Japan met the West in 1853. On July 8, two frigates and two vessels directed by the U.S. Navy Commander Mathew Perry entered the harbor of Uraga. Perry's mission was to convince the Japanese government to establish diplomatic and commercial relations with the United States, thus ending a two-centuries-long policy of isolation. With the treaty of Kanagawa signed on March 31, 1854, Japan agreed to open its ports to foreign trade. Article 7 of the treaty reads:

It is agreed that ships of the United States resorting to the ports open to them shall be permitted to exchange gold and silver coin and articles of goods for other articles of goods, under such regulations as shall be temporarily established by the Japanese Government for that purpose. It is stipulated, however, that the ships of the United States shall be permitted to carry away whatever articles they are unwilling to exchange.

Similar treaties were signed with other Western countries in the years that followed.

A new craze for all things Japanese soon invaded the West, especially Britain, France, and the Netherlands. Japanese handicrafts and art objects were the rage of the day. Fans, kimonos, antiques, lacquer boxes, bronzes, prints could be admired at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867, as well as purchased in the most stylish shops in town. The appeal of Japan profoundly influenced artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Toulouse-Lautrec and Edgar Degas. In La Japonaise, Monet painted his wife Camille wearing a red kimono and holding a fan in her hand. The term "Japonisme" was coined by the French art critic Philippe Burty in 1876 to describe this new Occidental fascination with Japan.

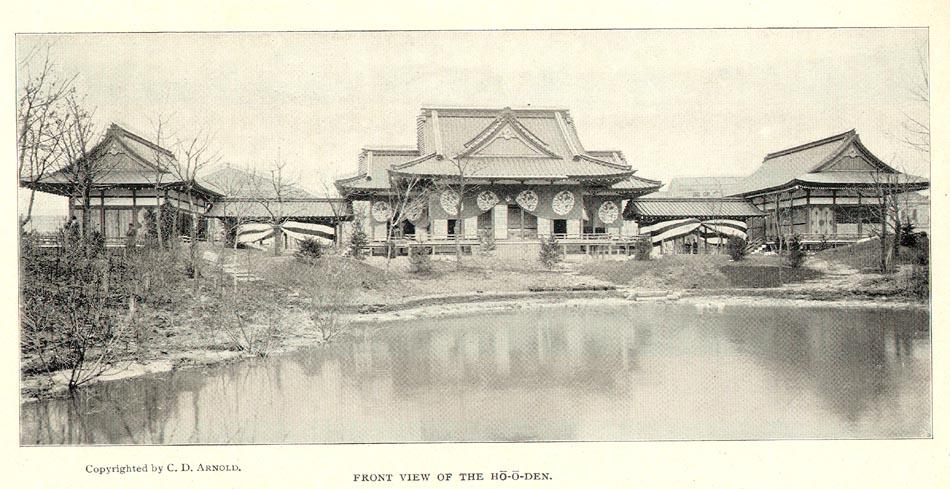

In that same year, the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition featured a Japanese Pavilion. It was the first sign of a rising interest in Japan that, as in Europe, would influence American cultural life well into the 20th century. The exotic lure of the East captivated millions of visitors at the 1893 Columbian World's Fair in Chicago. One of the most admired buildings was the Japanese Ho-o-den (built on the Wooded Island), a large compound showcasing different examples of 12th-, 16th-, and 18th-century Japanese architectural styles. The exhibition profoundly influenced, among others, the famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

As Americans decorated their houses with Japanese-inspired furniture and objects, a whole new sub-genre of Japanese fiction flourished in the American literary markets of the last two decades of the 19th century. Among the most successful exponents of this trend were William Elliot Griffis (The Mikado Empire, 1880), Basil Hall Chamberlain (Things Japanese, 1905) and John Luther Long, whose short novel Madame Butterfly (1898) would provide the story for the libretto of Puccini's Madama Butterfly.

The tragedy of Cho-Cho-San has raised many questions. Was her story entirely fictional? Long would seem to have heard the story of the poor tea-house girl abandoned by her Western lover from his sister Jennie, who was the wife of a Methodist Episcopal missionary in Japan. In 1931, she gave a series of talks (later published in The Japan Magazine) on the "real" Madame Butterfly:

On the hill opposite ours lived a little tea-house girl; her name was Chô-san, Miss Butterfly. She was so sweet and delicate that everybody was in love with her. In time we learned that she had a lover. That was not so strange, for all tea-house girls have lovers, if they can get and hold them. Chô-san's young man was quite nice, but very temperamental, of a moody, lonely disposition. One evening there was quite a sensation when it was learned that poor little Chô-san and her baby, had been deserted. The man promised to return at a certain time; had even arranged a signal so that Chô-san would know when his ship had come in; but the little girl-wife awaited that signal in vain. ... He never returned.

"Temporary wives" were a sad reality in Japanese treaty ports at the end of the 19th century. The practice seems to have been quite widespread. Fact and fiction might indeed have merged in the emblematic figure Cho-Cho-san.

Puccini saw a theatrical adaptation by the American actor and playwright David Belasco of Long's novel in London, in June 1900. It was love at first sight. Back in Italy, he immediately communicated to the publisher Giulio Ricordi his intention to write an opera on the subject of Madame Butterfly. It is hard to tell to what extent Puccini was aware of the historical circumstances that surrounded the heroine of his opera. In his correspondence he mentions that Mrs. Oyama, the wife of the Japanese ambassador to Rome, told him that she "knew a story roughly like that of Butterfly that really happened." The story of Madame Butterfly seems to have rapidly transformed itself into an archetypical myth of the encounter between Japan and the West.

Puccini's music embodies the same mixture of reality and fiction. Imaginary musical reconstructions of Japan and quotes from authentic Japanese music coexist in the score. Puccini took great pains to recreate the "realistic" musical atmosphere of Japan. Mrs. Oyama was his main informant in Italy:

She told me so many interesting things, sang me some native songs and promised to send me some music from her country.

He copied and studied melodies from publications that contained transcriptions of Japanese songs. It would seem that he was also able to listen to records shipped from Tokyo. Puccini uses these melodies to underscore what he saw as key aspects of Japanese culture, but also to characterize musically the protagonists of the opera. Thus, the wedding between Pinkerton and Cho-Cho-San is accompanied by the Japanese national anthem Kimi ga yo. According to the scholar Kimiyo Powils-Okano, at least ten authentic melodies can be identified in Puccini's score. But Puccini also invented his own sonic image of Japan. A distinctive feature of this imagined Orient is the use of pentatonic and whole-tone scales, which Western musicians of this period tended to associate with a rather broadly defined and exotic East.

In Madama Butterfly the West, too, is musically depicted in a realistically evocative fashion. Pinkerton sings his first aria ("Dovunque al mondo" ... -- "All over the world the Yankee vagabond ...") on the notes of "The Star Spangled Banner" (which at that time was the Navy anthem, before it became the National Anthem in 1931). But also the frantic imitative texture of the prelude seems to allude, from the very beginning of the opera, to the presence of the West through the busy machinery of counterpoint. In the context of such a musically strong characterization of the West, Cho-Cho-San's music (whether or not based on authentic Japanese music) seems to project the image of an infantilized world, epitomized in the delicate and fragile musical idiom of the infantilized heroine of Puccini's opera, Cho-Cho-San, the girl-bride, "bimba dagli occhi pieni di malia" ("a child with eyes full of seduction").

Giuseppe Gerbino

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Girardi, Michele: Puccini: His International Art (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000).

Groos, Arthur: "Madama Butterfly: The Story," Cambridge Opera Journal 3/1 (1991): 125-58.

Powils-Okano, Kimiyo: Puccinis Madama Butterfly (Bonn: Verlag f�r systematische Musikwissenschaft, 1986).

van Rij, Jan: Madame Butterfly: Japonisme, Puccini, and the Search for the Real Cho-Cho-San (Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2001).