each aesthetic concept can be treated as a stand-alone module (approximately one classroom hour) or the entire unit can be used across several classes (approximately three classroom hours).

Moreover, the unit can be successfully integrated with additional units to create a larger course of study on Buddhism, Buddhist Aesthetics, Buddhist Literature, etc. See also:

- Buddhism in the Classic Chinese Novel Journey to the West

- Buddhist Art in East Asia: Three Introductory Lessons Towards Visual Literacy

- Dialogue and Transformation: Buddhism in Asian Philosophy

- Foundations and Transformations of Buddhism: An Overview

- Japanese Aesthetics and The Tale of Genji

- Ox-herding: Stages of Zen Practice

Classic Example: Cherry Blossoms

From: The Plum Village Photo Album

Mono no Aware : Readings

*** Most important

* Recommended

* Optional

*** “Chapter Six: ŌNISHI Yoshinori and the Category of the Aesthetic,” pp. 115-140 in Michael MARRA. (Ed.). Modern Japanese Aesthetics: A Reader. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999.

** “Japanese Aesthetics,” Donald KEENE, pp. 27-41 and “The Vocabulary of Japanese Aesthetics, I, II, III,” WM. Theodore De BARY, editor, pp. 43-76, in Nancy G. HUME (Ed.). Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader. Albany: SUNY Press, 1995.

** “MOTOORI Norinaga’s Hermeneutic of Mono no Aware: The Link Between Ideal and Tradition,” pp. 60-75 in Michael MARRA. (Ed.). Japanese Hermeneutics: Current Debates on Aesthetics and Interpretations. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002.

* “The Central Problematic: Detachment vs. Sympathy,” pp 256-260, in Steve ODIN. Artistic Detachment in Japan and the West. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2001.

* RAILEY, Jennifer McMahon. “Dependent Origination and the Dual-Nature of the Japanese Aesthetic,” Asian Philosophy. Vol. 7, No. 2 (July, 1997), 123-133.

Mono no Aware : Discussion Questions

- What is Jiyen the Monk trying to express in the following poem?

Let us not blame the wind, indiscriminately,

That scatters the flowers so ruthlessly;

I think it is their own desire to pass away before their time has come .

Jiyen the Monk (1155-1225)

(In D.T. SUZUKI, Zen and Japanese Culture . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973, p. 390.)

- Besides cherry blossoms, what other examples are there of aesthetic objects whose impermanence is an integral part of their beauty?

- What is the relationship between time and beauty in Western art?

- How does the Western dramatic or literary genre of “tragedy” resemble or differ from the Japanese focus on mono no aware?

Mono no Aware : Aesthetic Characteristics

The aesthetic category of mono no aware ( 物の哀れ ), or the “poignant beauty of things,” describes a cultivated sensitivity to the unavoidable transience of the world. Due to their vivid fragility, cherry blossoms, which are easily scattered by the slightest wind or rain, have become the archetypal symbol of the melancholic beauty of impermanence — the transitory presence of the cherry blossom intensifies the experience by underscoring the blossoms’ delicate beauty. Mono no aware foregrounds finite existence within the flow of experience and change.

Since mono no aware developed as an everyday expression of pathos, it resides at the center of the Japanese premodern aesthetic sensibility and thereby has become something of a broad aesthetic category. However, since the interpretation of MOTOORI Norinaga (1730-1801) mono no aware has been most notably associated with literary texts like Heian (794-1185) court poetry (waka — Chinese-style poetry in Japan ) and The Tale of Genji by MURASAKI Shikibu (ca. 1010).

Mono no Aware : Philosophical Significance

The notion of mono no aware originates in the indigenous Shintō ( 神道 ) sensibility, which was highly sensitive to the awe-inspiring dimensions of the natural world. As a religious sensibility, mono no aware is related to two other notions, namely, “the vitality of things” (mono no ke 物の気 ) and “the mood of things” (mono no kokoro 物の心 ).

- The vitality of things concerns the vital energy (ke) exuded by real world things (mono). For example, the gates or archways (torii 鳥居 ) of shrines and temples originally were meant to have a vital energy and therefore served as a sacred place with cosmic charisma. (See http://www.exeas.org/resources/photos/shrinegates.jpg for an image of shrine gates.)

In terms of religious practice, Shintō aims at the cultivation of heightened openness. In other words, one strives to capture “the mood of things” (mono no kokoro) or feel the tangible world, thereby realizing a profound sympathetic resonance with one’s environment. To be affectively and cognitively attuned to the things around us is the most intimate form of knowledge — that is, to know the heart-mind (kokoro) of a thing (mono).

- Thus, mono no ke and mono no kokoro provide the background against which mono no aware emerges as an aesthetic notion. Mono no aware, then, represents a refined sensibility indicating a sincere heart capable of resonating with the vital energy of things in a constantly changing world.

With the introduction of Buddhism into Japan, the awareness of the world as a process became explicitly conceived as “impermanence” (mujō 無常 — literally, “without constancy”). The traditional Buddhist attention to the problem of “angst” or “suffering” (Sanskrit dukkha) in the face of the impermanence of things became aestheticized in Japan. Mono no aware is not only a living realization of impermanence, but also an aesthetic orientation towards the deep beauty inherent in the transitory nature of existence.

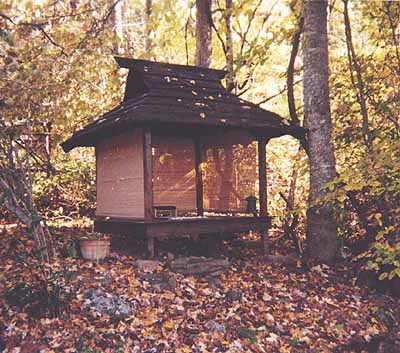

Classic Example: Tea Hut

From: Mountain Light Sanctuary

The snow-covered mountain path

Winding through the rocks

Has come to its end;

Here stands a hut,

The master is all alone;

No visitors he has,

Nor are any expected.

Sen no Rikyū (1521-1591)

(D.T. SUZUKI, Zen and Japanese Culture, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959, p. 282)

Wabi-Sabi : Readings

*** Most important

** Recommended

*** SAITO, Yuriko. “The Japanese Aesthetics of Imperfection and Insufficiency,” The Journal Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Vol. 55, No. 4 (Autumn, 1997), 377-385.

** HAGA, Kōshirō, “The Wabi Aesthetic through the Ages,” and Sen Sōshitsu XV, “Reflections on Chanoyu and its History,” in Tea in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1989.

** “Japanese Aesthetics,” Donald KEENE, pp. 27-41 and “The Vocabulary of Japanese Aesthetics, I, II, III,” WM. Theodore De BARY (Ed.). pp. 43-76, in Nancy G. HUME (Ed.). Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader. Albany: SUNY Press, 1995.

* RAILEY, Jennifer McMahon. “Dependent Origination and the Dual-Nature of the Japanese Aesthetic,” Asian Philosophy. Vol. 7, No. 2 (July, 1997), 123-133.

Wabi-Sabi : Discussion Questions

- What examples of wabi or sabi can be found in your own culture, community, or home?

- How do objects in our world reveal time?

- Are all antiques examples of wabi and sabi? If not, why not?

- What is nostalgia? How is it similar to, or different from, wabi and sabi?

Wabi-Sabi : Aesthetic Characteristics

While the aesthetic categories of wabi ( 詫び ), “rustic beauty,” and sabi ( 寂び ), “desolate beauty,” can be treated separately, they are ultimately complimentary concepts that support a coherent aesthetic sense. The qualities usually associated with wabi and sabi are: (1) austerity, (2) imperfection, and (3) a palpable sense of the passage of time.

The “way of tea” (chadō; also called cha no yu) is closely associated with the wabi-sabi aesthetic. For example, the famous tea master Sen no Rikyū (1521-1591) captures the aesthetic of simplicity at the very heart of the tea ceremony: “the art of cha-no-yu consists in nothing else but in boiling water, making tea, and sipping it” (cited in D.T. SUZUKI , Zen and Japanese Culture . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973, p. 280.) Sen no Rikyū’s phrase “consists in nothing else” is meant to indicate the discipline of cha-no-yu as a way of spiritual and moral cultivation. In other words, one’s entire being is absolutely and utterly occupied with the seemingly mundane act of tea.

In many ways, this spiritual discipline of tea can be understood in the context of the Zen master Rinzai’s (? – 866) teachings(3): “The Buddha-dharma does not have a special place to apply effort; it is only the ordinary and everyday — relieving oneself, donning clothes, eating rice, lying down when tired,” as well as Zen master Dōgen’s (1200-1253)(4) meditative focus on shikantaza ( 只管打座 ) or “just sitting.”

See also:

“Japanese Aesthetics, Wabi-Sabi, and the Tea Ceremony” from

http://www.art.unt.edu/ntieva/artcurr/asian/wabisabi.html

“What is Wabi-Sabi?”

http://www.nobleharbor.com/tea/chado/WhatIsWabi-Sabi.htm

The Japanese Tea Ceremony

http://brian.hoffert.faculty.noctrl.edu/TEACHING/TeaCeremony.html

Wabi-sabi : Philosophical Significance

Like mono no aware, wabi and sabi are embedded in a deep sense of mortality. Both concepts invoke a contemplative mood of loneliness, a plaintive attentiveness to the passage of time, and sensitivity to the human being’s place within the natural world. To put it somewhat differently, it is against the holistic background of nature, as an endless process of creation and destruction, formation and decay, life and death that the individual human being stands out in her solitariness and uniqueness. It is in this state of solitariness that one is brought back to one’s authentic self and back to confront the fuller existential(5) and religious dimensions of human experience.

Moreover, it is philosophically significant that nature represents the fundamental background of human existence, which is to say that these traditional Japanese categories reject any form of the culture vs. nature dichotomy.(6) Indeed, the aesthetics of wabi and sabi insist that our most refined cultural practices need to express the essential relationship between human beings and the natural world. The aestheticization of nature is the human, i.e., cultural, contribution to nature rather than something distinct from nature. Due to the centrality of nature in Japanese aesthetics, “imperfection” became valued as a fundamental quality of beauty. The writings of the Buddhist monk YOSHIDA Kenkō (1283-1350) represent one of the classical statements concerning the Japanese aesthetics of imperfection:

It is only after the silk wrapper has frayed at the top and bottom, and the mother-of-pearl has fallen from the roller that a scroll looks beautiful. I was impressed to hear the Abbot Kōyū say, “It is typical of the unintelligent man to insist on assembling complete sets of everythings. Imperfect sets are better.” In everything, no matter what it may be, uniformity and completeness are undesirable.

(YOSHIDA, Kenkō, Essays in Idleness: The Tsurezuregusa of Kenkō. Tr. Donald KEENE. New York: Columbia University Press, 1967, 115, as quoted. in Yuriko SAITO, “The Japanese Aesthetics of Imperfection and Insufficiency” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 55:4, Fall 1997, 377-385.)

While Shintō forms the cultural basis for the Japanese love of nature, the resolute confrontation with the impermanence of Buddhism represents a philosophical commitment to facing things as they are, rather than how they ought to be. It is important to note, however, that this is not a form of resignation in the face of imperfection, but an embracing affirmation of the inherent imperfection of all things. Thus, the aesthetics of wabi-sabi exemplify the intertwining of a religio-philosophical viewpoint and the aesthetics that are intended to bring it to its fullest expression.

Principal Example: Mountains and Clouds

From: Jimages Photography

Gaze out far enough,

Beyond all cherry blossoms

and scarlet maples,

to those huts by the harbor

fading in the autumn dusk.

FUJIWARA Teika (1162-1241)

(William LAFLEUR, The Karma of Words: Buddhism and the Literary Arts in Medieval Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983, p. 97.)

Yūgen : Readings

*** Most important

** Recommended

* Optional

*** “Symbol and Yūgen: Shunzei’s Use of Tendai Buddhism” (pp 80-107) in William LAFLEUR, The Karma of Words: Buddhism and the Literary Arts in Medieval Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983

** “An Invitation to Contemplation: The Rock Garden of Ryōanji and the Concept of Yūgen” (pp 24-37) in Eliot DEUTSCH, Studies in Comparative Aesthetics. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1975.

** “Classical Japanese Aesthetics” (pp. 103-117) and “Yūgen: The Ideal of Beauty” (pp 246-249) in Steve ODIN, Artistic Detachment in Japan and the West. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2001.

** Sen’ichi HISAMATSU. The Vocabulary of Japanese Literary Aesthetics. Tokyo: Bunkyo-ku, 1963.

** TOSHIKO Izutsu and Toyo. The Theory of Beauty in the Classical Aesthetics of Japan. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff, 1981.

** “Zeami on the Art of Nō Drama: Imitation, Yūgen, and Sublimity” (pp 177-191) by Makoto UEDA in Nancy G. HUME (Ed.). Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader. Albany: SUNY Press, 1995.

* ANDRIJAUSKAS, Antanas. “Specific Features of Traditional Japanese Medieval Aesthetics,” Dialogue and Universalism. No1-2/2003, 199-220.

* Steve ODIN. “The Penumbral Shadow: A Whiteheadian Perspective on the Yūgen Style of Art and Literature in Japanese Aesthetics.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies (12/1), March 1985.

Yūgen : Discussion Questions

- Is “mystery” important to art? If so, why?

- What is “depth” in art? Philosophy? Life?

- Why is it important aesthetically, philosophically, and ethically that the “big picture” not completely overwhelm or de-value the particular?

- Describe the aesthetic “tension” experienced in the example images or poem provided? How does this tension make you feel?

Yūgen : Aesthetic Characteristics

The two characters that comprise the word yūgen ( 幽玄 ) refer to that which resists being clearly discerned. More specifically, the first character, yū ( 幽 ) refers to “shadowy-ness” and “dimness,” while the second character gen ( 玄 ) refers to “darkness” and “blackness.”

ŌNISHI Yoshinori argues that the concept of yūgen appears in four different kinds of literature: (1) Zen and Chinese Daoist writings, (2) Chinese poetry, (3) Waka (Chinese-style poetry in Japan), and (4) treatises on poetry and Nō plays (Ōnishi 9). In the case of Daoist and Zen literature, the concept takes on a broad “metaphysical”(7) coloring, while the poetic conception of yūgen is a more straightforwardly descriptive. And then, in the critical treatises on Waka and Nō, yūgen begins to be used in more “theoretical” manner in order to justify aesthetic judgments and as a normative concept(8) for reflecting upon and evaluating aesthetic works.

Aside from its literary currency, yūgen also became closely associated with sumi-e inkwash painting. (See http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/singleObject.cfm?ObjectId=11842 and http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/highlight_search?acc=1954.4&page=1&CollectionID=6&Keyword=ink for examples of sumi-e.) The visual and literary images typically used to convey the quality of yūgen consisted of things like huts being encroached upon by dusk, the enveloping of mountains by mist, the obscuring of the moon by clouds, the fading of people into the shadows, etc. Other perceptible qualities closely associated with these images include colorlessness, vagueness, stark simplicity, silence, and stillness, while the felt qualities include elegance, subtlety, grace, loneliness, tranquility, and a deep sense of pathos.

Yūgen : Philosophical Significance

Tendai Buddhism exercised a profound influence on the concept of yūgen.(9) This influence can be analyzed into two basic strands. The first strand concerns the Tendai practice of shikan ( 止観 “tranquility-contemplation”) meditation, while the second strand returns to the basic Buddhist focus on mujō ( 無常 “impermanence”).

The Tendai practice of shikan meditation becomes the lens through which the yūgen quality of things comes to be apprehended, according to William LAFLEUR in The Karma of Words: Buddhism and the Literary Arts in Medieval Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983) . In the end, shikan meditation, practiced for the realization of three truths (the phenomenal ( 假 ke ), the void ( 空 kū ), and the middle ( 中 chū )), forms the attitudinal posture through which yūgen is actualized. LaFleur argues that the Tendai truths emphasizing interdependency of all things functioned as an affirmation of the “indeterminacy of meaning.” As such, this insight produced a dramatic increase in the depth of meaning and meanings (fukasa 深さ ) to be written and found in the arts.

Books

DEUTSCH, Eliot. Studies in Comparative Aesthetics. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1975.

HEINE, Steven. A Blade of Grass. Japanese Poetry and Aesthetics in Dōgen Zen. New York: Peter Lang Pub, 1997.

HUME, Nancy G. (Ed.). Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader. Albany: SUNY Press, 1995.

LAFLEUR, William. The Karma of Words: Buddhism and the Literary Arts in Medieval Japan.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983

MARRA, Michael (Ed.). Japanese Hermeneutics: Current Debates on Aesthetics and Interpretations. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002.

MARRA, Michael. (Ed.). Modern Japanese Aesthetics: A Reader. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999.

ODIN, Steve. Artistic Detachment in Japan and the West. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2001

SEN’ICHI, Hisamatsu. The Vocabulary of Japanese Literary Aesthetics. Tokyo: Bunkyo-ku, 1963.

SUZUKI, Daisetz Tetsuro. Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973.

TOSHIHIKO, Izutsu and Toyo. The Theory of Beauty in the Classical Aesthetics of Japan. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff, 1981.

Journal Articles

ANDRIJAUSKAS, Antanas. “Specific Features of Traditional Japanese Medieval Aesthetics,” Dialogue and Universalism. No1-2/2003, 199-220.

MARRA, Michael. “Japanese Aesthetics: The Construction of Meaning,” Philosophy East and West. Vol. 45, No. 3 (July, 1995), 367-387. http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-PHIL/miche2.htm

RAILEY, Jennifer McMahon. “Dependent Origination and the Dual-Nature of the Japanese Aesthetic,” Asian Philosophy. Vol. 7, No. 2 (July, 1997), 123-133.

SAITO, Yuriko. “The Japanese Aesthetics of Imperfection and Insufficiency,” The Journal Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Vol. 55, No. 4 (Autumn, 1997), 377-385.

Web Resources

“Teaching Japanese Aesthetics: Whys and Hows for Non-Specialists” by Mara MILLER http://www.aesthetics-online.org/ideas/miller.html

“Japanese Aesthetics, Wabi-Sabi, and the Tea Ceremony,” North Texas Institute for Educators on the Visual Arts

http://www.art.unt.edu/ntieva/artcurr/asian/wabisabi.html

“What is Wabi-Sabi?”

http://www.nobleharbor.com/tea/chado/WhatIsWabi-Sabi.htm

The Japanese Tea Ceremony

http://brian.hoffert.faculty.noctrl.edu/TEACHING/TeaCeremony.html