Kenya, Mexico, Al-Qaeda: New Media and Violence

When Kenya erupted after the December 27, 2007 presidential elections, new media practitioners were quick to document the violence and human rights abuses throughout the country and to share their observations with the world. After the government instituted a media blackout on December 30, banning all television and radio broadcasts, bloggers like M. of Thinker’s Room and R. of What an African Woman Thinks posted near-daily updates on the crisis as it unfolded. Their accounts, coupled with the data on post-election violence from Ushahidi, a web site created in January 2008 that allowed Kenyans to report instances of violence via e-mail or SMS, gave the world a picture of what was happening in the country at a time when traditional media was unable to access or report on the crisis.

Stories like these make it easy to praise the role technology, particularly digital media, plays in the developing world. The ease with which Internet and mobile-phone equipped citizens can take an active role in the global flow of information, as well as governments’ relative inability to stop them, make citizen journalism one of the fastest ways to spread information during a crisis. However, the technology that makes the work of citizen journalists and human rights activists easier is not limited to use by those with altruistic goals. The same tools can be and have been used to spark violence and fear.

Kenya: SMS Campaigns for Violence

Blogs, mobile phones, YouTube and other digital services were instrumental in documenting post-election violence in Kenya and in sharing this information with a global audience during an otherwise total media blackout. However, according to a

recent study of new media in post-election Kenya, mobile phones were also used to coordinate riots and attacks on various ethnic groups.

Text messages inciting ethnic violence started to spread as early as January 1, 2008, urging Kenyans to “deal with them [incumbent president Mwai Kibaki’s tribe, the Kikuyu] the way they understand…violence.” Messages in response called on the Kikuyu to “slaughter them [members of opposition candidate Raila Odinga’s tribe, the Luo] right here in the capital city.”

Less sinister but just as dangerous were messages warning friends of impending riots, some of which, according to a

post on What an African Woman Thinks, caused preemptive attacks by people who believed they were “merely being offensive in their own defense”. The author draws a parallel between the calls to genocide on Radio Rwanda in 1994 and the violent SMS campaigns in Kenya:

It is one thing to broadcast subversive messages on Radio as was the case in Rwanda, and is

alarmingly the case with some vernacular radio stations in Kenya. It is an entirely different

thing to send these messages to a carefully selected list of people on your contact list who

will in turn send them on to their own select list of people so that the message spreads like

a virus but catches only people who answer to certain ‘characteristics.’

Kenya: Hate Speech Online

Hate speech was not limited to mobile phones. The Kenyan online forum

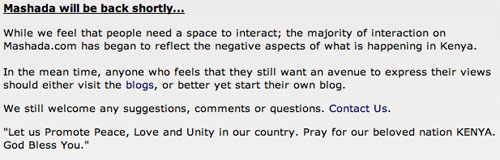

Mashada became so filled with violent messages that its creator, David Kobia, shut it down on January 29, 2008. A

screenshot taken of the forum that day reads, “While we feel that people need a space to interact; the majority of interaction on Mashada.com has began to reflect the negative aspects of what is happening in Kenya”:

In an

interview several months after the elections, Kobia noted that the media blackout caused many Kenyans to look for information online. He called the freedom of expression offered by Mashada a “double-edged sword,” admitting that it allowed people to share “imagined account[s] of the truth” and that for those with “the intent to spread ethnic vitriol on the website…this is a microphone.”

Kobia's decision to temporarily close the forum was met largely with support from the Kenyan blogosphere. Ory Okolloh of Kenyan Pundit

wrote, “David, I’m sure this was a difficult step, but very much a necessary one. For those who are defending the right to free speech or to be aware of “situations”…I draw the line when that kind of speech is fueling the killings we are seeing in Kenya. No apologies.”

The speed with which Kenyans turned to digital technology in the aftermath of the 2007 elections is proof that the Internet and mobile phones are increasingly shaping the ways in which crises play out in the developing world. However, the double-edged sword of technology extends beyond crisis situations.

Mexico: Virtual Kidnappings

In Mexico, mobile phone-based “virtual kidnappings” have risen exponentially in the last year. Perpetrators, often convicted criminals using smuggled mobile phones, call parents and pretend to be holding a child hostage when the child is unreachable – in a movie theatre, perhaps, or with a dead cell phone battery. The victims will hear screaming or crying in the background, and the perpetrators will demand ransom before the whereabouts of the child can be determined. Police received

over 30,000 complaints of virtual kidnappings between December 2007 and February 2008, and

recent reports from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement suggest the phenomenon is spreading into the United States. Virtual kidnappings have been linked to other cell phone scams similar to e-mail spam, including fake lotteries, and a coordinated virtual kidnapping attack against members of the Mexican legislature shut down Congress for a day in November 2007.

Al-Qaeda: Recruitment and Propaganda

Even al-Qaeda, a group whose rigid adherence to fundamental Islam and self-professed hatred of Western culture is seemingly inconsistent with the modern technology that culture has developed, is using the Internet as a tool for recruitment and propaganda. In 2002 the BBC

reported, “A widespread network of websites are energetically feeding information from those at the top of the terror organisation to supporters and sympathisers around the world” , and Jarret M. Brachman, the Director of Research at the Combating Terrorism Center at the United States Military Academy,

notes that “One can even pledge allegiance to Osama bin Laden by filling out an

online form.”

Conclusion

Digital media, as evidenced by the articles on the rest of this web site, has the power to connect communities across geographic divides, enhancing creative collaboration, providing better education and health care, documenting and preventing human rights abuses and equipping development practitioners with the tools they need to accomplish and promote their work. The aspects of new technology that make it useful in each of these situations, however, also make it easily adaptable for hurtful purposes. In order to understand how best to utilize digital media for good, we must also understand how it is used for harm.