The history of sexuality has an intimate relationship with the Modern museum institution. I’m interested in the new and unusual ways sexual cultures and histories are represented in the museum and heritage industry today. One emerging form is the bordello or brothel museum. Venues for prostitution are opening their doors to a curious public, giving tours of the spaces where commercial sex took place and offering insight into histories and daily routines of sex work. Some bordello museums are defunct; others are active brothels offering varieties of visitor experience.

My previous object ethnography explored ‘negative-space heritage’ and visitor desire in Langtrees 181, an active bordello museum in Kalgoorlie, Australia. I tried to grasp the nature of the museum object by thinking through binaries of negative and positive space. Continuing to explore the interactions of materiality and visitor experience in erotic museum space, I want to open up the terms and possibilities to more nuanced shades of experience and location. Before, I looked at what wasn’t there; absent bodies and imagined exchanges in the museum as prostitutional cabinet. Here, I reconsider the nature of these spaces as social sites, exploring the contexts in which bodies and things, clustered in space, engage and perform together. Stepping back from the moment of visitor ‘artefact’ encounter, I offer some preliminary suggestions on how we might approach the brothel museum as a contestable, confusing and fascinating collective of stuff and folks.

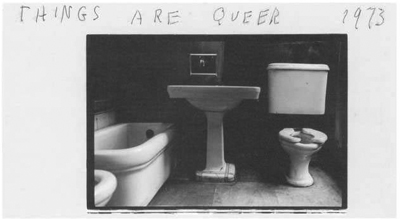

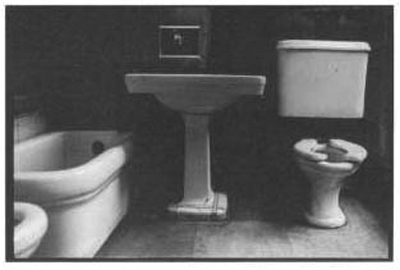

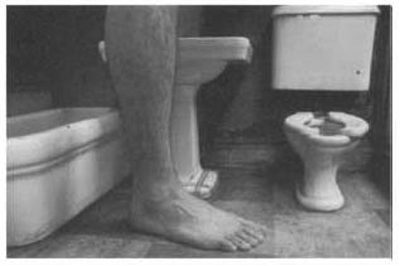

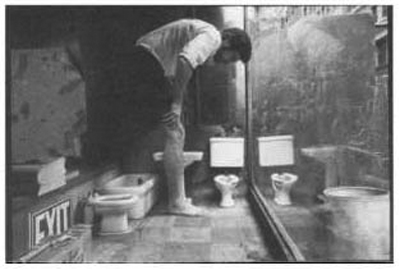

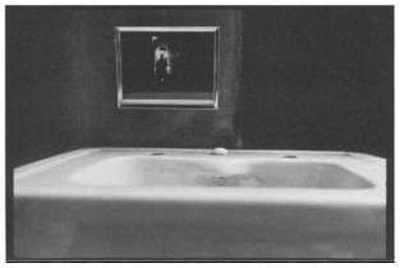

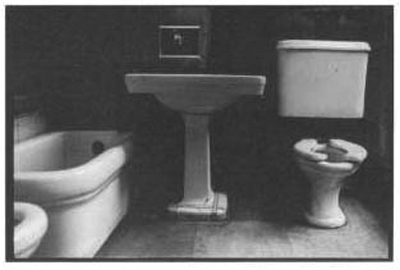

You might imagine how my interest was piqued when I came across the first image from Duane Michals’ 1973 series, titled ‘Things are Queer’. The image of a generic bathroom, with the words ‘Things are Queer’ handwritten on the print is the first of nine photographs. In the second image, a colossal hairy leg interrupts the bathroom space, but as the camera pans back we see that the giant’s leg belongs to an average proportioned man and the bathroom is small scale. The next image reveals that the photograph of the man in the miniature bathroom is an illustration in a book. As the camera retreats we see the book is being read by a man in a suit walking down a dark corridor, which is in fact, a reflection of the man in the corridor, caught in the mirror hung over the sink in the bathroom. The final image comes full circle, back to the bathroom where we began, however, our perception of the bathroom is considerably altered. Michals take the viewer on a disorientating journey, where space, time and narrative are confused and confounded. We could spend a long time piecing together the narrative of this series, but let’s linger a while in the immediate effect of disorientation, or in Gell’s terms, in our awed incomprehension. Art historian Jonathan Weinberg argues, “The queer of Things are Queer is not a matter of specific sexual identities but the world itself. The world is queer, because it is know only through representations that are fragmentary and in themselves queer. Their meanings are always relative, a matter of relationships and constructions. In contradiction to its title, the series seems to say that things themselves are not queer, rather what is queer is the certainty by which we label things normal and abnormal, decent and obscene, gay and straight.”[1] I agree that Michals’ work makes strange the confidence by which we comprehend and classify the real from its representation. In Weinberg’s usage, here the term queer refers to an oppositional position to dominant perceptions of the stability and fixity of ‘things’ and their categorizations. I disagree however, that the ‘things’ themselves are not queer. Things can be queer in queer spaces. And the men’s public bathroom is arguably the quintessential Modern queer space.

Michals’ work bears some comparisons with Tony Just’s untitled series of photographs of bathrooms from 1994. Photographing aspects of the space close-up - a basin tap, the curve of a toilet seat - Just register the spectres of gay public sex in a different era, after the terms of that culture changed dramatically because of the AIDS pandemic. Both of these Just and Michals invoke spaces claimed as arenas for possibilities restricted outside subterranean worlds. And each work shows, it is not just that homosexual acts take place in these spaces, but it is the material things in those spaces that bear much of the work of defining them as queer. In this example, the space of the bathroom site is embodied and materially specific; tiled walls, ceramic bowls, metal taps, the sounds of water, and the folks who interact with this stuff in ways particular to this space and to the object’s material affordances.

Configurations of things constitute spaces, and space is a thing in itself. The hole in a wall is as much of a thing as the solid matter of the wall; the hole-space is relational and contingent, but distinct. However, whether the wall is dyke, or the hole is a glory hole is significant; the affordances of form and their contexts matter. Commenting on the possibilities for a theory of queer space in the built environment, Christopher Reed asserts, “no space is totally queer or completely unqueerable, but some spaces are queerer than others.”[2]

I want to use the term queer here to do several things. Firstly, to consider the object of study obliquely from an oppositional position that seeks to make strange and denaturalise the status quo. This involves privileging ‘stuff’ and ‘folks’ generally marginalized in order to better understand the structures of that hierarchy.[3] And secondly, queer also draws our attention to non-normative sexualities; practices, behaviour, acts that are foils to, and yet positioned outside of, socially prescribed norms. Although I began with the bathroom, I want to think less about sexualities explicitly connected to gay, lesbian, bisexual or transperson communities, and focus on brothel economies. In queer studies the figure of the prostitute is often granted queer status as sex work is situated outside the boundaries of heteronormative propriety; it has certainly been sited beyond the walls of the museum.[4]

Queering the museum is an overdue project. One recent queer museum study on the Ellis Island Immigration Museum by Erica Rand, insists on seeing sex everywhere in order to problematize heteronormative assumptions of sexuality that museums create and perpetuate. Rand writes, “I aim in this book to dislodge the naturalness of sexual discretion and silence regarding Ellis Island, partly because sexual discretion and silence make possible presumptions of normativity. At issue here, too, more generally, are the challenges of getting at sex “in the flesh” from and through inanimate documents, artefacts and texts.”[5] Although Rand is not very symmetrical in her approach to humans and inanimate substance, her method is helpful. Firstly, it acknowledges the difficulty of apprehending configurations of stuff, folks and their history. How can we best understand the interaction of objects and people in the past, when the people are now gone, but the objects remain to interact with people in the present? The problematic of intangible and tangible exchanges between objects, memories and people, dead and alive, is a core concern. Secondly, thinking about ‘sex’ and ‘stuff’ heightens the demarcation between the human subject and material object. In a sexualised frame, the mind/body split become fuzzy, the body is at its most visceral and in contrast the object may appear inert. However, as Michals’ photographs demonstrate, considering the spaces that host corporeal/material encounters can reveal them to be symbiotic and most disorienting. The museum as a historical classification project of objects and humans is an excellent stage-space to consider these encounters.

In the final third of the twentieth century post-structuralist criticism primed a self-reflexive turn in museology.[6] The growing body of post-colonial critique compelled curators to examine the ethics of stewardship and display of collections compiled under colonialism. Through the lens of the ‘New Museology’ the museum institution was placed under critical scrutiny and considered not just an archive for conducting scholarly research in, but also a valid, indeed urgent, site to conduct research on.[7] Within this self-reflexive framework, the relationships between visitors, source communities and museum workers were given priority over museum collections. Museum theorists studied the contact and exchange between humans and objects were, so to speak, left on the shelf. The tendency of the new museology to feature socio-cultural relations at the expense of museum objects is beginning to be countered. Mary Bouquet advocates a Latourian approach to museum exhibitions and equalises the status of museum objects with that of visitors. She asserts, “The exhibition is both a collective (of humans and non-humans) and an event: tracing the trajectories of its component quasi-objects involves and intensely theoretical and at the same time intensely concrete set of practices.”[8] Conceiving of the museum as a collective transforms its terrain. Actor network theory is useful for thinking about the immersive quality of the museum performance and the scripts of the visitors and artefacts in dialogue with each other.

Let’s leave the bathroom and revisit the brothel. For the sake of brevity, I’ll take you on a whirlwind tour of some brothel museum spaces and then suggest two ways to think about them queerly. It’s important to note that I gleaned this scant information from museum and tourist websites, so in some ways this is a tour of a virtual network of brothel museums. I have faith that their real-life referents do exist, however the mediation of the internet inevitably impacts how I comprehend of the museums. The lack of physical access hinders a materialistic or phenomenological analysis of the museums; I have not experienced the wear of the stairwells underfoot or the sensation of being in the bedrooms. Accessing them only through trails of web pages shapes my impression of the museums as a constellation of sites.

------------>

------------>

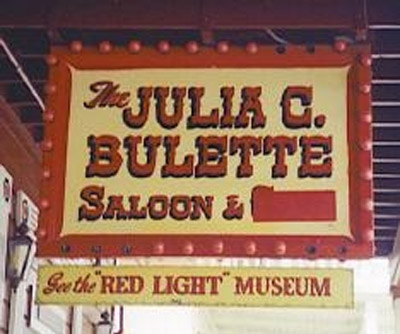

The ‘Red Light Museum’ in Virginia City, Nevada focuses on the 1860’s trade of local Madam Julia Bullette. The museum displays vintage erotica and antique medical equipment. Curiously, it also includes a diorama of Bullette’s murder. I couldn’t ascertain if the building itself was the former brothel. Nevada’s an interesting area because in some counties sex work laws are somewhat flexible. Working brothels have begun to style themselves as museums with tours as a way to advertise themselves on signs at side of highways.[9] Here however I wish to focus on historic-house museums.

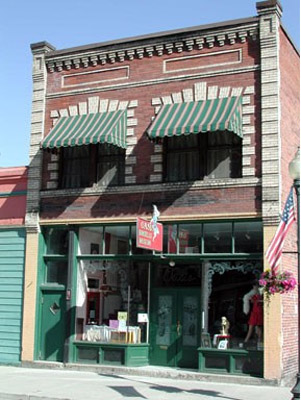

The ‘Oasis Bordello Museum’ in Idaho is a former brothel, which was still in business as recently as 1988. Apparently, the final occupants left in a hurry, leaving the upper rooms with their belongings as though they were going to return. I’m not sure if they have maintained the frozen scene, although it would not be surprising if they had re-created it; contemporary reconstructions that reify the past are common in the brothel museum.

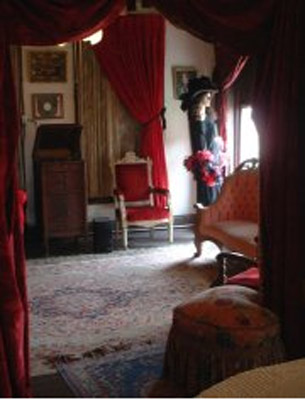

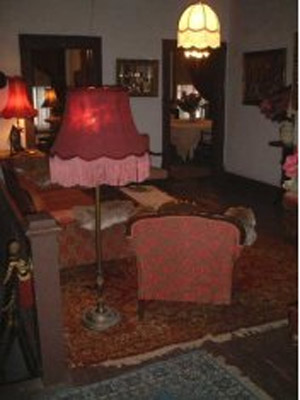

<-------->

<-------->

Left: Oasis Bordello Museum (Wallace, Idaho). Right: Old Homestead House Museum (Cripple Creek, Colorado)

Built and owned by Madam Pearl DeVere in 1896, the ‘Old Homestead House Museum’, Colorado sells itself as a high-class and highly haunted establishment. According to a tourist website, “Once in a while, according to staff, visitors will get a funny look on their face and suddenly ask if there are ghosts at the museum. Obviously, they are feeling a presence of something around them. During recent construction, there were several reports from workers who said that the former "girls" of the house were watching them work. Others have felt someone touching them and sensed movement out of the corner of their eye. Several people have reported that there are three former soiled doves who continue to reside at the old parlor house.”[10] The deaths of prostitutes, as well as ghostly presence, are reoccurring tropes. Admission to the ‘Old Homestead House Museum’ is half-price to children ages ten to thirteen and free for children under ten!

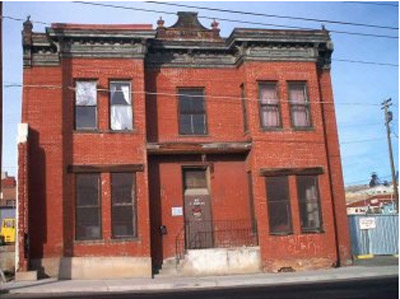

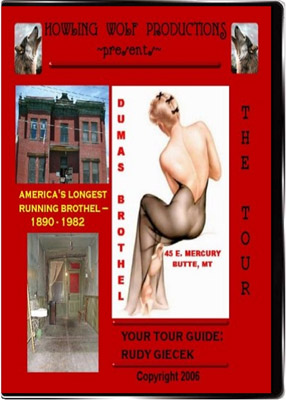

The Dumas Brothel in Butte Colorado was built in 1890 and active until 1982. In the early 1970s when it was still an active bordello the building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. No longer open, for tourists or for Jons, the Dumas is currently raising funds for restoration but there are books and t-shirts available on their elaborate website.[11] There’s also a large section devoted to dubious photographs which the proprietor claims capture of ghosts that haunt building.

------->

------->

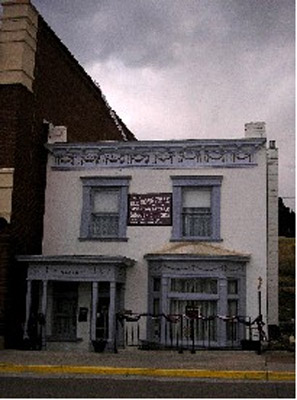

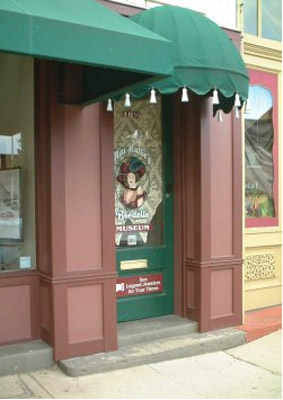

Open for tourist trade is Miss Hattie’s Bordello Museum, San Angelo, Texas. The bordello began in 1896 and was closed by the Texas Rangers in 1946. The history of the building is scarce. One story is that the parlor used to be connected with the original San Angelo National Bank building by a tunnel, so that while in town with their families, farmers and ranchers could discreetly visit the brothel under the auspices of doing their "banking" business.[12] The rooms shown to visitors today are a ‘restoration’, or reconstructions of how the space would have been at the turn of the century (minus the shop mannequin dressed in retro lingerie).

These brothel museums beg many questions not least about about authenticity, interpretation and heritage. Like other historic house attractions, there is an attempt to reify the past, and present it ‘as it was then’. But brothels are rather different from most historic houses. As extrajudicial places, the comings and goings of brothels are intentionally mystified. They are illicit and illusive spaces, banal no doubt for the workers, but shrouded in myth in the popular imagination. I’d like to offer two ways to think about brothel museums, firstly to grasp the knottiness of their social relations and secondly to understand how they situate and frame our understandings of the world and all the order of things within it.

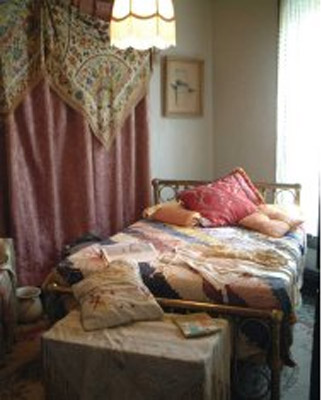

-->

--> -->

-->

Miss Hattie’s Bordello Museum (San Angelo, Texas)

-->

--> -->

-->

Anna Clark offers the metaphor of “Twilight” for sexual practice and desires prohibited by law or custom but which prevail nonetheless as a shaded or open secret. The metaphor is designed to accommodate complex social relations in the history of sexuality that may appear as contradictions; situations that are neither wholly deviant nor entirely compatible with the social norms. Twilight moments describes the temporal dimension of experiences that need not translate into fixed identities or permanent judgements of shame. In the 19th century, these moments may have involved married women in intimate relationships with other women, interracial sex, and husbands picking up street hustlers or frequenting bordellos. Sometimes, especially in periods of social stress such as war, economic depression or political instability, twilight moments exposed may have incurred strict social disciplining. At other times however, they could pass relatively freely. Clark shows people “indulged in these forbidden moments and then returned to their ordinary lives, just as twilight fades into darkest night and then night is succeeded by the dawn”.[13] Occasional acts or long-standing open secrets, complicit with or transgressive of the conventional social order, twilight moments help to complicate the subtle range of possibilities of how people conceived of their own and others' actions, at different points and places in history.

Clark’s metaphor of twilight may feel slightly resonant of 1950s pulpfiction romances, but I find it a useful way to think about how spaces, things, and people can shade in and out of different states, where identities, scripts, and outcomes are not fixed, bounded or perhaps even self-known. However, in addition to Clark’s concept of twilight moments and identities, I want to add twilight places.[14] By extending the metaphor to encompass places that host fleeting twilight moments we can consider these spaces as in some way part of the clandestine act. The 19th century brothel is certainly such a site; it not only facilitates, but also actively sculpts the human relations in the space. I also want to imagine twilight spaces as complex clusters of things and social relations, which can encompass historical contradictions, and which change their character over time, as different material affordances moving in and out of focus depending on the light. The 21st century brothel-museum is this type of twilight space; not quite in the real, yet not fully outside of it, the brothel-museum is a hybrid heterotopia.

In Of Other Spaces Foucault declares we are in an ‘epoch of space’. Foucault gives a brief history of space, from the hierarchies of the middle ages, the localization of the 17th century, to what he calls today’s ‘epoch of space’, characterised by a simultaneity between networks of connected sites. Although we have moved away from celestial hierarchies, Foucault argues that practically we have not de-sanctified space and there are some oppositions that remain sacrosanct “for example between private space and public space, between family space and social space, between cultural space and useful space, between the space of leisure and that of work. All these are still nurtured by the hidden presence of the sacred.”[15]

Sites connect with each other in networks or grids. What especially interests Foucault are sites that in some way obfuscate their relationships with other sites. The first of these kinds of spaces is utopias, an unreal perfect or inverted analogy of ‘real society’. The second, conversely, are heterotopias. Heterotopias are spaces between the real society and utopia, examples include prisons, gardens, cemeteries, hospitals, boarding schools and so on. Some of the key principles for these ‘other’ spaces are that they can stage relations that are ordinarily foreign to each other: “The heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible.”[16] They are often collapse diachronic temporality: “The heterotopia begins to function at full capacity when men arrive at a sort of absolute break with their traditional time.”[17] And accessing heterotopias is complex, as they are both isolated and penetrable: “Everyone can enter into these heterotopic sites, but in fact that is only an illusion: we think we enter where we are, by the very fact that we enter, excluded.”[18] The museum is presented as a heterotopia proper to the Modern epoch. The museum is “the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages, the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place.”[19]

Foucault recognises two types of heterotopia: heterotopias of illusion and heterotopias of compensation. I would venture the museum belongs to the latter; a real space committed to organised arrangements of things, compensating for a messy and disordered world. The heterotopic site of illusion in contrast, reveals the hope for an ordered world to be a chimera. The emblematic site for this heterotopia is the bordello. Foucault writes, “Their role is to create a space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory (perhaps that is the role that was played by those famous brothels of which we are now deprived.)”[20] Except here, Foucault is wrong. We are not deprived of these brothels, they’ve re-emerged, and they’ve been turned into museums! The illusory heterotopia of the bordello has become engulfed by the taxonomical project of the compensatory heterotopia of the museum. Things are very queer indeed.

Brothel-museums do what Michals' photographs do – they disorient our framings. They mix up categories of work, leisure, pleasure and vice that cultural heritage sites usually work hard to keep in their rightful place. I’m not suggesting that these museums are consciously progressive or subversive. The tales they spin of the colonial frontier, the cowboy, solider, miner and saloon girl, are very gendered, raced and sexed narratives of nation and citizenship that depend on unequal imperial power relations. On some levels, these sites are absolutely accepted and in line with conventional society; on other way, they are in a deviant and transgressive position. Switching the light on in these twilight places and turning the brothel into a museum shows us how queer things really are; the order of world is an illusion, however, chaos is being reclaimed by the museum time machine.[i]

bibliography

Boyce, David B., “Duane Michals: Photographer, Storyteller”, The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. Boston: Jan/Feb 2003. Vol. 10, Iss. 1; p. 28

Byrne, Denis. "Excavating Desire: Queer Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region." In Permanent Archive of Sexualities, Genders and Rights in Asia 1st International Conference of Asian Queer Studies Bangkok, Thailand, 2005.

Clark, Anna. "Twilight Moments." Journal of the History of Sexuality 14, no. 1/2 (2005): 139-60.

Cloud, John, “The Oldest Profession Gets a New Museum”, Time Magazine, (14 August, 2000)

Cohen, Cathy, “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” in Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology, ed. E.. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Henderson (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 21-51

Foucault, Michel. "Texts/Contexts: Of Other Spaces." Diacritics (1986): 22-27.

Kreps, Christina, Liberating Culture : Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Museums, Curation, and Heritage Preservation, Museum Meanings (London ; New York : Routledge 2003)

Rand, Erica. The Ellis Island Snow Globe. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

Reed, Christopher. "Imminent Domain: Queer Space in the Built Environment." Art Journal 55, no. 4, We're Here: Gay and Lesbian Presence in Art and Art History (1996): 64-70.

Vergo, Peter, ed. “The New Museology” (London: Reaktion Books Ltd1 1989)

Weinberg. "Things Are Queer." Art Journal 55, no. 4, We're Here: Gay and Lesbian Presence in Art and Art History (1996): 11-14.

websites

http://www.meganedwards.com/Vegasland/Pahrump-Brothels.htm

http://www.legendsofamerica.com/CP-Quirky.html#Prostitute%20Museum%20in%20Cripple%20Creek

http://www.thedumasbrothel.com/

http://www.waymarking.com/wm/details.aspx?f=1&guid=270099a0-c0df-4125-9d98-c51d4680be4f

[1] Weinberg, "Things Are Queer," Art Journal 55, no. 4, We're Here: Gay and Lesbian Presence in Art and Art History (1996). P11

[2] Christopher Reed, "Imminent Domain: Queer Space in the Built Environment," Art Journal 55, no. 4, We're Here: Gay and Lesbian Presence in Art and Art History (1996).

[3] I use the terms ‘stuff’ and ‘folks’ tentatively in an attempt to avoid hierarchical classifications. I like 'stuff' as a way to refer to material substances or items in plural that are not yet designated as objects or things; stuff can range from desk clutter to concrete slabs. I hope ‘folks’ may help avoid the connotations of liberal individualism and masculine gendering that ‘human’ can evoke. ‘Folks’ pluralizes and perhaps localises; associations of folklore and folk art inspire a socially embedded, egalitarian understanding of the humanness of people. I am conscious that it may also have connotations of heterosexual familial structures and maybe have political implications in terms of narratives of tradition and national identity, particularly in the United States. However, the UK TV series ‘Queer as Folk’ also helpfully contributes to its range of associations and illustrates that the usage of ‘folks’ that is not over-determined.

[4]See Cathy Cohen, “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” in Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology, ed. E.. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Henderson (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 21-51

[5] Erica Rand, The Ellis Island Snow Globe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005). p43

[6] For discussion see Christina Kreps, Liberating Culture : Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Museums, Curation, and Heritage Preservation, Museum Meanings (London ; New York : Routledge 2003) p6

[7] For example see Peter Vergo ed. The New Museology (London: Reaktion Books Ltd1 1989)

[8] Mary Bouquet, Thinking and Doing Otherwise: Anthropological Theory in Exhibitionary Practice, in Museum Studies: an Anthology of Contexts, op.cit., pp193-207, p203

[11] http://www.thedumasbrothel.com/ and John Cloud, “The Oldest Profession Gets a New Museum”, Time Magazine, (14 August, 2000)

[12] http://www.waymarking.com/wm/details.aspx?f=1&guid=270099a0-c0df-4125-9d98-c51d4680be4f

[13] Anna Clark, "Twilight Moments," Journal of the History of Sexuality 14, no. 1/2 (2005).

[14] Clark briefly mentions alternative zones in the city conducive to unconventional sex practices but doesn’t explore this area.

[15] Michel Foucault, "Texts/Contexts: Of Other Spaces," Diacritics (1986). p23

[16] Ibid. p25

[17] Ibid. p26

[18] Ibid. p26

[19] Ibid. p26

[20] Ibid. p 27

[i] My next step would be to consider what happens to the things clustered in these spaces, as this transference or hybridization between brothel and museum/heritage site takes place. In an exploration of queer heritage sites Denis Byrne looks at spaces that have been claimed and used by glbt communities over time and which have taken on a physical and symbolically queer character. Byrne bemoans the conservation of queer heritage sites as it de-eroticizes the histories that animate it. He writes “the landscape we encounter in the present is already meaningfully constituted and that, in a sense, it speaks to us. In our case, the lived experience of homosexuals who existed in these places in the past – their activities, their love etc. has sedimented itself into physical being of the places. The places are thus not inert.”[i] For Byrne eroticism and experiences linger in a place and accumulate on the material there. How can the material forms of a site accumulate erotic experiences? Do things acquire a queer patina? Does that patina wear away under the museum gaze? The convergence of queer theory and thing theory is extremely fertile for struggling to think about the cultural history of sexuality through museums of sex. Unlike Duane Michals, I’m not suggesting that all things are queer, but some are, in some spaces and at certain times, especially at twilight.