The prints in this collection were all personal and purchasable, and the people who bought them believed they would have good luck. Yet even a quick perusal of the collection will leave one with the impression that the quality of these prints varies enormously. Some are no more than a nondescript image of a male or female god stamped in black ink onto a sheet of coarse paper; some consist of those same images embellished with broad brushstrokes of color—red is predominant, but one also finds occasional strokes of blue, yellow, purple, green, and orange. A second group of prints stands out against these as lively and radiating with brilliant colors that are carefully integrated into the image itself. This type of coloring is achieved through the process of stamping a sheet of paper with a series of identical woodblocks, each bearing a different color, and is sometimes supplemented by hand painting. A small number of prints made with this more labor-intensive coloring technology nevertheless fits better into the first category (see, for example, the pantheon represented in 183).

There is a simple explanation for the differences among the prints: most of the former, plainer prints were not displayed at all. Rather, these paper gods were purchased at New Year's, and enjoyed offerings and a ceremony in the home. At the end of the ceremony, they were burned to send them off, ready to watch over the family and intercede in Heaven on their behalf throughout the year. These prints were known as zhima 紙馬 (paper horses) since, as Yu Zhaolong 虞兆隆 of the Qing explained, "because the gods and buddhas are carried by the paper, it is like a horse."1

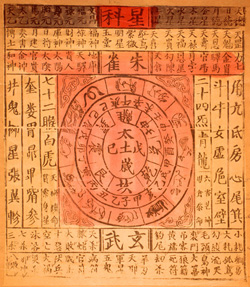

NYCP.GAC.0001.0116

Xing ke

星科

The majority of the zhima are likely what was known in Beijing and certain other areas as baifen 百分 (the hundred gods), which were sets of several dozen gods, cheaply made, that worked in the same way as the various pantheons of gods.2 These would be purchased as a set, receive a ritual offering directed toward "all the gods of the three realms," and then be burned. A number of them are not gods at all, but spirit money and supplies that will be delivered to ancestors by burning (e.g., 164, 172, 182). Certain prints make more use of text than is common to New Year's prints, such as 50 and 116, which are written charts of all the stars that are anthropomorphized in other prints, and 170, a sutra surrounding an image of Guanyin. Prints such as 161 and 163 conceptualize a god on earth rather than in a non-distinct heavenly realm; we see him through the front door of a temple—as a statue. Also distinctive to this collection are several images that have been cut in half, with only the top half preserved (nos. 61–66). Neither paper nor the simple prints were worth much money, but perhaps the head was the vital section of the god, and two gods per sheet was occasionally adequate.

The colorful prints that comprise the second group had a more intimate and extended relationship with the family. Prints of the stove god and the gods of wealth are zhima as well, but they held a more prominent place in the home than the baifen. The print of the stove god, complete with a calendar, was displayed year-round in the kitchen, where it received offerings and monitored the family's behavior throughout the year. During the New Year, a new stove god would replace the old, who would be dispatched to heaven by burning to make his report to the gods. The god of wealth would be displayed at the family altar each New Year, where he would enjoy offerings and in return would watch over the family's financial situation.

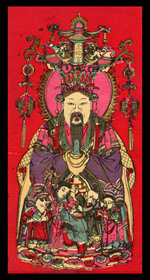

NYCP.GAC.0001.0047

Ding fu gong

定福宮

Yet by far the most visible, and also the most exquisite, of the prints are the door gods 門神. These prints, usually produced in pairs that faced one another, were pasted on or around the door during the New Year's festival, where they would remain to guard the home throughout the year. Door gods ranged from fearsome protective demon-quellers, such as Zhong Kui, to such auspicious images as the twin immortals, He 和 and He 合, or happy children. The image of the immortals He and He also exemplifies the practice of depicting objects that are homophones of the desired result: prints 143 and 168 show He and He, one holding a lian 蓮 (lotus) and the other with a sheng 笙 (reed mouth organ). These two syllables combine to form the term liansheng 連生, which means "one birth after another." Another example is found on print 47, where images of yu 魚 (fish) near each edge of the print are "read" as yu 餘 (enough to spare). These are just two examples of the rich imagery and symbolism that make New Year's prints meaningful—and even legible—to Chinese people of all backgrounds, regardless of their education.

NYCP.GAC.0001.0075

Zhong shen

衆神

Most of the prints of door gods in this collection were purchased from major centers of production located throughout China. Most centers were founded in the Ming dynasty and flourished throughout the Qing. Among the most influential production centers were Yangliuqing, near Tianjin; Taohuawu in Suzhou; Wei County in Shandong; Wuqiang in Hebei; and Zhuxian Village in Henan. Each center developed its own distinctive styles and circulated its prints throughout China. While he was living in Beijing, Lu Xun remarked that he had seen door gods from Henan growing up in his hometown of Shaoxing.3 A number of these distinctive Henan door gods were also for sale in Beijing in 1931 (see prints nos. 39–40, 75–77, and 134).

This collection, consisting of both local zhima and nationally reknowned door gods, is testament to the wide circulation of famous prints and the simultaneous popular demand for the cruder and more fleeting gods that would hurry off to heaven on one's behalf.

1. Yu Zhaolong 虞兆隆, Tianxiang lou oude, mazi yuyong 天香樓偶得,馬字寓用. Cited in Tao Siyan 陶思炎, Zhongguo zhima 中國紙馬 (Taibei: Dongda faxing, Sanmin jingxiao, 1997), 2.

2. Bo Songnian 薄松年, Zhongguo nianhua shi 中國年畫史 (Shenyang shi: Liaoning meishu chubanshe, 1986), 116–117.

3. Bo Songnian 薄松年, Zhongguo nianhua shi 中國年畫史 (Shenyang shi: Liaoning meishu chubanshe, 1986), 176.