FWP:

SETS

HOME: {14,9}

SHAME/HONOR: {3,5}

With such a clumsy-sounding and semantically limited refrain as kii sharm , it's not surprising that Ghalib composed only two verses, a kind of ghazal fragment, rather than a complete ghazal.

The first line sounds entirely like a complaint or lament. Some person or persons or thing or things-- which remain, thanks to the grammar of the ergative, entirely unspecified-- killed the speaker, and added insult to injury by killing him in a foreign land, far from his homeland. What could be a more heartless deed? What could be a sadder fate? The dead lover himself seems to lament it from beyond the grave; for more examples of the dead-lover-speaks situation, see {57,1}.

Yet after the requisite mushairah performance delay, we learn in the second line that the dead lover is relieved and grateful for such a death. In fact, he considers that the Lord must have been watching over him and somehow looking out for his interests-- if in fact the Lord didn't mercifully kill him himself (which remains the simplest grammatical reading). Why would the dead lover think that? Here are some of the possibilities:

(1) The lover's dying abroad, alone, means that nobody at home learned how poor and helpless and friendless he was in that land; nor did anybody in that land know his name or circumstances. So he's grateful not to have been embarrassed by the pity and/or scorn of people either at home or abroad.

(2) Dying in a state of helplessness and friendlessness abroad is no disgrace; it is what might happen to anyone who's alone in a strange country. But if the lover had died in the very same helplessness and friendlessness in his own country (as might well have happened), that would have been a shame and a disgrace indeed. He is thankful to have been spared such a humiliating fate.

(3) The lover wanted his helplessness and friendlessness to be perfect and complete, as an emblem of his passion, and a proof of his total indifference to public opinion and worldly success. He is grateful to the Lord for bringing this state of bekasii to perfection through the nature of his solitary, helpless death, which is just the kind a (Sufistic?) lover should have.

(4) The Lord knew that the lover was sick of this life, and wanted to die, but in that strange country he had no one around who would be obliging enough to kill him. (The beloved is often reluctant to perform this office, as in {19,4} for example.) So the Lord himself went ahead and, as a favor, killed the lover, thus helping him out in the embarrassments of his 'friendlessness'.

One really conspicuous thing in all this is the seemingly paradoxical double sense of the word sharm ; it would be hard to explain, except that we have the similar 'shame' in English. We can call the same behavior 'shameless' and 'shameful'; people who 'have no sense of shame' can 'live a life of shame'. In Urdu, sharm too goes in both directions; see {24,1} for another example of its complexity. And because it's the refrain in this ghazal fragment, it's also present in {83,2}, where the meaning of 'honor' emerges quite clearly.

So maintaining one's bekasii kii sharm , the 'shame/pride of one's helplessness' (see definition above), can mean: desperately concealing one's bekasii (out of shame or embarrassment); or living with it as best one can (so as not to act 'ashamed' of it and thus hurt its sense of proper pride/shame); or even adopting it as a value and flaunting it as openly as possible (out of sheer pride and perversity, or Sufistic self-lessness).

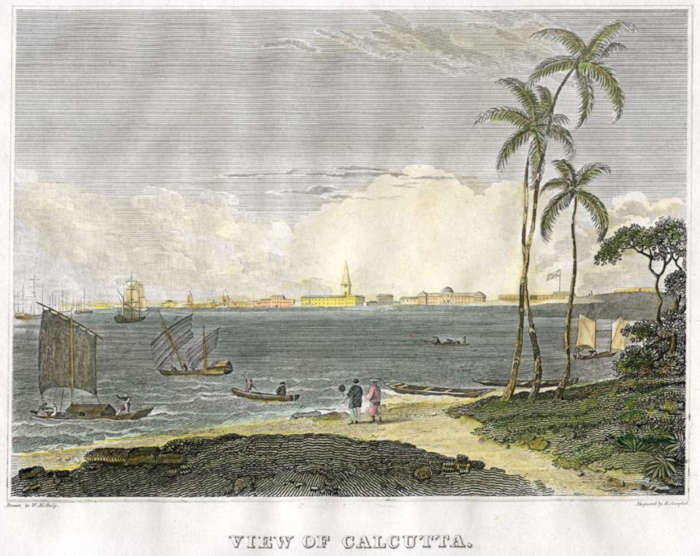

Just a point of cultural interest: Ghalib himself had a very

local sense of his 'homeland'. When he made his one big trip from Delhi to Calcutta, he wrote to friends

about being far from the va:tan . Compare {139,13x}, in which being outside the city of Delhi itself is described as a condition of 'foreignness' [;Gurbat]. Ghalib reached Calcutta in 1828; here is a view from 1826:

Hali:

Nobody wishes to die in another country; [but] he thanks the Lord for it, since if he lies without grave or shroud it’s no harm, for nobody knows who he was or of what rank. But to die in his own homeland, where everybody is aware of his circumstances but he has not even a single patron or sympathizer-- for the dead person’s dust to be dishonored like this would be a matter of severe disgrace and humiliation. Therefore he thanks the Lord that he has struck him down in another country and thus upheld the honor of his helplessness. Although outwardly this is an expression of thanks to the Lord, in reality it is from start to finish a complaint against the people of his homeland, which he has expressed in a strange guise.

==Urdu text: Yadgar-e Ghalib, p. 123