The New Year's prints, or nianhua 年畫, displayed on this Web site, represent one moment in a long and vibrant history of this popular art. While the origins and development of popular art forms and popular religious practices are almost impossible to trace with any certainty, there is a limited amount of information about the practices and beliefs that led to the creation of mass-produced, colorful New Year's prints.

The earliest extant textual reference to the use of efficacious images for protection occurs in a passage from the Shanhai jing 山海經 (c. 4th–2nd c. BCE). According to legend, a pair of guardian deities, Shenshu 神荼 and Yulü 郁壘, were stationed on Mount Dushuo in the middle of the sea, at the gate through which all ghosts and demons passed between the earthly realm and the underworld. They would separate the good from the evil, bind the evil demons with reeds, and feed them to tigers. The Yellow Emperor devised a ritual to expel all evil demons: he set up some large figures of peach wood, and painted images of Shenshu and Yulü, along with some tigers, on the gate.1

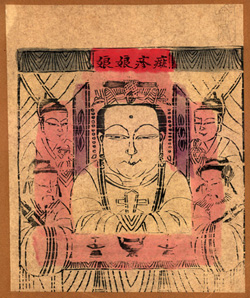

NYCP.GAC.0001.0070

Banzhen Niangniang

癍疹 娘娘

With the arrival of Buddhism to China in the late Han dynasty (220 BCE–220 CE) and Six Dynasties period (220–589 CE), came new deities and new pantheons for worship and display, and by the Tang dynasty (618–906), the art of depicting protective deities and devotional images for display in the home reached new heights. However, it was not until widespread development of printing technology in the Song (960–1279) dynasty that what we now call New Year's prints became an essential part of the New Year's celebration for the majority of Chinese families. The prints did not flourish under the Mongol Yuan (1279–1368), but were revitalized and refined during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, which witnessed the rapid development of new technologies, the addition of scenes from novels and opera, depictions of beautiful women, and even satirical content.

China's push for modernization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries threatened to wipe out the long tradition of New Year's prints completely. In 1931, unaware of the outcome of the social upheavals taking place, Anne S. Goodrich walked into the Renhe zhidian 人和紙店 (Unity Among Men Paper Shop) in the eastern quarter of Republican Beiping (Beijing), and "asked for every print they had in stock." Indeed, the future did not look promising for a foreigner in Beijing or for the traditional New Year's prints.

The last Qing emperor abdicated his throne in 1912, and China entered what is known as the Republican period. Nominally, the Nationalist Party, or the Guomingdang (GMD), held power, but in fact many areas were ruled by powerful local warlords, and the GMD had to deal with the growing Chinese Communist Party (established in 1921) as well as the invading Japanese.

In 1924, Sun Yat-sen called for a nationalism specifically directed against foreign imperialism, which was followed in 1927 by anti-imperialists attacks on foreign businesses and homes in several cities. Chiang Kai-shek established the Nationalist capital at Nanjing in 1926 and moved north to take Beijing two years later.

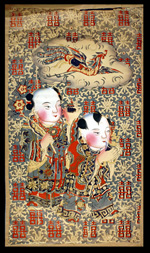

NYCP.GAC.0001.0143

He He er Xian

和合 二仙

During the last years of the Qing dynasty and into the Republican period, anti-imperialist and anti-feudal New Year's prints were designed and gained popularity. The art form was popular among revolutionaries precisely because it was "popular," or of the masses. Meanwhile, traditional New Year's prints were under attack for other reasons. With the promulgation of a set of laws entitled "Standards for Preserving and Abandoning Gods and Shrines," the Nationalist government declared "superstition" an "obstacle to progress" in 1928, and set out to condemn superstition in all its forms. Yet these laws were far from consistent in determining exactly which religious practices and objects would be acceptable: one could worship Confucius, Guandi, or the bodhisattva Guanyin, but Daoist deities, charms, and certain nature gods were declared superstitious.2 With haphazard and inconsistent reasoning, the Standards allowed for the worship of the stove god, the earth god, and certain nature gods, while worship of the city god, the dragon god, the rain god, and the god of wealth was banned.3 The larger project seems to have aimed to protect "organized religions with authoritative texts," especially organized Buddhism.4 Had the Standards had been enforced to the letter, they would have banned many of the prints in this collection—in cases of pantheons containing both Buddhist and Daoist figures, the prints would have had to be cut in half. It is a testament to the disparity between the dominant narrative and popular practice that three years after this promulgation was issued, a little shop in downtown Beiping showed no signs of dividing its gods accordingly.

1. Cited in Bo Songnian 薄松年, Zhongguo nianhua shi 中國年畫史 (Shenyang shi: Liaoning meishu chubanshe, 1986), 2. See also Po Sung-nien and David Johnson, Domesticated Deities and Auspicious Emblems: The Iconography of Everyday Life in Village China, Popular Prints and Paper Cuts from the Collection of Po Sung-nien (Berkeley: Chinese Popular Culture Project, 1992), 105.

2. From Zhonghua Minguo Fagui Huibian [Collection of the Laws of the Chinese Republic] (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1933), 807-814, cited in Prasenjit Duara, "Knowledge and Power in the Discourse of Modernity: The Campaigns Against Popular Religion in Early Twentieth-Century China" (Journal of Asian Studies 50/1 (1991.2): 67–83), 79.

3. Sakai Tado, "Gendai Chūgoku bunka to kushūkyō" (In Niida Noburo, ed. Kindai Chūgoku no Shakai to Keizai, Tōkyō: Tōko Shoin), cited in Prasenjit Duara, "Knowledge and Power in the Discourse of Modernity: The Campaigns Against Popular Religion in Early Twentieth-Century China" (Journal of Asian Studies 50/1 (1991.2): 67–83), 79.

4. Prasenjit Duara, "Knowledge and Power in the Discourse of Modernity: The Campaigns Against Popular Religion in Early Twentieth-Century China" (Journal of Asian Studies 50/1 (1991.2): 67–83), 79.