Turkey Explores the Internet, Along with Restrictions

By Allon Bar

Many countries censor the Internet, but under authoritarian regimes, such as China, censorship can be rampant. In Turkey, the censorship is not only affecting political activists, but average citizens as well. Access to the popular video-sharing site YouTube has been blocked since May 2008, and many blogs have been closed. A key role is being played by the new Internet law no. 5651. Turkey's restrictions on the world wide web offer three cases which illustrate the tensions between censorship and participatory democracy. One is the restriction on (political) speech, especially where constitutes an insult to "Turkishness" or Turkey’s founder, Atatürk. A second case corresponds to "citizen censorship," the involvement of citizens in the government’s censorship effort. The third is the crudeness with which websites are being blocked in Turkey.

Background

Categories of speech restriction are often reflective of social norms prevalent in a society. These social norms differ in quality and breadth by country. In the United States, the First Amendment allows for almost boundless freedom of speech, yet the federal government strongly fights display of child pornography. Moreover, there are private tools being used at homes and libraries, to provide additional social protection (sometimes called ‘CyberNannies’). For example, they may exclude content of nudity, or violence.

This research does not seek to impose an American First Amendment view on Turkey, but does seek to expose where tension exists between current practices and the needs of an open democratic society.

Turkey’s restrictions of freedom of speech have come under heavy scrutiny from the European Union, to which Turkey aspires to become a member. Censorship – restricting freedom of expression – has a long history in Turkey. Many of the current controversies regarding freedom of expression concern Turkish penal code 301, which penalizes "insults to Turkishness." Reporters Without Borders has dubbed this code “the enemy of press freedom”. The trials against the author (now Nobel Prize winner) Orhan Pamuk in 2006 and the (since-murdered) Armenian-Turkish newspaper editor Hrant Dink, both accused of insulting Turkishness, were cases in point. More recently, under article 301, a Turkish publisher was sentenced to five months imprisonment for publishing a book which calls the Armenian tragedy of the early twentieth century a genocide.

Many of Turkey's most controversial debates thus concern the issue of Turkey’s identity: its founding by Atatürk, the role of minorities in society (mostly focused on Kurdish Turks and the outlawed Kurdish Workers Party, PKK) and the massacre of Armenians in the period preceding the founding of modern Turkey, around 1915. These issues provoke most of the political censorship. Some Kurdish newspapers are forbidden, due to alleged PKK links. As stated earlier, mentions of the "Armenian genocide" has led to incidences of censorship and court cases. These trends are also reflected in Internet censorship.

Insulting Atatürk and Turkishness

In May 2007, Turkey’s president signed Bill 5651 into law. Until then Internet was regulated under the same terms as other media, but this bill provided further specifications as to what was not allowed online. The new "no-go" criteria were: encouraging suicide; sexual abuse of children; facilitation of drug abuse; provision of dangerous substances for health care; obscenity; prostitution; gambling; or crimes regulated in Turkish Code 5816 (crimes against Atatürk). It is especially the last of these crimes which transgresses social norms that are commonplace in most other countries. Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk – Father of the Turks) was the founder of the modern Turkish republic (Wikipedia), and remains the country’s national hero. Insulting him or his memory is considered a grave misdeed in Turkey.

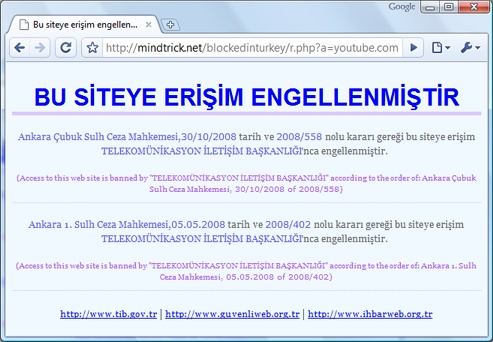

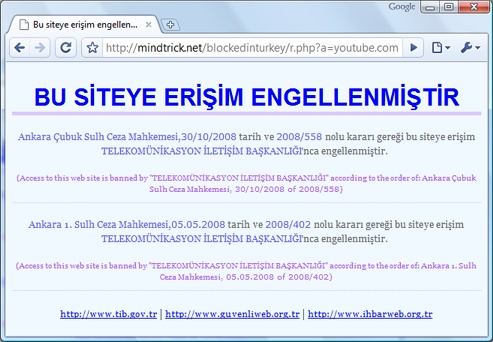

YouTube.com when accessed from Turkey (the result is a censorship notice). Web proxy simulation through http://mindtrick.net/blockedinturkey.

Turkey's response to insults to Atatürk were became evident in March 2007, when Turkey blocked access to the popular video-sharing website YouTube, after a Greek-Turkish cyber-conflict erupted on the site. Pro-Greek web surfers posted videos depicting Atatürk as homosexual, and Turkish video-posters responded in kind. Since then the site has been blocked off and on. As of May 2008, no Turkish Internet user has had access to YouTube through regular means, except, apparently, the Prime Minister. Although YouTube removed a number of contentious videos, it did not adhere to the Turkish demand to open a local representation in Turkey and thus further submit itself to accountability there.

The obvious consequence of the blockade is that Turks are no longer able to join in the exchange of videos that YouTube provides. The key of the YouTube revolution was its ability to provide drive space and access to videos of private persons, but today more and more organizations are using the platform for their video content. Turks are therefore excluded from an important part of information on the web, and cannot actively contribute to it either (by posting videos). The earlier-mentioned Orhan Pamuk has described the block on YouTube as "political " and commented on it at the Frankfurt Book Fair in October 2008: “Those in whom the power of the state resides may take satisfaction from all these repressive measures, but we writers, publishers, artists feel differently, as do all other creators of Turkish culture and indeed everyone who takes an interest in it: oppression of this order does not reflect our ideas on the proper promotion of Turkish culture.”

Also noteworthy are two of Turkey’s attempts to reach beyond its territorial borders. The first is requesting YouTube to make specific videos inaccessible worldwide (and not only to Turkish web surfers). The second is seeking extradition of posters of some of those YouTube videos. The latter request is not entirely new: for example Germany and Austria have sought extradition of people who violated their speech laws outside their borders, by denying the Holocaust. But the former notion, seeking to enforce its national view on the worldwide audience of YouTube, certainly has novelty to it. On what grounds could Turkey make this request, one could ask: as the guardian of the memory of its former president? Or out of a perception that national laws should find universal application? Both claims are – at a minimum – dubious.

Citizen Censorship

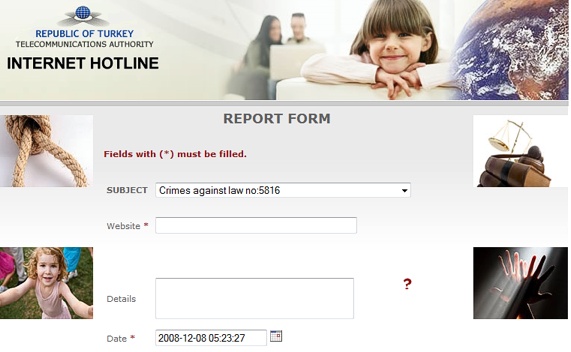

The role of citizen activists in censorship is another interesting aspect of Turkey’s Internet restrictions. Whereas in authoritarian regimes censorship may be instigated and implemented from above, Turkey encourages a "democratization of censorship." Private Internet users have the option to file complaints about specific websites. In fact, Internet users are encouraged to do so by using the “hotline” to alert the Telecommunications Authority, the government agency that is supposed to implement the Internet law 5651. Violations of the law can be reported to the agency through a telephone number, by e-mail, or by filling in a simple web form on its website: http://www.ihbarweb.org.tr.

Web users worldwide can report not only on 5651-violating websites, but also about an e-mail, newsgroup, instant messaging, chat, P2P or other. Even in private chat conversations, therefore, an insult of Atatürk could lead to government action, something hardly reassuring for both freedom of speech and privacy advocates. As of August 2008, over 20,000 individual complaints had been made.

Screenshot of the Telecommunications Authority's Internet Hotline

Screenshot of the Telecommunications Authority's Internet Hotline

The imagery on the Internet hotline’s website is telling: pictures of children and families. In the words of the Turkish minister of transportation: “websites will continue to be banned as long as they post content considered inappropriate for Turkish families”. The transportation minister encourages self-censorship, taking into account the "precautions" that law 5651 would prescribe. That brings back the dimension of societies desiring to protect their distinct norms. Yet some of these restrictions can be seen as infringing on the individual right of every human being (to express oneself, to access information, to exchange ideas). Human rights advocates would therefore urge caution. Such involvement of citizens in censoring efforts is nevertheless hardly unique to Turkey. According to Reporters Without Borders, the same happens in Thailand, China and Arabic countries.

This issue raises several questions. If a democratically elected government chooses to censor specific items – therefore presumably executing the chosen will of a country’s citizens – should that be acceptable? An objection to that may be that such policies may affect rights that are so fundamental to human beings, that no government should be allowed to restrict them (and thus not to impose a ‘tyranny of the majority”). Also, if a few citizens, by complaining, diminish the liberties of an exponential number of other citizens, should this infringe upon an individual’s right to gain or publish information? Proponents would argue that the hotline does not serve to find, but merely alert the authorities to websites that actually violate the already established law. However, an objection to that is that it restricts the ability for a free exchange of information and dialogue, essential functions for an effective democracy. Furthermore, one could argue that by censoring, citizens do not get to see what is being censored. To truly assess as a citizen whether a certain view is really subversive, one should be aware of what that view is. And that brings us to the last objection: censoring too easily provides a sliding scale of Internet discourse and a society with an increasing number of black holes.

The Blunt Instrument of Censorship

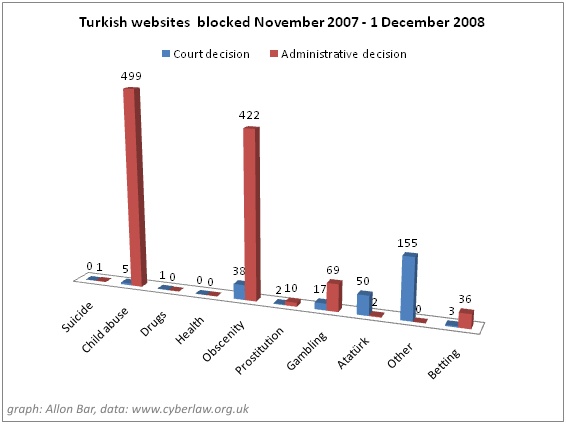

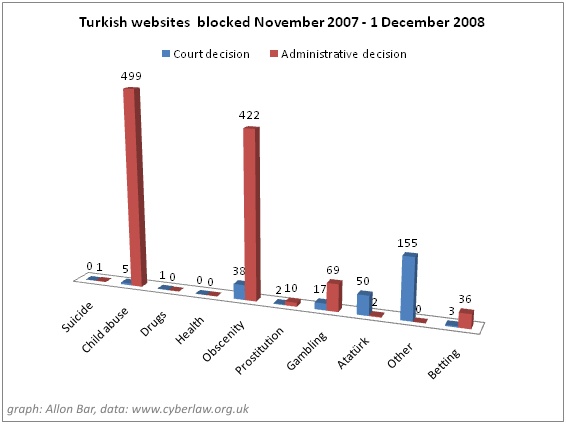

The role of citizens in censoring sites would perhaps be less of an issue were it not for the crudeness with which sites are being blocked in Turkey. As of December 1st, 2008, 1310 websites were blocked, a majority of which for obscenity (porn), child exploitation, but also a few dozen for insulting Turkishness and other violations.

source: http://cyberlaw.org.uk/2008/12/03/turkish-website-blocking-statistics-as-of-01-december-2008

Clothilde Le Coz of Reporters Without Borders said in a phone interview that it is remarkable with what ease sites are being blocked in Turkey. Not only does it appear there is little prudence in applying censorship, its reach often also transgresses what is considered the actual violation of the law. In numerous instances, and as noted with regards to the Atatürk videos on YouTube before, entire sites are shut down for selective pieces of content on it. Or as the academic Mustafa Akgül phrases it: “It's like finding two pages in a book illegal and reacting by closing down the entire library” (quoted in Today’s Zaman).

That brings us to an important case in point: the private mission of creationist writer Adnan Oktar (pen name: Harun Yahya) to block websites. Oktar, who claims his work has caused a serious decline in evolutionist belief in Europe, has used legal proceedings to close down several websites in Turkey, on charges of libel. Reporters without Borders estimates that nearly sixty websites have been made inaccessible at the request of Oktar. Examples include Wordpress (an important worldwide blogging service provider), the website of evolutionist writer Richard Dawkins, the site of the Turkish Educational Personnel union, and quite a few notable others. In the case of WordPress the content of a few blogs on its domain containing texts unfriendly to Oktar led to the entire WordPress domain to be blocked as of August 2007.

The same happened in October 2008 (but just for a few days) to Blogger.com and Blogspot.com, the biggest blog services worldwide. The court order to block those domains was sought by Digiturk, which saw its property rights on streaming football videos being violated by blogs posting those videos.

Web Surfer Response and Transparency

Such occurrences of censorship have been a sticking point for Turkish web activists, but also common Turks, who have thus been rendered unable to read their favourite blogs or publish information, including simple diaries. They have responded in various ways to the blockades: in August around 500 Turkish web sites shut themselves down to protest the censorship. But perhaps of more relevance to most Turks: many have started using proxy servers and other tools to be able to access the desired websites after all. That does not mean that access is full-fledged: posting videos on YouTube remains a problem even with such tools.

From a philosophical standpoint, it may be worthwhile asking, what is worse? Censoring an entire website, thereby making clear that something is being restricted? Or the "Chinese alternative," selectively removing or filtering? From a practical standpoint, some would argue that these are two sides of the same coin: both restrict speech where it should be unhampered. Both restrict the free exchange of ideas, where Internet should serve as the tool for dialogue and as a marketplace of information.

Another remarkable aspect of Turkey’s web censorship is that on every blocked website, an official notice is posted announcing its censure to web surfers. The notice includes the court or government order number, and other applicable information. That at least offers some clarity to Internet users as to why the site they seek to access is inaccessible. It will, however, not alleviate the problem of censorship in the first place. In fact, so argues Clothilde Le Coz, such transparency may encourage complacency over censorship in a country, as it will make a point that everything at least happens in an orderly and rule of law fashion.

Analysis

The above-mentioned topics point to some of the contentious debates on freedom of the Internet in Turkey, especially from a human rights perspective. For some Turks, bans on YouTube and blogs not only further damage Turkey in its international reputation (making it seem a backward country which engages in "childish" policies in order not be insulted), it more importantly impedes Turkey’s efforts to gain EU membership. The EU accession process will put extra pressure on the debate, which is principally a domestic one. Members of the European Parliament are already urging Turkey to rescind its ban on YouTube and other sites, to keep it off the A-list of pariah states repressing the Internet.

Turkey does not block views that are unfavourable to the government, nor does it imprison those who voice such criticism. For such reasons, Reporters without Borders will not define it an “enemy of the Internet” (a state which extends its repression offline to the online realm). It does however, potentially, imprison those whose views can fit in the stretchable category of “insulting Turkishness,” it blocks sites with relative ease and extensiveness, tries to exert Internet jurisdiction outside of its territory, and seems to have little regard for freedom of the Internet as a basis. The tendency to censor instead of protecting civil liberties may be reflective of seeing itself as being vulnerable. Perhaps no country should be forced to face up to difficult passages of its history, yet perhaps no country should disable its citizens’ ability to do so. Without a doubt, the debate over freedom of speech in Turkey will bring forth further views on these issues, as forces of rule of law, human rights, democracy, protection of societal norms and security attempt to balance each other.

Further reading

General links on Internet freedom

source: http://cyberlaw.org.uk/2008/12/03/turkish-website-blocking-statistics-as-of-01-december-2008

Clothilde Le Coz of Reporters Without Borders said in a phone interview that it is remarkable with what ease sites are being blocked in Turkey. Not only does it appear there is little prudence in applying censorship, its reach often also transgresses what is considered the actual violation of the law. In numerous instances, and as noted with regards to the Atatürk videos on YouTube before, entire sites are shut down for selective pieces of content on it. Or as the academic Mustafa Akgül phrases it: “It's like finding two pages in a book illegal and reacting by closing down the entire library” (quoted in Today’s Zaman).

That brings us to an important case in point: the private mission of creationist writer Adnan Oktar (pen name: Harun Yahya) to block websites. Oktar, who claims his work has caused a serious decline in evolutionist belief in Europe, has used legal proceedings to close down several websites in Turkey, on charges of libel. Reporters without Borders estimates that nearly sixty websites have been made inaccessible at the request of Oktar. Examples include Wordpress (an important worldwide blogging service provider), the website of evolutionist writer Richard Dawkins, the site of the Turkish Educational Personnel union, and quite a few notable others. In the case of WordPress the content of a few blogs on its domain containing texts unfriendly to Oktar led to the entire WordPress domain to be blocked as of August 2007.

The same happened in October 2008 (but just for a few days) to Blogger.com and Blogspot.com, the biggest blog services worldwide. The court order to block those domains was sought by Digiturk, which saw its property rights on streaming football videos being violated by blogs posting those videos.

Web Surfer Response and Transparency

Such occurrences of censorship have been a sticking point for Turkish web activists, but also common Turks, who have thus been rendered unable to read their favourite blogs or publish information, including simple diaries. They have responded in various ways to the blockades: in August around 500 Turkish web sites shut themselves down to protest the censorship. But perhaps of more relevance to most Turks: many have started using proxy servers and other tools to be able to access the desired websites after all. That does not mean that access is full-fledged: posting videos on YouTube remains a problem even with such tools.

From a philosophical standpoint, it may be worthwhile asking, what is worse? Censoring an entire website, thereby making clear that something is being restricted? Or the "Chinese alternative," selectively removing or filtering? From a practical standpoint, some would argue that these are two sides of the same coin: both restrict speech where it should be unhampered. Both restrict the free exchange of ideas, where Internet should serve as the tool for dialogue and as a marketplace of information.

Another remarkable aspect of Turkey’s web censorship is that on every blocked website, an official notice is posted announcing its censure to web surfers. The notice includes the court or government order number, and other applicable information. That at least offers some clarity to Internet users as to why the site they seek to access is inaccessible. It will, however, not alleviate the problem of censorship in the first place. In fact, so argues Clothilde Le Coz, such transparency may encourage complacency over censorship in a country, as it will make a point that everything at least happens in an orderly and rule of law fashion.

Analysis

The above-mentioned topics point to some of the contentious debates on freedom of the Internet in Turkey, especially from a human rights perspective. For some Turks, bans on YouTube and blogs not only further damage Turkey in its international reputation (making it seem a backward country which engages in "childish" policies in order not be insulted), it more importantly impedes Turkey’s efforts to gain EU membership. The EU accession process will put extra pressure on the debate, which is principally a domestic one. Members of the European Parliament are already urging Turkey to rescind its ban on YouTube and other sites, to keep it off the A-list of pariah states repressing the Internet.

Turkey does not block views that are unfavourable to the government, nor does it imprison those who voice such criticism. For such reasons, Reporters without Borders will not define it an “enemy of the Internet” (a state which extends its repression offline to the online realm). It does however, potentially, imprison those whose views can fit in the stretchable category of “insulting Turkishness,” it blocks sites with relative ease and extensiveness, tries to exert Internet jurisdiction outside of its territory, and seems to have little regard for freedom of the Internet as a basis. The tendency to censor instead of protecting civil liberties may be reflective of seeing itself as being vulnerable. Perhaps no country should be forced to face up to difficult passages of its history, yet perhaps no country should disable its citizens’ ability to do so. Without a doubt, the debate over freedom of speech in Turkey will bring forth further views on these issues, as forces of rule of law, human rights, democracy, protection of societal norms and security attempt to balance each other.

Further reading

General links on Internet freedom