FWP:

It's an angular, awkward, disquieting verse, isn't it? The commentators take it at face value, as a small sententious lecture on the virtues of education and self-improvement. They ignore the conspicuous ways in which this moral lesson is undercut.

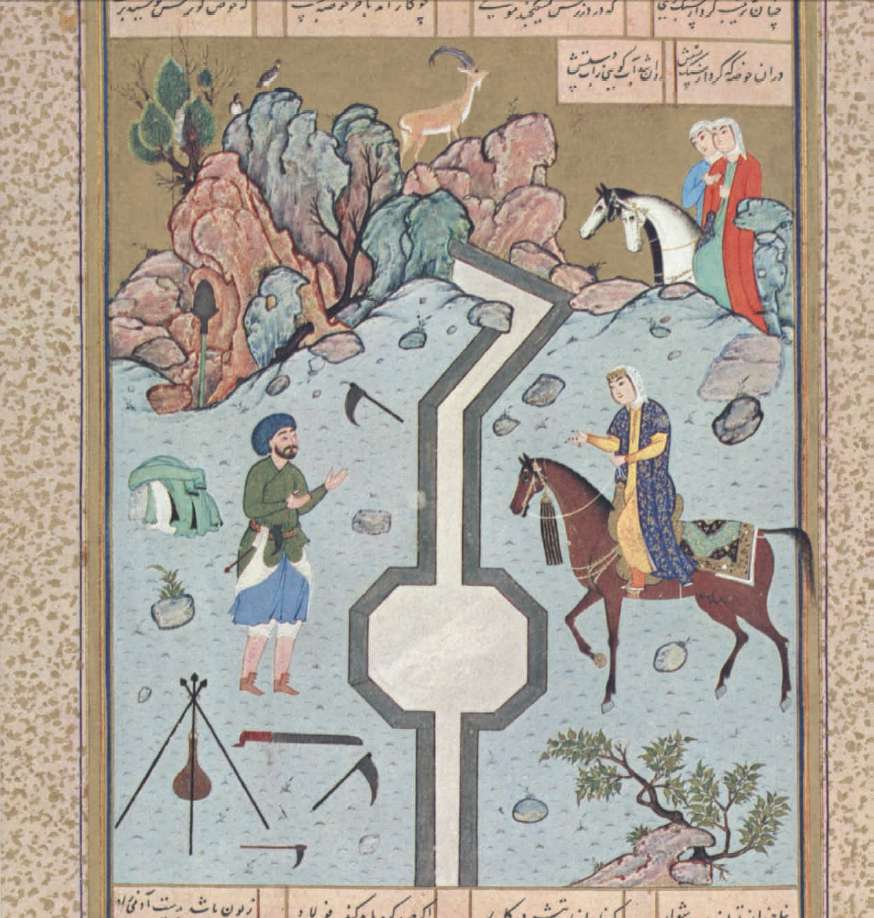

The first line seems unsettling on the face of it. One problem is the role of the 'speech-sharing' between the stone-worker Farhad and Shirin, the aristocratic beloved of King Khusrau. Farhad's stone-cutting powers did, no doubt, give him the chance to speak with Shirin. The image below illustrates a scene from Nizami's famous version of the story (see Peter Chelkowski et al, 1975: pp. 21-48). But Ghalib knew that the 'conversation' between the two had led-- through various narrative convolutions-- to Farhad's doom.

The second, and more obvious, problem in the first line is the role of the 'axe' itself. A reference to Farhad's 'axe' makes anyone who knows the Urdu ghazal version of his story think first of his great, impossible task or ordeal of stone-cutting (he's not called 'Kohkan' for nothing)-- and then of his use of the axe to kill himself (see, most notably, {3,6}) when he hears a false report of Shirin's death. These axe episodes-- monumental, grim, and deadly-- loom over Farhad's whole fate. So after we've heard the first line, we're left puzzled by its incongruity, its perverseness, its generally uneasy quality.

Then what do we find in the second line? A sort of faux-naïf, Pollyanna-ish truism. Everything in the first line has already conspired to 'problematize' the second line, and such a blandly problem-denying second line is screaming loud and clear, 'Doubt me!'. Needless to say, we do. Even without the highly doubt-demanding first line, the very tone of the second line invites disbelief. Is it really always good for anybody at all to have any skill at all? And in this case, haven't we just seen a major, counterexample-- a case in which somebody's skill got him only a very limited slice of the good claimed for it (the chance to fall in love, and converse with his beloved), while as a direct result, causing him to be tricked into splitting his own head open with an axe? Doesn't the second line have the false good cheer of someone trying to skate smoothly over a horrible moral and ethical chasm? (Someone like a Polonius?) Ghalib has set up for us a deliberately sententious little maxim that he not only invites us, but unmistakably and forcefully enjoins us, to doubt.

But then, of course, we can also have doubts about our doubts. This is, after all, a lover speaking. For Farhad to be in communion with his beloved through his hope and passion, through the reward promised for his stone-cutting ordeal-- what could be more lover-like? And for Farhad then to die because of his passion-- for a true lover, what better fate is possible? It's just conceivable that, since the lover's whole cult of pleasure-in-pain is the bedrock of the ghazal world, the lover is speaking with complete seriousness, urging everybody to go out and learn a skill, so they can perhaps be lucky enough to attain a degree of 'accomplishment' that will win them a fate like Farhad's.

For another example of Ghalib's complex, unresolvable thoughts about Farhad and Shirin, see {42,6}. The present verse also seems to belong, in its heavily apparent sarcasm, to the 'snide remarks about famous lovers' set; for others, see {100,4}].

Compare the second line in the present verse with the second line of the next verse, {174,8}.

Nazm:

In the first line there is 'awkwardness' [ganjalak], and in the second one a [phonetic] 'clash' [tanaafur], and between the two lines the connection is not good either, and the theme too is nothing at all. (195)

== Nazm page 195