C. V. Starr Paper Gods Collection: Treatment Approaches and Challenges

The collection of paper gods in the C. V. Starr East Asian Library consists of prints created as ephemeral objects, which have survived because they were collected and housed for research purposes by Anne Goodrich and later by the East Asian Library. All are woodblock prints on thin paper, and many have been hand-colored. The vulnerability of this thin paper has led to various storage approaches, including mounting many of the prints on Kraft-paper linings. Mounting the prints probably preserved more of them for present-day researchers than would otherwise have survived; however, some prints have suffered extensive damage over the years because the linings are made of much heavier paper.

In-house conservation of the materials began in the early 1990s under the direction of Frederick Bearman. In this early phase of the project, tears in the unlined prints in the collection were mended, and polyester sleeves were created for them. At the end of this phase, all the unlined prints were stabilized.

The lined objects all had brown Kraft-paper backings that had been folded around the edges of the print, creating a frame. In the first group of "overall" linings, every surface of the Kraft paper was adhered, front and back, to the print. In the second, only the frame on the front of the print was adhered, while the back was left unattached. The latter process is called drummed-on, a bookbinding term for adhering a covering around only the turn-ins or edges. While the brown-paper border around the image in both groups was considered unsightly, the main cause for concern was physical wear in the drummed-on prints. Because the heavy paper in this set was not glued down everywhere, the lighter-weight paper of the print flexed slightly during handling. The stresses created by this movement against the hard-cut edge of Kraft paper caused extensive damage to the weaker paper of the prints.

Beginning in 1998, Alexis Hagadorn and Maria Fredericks began to investigate treatment for the prints on Kraft-paper backings. The purpose of this investigation was to determine 1) whether the overall linings could be removed at all, and 2) how to remove the drummed-on linings and address the damage to these prints.

The first tests carried out on the drummed-on linings revealed that the prints were attached with animal glue, a water-based adhesive made from processed animal bone or hide. Testing revealed that only steam would soften this adhesive to the point that the lining could be safely removed. To anticipate any danger to the artwork, the conservators tested inks and colors with water and any organic solvents that might be used during treatment. If any of the media were found to be soluble in a particular solution, then either that solution could not be used or it could not be allowed to come into contact with the colorant. Results of this testing showed that the colorants were all more or less soluble in water and that the red colorant was extremely sensitive.

The most successful technique for removal involved slitting the edges of the Kraft paper where it had been turned over so that the back of the lining could be removed. Then steam could be applied in small segments along the border, allowing the conservator to work quickly to remove the lining while controlling the moisture.

This technique solved the problem of removing the lining paper from the drummed-on group, but two problems remained: what to do with the weakened and damaged paper prints after the linings were removed, and whether a way could be found to remove the linings adhered overall. Since the colorants were extremely moisture-sensitive, steam could not be applied to the overall linings.

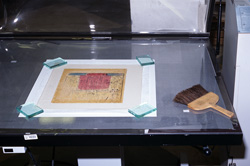

Preparing the lining paper.

Water is brushed on an intermediary sheet to humidify the print.

During work on the lining removal in 2000, Columbia's conservators suggested that the Starr Library bring in an outside consultant on the project. Betty Fiske, paper conservator at the Winterthur Museum, Library and Gardens, who has specialized in treatment of East Asian art on paper, was invited to examine the prints and develop a treatment protocol for the lab. In the first phase of her investigation, she and Fredericks tested various fixatives with the goal of finding a material that would prevent movement of the sensitive media during wet treatment. While several solutions did prevent movement of the colorants, all were eventually rejected because it was determined that they would cause other undesirable visual effects or because of concerns about the potential for damage to the fragile paper.

Ultimately the decision was made to not treat the paper gods with overall linings. The Kraft-paper frames were not aesthetically pleasing, but they were not causing further damage to the prints. The adhesive also had not caused staining and was not expected to undergo further deterioration that would damage the prints.

For the paper gods with drummed-on linings, the decision was made to reline the prints after removing the Kraft paper to give them the strength to withstand future handling. The most desirable adhesive for the new linings would normally be diluted wheat-starch paste. The use of this adhesive under standard lining procedures could be expected to cause the sensitive colorants in the paper gods prints to move. Fiske determined that it would be possible to apply the lining with starch paste by carefully controlling the moisture. Following her protocol, the Conservation Lab staff first gently humidified each print by rolling it in a dampened piece of paper. Linings of handmade Japanese paper were pasted out. The lining paper was placed on the suction table, and as one person placed the print down on the lining, another immediately activated the suction. In this way, moisture was quickly drawn away from the print, while the print was simultaneously drawn in close contact with the lining. Each print remained on the table under suction until it was completely dry. As a result of this treatment, the prints were strengthened by the lining paper but retained much of the light, flexible character they had when they were created.