Looe : A Finish

TODAY'S ITINERARY

Exploration: Monday, 21 October, 2019

lv London Paddington 0635 Great Western Railway

ar Plymouth 0934

lv Plymouth ~1032 Great Western Railway

ar Saltash 1041

lv Saltash 1057 Great Western Railway

ar Liskeard 1116

lv Liskeard ~1214 Great Western Railway

ar Looe ~1245

lv Looe 1458 Great Western Railway

ar Coombe Junction Halt 1522

lv Liskeard ~1732 Great Western Railway

ar London Paddington 2122

(The timetable changed by the time I wrote this page, so I had to reconstruct a few timings shown by the ~ symbol. On the Great Western in particular the timings have been much improved because of new trains that run faster. On the October journeys I noticed we had to stand for five minutes or longer at some stations because we came in too soon on a schedule made for the slightly older equipment.)

It's very important to make my flight back to the USA, so several times I preferred to stay near London the day before I leave. I have to admit I broke my rule in 2018 by taking Eurostar to Paris and back the day before departure. The worst part is that I got away with it.

Following that questionable example, on this last full day I decided to go all the way to Cornwall.

The journey started at Paddington, once more on the 0635 departure that has taken me to Exeter and onward a few times now. There are always plenty of seats available, all with the thoughtful provision of a tray on the seat back. By habit I secured the black coffee and a couple of excellent croissants at the station and settled in for quite a long journey this time, to Plymouth, three hours out of London.

Publicity featuring Paddington Bear has taken firm hold in the station. The statue of the bear that was once on The Lawn is, last I saw it, on platform 1 near the eventual entrance to the Crossrail or Elizabeth Line station below. Great Western Railway has an Intercity Express train named for the bear too.

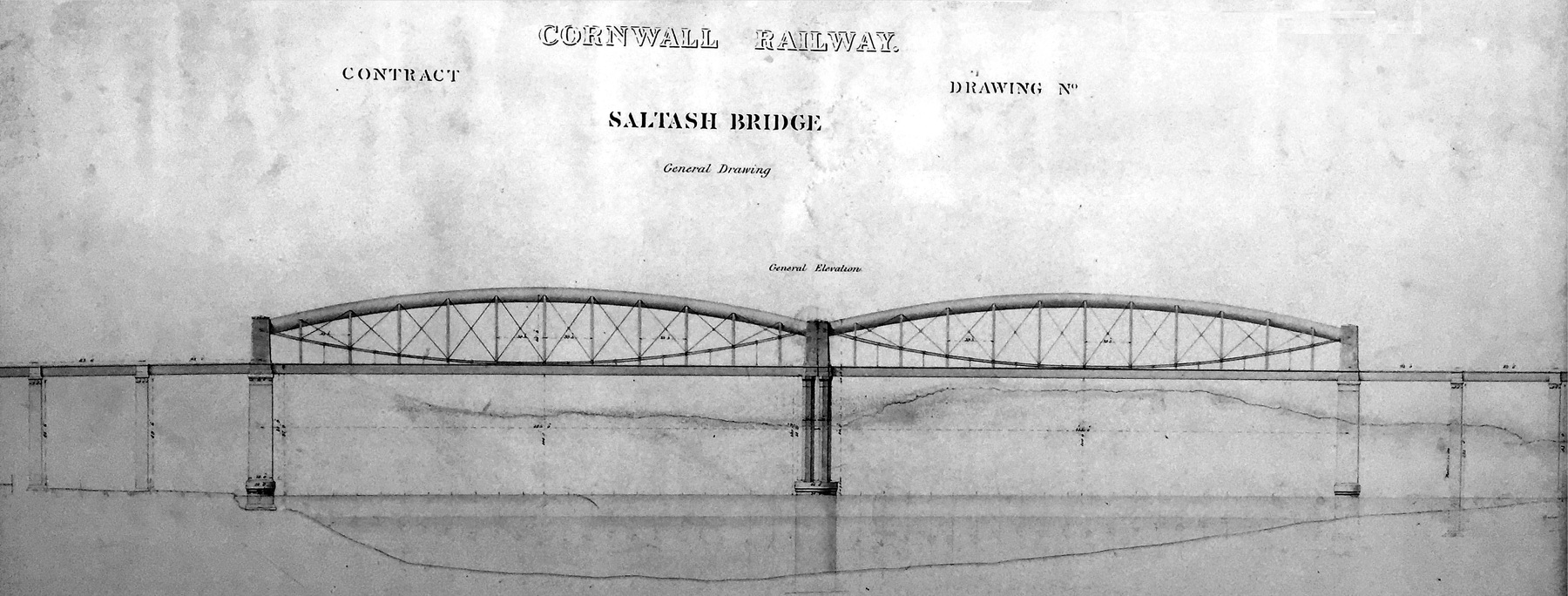

The first thing I wanted to see was the Royal Albert Bridge crossing the River Tamar between Plymouth and Saltash. The Cornwall Railway was one of the companies associated with the Great Western Railway (London to Bristol), and based on that Isambard Kingdom Brunel was assigned to build the important crossing. The bridge is of the lenticular truss design, a relatively unusual type, and the huge iron tube forming the upper arch is even more distinctive. Prince Albert himself spoke at the opening ceremony in 1859. Brunel was too ill to attend, and died a few months later, after which the railway company honored him by affixing very large letters at both ends of the bridge with the words I.K. BRUNEL ⋮ ENGINEER ⋮ 1859.

I detrained at Plymouth, because I wanted to take a stopping train to Saltash. This gave me some time to kill at Plymouth. I'm sorry to report that whatever remained of the Plymouth North Road station of 1877 was replaced by a rebuilding program completed in 1962. John Betjeman called it the "dullest of stations and no less dull now it has been rebuilt in copybook contemporary" and I have to agree. Outside, whatever charm there may have been in the station area has also been demolished to provide for wide vehicle-friendly boulevards. I didn't go farther than the foot tunnels into the North Cross Roundabout, a depressing circle of lawns and paved paths below traffic level, protected by ordinary steel barriers from at least smaller cars careering off the roundabout and flipping down the bank. I was not inspired to take photographs.

Here is an engineer's drawing of the bridge, from a sign in Saltash station.

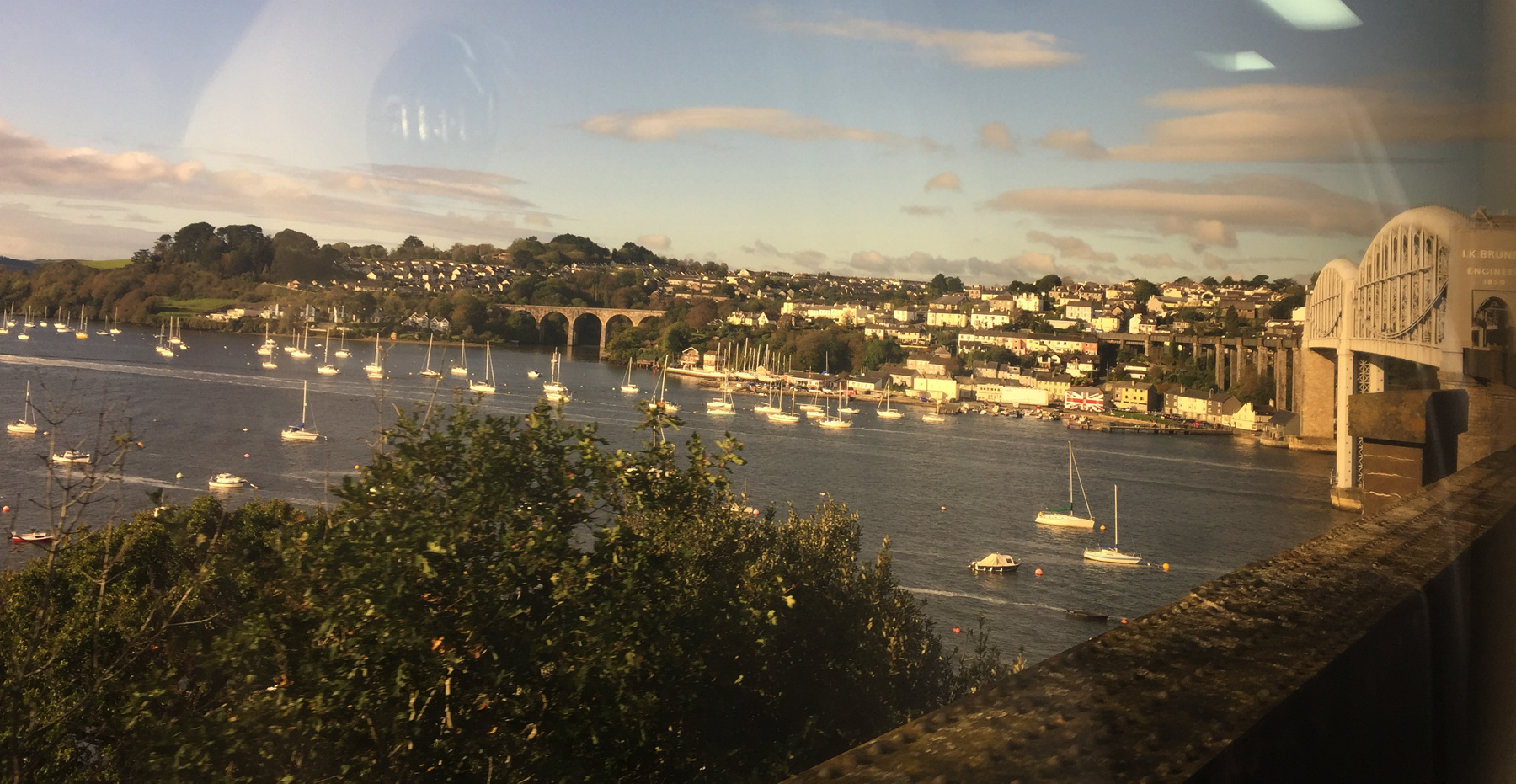

I grabbed a pretty decent view of the bridge from the train window. That's Saltash in the distance. After Saltash the railway runs on the arches to the left, the Coombe by Saltash Viaduct, originally a timber trestle by Brunel, replaced in 1894 by the stone structure.

Saltash station is immediately west of the Royal Albert Bridge. Below are two pictures from the end of the platform. The bridge is single track, but generously wide because of the original 7 foot ¼ inch gauge. The view today is compromised by the presence of the parallel Tamar Bridge, a suspension span for highway traffic opened in 1962, close by the Royal Albert and slightly higher.

The local authorities realize that people like me will stop at Saltash station, so they have put up a few large posters about the bridge and the county. Kernow a'gas dynnergh. People are trying to bring back the Cornish language. That's "Cornwall welcomes you" or literally "Cornwall to you welcomes". So the English name refers neither to corn nor to walls. Most scholars believe it is from Kernow (of uncertain origin) plus Old English wealas, "strangers".

Here comes my train.

My next stop was Liskeard. Just before you arrive you go over the Liskeard Viaduct, and down there is the Looe Valley Line, which is what I came to see. This blurry picture is from the window of a moving train. Yes, there are sheep.

The station at street level. The main line runs left and right behind it, in a wide open cut. The Looe Valley station is a short way down the street to the left. Station Road is on the right, crossing over the main line on a stone arch bridge.

Station Road is not ffordd yr orsaf because we are not in Wales. It's the totally different fordh an gorsav, which seems to me to be the same except for spelling conventions and the article in the middle.

The Looe Valley Line has its own station, called platform 3. It's well signposted from platforms 1 and 2 on the Cornish Main Line. You go up from those platforms and across a nameless road that gives access to some commercial properties, seen here on the right.

The first stop is St Keyne Wishing Well Halt, one of only two stations on National Rail with that once-common designation. "Halt" in a name alerted passengers to expect very few facilities, often no more than platform and a small shelter, and many halts were request stops. By this definition all of the intermediate stops on the Looe Valley Line are halts. A man on my train requested St Keyne Wishing Well Halt, and so I was able to grab a picture through the window while we were stopped. He is walking toward St Keyne village. There seems to be a mysterious rail on the ground to the left of the path.

St Keyne (pronounced "cane") is one of those early British saints about whom not much is known for sure. She was supposedly the daughter of a Welsh king, around the year 600, who became a hermit and yet also established many churches in Wales and Cornwall. In the nineteenth century some said Keyne must have been a man because a woman could not have done so much. Bah!

The station is named not only for the nearby village of St Keyne but specifically for the old well. A collector of old legends wrote in 1602: "The quality that man or wife ⋮ Whom chance or choice attaines ⋮ First of this sacred stream to drinke ⋮ Thereby the mastery gains." A story has been told about that. A young couple were married in the church at St Keyne, and after the ceremony, as the crowd of family and friends celebrated near the entrance of the church, the husband slipped away and ran to the well, and drank from its water. When he returned ready to boast, he found his new wife standing by a table with a pitcher on it, smiling at him and sipping water from a cup. She told him that she thought he might do something like this, so early in the morning she had gone to the well, and filled the pitcher, and hid it in the church. As soon as she saw him leave, she poured the water and was the first to drink of it. He had the good sense to grant that she had won the contest, and laughed at himself, and they lived happily ever after.

Looe is pronounced like "loo" and I wonder whether the spelling is intended to avoid any confusion with toilets. The name is from Cornish Logh, meaning a deep water inlet. Scottish and Irish have similar words meaning lake. Centuries ago there were two towns, Logh at what is now called East Looe, and Cornish Porthbyhan, across the river at modern West Looe. The first Looe station, 1879, was near the bridge linking the two sides of Looe, but the modern station from 1968 is a little farther north.

Here is the train at Looe, going back out a few minutes after it arrived.

Looe is a small town but manages to supply its full value of quaint narrow streets.

Scenes of the coast at East Looe, seen from the "banjo pier". There would be far more people here in warmer months.

If I had taken one more photograph to the right it would have shown West Looe and a great arch that supports the road along the cliff top. When I saw the arch I instantly thought, this is where the funicular in tunnel would have come out, where it would connect with a small ferry to East Looe. It was never completed and is mentioned in none of the references I have in a book or on the web. The Lost Funicular of Looe!

No, it was the Lost Mind of Joe. It was definitely time for me to go.

I guess I was too startled to take the picture.

(above) Image from Google Street View. Image capture: March 2016. © Freddie Hickes.

One more at Looe, looking upstream, taken while I was walking back to the station.

The Looe Valley Line has the brown signs for a heritage railway or railway museum— but it's a National Rail station operated by a main line company. Is there any other National Rail property signed like this?

Now we're coming up to the fun part. I planned out my time so that I would be riding back from Looe on a train on which I could request Coombe Junction Halt. Each day only two in each direction will stop here at the least used station in Cornwall.

For the year ended March 2015 it had seen only 26 passengers, but astonishingly two years later it had 212. That's still only 0.58 of a passenger per day. It was too soon for any All The Stations effect, since Geoff and Vicki did not visit the station and post the video about it until May 2017.

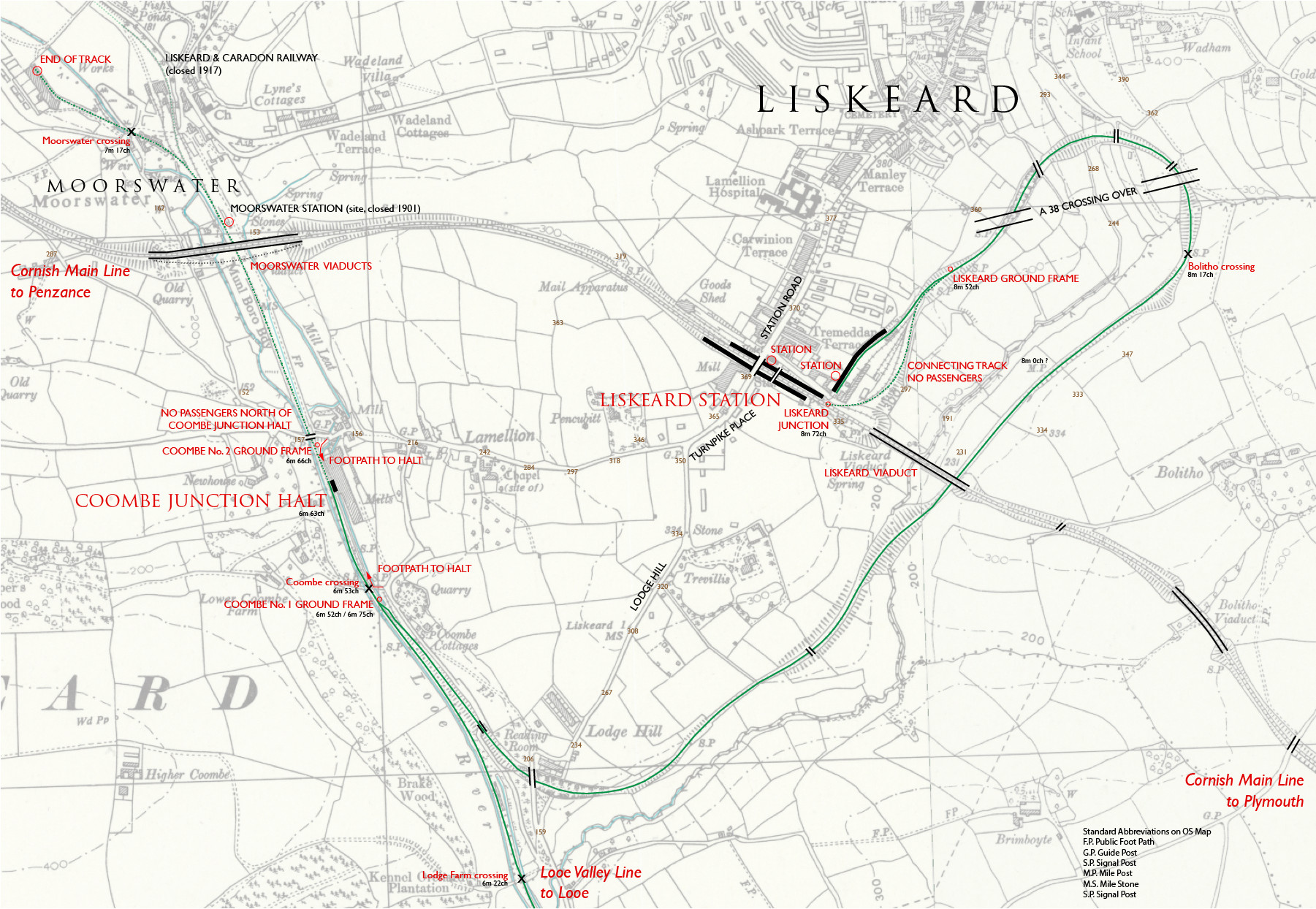

I found this small area an unusually interesting location, so let's have a map, and then we can go into detail about the history and the unusual current-day operation.

Base map: Ordnance Survey, circa 1910. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland given for non-commercial use only. Annotations by me based on my field notes, and checked with modern sources online and in print. In particular the distances are from: Trackatlas of Mainland Britain, 3rd edition, Platform 5 Publishing, 2017. (For more detail see the related series of six volumes from Trackmaps.)

The distance from Liskeard to Coombe Junction is about half a mile by road, but much longer by train. As you can see on the map the track makes a huge loop to the northeast and then back southwest, to conquer a difference in elevation of over 200 feet. The train takes nine minutes, because of the 2.5% gradient (quite steep by non-funicular railway standards) and the sharp curves.

The Liskeard and Looe Railway was opened in 1860 from Moorswater (upper left) to Looe, replacing an earlier canal of which remains can still be seen at places along the railway. To the north the Liskeard and Caradon Railway was opened in 1844 to transport copper, tin, and granite to the canal, and then to the Looe railway when it opened. The focus of the railway was the ore traffic to harbor at Looe, not passengers, so regular passenger service did not begin until 1879. The terminal at Moorswater was far from Liskeard town and station. In 1896 a halt platform was provided at Coombe, named for a nearby farm (and the Welsh word for valley), but while it was closer to Liskeard station it was still not convenient for most passengers.

The rail connection to Liskeard opened in 1901, forming Coombe Junction where it joined the original railway. The primary goal was to bring the ore trains up to the Great Western Railway, so the junction gave them the facing points. Passenger trains now originated from Liskeard instead of Moorswater, but they had to reverse direction at the junction, where a second track was provided to move the locomotive around the train and to allow ore trains to pass if need be.

I requested Coombe Junction Halt. While all trains have to run past the switch, most of them stop over the private crossing to Coombe House, and only two in each direction will run the extra 200 yards to the halt.

I waved to the guard as I got off at Coombe and walked forward to the end of platform to get this picture. The driver changed ends here. The rails are rusty in front of the train because this is as far as a passenger train goes. Looking through the openings in the shelter (there is no glass) you may be able to make out the white post and circular body of the Help Point.

Looking in the same direction, there it goes, the last train to Liskeard on this date. The slight reverse curve to the right is where the platform track joined the now-gone second track. The yellow lettering is the familiar "Sloping Platform, Apply Brakes" warning for passengers with wheelchairs or carts.

I walked along the footpath toward the junction. The water on the left is the output from the artificial diversion through the mill located next to Coombe Junction Halt. It rejoins the river proper, which is on the other side of the track, just beyond the junction. The bridge across the diversion is for the private road to Coombe House, but also serves as foot access to the halt. Notice the yellow telephone box.

This is how private crossings are controlled. They yellow telephone box is just off frame to the left. The small white sign on the gate reads, "Penalty for not closing gates £1000", and I don't know why it is not red like the others.

I went through the first gate and closed it behind me, and turned to the left. Here is Coombe Junction itself, seen from the crossing. Coombe No.1 Ground Frame is marked on the red shed, although it looks like the lever itself is in the next shed. There are light poles in this important area. I see no signal of any kind indicating the position of the switch in any of the three directions. Drivers are required to stop and look at the rails, or send out the guard to do so.

I want to emphasize that the guard from the train moves the points using the "armstrong" method. There is no remote central dispatcher telling a motor to move the points. On the train I took going out to Looe, the guard was accompanied by a young person in guard uniform who was learning how to do this task, an unusual one on modern railways.

The points are set for the Liskeard direction, which is of course where my train just went. But evidently Liskeard is the "normal" position, because in this video at 8:42, we see a train go toward the Looe direction and stop, while the guard moves the points back to the Liskeard direction, and then climbs onto the train. Loose cars from Moorswater are better routed up the hill than down to Looe— that might be it.

There's more to it than the switch. Track occupation is also controlled here. The section from Coombe to Liskeard is managed by an electric token system, a nineteenth century invention. There are two machines, at Coombe and Liskeard, connected by an electric current. The system has two states: all keys in, or not all keys in. In the former state, the guard can remove a key, giving the train the right to occupy the section, and no other keys can be removed from either machine. When the train reaches the other end of the section the guard inserts the key in the other machine. The section from Coombe to Looe is controlled even more simply, authorizing occupation if the guard is in possession of an object called a staff. This is practical because the section is a dead end of single track, and a train can only enter it from Coombe. On the Liskeard section there is sometimes a non-passenger train entering from Moorswater or the freight yard at Liskeard, so there needs to be a way to coordinate moves of more than one train.

I confess to trespassing a very short way alongside the track to get a close view of the points. I am now a wanted man. Then I went back through the crossing, and I swear that I closed the gate behind me.

There's an oddity at the junction. A law passed in 1845 required railways to measure their lines accurately and set up mile posts. Many fares were calculated by miles of travel. To identify intermediate distances more closely the companies used the surveyor's measure, 80 chains to a mile. On the Looe Valley Line zero is at the original end of track at Looe, and Coombe No. 1 Ground Frame is at 6 miles 52 chains. But its location is also given as 6 miles 75 chains "Liskeard Line". The double mileage is noted in the Trackatlas, which is very precise about these things. That's a difference of 23 chains. Where does it come from? The distance to Coombe Junction Halt is 11 chains— 22 chains there and back. Allowing a little rounding off, are they double-counting the distance to the halt, so that it measures how far a train runs instead of the length of track?

There's Coombe Junction Halt up ahead. You can see the Help Point slightly better from here. "When is the next train?" "What do you mean, tomorrow morning? It's only mid afternoon!"

This is the far end of the platform and the rusty rails. As you can see there is another footpath from this end of the halt to the road that crosses on the stone bridge.

Above and below: Coombe No. 2 Ground Frame. This controls access to and from the non-passenger track north of Coombe Junction Halt. You'll notice above that the points go into either a straight route or a derail. According to the notes on the Looe Valley Line Wikipedia page, linked above, the points here are normally set to derail in order to permit passenger train movements, but they are not so set here. The freight train actually needs the token from the No. 1 Ground Frame to go beyond this point, but since the two are visible from each other, the no man's land between them has been allowed. The picture below shows the lever that moves the points. Unlike No. 1, in this case the linkage to the track is not covered except by leaves.

"End of Token section" refers to the electric token system for movement to Liskeard controlled at No. 1. North of this point is yard limits. The other side of the arch has a similar sign that reads "Stop, Obtain token". It's funny that the footpath has the larger of the two arches. There is a trickle of a stream on the right.

The unpaved footpath continues parallel to the railway. I wandered out this way because I wanted to see the Moorswater Viaduct. I didn't know yet that there were two viaducts.

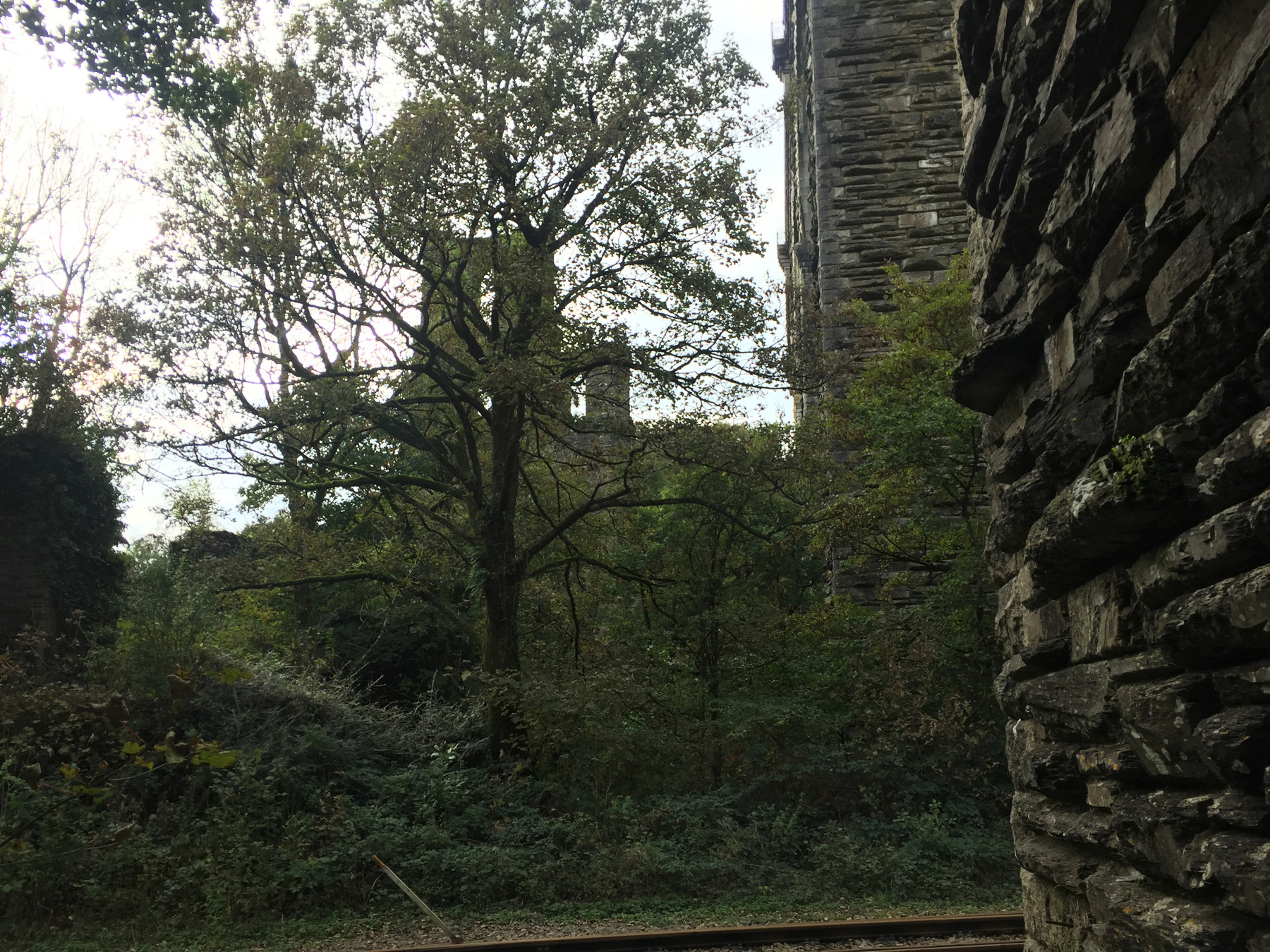

Isn't that impressive? The Cornish Main Line, operated by Great Western Railway, runs way up there on its way to Penzance in darkest Cornwall (as the bear might call it). I thought I had read that this was another Brunel masterpiece but it isn't.

There, in ruins, is Brunel's Moorswater Viaduct, what's left of it. His viaduct of 1859 had stone piers supporting timber frames that supported the single-track railway. The viaduct now in use was built in 1881, and some of the Brunel piers were removed afterwards before they collapsed. The remaining six are Grade II monuments but without any interpretive signs that I could see. The Ordnance Survey map I used up above shows eleven piers, but that was over a hundred years ago.

I walked back to the halt and up what could be called the main entrance, near No. 2 Ground Frame. Regardless of the very low passenger usage it has the usual generous Information posters.

The road down, near Coombe. I like the graphic on the sign about the road getting even narrower than it already is. Except up near Liskeard station, this road is not consistently wide enough for two cars to pass, and the turns are all obscured by walls or banks of earth like what you can see here. The Google Street View car did not venture down this way. That says something. I was concerned about driver reaction time upon seeing a pedestrian, but they went slow enough for me to survive. The steep grade concerned me less. I climbed the 199 steps of Whitby, didn't I. If you can enlarge my map enough you can see the spot elevations of 156 feet near the entrance and 369 at Liskeard main line station, and most of that rise is within the first part of the walk.

The itinerary suggests that it took me two hours to walk a half mile from Coombe. Now look, a good part of that was spent wandering around looking at ground frames and viaducts. But by bad timing I also just missed a train to Plymouth. That didn't affect things too much though, because I would have had to wait there for the same train I got later at Liskeard.

A lower quadrant semaphore at Liskeard. Horizontal is stop, and down at a 45° angle is "off" meaning the block ahead is clear. This design was at one time standard, but from the 1920s onward most British railways other than Great Western changed to upper quadrant. Horizontal always meant stop; diagonal up or down was clear. This signal also has colored lenses. The lower lens appears blue here, possibly to combine with a yellowish light to display green (or possibly it is an artifact of the camera).

TODAY'S FUNICULAR

None

TODAY'S ALE

The Globe, Looe: St Austell, Tribute (cask ale)

L'envoi

Thirteen funiculars in ten towns, and two more closed ones, all in June. I proved that it can be done in ten days, reaching all of them from a base in London. You do need to be relatively single-minded (although I strayed occasionally) and you must not mind getting up at dawn. And four months later I collected the loose ends of a few more closed ones and also-rans that are called cliff lifts. It was a good year. I had fun and that's why the url ends "fun".

I don't know where I will go in 2020. And neither do you.