FWP:

SETS == HUMOR; OPPOSITES; WORDPLAY

Among other things, the word order may be a bit confusing in this one, so here's the prose order: goyaa nafii se i;sbaat taraavish kartii hai -- dam-e iijaad us ko jaa-e dahan nahii;N dii hai .

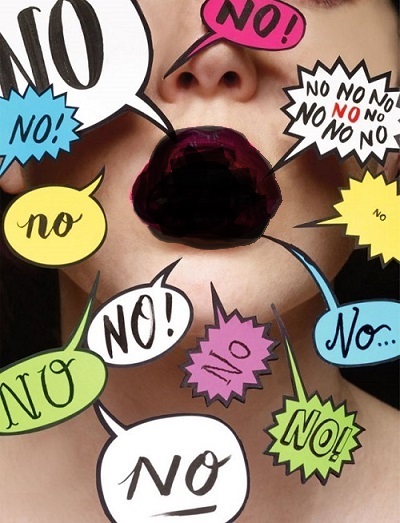

We know that the beloved has no mouth; for further discussion of this fascinating piece of ghazal physiology, see {91,4}. This verse plays on that basic truth with exceptional complexity. Consider the paradoxical thrust of the first line: from negation, affirmation exudes. The line's wild abstractness is energized by the weird idea of affirmation/proof as something that can 'drip' or 'ooze' (see the definition above). It's impossible to figure this out until we know the second line (which of course, under mushairah performance conditions, would be only after a tantalizing delay). Even when we do hear the second line, it's not easy to put the whole thing together. Here are two wonderfully contradictory possibilities:

=She denies/negates everything; that affirms/proves that

she has 'No' instead of a mouth.

=She says 'No' to everything; that affirms/proves that she has (some

kind of) a mouth.

Moreover, there's lovely wordplay. Despite Nazm's snide remark, the classic double meaning of goyaa -- both 'speaking' and 'so to speak, as if'-- has surely never been used to better advantage; for more on this, see {5,1}. The word taraavish is also amusing: we can well imagine that something can drip, exude, etc. from a mouth. And if that something is as abstract as 'affirmation/proof', the effect is still more piquant. (Compare the even more extreme {17,2}, in which 'desertness' is what drips.)

There's also the small clever pleasure of jaa-e -- literally, 'in the place of'-- where we would expect the usual bajaa))e, 'instead of'. The beloved doesn't just have 'no' instead of a mouth in some abstract sense, she literally has a 'no' on her face in the place where a mouth would be. And the 'no' issues itself forth as a (constantly repeated) word, so doesn't that mean the 'no' acts as a kind of mouth? There's an extra degree of realness here-- our imaginations are pushed closer to somehow envisioning her ravishing little face, with its rosy cheeks and that blank space of the nonexistent mouth between them, which of course isn't really empty because it contains 'no' where the mouth would be.

Abstractness, multivalence, wordplay, humor-- all in very high degrees, all mixed into a creative, spicy stew (and not blended into a vague porridge). What more can two small lines of poetry offer?

Note for grammar fans: the second line can be read as having either a perfect participle, 'is in a state of having been given'

[dii hu))ii hai], as Bekhud Dihlavi reads it; or a ne construction with subject omitted '[the Lord has given' [;xudaa ne dii hai],

as Bekhud Mohani reads it; in this verse it doesn't seem to make much difference.

Nazm:

That is, if her mouth is present, it's only out of necessity, it's only in the imagination. Otherwise, externally, she has been given, in place of a mouth, 'No'. The word i;sbaat the author has here used as feminine [contrary to the usage of Mir]. The author himself used it as masculine in {131,6}. Here the nearness of [the feminine noun] taraavish has deceived him. Those people who like .zil((a must find much pleasure from the word goyaa. But this word has become trite. (107)

== Nazm page 107