Dublin and Kingstown Railway

Dún Laoghaire

In which Joe investigates Dún Laoghaire, once Kingstown, past and present, describing where the atmospheric railway was and how it worked, and digresses on the place of Pearse station in railway history.

Explorations: Thursday, 21 June 2018, and Tuesday, 15 October 2019

Journey: Dublin Pearse to Dún Laoghaire Mallin, DART

-

OFTEN CITED REFERENCES

- Howard Clayton, The Atmospheric Railways, the author, 1966.

- Charles Hadfield, Atmospheric Railways, David and Charles, 1967.

- Rob Goodbody, The Metals : from Dalkey to Dún Laoghaire, Dún Laoghaire Rathdown County Council, 2010.

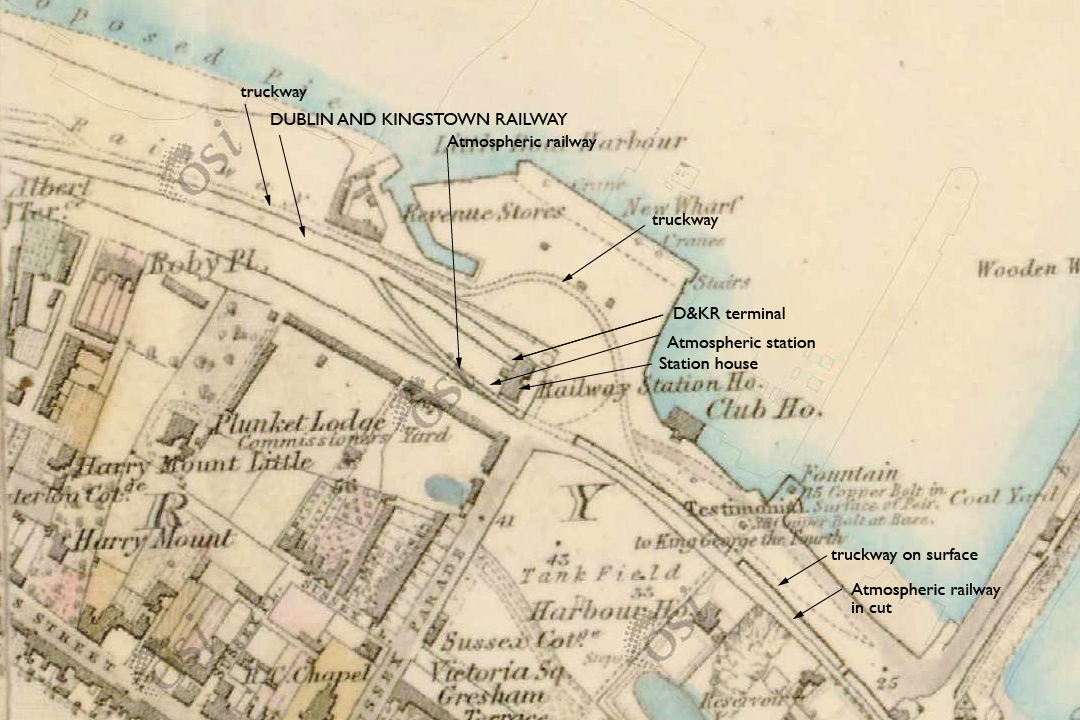

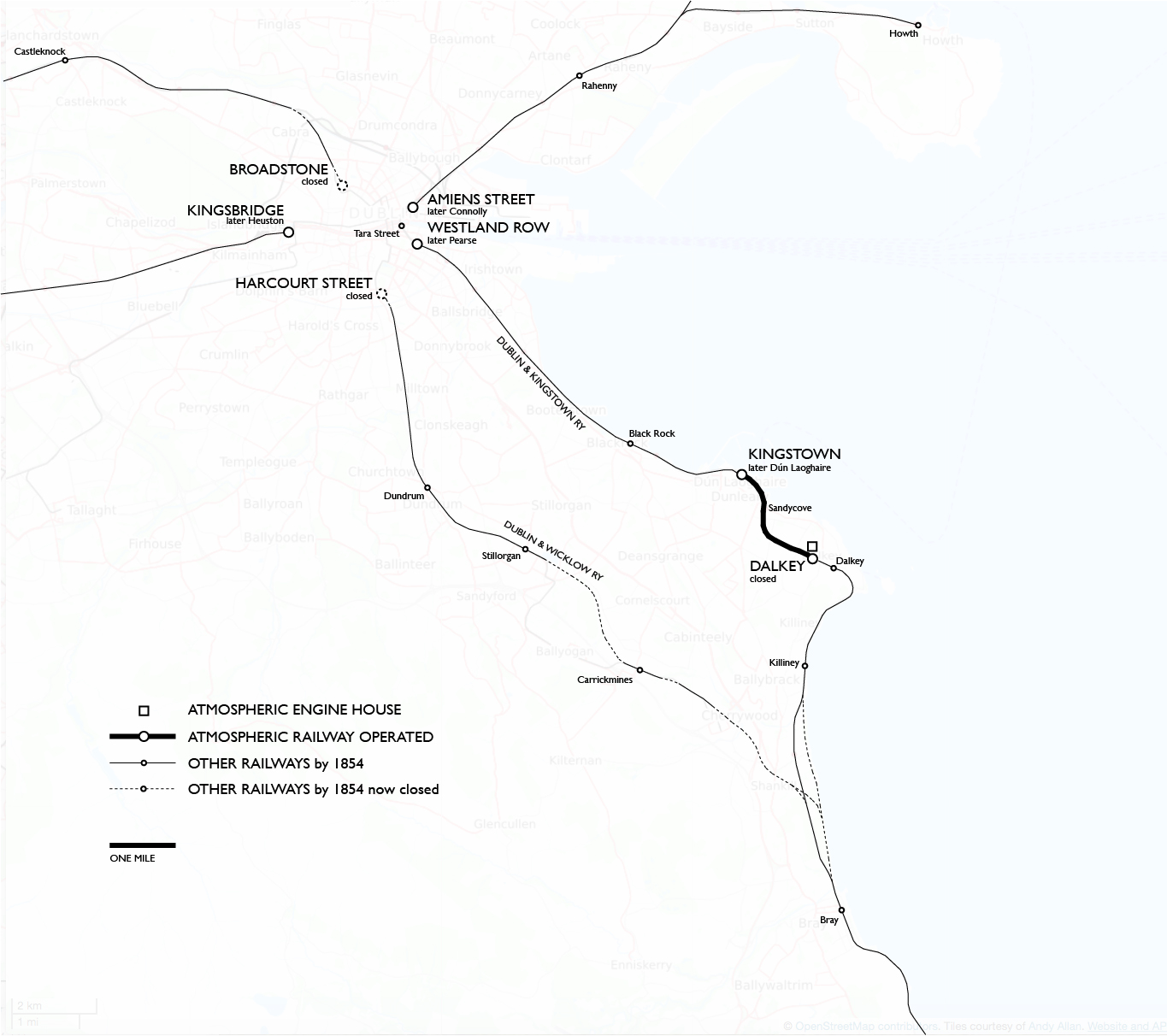

Our first stop is the first atmospheric railway. It is now part of the main line from Dublin running south along the east coast. The map below shows its position relative to the Dublin and Kingstown Railway and to the larger Dublin and Wicklow system of which its route, no longer atmospheric, became a part.

The map also shows other railways opened by 1854, the year the atmospheric ceased operations. The now-closed parts of the Dublin and Wicklow Railway are those that were not incorporated into the LUAS Green Line, and a section along the shore that was relocated inland to avoid coastal flooding. I inserted one later element, the Tara Street station.

I began my journey in 2018 at Tara Street and in 2019 at Connolly. In the latter year I left the DART train at Pearse to take a look around the original starting point of trains to the south.

Pearse was called Westland Row until 1966. The station was designed by Charles Vignoles, the Irish railway engineer who also supervised the atmospheric railway installation. It was above street level as it is now, but the trainshed had then two parallel peaked roofs to cover three tracks with platforms and a siding. The present overall roof with space for five tracks dates from the 1880s. My photos suffered because of scaffolding inside for major repairs to the roof, so in their place I have used the excellent view below by the prolific Ben Brooksbank.

The most notable change to the station was the opening of the north wall in 1891 for the City of Dublin Junction Railway that made it possible for trains to run through between the terminals Pearse and Connolly. The DART trains take full advantage, calling also halfway between at the little Tara Street station by the River Liffey.

The Dublin and Kingstown Railway was the first railway in Ireland. At its opening on 17 December 1834 trains ran from Westland Row to a location at Monkstown near the west pier of the new harbor at Kingstown. To advance to a more central location between the piers, the company spent two years more negotiating with the authorities. The sticking point was a causeway that would close off most of a small cove called Dunleary Harbor, for which permission was finally secured. The railway reached its desired terminal in 1837, on the site of the present day Dún Laoghaire station. The D&KR formed an important connection for passengers and freight, and its success led to organization of other railway companies in Ireland.

— Kingstown Harbor, Dún Laoghaire, seen from Dalkey Hill, 2018.

Granite for the long piers that enclose the harbor was brought from the quarries above Dalkey starting in 1817 on a "truckway", a light railway. The four-wheeled trucks that carried the granite were first lowered down on a series of three inclined planes on the steep upper portion and then by horses on the easier grade of the longer lower portion. Even before the D&KR was completed the company proposed an extension to Dalkey, and in 1838 they inquired with the Board of Works about using the truckway property to do so. By that date the harbor was substantially complete, and with reduced traffic the double track truckway had been reduced to a single track. The company's immediate goal was to develop a business exporting stone with better transportation than the poky horse drawn trucks. Increased population around Dalkey was expected as a future source of revenue.

Though the truckway was level alongside the harbor, as it turned inland it went up a curved one per cent grade that increased to two per cent as it neared Dalkey. Even one per cent was considered too steep for early locomotives, but in 1840 James Pim, treasurer of the D&KR, was inspired by a half-mile demonstration of an atmospheric railway that he saw in London, which ran up a one per cent grade without difficulty, and was said to be capable of much steeper grades because it did not rely on traction between the smooth surfaces of wheels and rails. The inventors behind it were Samuel Clegg, an expert in gas pipes, and the ship builder brothers Jacob and Joseph D'Aguilar Samuda. Clegg soon left the enterprise, but the Samuda brothers, eager to see the invention put into practical use, offered to make their patents and expertise available to the D&KR at no charge. Work on the atmospheric railway began in September 1842, with Vignoles as company engineer.

The atmospheric railway was built as a single track of standard gauge (4 feet 8½ inches) running in open cut all the way except at the upper end where it rose to the surface. The cut not only avoided dealing with the obstacle that the tube posed to level crossings, but because of it and no need for compulsory purchase of land, the railway could proceed without Parliamentary permission. Still, public roads must have been affected by construction where bridges were built for them to cross over the cut. Some cost saving was achieved by making the cut no larger than necessary, just 12 feet wide and with a clearance of only 8½ feet under the bridges.

The Ordnance Survey map below shows the arrangements at Kingstown during the atmospheric period. The atmospheric track branched off north of the D&KR station. It had its own platform located next to the main station, and then went off into its own route. Passengers had to change trains at Kingstown.

Atmospheric operation on the 1.75 mile "Kingstown and Dalkey Railway" was tested in August 1843 with trains running down only as far as the bridge at Sandycove, because the difficult work near Kingstown was not yet completed. Scheduled atmospheric service from Kingstown to Dalkey, with no other stations, began on 29 March 1844. The pipe was of 15 inch diameter cast in sections ten feet long, the usual standard of the Samuda design. The linear valve was a series of leather flaps attached to one side of the slot with a series of iron covers over them to reduce exposure to weather. The train was pulled up atmospherically, but it went back down by gravity, controlled by brakes. Trains varied in length based on demand, with unneeded cars stored on the track north of the platform at Kingstown. The practical limit of the atmospheric pipe proved to be nine loaded cars, seventy tons, a weight at which the train barely made it up the final grade into Dalkey station.

In 1899 an old man recalled riding on the Dalkey line as a boy. There was no telegraph between the terminals, so the engine was always started up on the timetable with no knowledge whether the train at Kingstown was ready. People at Kingstown could tell when the engine had started by the whoosh of air being sucked into the end of the pipe. When the brakes were released the train rolled forward down a slight grade, sometimes assisted with a human push, and once the piston went into the pipe the train probably could not stop. A man in the engine house at Dalkey would go up the tower and look for the train coming, and when he saw it he would shout to the engineer to shut off steam. The train was expected to shoot out of the tube and glide up into the station by momentum. On some occasions power was shut off too soon, and young men among the passengers were asked to assist in pushing the train the rest of the way, no doubt impressing ladies on board. On two occasions the old man knew of, the train ran in too fast and went right through the station. On the trip back to Kingstown, gravity on the one per cent grade was sometimes not enough to overcome gusts of wind in the cut, and the train would stall waiting for the wind to subside. The trip down was always slower than the powered trip up. (This account is in Howard Clayton's book.)

A significant source of ridership was from tourists going to see the unusual railway. Whether that was enough to pay its way has been disputed, but because the Dublin to Kingstown segment was quite profitable, and the passengers for the Dalkey branch increased income there, it might be considered as paying for itself indirectly. Aside from the mechanical complications of the atmospheric system, and the improved performance of locomotives during the next ten years, the main reason for discontinuing the atmospheric system was a plan to extend railway services farther south. It made no sense to operate one intermediate section in a different way.

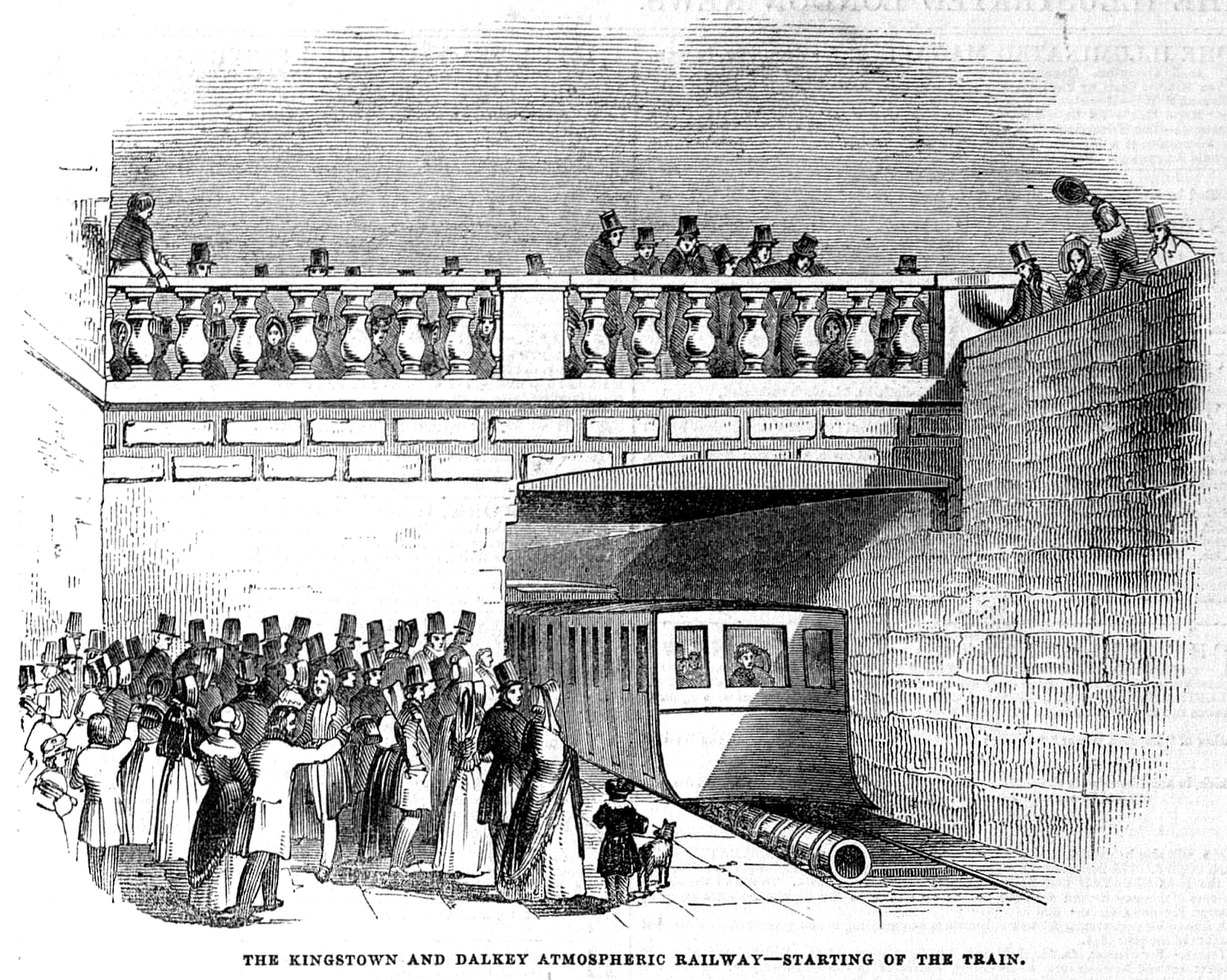

— The Kingstown and Dalkey Atmospheric Railway— Starting of the Train, by James Mahony, Illustrated London News, 6 January 1844.

At its opening the Illustrated London News called the Dalkey branch "this triumph of science." The accompanying illustration of the Kingstown platform provides some detail. The "leading carriage" to which the piston was attached is not in sight, because it remained at the Dalkey end at all times, giving the "conductor" no view ahead when he let the train down with the brake, but it would not be hard for him to recognize the short tunnel just before it entered Kingstown. The pipe at this end was left open, since normal pressure behind the ascending train was exactly what was needed.

In Charles Hadfield's book is a photograph of the same scene in 1955, when there was still only one track leading south, and what appears to be the same railing is in place overhead. I was able to photograph a scene at almost the same location, below. The second track was added to the right.

— Dún Laoghaire Mallin station, looking south, 2018.

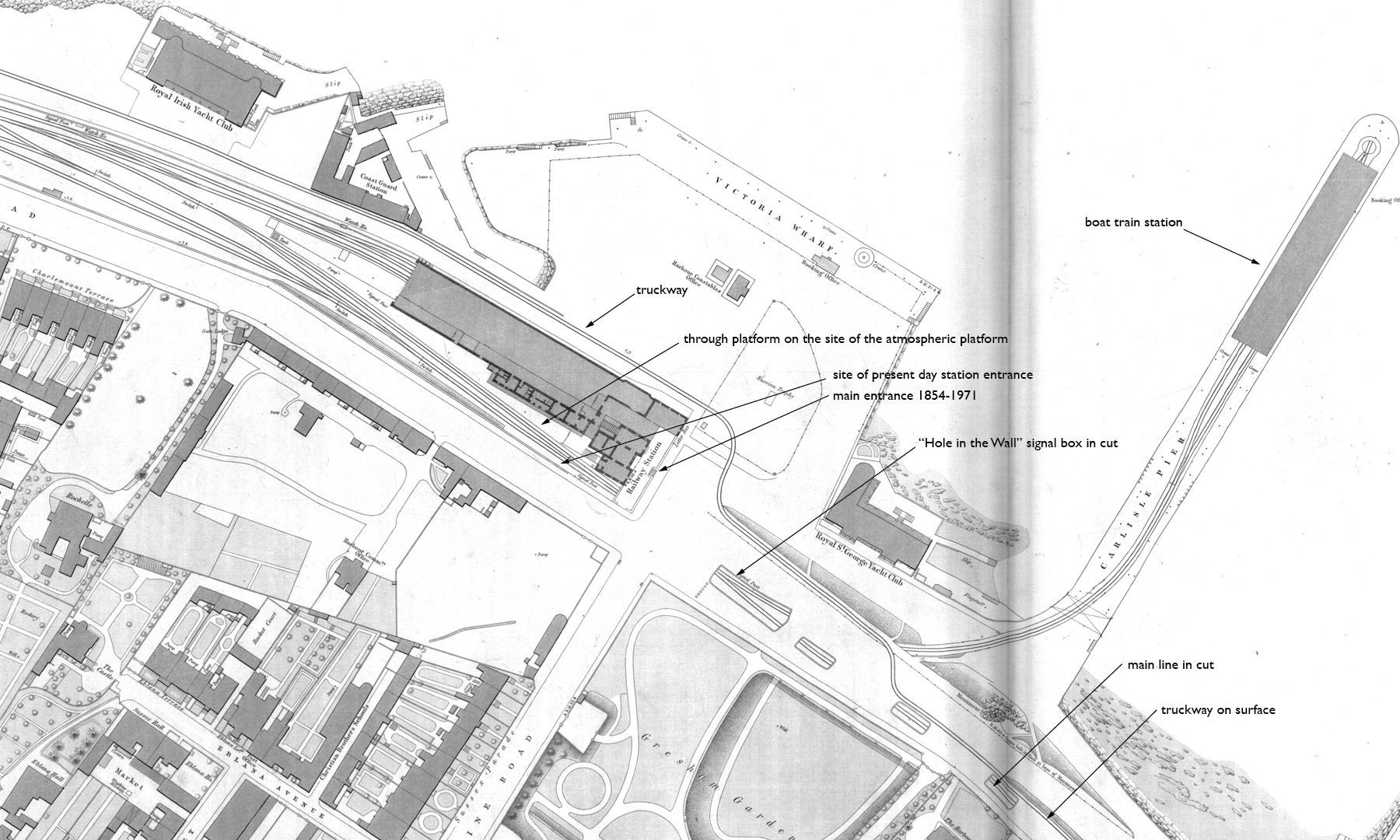

The station house was replaced in 1854 with the large structure of classical design that is there today but no longer serving as the station house. The cut for the atmospheric railway was improved for locomotive trains in 1856, and it was widened for two tracks in 1882 except at the station. Until 1957 there was just one through track with a platform on the site of the atmospheric platform, which had to serve trains in both directions, and one other terminal track with a platform for local trains to Dublin.

The map above shows the new station arrangements but pre-dates the double track in the cut (lower right). The single track bottleneck for almost a century was in the tunnel between the through platform and the Hole in the Wall signal box, where a siding led to Carlisle Pier for boat trains, including boats carrying Royal Mail to Britain.

The atmospheric railway did not replace the old truckway, which was simply realigned as need be to avoid the open cut, even as changes were made. Not only was the truckway kept open as a public footpath, but even the track was maintained into the early twentieth century, for use by people who had carts that would fit. Right around Dún Laoghaire station remains of the truckway are scarce, but from People's Park to the Quarry it can be traced today as a public footpath known by its traditional name The Metals, as described in great detail in Rob Goodbody's book The Metals.

For more on the history of the harbor, with many old maps, see Dún Laoghaire Harbour Heritage Management Plan, November 2011

— Kingstown station of 1845, front, 2018.

It's easy to visit Dún Laoghaire and Dalkey on the same day. They are just a few stations apart by DART train, and you will be riding on the route of the atmospheric railway, or almost.

My description of the atmospheric railway between Dún Laoghaire (Kingstown) and Dalkey continues on the Dalkey page.

— DART train, access to next carriage, 2018.

— Iron Road Erin logo, 2018. Mainline trains are also available between Dublin Pearse and Dún Laoghaire Mallin.