FWP:

SETS == EK; HERE/THERE; MUSHAIRAH

ZARRAH: {15,12}

This is the kind of verse that I've called a 'mushairah verse'; for more on this see {14,9}. The first line is opaque without the second; the second defers gratification till the very end, and then delivers one good big punch. After you've enjoyed that, you're ready to go on to the next verse; you don't keep on thinking and thinking about it.

Here, as is often the case with such verses, the pleasure is in unexpected wordplay. The whole occasion is 'hot', of course, as Nazm points out, but that's just the foundation. It's the juxtaposition of the prosaic, practical, commonplace act of 'binding on' a litter to a camel's back for travel, and the impossibly extravagant, futile, crazy absurdity of 'binding on' a heart to every sand-grain in the vicinity (or in the whole desert), that can't help but be amusing. There is a Persian idiom, dil bastan bah chiize , 'to bind one's heart upon a thing' (Steingass p. 531), that Ghalib is literally translating.

The evocation of a 'binding on' activity as performed-- how differently, in such different situations!-- by both beloved and lover, makes this a kind of 'here/there' verse; for more on these, see {15,2}.

This verse also performs the clever negative feat of avoiding in both lines something that the audience would certainly be expecting: the literary sense of baa;Ndhnaa as 'to compose (a verse)'; for more on this sense, see the next verse, {29,2}. Out of the four divan verses in this ghazal, only this opening-verse-- the only one that must use the refrain twice-- wittily and perversely refuses to introduce this hovering (and strongly inviting) sense of the term.

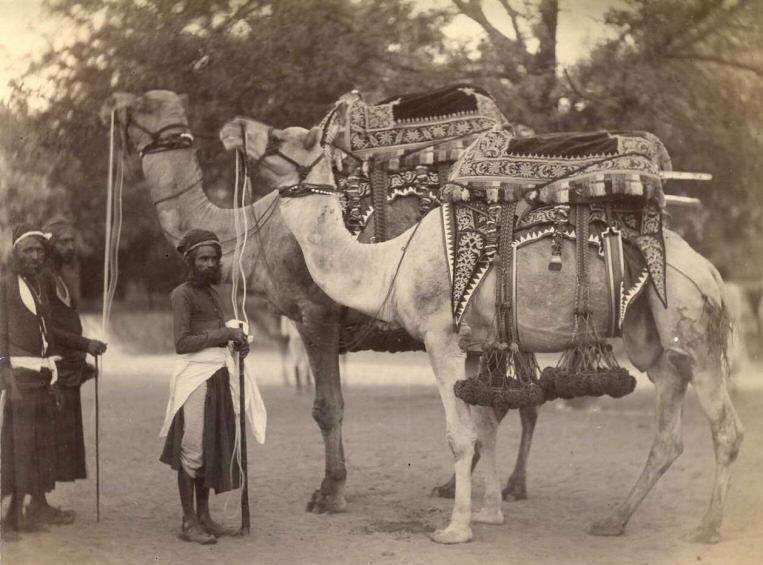

Note for the literal-minded: A male beloved might possibly 'bind on', we might imagine, a camel-saddle like the elaborate ceremonial ones depicted in this photo (late 1800's):

For a female beloved, however, the case would be different; see {147,7x} for further discussion of the nature of a ma;hmil . For other ma;hmil baa;Ndhnaa verses, see {259x,1}; {352x,1}.

Nazm:

In the burning of the sand-grains and the heat of the heart, the cause for similitude is clear. (29)

== Nazm page 29