SHINDEN ROOTS

The main predecessor of the shoin style is the shinden, a

mode of building favored by the upper class in the Heian period (794-1185),

the classical period of Japanís cultural history when native styles of

expression in calligraphy, poetry, and painting were also developed and

the warrior class rose. The essential elements of the basic shinden

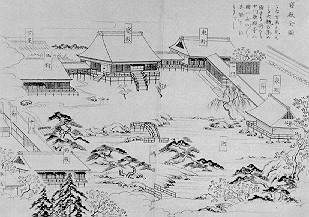

plan is best understood by early representations found in narrative picture

scrolls (emakimono) and descriptions in old diaries. A particularly

notable account of the ideal shinden residence can be found in the Kaoku

zakko, a treatise on architecture by Sawada Natari (1775-1845).

The main predecessor of the shoin style is the shinden, a

mode of building favored by the upper class in the Heian period (794-1185),

the classical period of Japanís cultural history when native styles of

expression in calligraphy, poetry, and painting were also developed and

the warrior class rose. The essential elements of the basic shinden

plan is best understood by early representations found in narrative picture

scrolls (emakimono) and descriptions in old diaries. A particularly

notable account of the ideal shinden residence can be found in the Kaoku

zakko, a treatise on architecture by Sawada Natari (1775-1845).  In

this illustration (seen at top) the central hall is flanked to the east

and west by outlying structures called tai-no-ya. Roofed corridors

known as ro connected the one story buildings which were raised about a

foot above ground. Two small pavilionlike structures are also included,

the one to the east izumo-dono ("fountain pavilion") and that to the west

the tsuri-dono ("fishing pavilion"). Since the ro passageways leading

to the gazebos are halved by chumon ("middle gates") they are also called

chumon-ro. The complex faces south and the courtyard includes a pond

and formal garden. Chinese influence on the formation of Japanese

concepts is evident in the symmetry, southern orientation, and building-garden

relationship. Interiors were sparsely furnished and easily rearranged

making privacy virtually unobtainable. It contained partitions, sliding

doors, and shutters that could be readily removed to make smaller rooms

into larger ones and to open the whole interior of a building to the out-of-doors.

The rooms of the shinden mansions had bare wooden floors, with portable

straw mats laid out individually where needed, and most had no built-in

fixtures. In the early stages of shinden design, the roomy main hall

was used for many different puposes. As time progressed, however, informality

and privacy and more differentiation from areas of public and formal use

were desired. Asymmetry developed in response to changes in function

and structure of the interior space. The central space (moya) under

the main roof of the shinden hall came to be used mainly for ceremonial

functions, with the secondary spaces (hisashi) surrounding the moya used

for daily living. Gradually, the division between public and

private spaces became more distinct necessitated more definite interior

partitioning. These new architectural elements were related to changes

in patterns of daily living appearing with the rise of the new warrior

class.

In

this illustration (seen at top) the central hall is flanked to the east

and west by outlying structures called tai-no-ya. Roofed corridors

known as ro connected the one story buildings which were raised about a

foot above ground. Two small pavilionlike structures are also included,

the one to the east izumo-dono ("fountain pavilion") and that to the west

the tsuri-dono ("fishing pavilion"). Since the ro passageways leading

to the gazebos are halved by chumon ("middle gates") they are also called

chumon-ro. The complex faces south and the courtyard includes a pond

and formal garden. Chinese influence on the formation of Japanese

concepts is evident in the symmetry, southern orientation, and building-garden

relationship. Interiors were sparsely furnished and easily rearranged

making privacy virtually unobtainable. It contained partitions, sliding

doors, and shutters that could be readily removed to make smaller rooms

into larger ones and to open the whole interior of a building to the out-of-doors.

The rooms of the shinden mansions had bare wooden floors, with portable

straw mats laid out individually where needed, and most had no built-in

fixtures. In the early stages of shinden design, the roomy main hall

was used for many different puposes. As time progressed, however, informality

and privacy and more differentiation from areas of public and formal use

were desired. Asymmetry developed in response to changes in function

and structure of the interior space. The central space (moya) under

the main roof of the shinden hall came to be used mainly for ceremonial

functions, with the secondary spaces (hisashi) surrounding the moya used

for daily living. Gradually, the division between public and

private spaces became more distinct necessitated more definite interior

partitioning. These new architectural elements were related to changes

in patterns of daily living appearing with the rise of the new warrior

class.

[Main Page]

[Development]

[Functions]

[Features]

In

this illustration (seen at top) the central hall is flanked to the east

and west by outlying structures called tai-no-ya. Roofed corridors

known as ro connected the one story buildings which were raised about a

foot above ground. Two small pavilionlike structures are also included,

the one to the east izumo-dono ("fountain pavilion") and that to the west

the tsuri-dono ("fishing pavilion"). Since the ro passageways leading

to the gazebos are halved by chumon ("middle gates") they are also called

chumon-ro. The complex faces south and the courtyard includes a pond

and formal garden. Chinese influence on the formation of Japanese

concepts is evident in the symmetry, southern orientation, and building-garden

relationship. Interiors were sparsely furnished and easily rearranged

making privacy virtually unobtainable. It contained partitions, sliding

doors, and shutters that could be readily removed to make smaller rooms

into larger ones and to open the whole interior of a building to the out-of-doors.

The rooms of the shinden mansions had bare wooden floors, with portable

straw mats laid out individually where needed, and most had no built-in

fixtures. In the early stages of shinden design, the roomy main hall

was used for many different puposes. As time progressed, however, informality

and privacy and more differentiation from areas of public and formal use

were desired. Asymmetry developed in response to changes in function

and structure of the interior space. The central space (moya) under

the main roof of the shinden hall came to be used mainly for ceremonial

functions, with the secondary spaces (hisashi) surrounding the moya used

for daily living. Gradually, the division between public and

private spaces became more distinct necessitated more definite interior

partitioning. These new architectural elements were related to changes

in patterns of daily living appearing with the rise of the new warrior

class.

In

this illustration (seen at top) the central hall is flanked to the east

and west by outlying structures called tai-no-ya. Roofed corridors

known as ro connected the one story buildings which were raised about a

foot above ground. Two small pavilionlike structures are also included,

the one to the east izumo-dono ("fountain pavilion") and that to the west

the tsuri-dono ("fishing pavilion"). Since the ro passageways leading

to the gazebos are halved by chumon ("middle gates") they are also called

chumon-ro. The complex faces south and the courtyard includes a pond

and formal garden. Chinese influence on the formation of Japanese

concepts is evident in the symmetry, southern orientation, and building-garden

relationship. Interiors were sparsely furnished and easily rearranged

making privacy virtually unobtainable. It contained partitions, sliding

doors, and shutters that could be readily removed to make smaller rooms

into larger ones and to open the whole interior of a building to the out-of-doors.

The rooms of the shinden mansions had bare wooden floors, with portable

straw mats laid out individually where needed, and most had no built-in

fixtures. In the early stages of shinden design, the roomy main hall

was used for many different puposes. As time progressed, however, informality

and privacy and more differentiation from areas of public and formal use

were desired. Asymmetry developed in response to changes in function

and structure of the interior space. The central space (moya) under

the main roof of the shinden hall came to be used mainly for ceremonial

functions, with the secondary spaces (hisashi) surrounding the moya used

for daily living. Gradually, the division between public and

private spaces became more distinct necessitated more definite interior

partitioning. These new architectural elements were related to changes

in patterns of daily living appearing with the rise of the new warrior

class.