Development Mini-Didactics

Return to Development Intro Page

- Infant Colic

- Sleep advice

- Night Terrors

- Newborn Reflexes

- Development of the Reach

- Development of the Grasp

- Emergence of Handedness

- Screening for Dyslexia

- Toilet Training

- Mental Retardation

- Cerebral Palsy

- Intoeing (word document)

Infant colic - Rule of 3’s: unexpected episodes of crying lasting more than 3 hours a day, more than 3 days in a week, for more than 3 weeks

- A pattern of crying more intense and frequent than usual

- Usually starts in the 2nd week and resolves at the end of the 3rd month

- Typically occurs in late afternoon or early evening

- Duration of normal daily crying peeks at 6 weeks

- Seen in all cultures, unknown etiology, perhaps GI distress or immature neurologic development combined with infant’s temperament

In the office: - observe a feeding for technique, especially bottle position to avoid swallowing air

- review mixing of formula and approximate 24 hr volume of feeds (about 1 oz /hr is appropriate)

- review burping frequency and technique

- can consider food intolerance as possible etiology (milk protein, foods/chemicals in breast milk)

What to Do: Dr. Harvey Karp’s Method (The 5 S’s):

• Swaddle tightly

• Side/stomach position - place the baby, while holding her, either on her left side to assist in digestion, or on her stomach. Once baby is asleep, she can be put safely in her crib, on her back.

• Shushing Sounds - Or white noise in the form of a vacuum cleaner, a hair dryer, etc may also help.

• Swinging

• Sucking - This "S" can be accomplished with bottle, breast, pacifier or even a finger. Help hold the pacifier in the baby’s mouth if baby drops it. (At a young age, babies tend to lose pacifier involuntarily.) Also, let parents know it is okay to take a break! It is very stressful to have a colicky baby, and it is okay to put a crying baby down and step out of the room to take some quiet time. This reduces the chance that a parent will getoverwhelmed and do something to hurt the baby. Help parents understand that although crying indicates distress, it does not necessarily mean that the baby is in danger. Parent Resources

Good Sleeping Habits for Baby

(These tips are for after 3-4 months; cannot train before then. Follow baby’s lead on sleeping/eating for first 3 months) Finish the feeding before putting the baby downLet the baby fall asleep in the crib, not in your arms. This may help the baby fall back to sleep without parent’s presence during normal night awakeningsBe as consistent as possible with sleep times and places. Start a routineDon’t respond to baby’s every whimper at night. Give her a chance to settle back down on her ownMake evenings calm and relaxing Parent Resource: Sleep Tips

Night Terrors - sleep disturbance that may resemble nightmares but with a more dramatic presentation

- much more rare than nightmares: about 3-6% of children have night terrors, whereas almost every child has nightmares (esp. ages 3-6)

- occurs during first 2-3 hours of sleep, during deep non-REM sleep

- usually described as child sitting upright in bed, screaming, and appearing confused or afraid

- children are not able to be comforted during the night terror

- children do not remember night terrors in the morning; it is not a dream, and there are no images created to remember

- they may be more prevalent in kids who: are overtired or ill, stressed or fatigued, taking a new medication, or sleeping in a new environment or away from home

Tips for Parents: - If a child has a night terror, it is best not to try to wake them up

- To prevent night terrors, reduce child’s stress

- Establish and stick to a bedtime routine that’s simple and relaxing

- Make sure the child gets enough rest

- Prevent the child from becoming overtired by staying up too late

Web Resource/Parent Handout: Night terrors (English)

Night terrors (Spanish)

Newborn Reflexes

Note: Primitive reflexes must disappear before voluntary behavior appears. For example, the grasp reflexes must be gone before voluntary grasp begins. Moro Reflex

Also called the startle reflex, the moro is usually triggered if the baby is startled by a loud noise or if his head falls backward or quickly changes position. The baby's response to the moro will include spreading his arms and legs out widely and extending his neck. He will then quickly bring his arms back together and cry. The moro reflex is usually present at birth and disappears by 3-6 months. Grasp

This reflex is shown by placing your finger or an object into your baby's open palm, which will cause a reflex grasp or grip. If you try to pull away, the grip will get even stronger. In addition to the palmar grasp, there is also a plantar grasp, which is elicited by stroking the bottom of his foot, which will cause it to flex and his toes to curl. The palmar and plantar grasp usually disappear by 5-6 months and 9-12 months respectively. Tonic Neck Reflex

A postural reaction, the asymmetric tonic neck reflex, or fencer response, is present at birth. To elicit this reflex, while a baby is lying on his back, turn his head to one side, which should cause the arm and leg on the side that he is looking toward to extend or straighten, while his other arm and leg will flex. This reflex usually disappears by 4-9 months.

Stepping/Walking

If you hold a baby under his arms, support his head, and allow his feet to touch a flat surface, he will appear to take steps and walk. This reflex usually disappears by 2-3 months, until it reappears as he learns to walk at around 10-15 months. Positive Support Reflex

Like the stepping reflex, if you hold a baby under his arms, support his head, and allow his feet to bounce on a flat surface, he will extend (straighten) his legs for about 20-30 seconds to support himself, before he flexes his legs again and goes to a sitting position. This reflex usually disappears by 2-4 months, until it becomes a more mature reflex in which there is a sustained extension of the legs and support of his body by about 6 months.

Development of the Reach - Closed hand reaching: 2-3 months

- Hands open with reach: 4 months

- Accurate reaching: 6 months

- Anticipatory hand shape and movement: 9 months

- Coordinated timing of hand closure with reach: 13 months

Development of the Grasp

Emergence of Handedness:

Parent resource: http://www.drspock.com/article/0,1510,5814,00.html - Any motor asymmetry in first 6-9 months of life likely indicates nervous system damage

- Although this is unusual, by as early as 6-9 months, you may see very subtle signs of dominance with careful observation. However, keep in mind that this is unusual and for the most part, no dominance is seen until about 18 months of age.

- Dominant hand becomes more and more apparent in ages 1-3.

- Clear and consistent handedness is not established until 4-6 years of age. About 15-18% of children will still not have established clear dominance of one hand by school entry.

- Mixed dominance is seen in a greater proportion of children than adults, which suggests that there is a continuum of increasing lateralization with age.

- A strong genetic predisposition to dominance exists. Only 2% of children of right-handed parents are left-handed, whereas 42% of children with left-handed parents are left-handed.

Screening for Dyslexia Tests you can do in your office: - Letter Identification (naming letters of the alphabet)

- Letter-sound association (e.g. identifying words that begin with the same letter from a list: doll, dog, boat)

- Phonologic awareness (e.g. identifying the word that would remain if a particular sound was removed: if the /k/ sound was taken away from “cat”)

- Verbal memory (e.g. recalling a sentence or a story that was just told)

- Rapid naming (rapidly naming a continuous series of familiar objects, digits, letters, or colors)

- Expressive vocabulary, or word retrieval (e.g. naming single pictured objects)

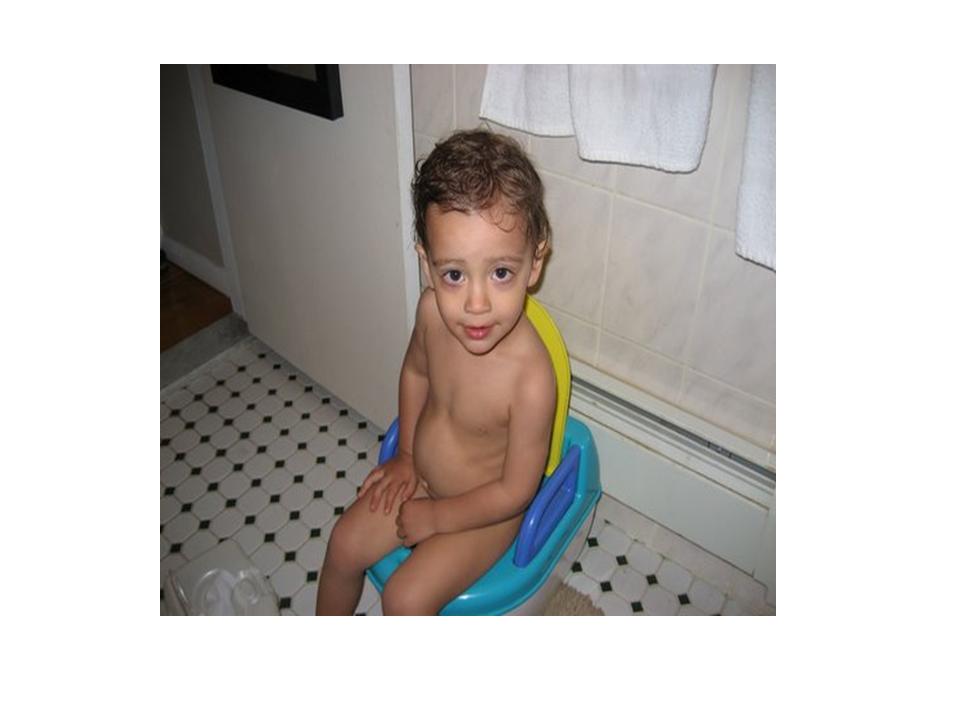

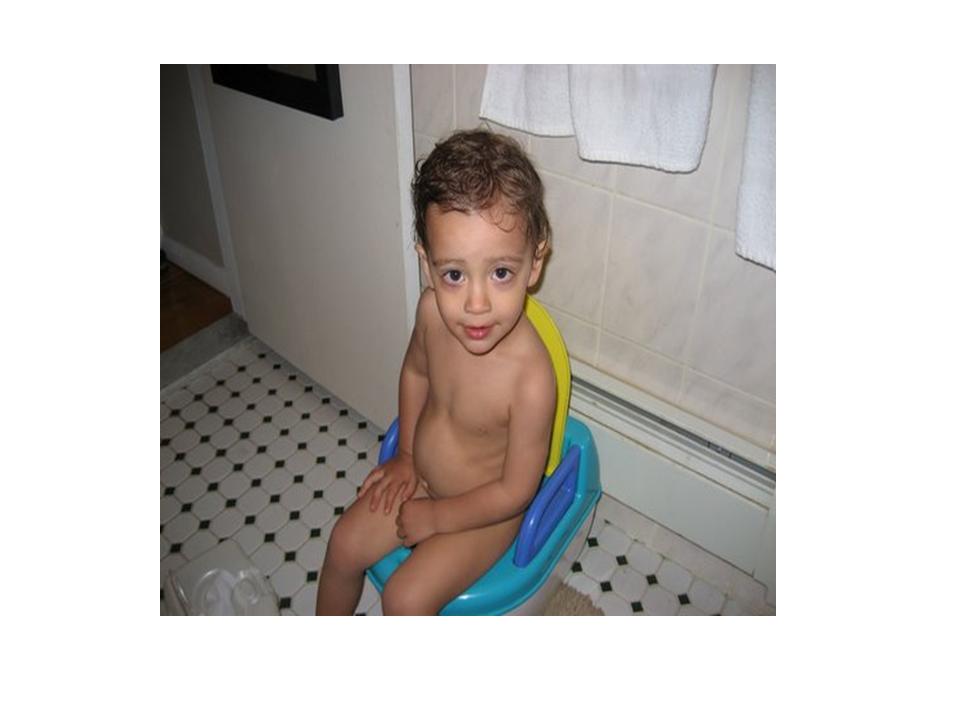

Toilet Training

A child centered approach (see Brazelton model below) - May begin around age 24-30 mos. Most can be trained by around 36 mos so the earlier one starts, the longer time will be spent, with potential for frustration and anxiety

- Relatively easy skill for children to acquire if parents wait for child to be ready

When is the child ready? - can walk and sit down backwards on a chair

- can pull down his own clothes

- can signal that he needs to use the potty.

- has increased periods of daytime dryness

- shows interest in the toilet

How to start toilet training:- Introduce a potty seat on the floor, to be used in bathroom, kitchen, bedroom or on outings

- Take child into the bathroom and demonstrate the process

- Dump diaper contents into potty then toilet

- Having the child sit on a potty chair (even with diaper on) is a first step

- The parent should be positive. Never rush or get upset

- Practice and encouragement are key. The parent should observe the child’s routine and give praise. Pleasing the parent and the ability to use the potty independently are the child’s rewards

- Never force the child to stay on the potty

- If the child resists, discontinue training for 2-3 months

Continuation of toilet training: - Remember the process will be learned by 3-3.5 yrs regardless of when you start

- Avoid excessive praise or punishment; may be perceived as pressure to the child.

- Expect regressions with illness, vacations, or changes in family situation. Remain positive and preserve the child’s self-respect during these times.

- Wearing diapers at night is normal; not considered enuresis until after age 5-6.

- The fear of the toileting experience is common

The Brazelton model – a child-oriented model developed in the 1960s. It is the standard of practice for most pediatricians now. It states that toileting behavior emerges not only from physiologic attainment of bladder and bowel control in a child but also when a child develops sufficient neurologic maturity to voluntarily accept the responsibility to participate in toilet training. This model spoke against the previously used absolute rules for toilet training with the idea that rushed, rigid training may fail and may even cause behavioral problems, like urinary and fecal withholding. Parent Handout: (Spanish) (English) Resources: - Brazelton, T. Berry et al. , Instruction, Timeliness, and Medical Influences Affecting Toilet Training. Pediatrics. Vol. 103 No. 6 Supplement June 1999, pp. 1353-1358

- http://www.aap.org/healthtopics/toilettraining.cfm

- UP TO DATE FILE

Mental Retardation (MR) occurs in approx. 1-3% of the general population. MR is mild in approximately 85 percent of affected individuals.

Diagnostic criteria for MR

An IQ of 70 or below, as measured by an age-appropriate individually administered IQ test.

Normal IQ is 2 standard deviations above and below the mean, with a mean IQ being 100. Degrees of MR and corresponding IQ scores are: mild, 70-55; moderate, 55-40; severe 40-25; and profound, less than 25.

Deficits in adaptive functioning in at least 2 of the following areas: communication, self-care, home living, social/interpersonal skills, use of community resources, self-direction, functional academic skills, work, leisure, health, and safety.

Onset of symptoms before 18 years of age.

Etiology of MR: The causes of MR are extensive and include any disorder that interferes with brain development. A cause can usually be identified in approx 1/3 of children who have MR. Autism must be considered in the ddx of MR Prenatal

Cytogenetic abnormalities like Fragile X syndrome (in 1-2% of people with MR), Down Syndrome (most common form of inherited MR), etc.

CNS malformations

Placental insufficiency (intrauterine growth restriction)

Congenital infection (Toxo, CMV, HSV, Rubella, etc)

Environmental toxins or teratogens (eg, alcohol, lead, mercury, hydantoin, valproate) – can also occur postnatally

Congenital hypothyroidism

Perinatal

Infection

Trauma

Intracranial hemorrhage

Postnatal

Accidental or non-accidental trauma

Hypoxia (near-drowning) Environmental toxins

Psychosocial deprivation

Malnutrition

Intracranial processes such as infection, CNS malignancy, hemorrhage

Initial Presentation:

Language delay, immature behavior, or immature self-help skills

Language development is considered a reasonably good indicator of future intelligence in a child without hearing impairment. Thus, language delay associated with global developmental delay suggests cognitive impairment.

Evaluation

Complete history and physical examination, including head circumference at each visit

Vision and auditory screening

Karyotype and fragile X testing

The following studies should be performed for specific indications:

Metabolic studies (serum amino acids, urine organic acids, serum ammonia, and lactate) and thyroid screen (T4, TSH) if newborn screen not available or if clinical signs suggest a metabolic disorder or hypothyroidism.

EEG in a child with seizures or a suspected epilepsy syndrome

Perform a karyotype in all children and perform cytogenetic testing if there is a family history of developmental delay or characteristic physical findings.

If H&P suggests CNS malformation or injury, obtain imaging (preferably MRI)

If risk factors are present for environmental exposure to lead, obtain a lead screen; testing for lead should be considered in all mouthing, delayed children

Management:

Early diagnosis and intervention, as well as access to health care and educational resources

Speech and language therapy

Occupational and Physical therapy and rehabilitation including mobility and postural support

Family counseling and support

Behavioral intervention

Educational assistance, i.e. smaller class special education system in NYC

MR pearls:

Individuals with mild MR usually achieve a 3rd to 6th grade reading level and often can live and work independently. Many marry and parent children. In contrast, individuals with moderate MR usually attain a 1st to 3rd grade reading level, live in homes with support, and work with supervision.

MR reflects developmental age in such a way that child's emotional age reflects their mental age so when evaluating behavior in a child with MR, one must think in the context of mental age not chronological age

References: 1. http://www.utdol.com/utd/content/topic.do?topicKey=ped_neur/17778&selectedTitle=3~209&source=search_result

2. Walker, William Otis et al. Mental Retardation, Overview and Diagnosis. Pediatrics in Review. 2006;27:204-212

Cerebral Palsy

Definition – a static encephalopathy with following characteristics:

1) motor impairment syndrome

2) nonprogressive brain lesion

3) injury occurred to the brain before it was fully mature Prevalence and Risk Factors

CP affects 2-3 per 1000 children in the US. Although it may be difficult to determine the exact cause of the motor impairment for an individual child, several clinical conditions are associated with an increased risk of CP, including brain malformation, chromosomal abnormalities, IUGR, prematurity, birth hypoxia, and postnatal events such as traumatic injury and meningitis. Classification

CP may be classified physiologically into pyramidal or extrapyramidal. Pyramidal CP is also known commonly as spastic CP, and extrapyramidal is sometimes called dyskinetic CP. About 65% of CP is spastic, 25% is extrapyramidal, and 10% is mixed.

Features distinguishing Spastic vs. Extrapyramidal CP

| | Spastic

| Extrapyramidal

| Hypertonicity

| Velocity dependent

| Velocity independent

| Deep Tendon Reflexes

| Increased

| Normal to decreased

| Contractures

| Common

| Uncommon

| Movement Disorder

| None

| Choreoathetosis, dystonia, ataxia may be seen

| Sleep

| Unaffected

| Decreases tone; movement disorder is eliminated

|

CP may also be classified topographically (hemiplegia, diplegia, quadriplegia, double hemiplegia, monoplegia, triplegia). Because children with extrapyramidal CP usually have involvement of all 4 limbs, the topographic classification is used primarily for pyramidal CP. - Hemiplegia - one-sided involvement, upper extremity more involved than lower.

- Diplegia - primary involvement of the lower extremeties.

- Quadriplegia - four extremity involvement, lower extremities more involved

- Double hemiplegia - four extremity involvement, upper extremities more involved

Diagnosis

Any infant with delayed motor development must be considered suspect for having CP. Diagnosis is very difficult before 6 months of age, primarily because abnormalities in tone or reflexes rarely manifest in early infancy. Much of the movement observed in infants younger than a few months of age is of reflex origin and not under voluntary motor cortical control. With maturation of the brain cortex, the clinical picture of CP emerges more clearly. A number of clues raise the index of suspicion for CP, and these high-risk findings can be assessed easily during a routine well-child examination. (See the Cerebral Palsy Screening Tool). Tone, primitive reflexes, and deep tendon reflexes are the mainstay of the exam.

Management

If a diagnosis of CP is suspected, enrollment in an early intervention program will provide family support for coping, parental education for handling a child at home, and treatment to promote motor and other developmental skills of the child. The long-range management addresses both motor dysfunction and associated non-motor deficits.

LINK to Early intervention Referral Form

Prognosis

In predicting long-range outcomes, one must consider many different variables, including physical capability, intellectual capability, and psychosocial adjustment. Generally speaking, children with hemiparesis walk by 1.5 to 3 years of age. 80-90% of children with diplegia, 70% of those with dyskinesia, and 50% of those with quadriparesis attain some mode of ambulation. In these clinical types, the ability to sit independently by 1.5 -2 years offers a good prognosis for community ambulation. Children who learn to sit at 2-4 years usually become household ambulators, and some may walk short distances outdoors with assistive devices. Walking is not expected of children who cannot sit by 4 years of age.

Achievements in daily living skills are consistent with intellectual competence, regardless of the degree of physical disability.

|