Icons: Art or Religious Artifact?

Dressed in a black cassock, the Reverend Boris Mikhailov appeared out of a shadowy corner of Moscow's St. John the Baptist Russian Orthodox Church. Wading through a smoky trail of incense, he walked past the congregation of mostly kerchiefed women who were attending a Lenten service at the side chapel. He paused just before the altar and scanned the clutter of gilded icons that hung on the walls of the 18th Century church. "The Christ in the iconostasis, 17th Century," he began, excitedly pointing to some of the church's more venerated icons. "Holy Mary with child Christ, end of the 17th Century. Holy Mary with whole family, a copy of Raphael's." An art historian by training, Mikhailov became a priest in 1991, at the age of 50. His spiritual journey parallels the expansion of religious freedoms initiated during Gorbachev's perestroika that began in the mid-1980s. And in many ways he personifies the debate that remains one of the last vestiges of communism in the relationship between church and state. The debate, in which Mikhailov is a leading voice, involves a confrontation between the church and the state over the ownership and stewardship of churches and icons. And it illustrates Russia's struggle to reconcile the 70-year history of communist reign with the country's thousand-year-old tradition of Russian Orthodoxy. Clasping the crucifix that fell from under his long graying beard and rested on top of his protruding belly, Mikhailov said that the first phase of restoring the role of the church in Russian society was the reopening of churches. But the property is still owned and controlled by the government. "We just use the property, we don't own it and we don't pay rent," he said. "But now we are beginning another period, a second period. The process of getting the property back." Central to the confrontation is the fate of some of the icons during the era of communist rule. Many were destroyed, but some of the oldest and most venerated were seized and wound up in museums where they still reside much to the indignation of the church. Mikhailov himself has walked on both sides of the issue. During communist rule, he studied and lectured on the historical value of icons to Russian culture. But since joining the clergy, he now views icons for their implicit spiritual value and their liturgical purpose. After the 1917 Russian Revolution, Mikhailov explained, all the property of the church was confiscated by the state. The practice of religion was restricted; churches were closed, destroyed or in many cases turned into factories or apartment buildings. Before the Revolution, there were over 500 churches in Moscow. In 1989 there were only 47 open. St. John the Baptist was one of them and the collection of icons that give the church it's ominous garage sale look were taken for protection from surrounding churches that were shutdown. Today, there are about 430 churches operating in Moscow, Mikhailov said. But all of those churches are still owned by the state and the government must approve any restoration work, including the return of icons to the churches from where they were confiscated. "There is a problem. The state will not agree to return all the property," Mikhailov said. "It's an ideological difference. They say Śthe icons belong to the culture. They're national treasures and belong to mankind.' But for the church, this is about the most worshipped of icons." One of the most revered icons in all of Russia, Our Lady of Vladimir, came to symbolize the church's struggle and has recently found a not so happy comprise. The 12th-century Byzantine icon was confiscated after the Bolshevik revolution from the Dormition Cathedral in the Kremlin and placed in the State Tretykov Gallery. Since the end of the communism, the church has fought to have the icon returned where parishioners could properly venerate it. But the gallery argued that the icon would be destroyed if put to liturgical use. In September 1999, after years of negotiations, the icon was given to the Church of St. Nicholas, also referred to as the "Church Museum," which is located on the gallery's premises. Placed in a special climate-controlled case, with temperature gauges located in every corner, and track lighting illuminating the painting of the mother and child, the church takes on the sterile look of a museum. Unlit candles rest in polished holders. The smell of incense is noticeably absent. A curator at the Tretykov Gallery, who did not want to be identified, explained that museums are the most appropriate place for "masterpiece" icons. In museums, they can be seen by the masses regardless of their religious affiliation. Whereas in churches, there would be more restrictions. There is also the issue of security, she explained: In museums, icons are well-protected and cared for, something that churches cannot assure. Shuttering at the notion of icons as masterpieces, Mikhailov insists that the value of icons as a holy asset is greater than the commodity value that collectors often ascribe to them. "It's the believing that gives the art a soul," he said. Complicating the debate is the fact that the time element that elevates icons to masterpiece status in the eyes of museums and collectors also raises their holy value. It is the investment of veneration over a period of time that apparently gives one icon a greater spiritual worth than another. "A picture is just a picture," explained Richard Schneider, a visiting professor of Iconology at St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary. "It's an icon when people regard it as an icon, treat it and venerate it as such. And to do that it has to be surrounded by holiness." "Icons are made to die, just like us," he added. "They fade away, they get kissed up. They get smoked up. Or they get painted overŠI would like to see icons in churches and the really old ones not be handled so much perhapsŠThe museum's argument is that these things are one-of-a-kind and we will curate them and you won't. But I think it is possible for these things to remain in churches and be properly protected."

|

|||||||

|

QUICK LINKS: Feature Stories | Dispatches | Photo Essays | Itinerary | Maps | About This Class

A project of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism made possible by the Scripps Howard Foundation. Comments? E-mail us. Copyright © 2002 The Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. |

|

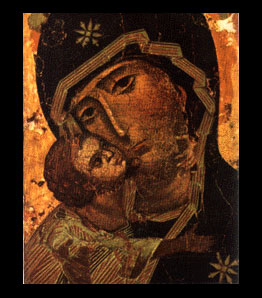

COURTESY OF MARIAN LIBRARY/INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE

The icon of Our Lady of Vladimir is considered to be an 11th century Byzantine work brought to Russia in the 12th century — a present from the Patriarch of Constantinople |

|

|