Compiled by John Edward Felbinger

In this document I undertake to expand the information about the Prahl and related families found in Schlegel's

German-American families in the United States, Volume 3, pp. 81-86. Having studied Schlegel for some

time, it is my sincere belief that my grandfather Edward Lloyd Stephen Prahl (December 5, 1882--March 6, 1966) was the

principal informant, aided perhaps by other members of the family. This conviction is as much an intuitive assessment

based upon personal knowledge of details of my grandfather's life as well as any specific factual information

contained in Schlegel. Of course, "Grampa" himself knew only certain things, did not have access to various documents,

or (in a few instances) was simply mistaken. And: there is no accounting for the faulty editing and factual errors

that creep into a work as magisterial as Schlegel; that there are handwritten emendations in the "family" copy is

sufficient evidence of this. Last, Schlegel traces the family only to 1917; as of this writing, that is almost 90

years past. This fact alone explains the complete absence in Schlegel of any

mention to Grampa's younger daughter, my aunt Christine Ella Prahl (March 1,1919-February 23, 2003; married August Louis

Oechsli, September 9, 1939).

To facilitate my emendations to Schegel, I will organize them into a series of chapters, often with subsections. I will begin each chapter and subsection with a quotation that cites what part of Schlegel I am expanding, revising or correcting. When appropriate, I will also provide supplementary information to put certain events into larger historical contexts.

Finally, this document is effectively "a work in progress", or "integrating resource" as the library trade call these things. It represents the state of my research at any particular time, and as such will be revised and updated on an on-going (though most probably, irregular) basis. Anyone consulting this document should return from time to time, to learn of any improvements. -- JEF, begun October 8, 2005

-------------------------------------

Contents

Chapter I. The origins of the Prahl family.

Chapter II. Charles Prahl.

Chapter III. Charles Edward Prahl.

Chapter IV. Edward Alfred Prahl.

Chapter V. Edward Lloyd Stephen Prahl.

Chapter VI. The Blaicher family.

Chapter VII. The Merkel family.

-------------------------------------

Chapter I. The origins of the Prahl family.

Section A: General history.

"Johann Siebmacher, a noted German heraldist ..." -- Schlegel, v. 3, p. 81.

In 2003, I started to research the specific references listed in "Siebmacher". Good librarian that I am, I discovered quickly through perusal of the OCLC and RLIN national bibliographic databases that Siebmacher himself died in 1611. His name has become a convenient "handle" for anyone wanting to continue and expand his original work on German heraldry. Happily, the Genealogical and Local History Division of the New York Public Library (herefter GD-NYPL) has many of these volumes. In: Jäger-Sunstenau, Hanns. General-Index zu den Siebermacher'schen Wappenbüchern 1605-1961 (Graz : Akad. Druck u. Verlagsanstalt, 1964), I found several references to "Prahls" similar to those listed in Schlegel, but in my opinion the references are probably of little or no immediate relevence to research into my branch of the Prahl family. As is often the custom in genealogical books, Schlegel expands the lack of information about specific individuals by writing about the family in general: in this case, making the point that the "Prahls" (with several variant spellings) are "of ancient Teutonic origin", etc., and that several people with the same name have done remarkable things in their lives. Such information is, of course, interesting in its own right, but can detract from the business at hand.

Section B: Prahl heraldry.

"Following is the description of the Prahl coat-of-arms, which Claus Prahl, living in the Free City of Hamburg, in 1653, received as Bürger Captain ... "--Schegel, v. 3, p. 81.

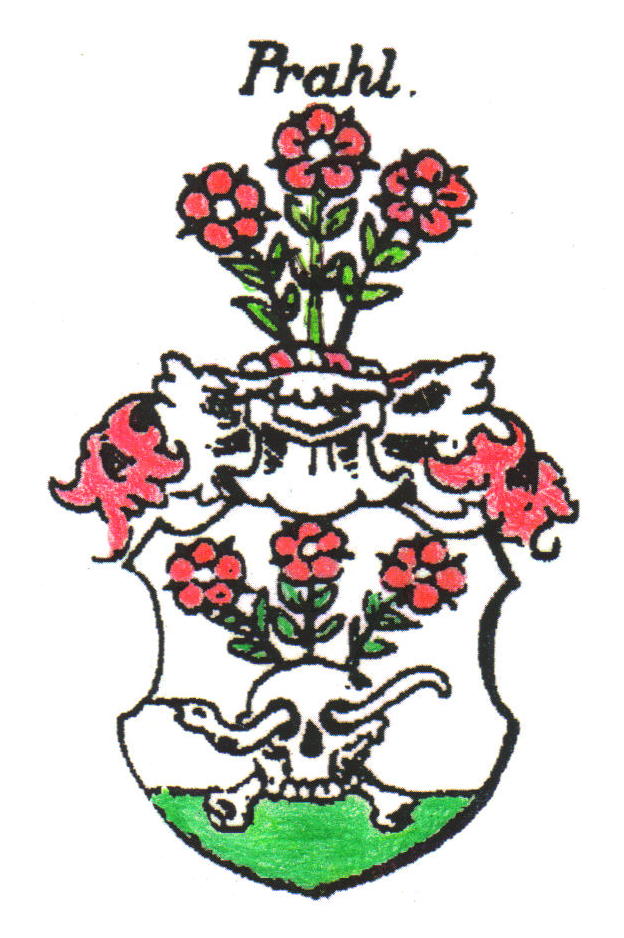

The several editions and volumes of Siebermacher in the GD-NYPL are not the easiest reference books to use, as they have been supplemented with little internal reference structure. The NYPL librarians complained of their general want of success with them. On the initial search, I fared little better. Exploration of other heraldic reference works did turn up one rendition of the coat-of-arms (displayed in: Hamburgische Wappenrolle / nach Hamburgischen Wappenbüchern zusammengestellt von Eduard Lorenz Lorenz-Meyer. (Neustadt/Aisch : Bauer & Raspe, 1976; originally published 1912 -- p. 109)):

When one has only one picture, one takes what one has. Unfortunately, a close reading of Schlegel's quotation from

Siebmacher reveals that this rendition of Claus Prahl's shield is not particularly accurate: it does not take into

account the green and silver on the shield, and is missing the snake threaded through the eye-sockets of the skull.

More intense research in Siebmacher in January 2004 finally turned up its rendition of the shield with a description in German, which Schlegel translates into English. In: Seyler, Gustav Adelbert. Die Wappen bürglicher Geschlechter Deutschlands und der Schweiz. (Neustadt a.d. Aisch : Bauer & Raspe, 1972) -- (J. Siebmacher's großes Wappenbuch ; Bd. 10). "Reprographischer Nachdruck von Siebmacher's Wappenbuch, V. Bd., 4.-6. Abt. Nürnberg 1890, 1895, 1901: -- Abt. 5, p. 30, Tafel 36), I found the following image. The image itself, like the one preceding, is presented in Siebmacher in black-and-white. Here, to present the image with its full effect, I hand-colored the image according to its description before scanning it into the computer. Below the image I have recorded the German description as it appears in Siebmacher. The English version in Schlegel (quoted here again) translates the German into standard heraldic terminology. For those like myself who are not generally familiar with that terminology, I have also added a more everyday-English translation.

Argent, a base vert, a skull and cross bones proper, through the eyes a snake faced dexter,

from the crown of the

skull three roses slipped and leaved, all proper.

Crest: Three roses slipped and leaved proper. Mantling gules and

argent. -- Schlegel, v. 3, p. 81.

Silver on a green base; above, two bones and a skull, through which eyes a snake slithers.

From the skull grow

three green-stemmed red roses.

The helmet: three stemmed roses. The cloth cover: red and silver. -- Felbinger

EXCEPT for some additional promotions, I have no further information concerning Claus Prahl. Customarily,

coats-of-arms are awarded to non-noble persons for extraordinary services rendered to one's country. It is a safe

guess therefore that Claus Prahl rendered to the Free City of Hamburg some service that merited award of a

coat-of-arms. Usually, the design of the shield has some significance for the bearer; here, one can only imagine what

significance the "skull-and-crossbones" might have held for Claus Prahl. In any event, the coat-of-arms was for his

use only (and whether for his descendants also I do not know). Thus, it is good to know that one member of the larger

Prahl family was so honored, but to the best of my knowledge the shield is not hereditary.

Chapter II: Charles Prahl.

"Charles (Karl) Prahl, the first representative of this branch of the Prahl family of whom we have any authentic information ... " -- Schegel, v. 3, p. 81.

In 2003 I began to research my mother's family, the Prahls, where heretofore I had concentrated on the Felbingers. Almost immediately I was confronted with several obstacles to my research.

Section A: "Alteslohe" = "Bad Oldesloe".

The first obstacle was a very basic one: from whence did the Prahls *really* emigrate? I quote the above sentence more fully: "Charles (Karl) Prahl, the first representative of this branch of the Prahl family of whom we have any authentic information, was born in the town of Alterslohe, in the Duchy of Holstein ... in 1826." A search of several databases, such the GEONet Names Server created by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, and examination of several German road-map atlases revealed no town by the name of "Alterslohe". Nor was I helped by a letter dated August 1, 1952 by Emma Hagedorn, a daughter of Adelaide (Prahl) Hagedorn. I believe the letter was written most probably to Mildred (Dickinson) England, daughter of Adelaide (Prahl) Dickinson and William B. Dickinson, and Mildred passed on the letter (or a copy) to her first cousin, my mother Constance (Prahl) Felbinger. I have a xeroxed copy of the letter in my possession, and about this letter I will have more to say later on. Immediately, Emma Hagedorn states the name of the town where her mother was born as "Attesle". A search under this form also yielded no results. This lack of success led me to a fruitless search of maps of the Hamburg area, looking for "Alterslohe/Attesle" as a local place name, such as a district or neighborhood.

A break came finally in examining several web sites relating to the genealogy of Schleswig-Holstein. The suggestion was that the name might be "Oldesloe", now Bad Oldesloe. About this same time I was searching for Prahl documents in the New York City Municipal Archives, and realized that the records of one person, Charles Prahl's oldest daughter Adelaide (married Hagedorn), born in "Alterslohe" and brought to America as a child, might hold the key. Her death certificate indicates only that she was born in Germany. I was determined to find her marriage certificate, as it would be the one time (unlike birth and death) that she could speak for herself. Happily, I found it, and it states that she was born in "Oldesloe": success! Also at this same time I found the web-sites of Peter Doerling, who is active in the genealogy of Kreis Stornarm, in which Bad Oldesloe is located. Among other information found on Doerling's web-sites (including several Prahls), he notes that "Oldesloe" has an alternative name, "Altenschloo", that I can only consider to be the local, *Low* German pronounciation of "Oldesloe". Such pronounciation(s) would solve the mystery of the mistaken place-name in Schlegel. My grandfather, Edward Lloyd Stephen Prahl, hearing the name spoken by his grandfather Charles, and Cousin Emma Hagedorn hearing the name spoken by her mother Adelaide (Prahl) Hagedorn (who, though born in Oldesloe, only heard the pronunciation from her parents Charles and Frederika), and neither Edward nor Cousin Emma having sufficient knowledge of German (never mind Low German), garbled the name in transmission. Lastly, Schlegel did not verify the name.

Section B: The Prahl Family in Oldesloe: Vital Records

In November 2003 I traveled to Bad Oldesloe to see the town where the Prahls came from, and to the neighboring city of Bad Segeberg to examine the church books located in the Kirchenbuchamt, Ev.-Luth. Kirchenkreis Segeberg, Kirchstr. 9, Bad Segeberg. Following below are the results of my research. Having really only one day to look at records, I naturally decided to concentrate as much as possible on Charles Prahl and his immediate family. Records gleaned from even so short a visit opened up the possibility for additional research at a later time. I have listed the registers in which I found various vital records. I have attempted to retain the original spelling and even the formatting of the records, to give readers some sense of the original records. If something might be unclear, I have added a clarifying phrase or the word "sic", all in square brackets [...]. After presentation of the vital records, I will summarize their contents in English in Section C.

A. Index: Prahl, Karl Friedr. Heinr. Uhrmachr *7.7.1802 Rendsburg, Konf. 1819/14; cop. 1825/54

Joh. Martha gb. Lundt *25.1.04, Konf. 1817/28, +21/12 52

B. "Copulationsregister des Jar 1825"

"54. 28 Nov. Carl Friedrich Heinrich Prahl, Uhrmacher in Oldesloe,

des weil. Lieutenants in Oldesloe Johann Friedrich Andreas v. Prahl,

u. der Anna Sophia Maria, geb. Linden, Sohn. Mit Johanna Martha Lund,

des weil. Müllers in Oldesloe Christian Matthisen Lund u. der Anna Christina,

geb. Jürgensen, copbr. Des Brautigams Vaccinationsattest

war von Doctor Keil geschrieben und datiert, Rendsburg den 4. April 1818."

C. "Duplicat des Geburts und Taufsregister von October 1826 bis Dezember 1830"

"Anno 1826."

"299. [Tag des Geburts] 19. Sept. [Tag der Taufe] 31. Oct. Carl Johann Hans Prahl in Oldesloe.

Aeltern: Carl Friedrich Prahl, Uhrmacher hs. u. Johanna Martha geb. Lundt, 1tes Kind.

Taufzeugen:

1. Carl Friedr. Lundt,

2. Hans Jürgensen,

3. Joh. Samuel Adam Mühlhausen,

alle aus Oldesloe"

"Anno 1828."

"92. [Tag des Geburts] 3. April [Tag der Taufe] 18. April. Ernst Hermann Wilhelm Prahl in Oldesloe.

Aeltern: Carl Friedrich Heinrich Prahl, Uhrmacher hs. Johanna Martha geb. Lundt 2tes Kind, beide leben.

Taufzeugen:

1. Carl Friedr. Wilhelm Prahl,

2. Joach. Herm. Hormann,

3. Wilhelmine Nielandt,

alle in Oldesloe"

"Anno 1833."

"183. [Tag des Geburts] 11. Jul. [Tag der Taufe] 24. Jul. Johanna Sophia Friedrika Prahl in Oldesloe.

Aeltern: Carl Friedrich Heinrich Prahl Uhrmacher hs. Johanna Martha geb. Lundt.

Taufzeugen:

1. Anna Maria Sophia Prahl,

2. Johanna Christina Mühlhausen,

3. Adolphina Friederika Wulf,

alle in Oldesloe"

D."Geburts- und Taufregister: Anfang 1846 bis Juli 1856"

"Geborene im Jahr 1850"

"340. [Tag des Geburts] Dec. 20 [Tag der Taufe] Feb. 4. Adelaide Johanna Friedrike Prahl

in Oldesloe des Uhrmachers hierselbst Carl Johann Hans Prahl und Friederike Henrietta Anna geb. Storch

ehel. Tochter 1tes Kind.

Taufzeugen:

1) Johanna Martha Prahl aus Oldesloe,

2) Anna Maria Friederika Storch,

3) Adelaide Eugenie Charlotte Brons,

beide aus Kiel."

"Geborene im Jahr 1852"

"186. [Tag des Geburts] Mai 29 [Tag der Taufe] Juli 2. Johanna Maria Mathilda Prahl

in Oldesloe, des Uhrmachers hierselbst Carl Johann Hans Prahl und Friederike Henrietta Anna geb. Storch

ehel. Tochter 2tes Kind.

Taufzeugen:

1) Johanna Sophie Friederike Prahl, in Oldesloe,

2) Maria Dorothea Johanna Christine Schmidt, in Oldesloe,

3) Wernerine [sic] Mathilda Lundt aus Schleswig.

E.Tod-Register. 1852 -- "201. [Todestag] Dec 21 [Tag der Begrabung] Dec 27. Fr. Johanna Martha Prahl geb. Lundt in Oldesloe, des Christian Matthiesen Lundt und Anna Christina geb. Jürgensen ehel. Tochter, geb. 25 Jan. 1804, Ehefrau des Uhrmachers hierselbst Carl Friedrich Heinrich Prahl, hinterläßt diesen ihren nun verwittweten Ehemann und aus dieser Ehe 2 Kinder: 1) Karl Johann Hans, verheirathet mit Friederike Henriette Anne [sic] geb. Storch, und aus dieser Ehe 2 Kindeskinder: a. Adelaide Johanna Friederike, b. Johanna Maria Mathilda; 2) Johanna Sophia Friederike, unverheirathet. Sie starb in einem Alter von 48 Jahren und 11 Monathen. Notif. 6. Jan. 1853."

F. Copulatio. 1857 -- "36. Jun 3. Der Dr. med. Friedrich Meinroth Emil Berg, Bergenhusen, des ... zu Oldesloe

... Torbin Friederik Berg und Maria Christine geb. Luders ehel. Sohn (geb. 1815, 11 März) mit seiner Braut

Johanna Sophia Friederike Prahl in Oldesloe, des Uhrmachers hierselbst Carl Friedrich Heinrich Prahl, und Weib

Johanna Martha geb. Lundt ehel. Tochter (geb. 11 Jul. 1833 J.)

Zeugen:

1) Heinrich [?] Joachim Friedrich Berg zu Oldesloe,

2) Carl Friedrich Heinrich Prahl zu Oldesloe

..."

Section C. The Prahl family in Oldesloe: English Summary of German Vital Records (Section B).

The material presented in Section B above gives a good starting place for information concerning Charles Prahl and his immediate ancestors. Obviously, it is not the whole story because, to my knowledge, other documents are known to exist. Those immediately in my possesion I will present in Section D below; other documents, such as the Danish census records created quintennially during the period of the Prahls being in Oldesloe, and additional vital records in Bad Segeberg and other places, have yet to be examined.

A.Grandparents of Charles Prahl (Record B: "Copulationsregister des Jar 1825")

1. The paternal grandparents of Charles Prahl are: Johann Friedrich Andreas von Prahl, Lieutenant in Oldesloe; and his

wife Anna Sophia Maria, born Linden.

2. The maternal grandparents of Charles Prahl are: Christian Matthisen Lund, miller in Oldesloe; and his wife Anna

Christina, born Jürgensen.

A number of facts present themselves in this record. With all grandparents accounted for, and allowing minimally 20 years between generations, the approximate years of birth for Charles Prahl's grandparents might be sometime in the 1780s, perhaps 1770s. Dates and places of marriages and deaths are also unknown at this writing. Charles's paternal grandfather, Johann Friedrich Andreas "von" Prahl, already had the noble "von" added to his name, for what reason is at present unknown. His rank would indicate a military occupation of some sort. His maternal grandparents, Christian Matthisen Lund (also spelled "Lundt") and Anna Christina (born Jürgensen) are also interesting, for with such surnames they are surely of Danish origin. There was the belief long held in my family that the Prahls might be Danish as well as German, but this record search has confirmed the opinion with documentary evidence.

B.Parents of Charles Prahl (Record A, Index; Record B, "Copulationsregister des Jar 1825"; and Record E, "Tod-Register")

The parents of Charles Prahl are: Carl Friedrich Heinrich Prahl, watchmaker in Oldesloe; and his wife, Johanna Martha Lund (also Lundt). He was born July 7, 1802, in the city of Rendsburg, some 70 kilometers north of Oldesloe, and confirmed in the Lutheran faith in 1819. Johanna Martha Lund was born January 25, 1804, and confirmed in 1817. They were married on November 28, 1825 in Oldesloe. On an initial search, I found no record of Carl Friedrich Heinrich's death. Johanna Martha Prahl (born Lund(t)) died in Oldesloe on December 21, 1852, and was buried on the 27th; cause of death is not listed in the record.

C.Charles Prahl and siblings (Record C, "Duplicat des Geburts und Tausfregister von October 1826 bis Dezember 1830"; Record E, "Tod-Register"; and Record F, "Copulatio"

Charles Prahl was born on September 19, 1826, the first child of his parents. He was baptized on October 31st of the same year, and given the names of Carl Johann Hans Prahl, after his godfathers Carl Friedr. Lundt, Hans Jürgensen, and Joh. Samuel Mühlhausen. From this record it is obvious to deduce that he anglicized his name to Charles upon his arrival in the United States, and from American records that he chose not to use his other given names.

Charles Prahl had two younger siblings. The first, a brother, born April 3, 1828 and baptized Ernst Hermann Wilhelm Prahl on April 18th. The second, a sister, born July 11, 1833, and baptized Johanna Sophia Friedrika Prahl on July 24th. I found no records concerning other siblings who were born and died as infants or young children. For Charles's two siblings, I found no further record of the brother, Ernst Hermann Wilhelm Prahl. I noted that he is conspicuously absent from the death record for his mother, Johanna Martha Prahl. Such absence leads to the obvious conclusion that he predeceased his mother, but when and under what circumstance is unknown. The sister, Johanna Sophia Friedrika Prahl, later married a doctor, Friedrich Meinroth Emil Berg, born March 11, 1815, a man 18 years her senior, on June 3, 1857. Whether her brother Charles, by that time living in New York City, knew of the wedding is unknown.

D.Marriage and children of Charles Prahl, and Friederike Henrietta Anna Prahl, born Storch (Record D, :Geburts- und Taufregister: Angang 1846 bis Juli 1856")

My initial search turned up no record of the marriage of Charles and Friederike Henrietta Anna Prahl in the Oldesloe marriage records. Considering that Friederike (also known as Anna, cf. infra) was born in Kiel, it is most likely that the couple were married there or perhaps somewhere else. Additional research needs to be done in this matter.

Two children were born to Charles and Friederike Prahl in Oldesloe. The first child, a daughter, Adelaide Johanna Friedrike Prahl (later Hagedorn), was born December 20, 1850, and baptized February 4, 1851; she was named for her godmothers, of whom one was her grandmother, Johanna Martha Prahl. The date as presented in the German records is a whole year earlier than the date presented in Schlegel. My immediate thought is that my grandfather, Edward Lloyd Stephan Prahl, had a habit of referring to anyone's age as "being in his [her] Xth year". I often thought this a peculiar habit, perhaps derived from some custom in the Prahl family; it may well be a European custom. It often had the unfortunate tendency to throw off reckoning of a family member's age by a year. I suspect too that Grampa might have known little and nothing about his grandparents' second child, as there is no mention of her in Schlegel. The second child, a daughter, Johanna Maria Mathilda Prahl, was born May 29, 1852 and baptized July 2, 1852. She too was named for her godmothers, one of whom was Charles Prahl's sister, Johanna Sophie Friederike Prahl. Obviously, if the birthdate in Schlegel for Adelaide (known as Johanna, cf. infra) were accurate, it would be a biological impossibility for Johanna (known as Maria, cf. infra) to be born five months later: premature births were obviously not unknown, but the likelihood of such a child's survival in that pre-technological age would be slim indeed.

Section D: The Prahl Family in Oldesloe: additional records

I have in my possession two documents containing information about the Prahls and their related families, and about their lives in Oldesloe and other places. Certainly I make no claim for the accuracy of the information presented in these documents by the attestants, except insofar as I have been able to verify the information through other sources.

*****

THE FIRST DOCUMENT is a manuscript letter, signed; single sheet, 9 x 5 3/4 in., written on both sides. At the head is the company logo of H.F. Angle, Watchmaker and Jeweler, of Clinton, N.J. The letter, dated November 6, 1901, is written by Charles Prahl to "My dear girls" (his granddaughters Adelaide and Mathilda? The recipients are unnamed, and the letter is signed "With love Your Grandpa Charles Prahl") in response to a letter (also in my possession) asking if the Prahls are of Dutch origin and had perhaps fought in the American Revolution. In the letter, Charles Prahl states:

" ... our Family came from Scandinavia! My Grandpa your Great Grandpa was Sophus von Prahl and he was Mayor [sic] by the Danish Regiment "Oldenburg" and died on the Battlefield of Sehestedt in 1814."

Reading the entire letter, I am deeply touched that even after 104 years my great-great grandfather can reach out to say a few words about his ancestors and their lives 87 years before, during the Napoleonic wars. I imagine he was told these stories by his father, and how much more information Charles Prahl might have had can only be guessed at. It is clear that he is somewhat confused about the familial relationships, but as previously stated, it is not altogether clear who the recipients are, either. Concerning the battle of Sehestedt, my initial reading of the word was "Lehrstedt", but I found no battle by that name. Closer examination of Great-great-grandfather's handwriting yielded "Sehestedt" as a possible reading. Subsequent search on the Internet yielded more satisfactory results, including accounts of the battle itself told from the Allied side. The story of the Napoleonic wars is vast, and told in greater (and better) detail in other places. Following is a brief summary of my research from several Internet websites.

During the Napoleonic wars, the Kingdom of Denmark (which included Norway as well) attempted to remain neutral in the ongoing conflicts between France under the emperor Napoleon, and nations allied against him in several different coalitions, notibly England, Austria, Prussia and Russia. Denmark was at this time (even as now) not a great military power, but because of its strategic geographic position had considerable maritime and naval interests in the North and Baltic Seas. As a foreign policy, neutrality is however difficult to maintain when a nation's trade is being ruined by an ongoing war, and when the combatants are fearful that the neutral nation might decide for the enemy. England, with its vast naval superiority, was principally concerned that only British ships might make use of the ports of continental Europe, thus stifling French trade as an indirect means of combating Napoleon. In addition, England seized the cargoes of ships of neutral nations, including Denmark, when those ships were bound for ports the British Navy were blockading. In December 1800, exasperated by these tactics and pressured by Napoleon, Denmark joined Sweden and Russia in a league of armed neutrality that attempted to close all Baltic ports to English shipping. Denmark further aggravated the situation by seizing Hamburg, the principal German port through which English goods reached the continent. In retaliation, England sent a fleet to Copenhagen in 1801, destroying several ships in its harbor, as well as shelling the town and destroying coastal defenses. Denmark, Sweden and Russia quickly sued for peace. Meanwhile, Napoleon was successful in the next few years in bringing much of Europe under his control, and established the Continental System, for the purpose of excluding British shipping from European ports. England in turn declared further blockade of Europe, and in a another show of force again sent a naval fleet to Copenhagen in September 1807 to shell the city and destroy naval and commercial shipping in its harbor, even though Denmark was still neutral. Confronted with this situation and under constant pressure from Napoleon, Denmark finally allied itself with France and declared war on England in October 1807.

The war went on for Denmark for the next seven years. During that time, Denmark's principal responsibility was protecting Napoleon's northern flank, and covering his rear-echelon communication lines back to France, especially when Napoleon and the Grande Armee set off into Russia in the disastrous campaign of 1812. The following year 1813 found Napoleon on the strategic defensive, desparately trying to maintain his positions in Germany. The titanic battles at Dresden, Bautzen, and the final catastrophe at Leipzig in October saw the involvement of tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of men. Despite these reverses in French fortunes, however, the Danes remained loyal to Napoleon, even as other nations switched sides. In scale, Allied operations against Denmark were certainly not as vast in manpower, yet had their own raison d'etre as France continued to hold Hamburg. As part of clearing the French out of Hamburg, the Allies were also desirous to put Denmark out of the war.

Denmark was invaded in December 1813 through Schleswig-Holstein from several directions, by a Swedish

contingent moving along the coast from Mecklenburg-Pomerania, and by a mixed English-German-Russian force from further

south, advancing along the axis Oldesloe/Segeberg-Rendsburg/Sehestedt, advancing up the middle of the

Jutland Peninsula. The Danes, thinking their position in Kiel untenable, choose to withdraw their forces from there on

December 9th by retreating westward through Sehestedt, heading for more secure defensive positions around Rendsburg.

On December 10, 1813 the Danes found the English-German-Russian force strung out along the road leading from

Cluvensiek (German: Kluvensiek) through Sehestedt and further north. Surprisingly, having received no word from

the Swedes concerning by which direction the Danes were withdrawing and through failure of its own screening

cavalry to provide adequate intelligence, the Allied force was unaware of the Danish approach. Determined to reach

Rendsburg, the Danes chose to attack, took the town of Sehestedt by 10 o'clock in the morning, and were able to drive

the Allies back to their starting positions further south around Osterrade-Cluvensiek. The Danes continued to hold

Sehestedt through the day, allowing their force to continue its withdrawal. The engagement so unhinged the Allied

advance, that a cease-fire was called and agreed to, lasting into the new year, and peace negotiations were begun.

Military operations resumed on January 5, 1814, but within a few days another cease-fire was called, and negotiations

were taken up again. On January 16th a peace treaty was concluded at Kiel. Under the terms of the agreement, Denmark

lost control of Norway to Sweden, as well as having to make other concessions to the Allies.

Casualty figures for the Battle of Sehestedt vary, according to the source consulted. From the website of the "Arbeitskreis Hannoversche Militärgeschichte", two works will suffice. Bernhard Schwertfeger, Geschichte der Königlich Deutschen Legion 1803-1816, (Hannover, 1907; 1. Bd., p. 534-539) puts Allied losses at 42 officers, 1,129 enlisted men, of which more than 600 were prisoners; Danish losses were 17 officers, 531 enlisted men. Beamish, N. Ludlow, History of the King's German Legion, (London, 1832-37; v. 2, p. 199-218) states the matter differently: "The loss in this combat was considerable on both sides, but from the contradictory statements which have been put forward, it is difficult to offer an accurate estimate of it. A Danish account of the action exaggerates the loss of the allies to three thousand five hundred men, while it reduces that of the Danes to five hundred and forty-eight! It seems probably that the loss on each side was about one thousand. The allies lost also two guns, which fell into the enemy's hands on the charge of their cavalry, and the same number was captured from the Danes; but one of these was afterwards retaken."

In any event, and however many casualties, according to great-great grandfather Charles Prahl's testimony, his grandfather Johann Friedrich Andreas von Prahl, aka Sophus von Prahl, was among the Danish officers killed in action. The descrepency of date between Charles Prahl's account (1814), and the actual date (December 10, 1813) is minor. Certainly the information opens up the possibility of several additional avenues for research at a later time.

*****

THE SECOND DOCUMENT is the letter written by Emma Hagedorn, daughter of Adelaide Johanna Friedrike (Prahl) Hagedorn, the oldest child and daughter of Great-great-grandparents Charles and Friedrike (Storch) Prahl. The document is a typed letter, unsigned, 11" x 8 1/2", one side. On the letter are two manuscript notes that I believe to be in the handwriting of Mildred (Dickinson) England, daughter of Adelaide (Prahl) Dickinson, granddaughter of Charles and Friedrike Prahl. The copy I have is a xeroxed copy of the letter, slightly worn and illegible through several foldings through the years; the original has been lost. For a photocopy of the original, click here; for a transcription of the letter, click here.

Emma Hagedorn was just 68 years old (or "in her 69th year", as the Prahl family would say) when she wrote the letter. There are several items of interest in the letter, so I quote the relevent passages here:

"Miss Storch, Grandmother's sister, and my own great aunt, married a Doctor Berg. My Greatgrandfather, Charles Von Prahl, was head of the library of the Royal Family in that part of Germany, which at that period was under Danish rule, he directed the Royal School-book Library (Konigliche, Kaiserliche Schulbuchhandlung.) Grandma's Maiden name was Storch. The Storch's were a fine and well to do family."

"I used to hear my mother tell of a relative of the Storch family having been 'Lady-in-waiting' to the queen of Denmark."

One thing that has impressed me in doing family research is what information is remembered or not, and how often the remembered information becomes garbled, both in memory and in transmission. Emma Hagedorn's letter is a good case in point. First, the marriage of "Grandmother's sister, and my own great aunt" to a "Doctor Berg" was rather the marriage of her Grandfather Charles' sister, Johanna Sophia Friedrika Prahl, to Dr. Friedrich Meinroth Emil Berg in 1857. That the wedding was remembered indicates its significance to the family as a major social event. It also answers my own question that Charles Prahl continued to maintain some contact with his relatives left behind, as he and his family were already in New York. Of course, one of Friedrika (Storch) Prahl's sisters may have married *another* Doctor Berg, but I have not pursued the matter far enough to make such a determination. Second, Emma mentions that her great-grandfather Charles Von Prahl (Carl Friedrich Heinrich Prahl, b. 1802 in Rendsburg) was a librarian. This seems unlikely, as his occupation is listed consistently as "watchmaker". Of course, I have not accounted for any of his siblings, nor those of his wife Johanna Martha (Lundt) Prahl (b. 1804), nor those of the Storch ancestors. Certainly it is possible that one of them may have been a librarian, but I cannot determine it from the information presently in hand. Third, the same may be said for Emma's remark about a Storch relative being a lady-in-waiting for the Danish royal family.

Section E. The Schleswig-Holstein uprising of 1848 and the emigration of Charles Prahl and family to America

"Charles Prahl, who took part in the revolt above described, had to leave the Fatherland, and in 1853 he set sail for the United States, and upon his arrival in New York City he resided there for some time." -- Schlegel, v. 3, p 83.

And just how did great-great-grandfather Charles Prahl participate in these events, and why did his participation require him "to leave the Fatherland"? By itself alone, this sentence in Schlegel cited above has caused me much speculation. Truth to tell, though, I never really asked my grandfather Edward L.S. Prahl about it. Now that I cannot ask, and by the way the sentence is written, I might also wonder exactly how informative Charles Prahl himself was to his children and grandchildren about the events that led to his emigration. It would be certainly a fascinating story, for the 20th/21st century phrase that sums it all up is: "political refugee". Indeed, Charles Prahl is called such and is cited as being one of the "Forty-Eighters", that group of Germans who for their political beliefs and actions either left "the Fatherland" voluntarily after the failed uprisings and revolutions in Germany in 1848, or were compelled to leave by the governments that remained in power (The Forty-Eighters: political refugees of the German revolution of 1848 / edited by A.E. Zucker. New York, Russell & Russell, 1950: p. 327). Interestingly, Zucker cites Schlegel as the source for this information, and my own previously stated opinion is that my grandfather Edward L.S. Prahl is Schlegel's principal informant. One begins to see how circular the information becomes with everyone quoting one another, but not exactly backtracking to the source or doing more extensive research.