FWP:

I don't have much to add to Faruqi's comments, except to point to the enjoyableness of the word-and-meaning-play: after having fled on foot, the speaker has been (re)captured and punished by being made to press the feet of his captor, the highway-robber. For more on foot-pressing, see {193,5}.

The following verse, {121,4}, has the same 'can't win for losing' tone; though as Faruqi emphasizes, it's paradoxical rather than wry or ironic.

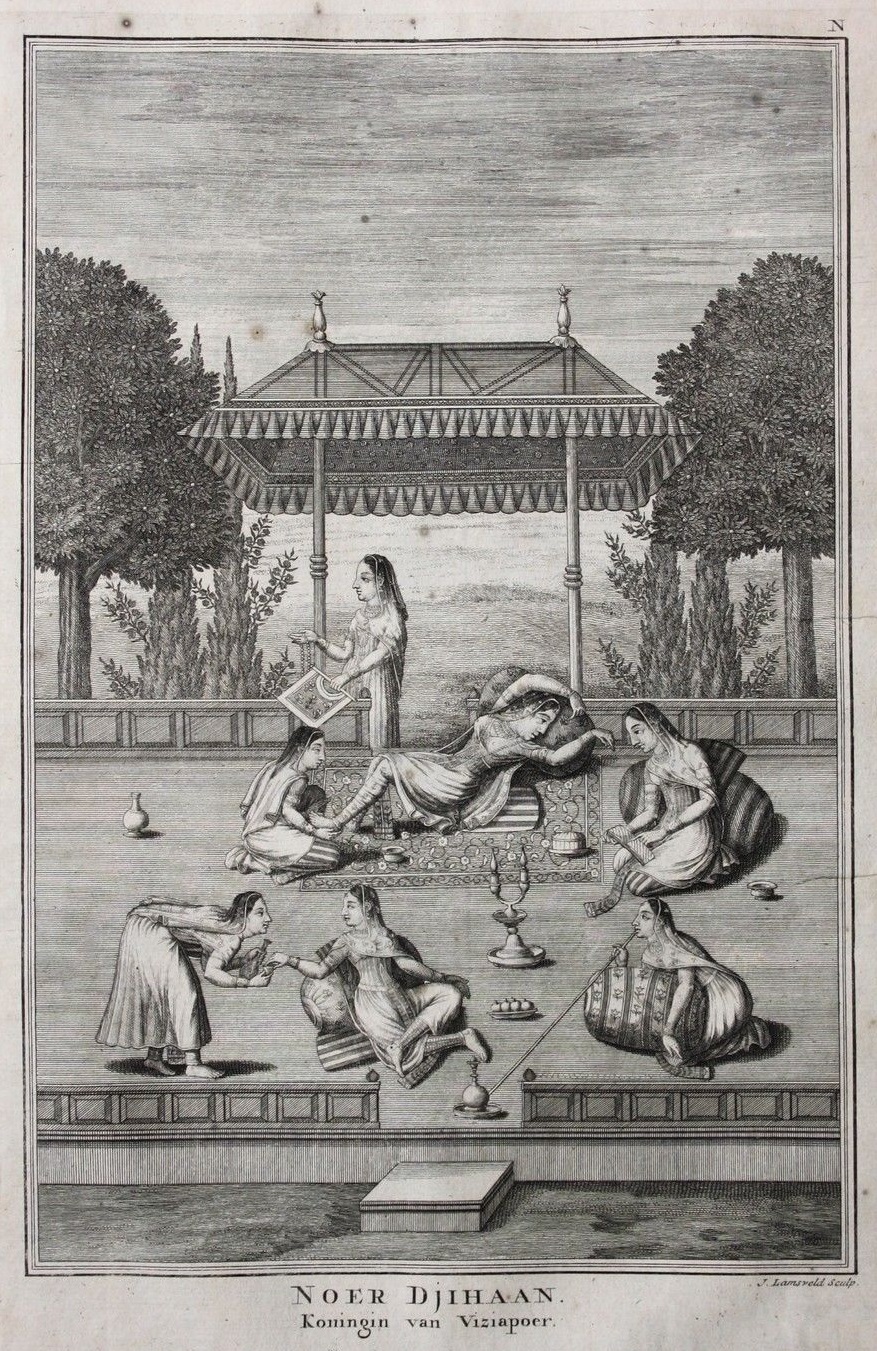

Here's a depiction by Francois Valentijn (Amsterdam 1726) of 'Nur Jahan, the Queen of Bijapur' having her feet pressed:

Hali:

Mirza's most intimate pupils and friends, among whom there was no formality, often used to come and sit with him in the evenings, and at such times Mirza, in a state of intoxication, used to say extremely enjoyable things. One day Mir Mahdi Majruh was sitting with him and Mirza, lying on a cot, was groaning. Mir Mahdi began to press his feet. Mirza said, 'Brother, you're the son of a Sayyid, why do you make me a sinner [by freely performing such a lowly service for me]?' He [Mir Mahdi] didn't accept that, and said, 'If that's your view, then please pay me for pressing your feet.' Mirza said, 'Indeed-- there's no objection to that'. When he [Mir Mahdi] had finished pressing his feet, he asked for his payment. Mirza said, 'Brother, what payment? You pressed [daabe] my feet, I 'pressed'/suppressed [daabe] your payment-- the account has balanced out!'

==Urdu text: Yadgar-e Ghalib, pp. 71-72