Extra

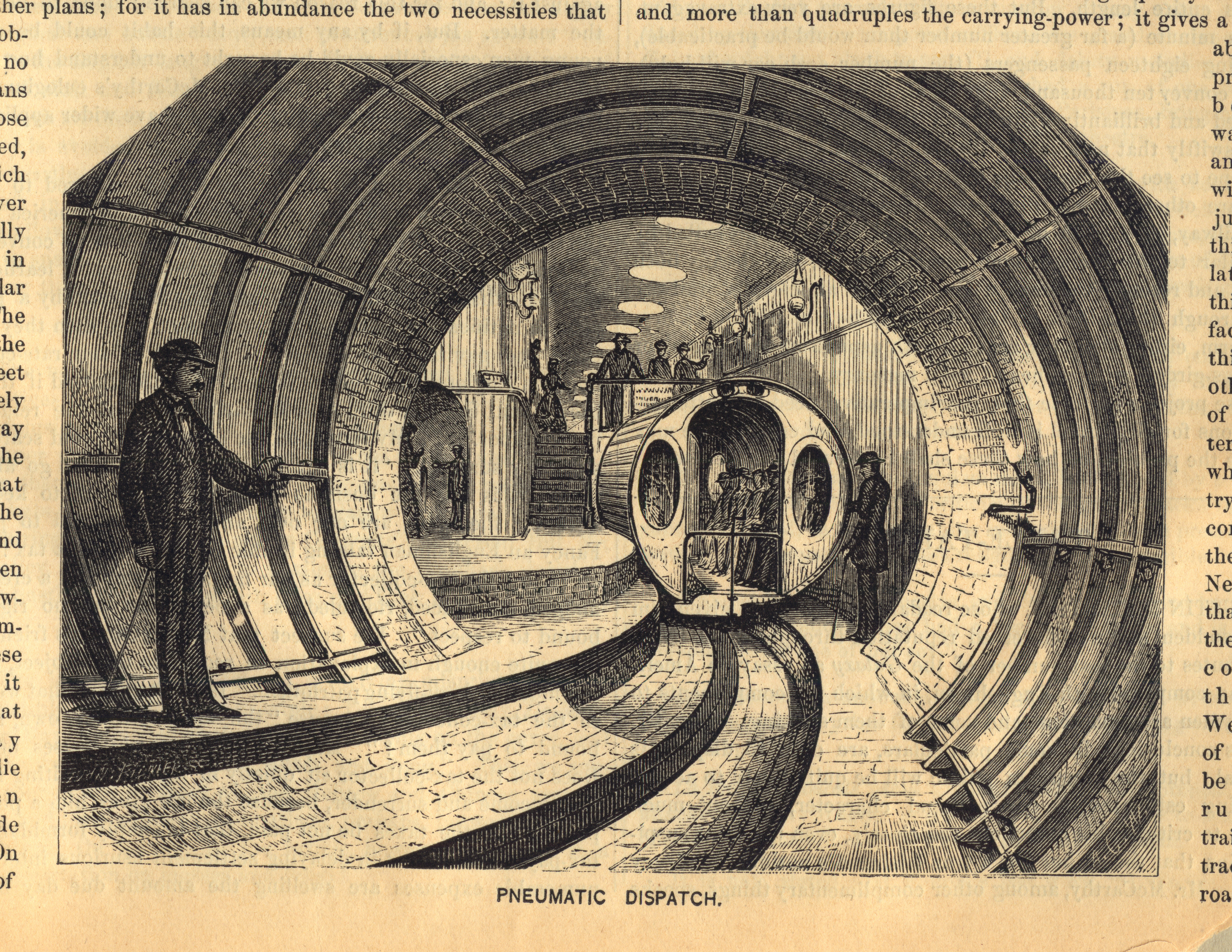

Pneumatic Experiments

In which Joe visits unmarked historical sites where there is nothing left to see.

In this chapter I will review the experimental cousins of the atmospheric railway, in which the entire vehicle is in the tube. The first of this type, built by John Vallance, was already described, because it led to the atmospheric railways..

George Medhurst.

George Medhurst published a pamphlet called A New Method of Conveying Letters and Goods with Great Certainty and Rapidity by Air in 1810, and two years later in Calculations and Remarks Tending to Prove the Practicability, Effects, and Advantages of a Plan for the Rapid Conveyance of Goods and Passengers upon an Iron Road through a Tube of 30 Feet in Area, by the Power and Velocity of Air he dared to suggest using the same method with vehicles large enough for passengers and freight. He never built a demonstration. That was left to John Vallance in 1824. Vallance's method reduced pressure ahead of the carriage, making the power literally "atmospheric" in nature, but that name became dedicated to systems that had a piston in a tube and what Vallance called a "super-terraneous" train.

Medhurst's last words on the subject were published the year he died, 1827. In his succinctly entitled A New System of Inland Conveyance, for Goods and Passengers, Capable of Being Extended throughout the Country, and of Conveying all Kinds of Goods, Cattle, and Passengers with the Velocity of Sixty Miles in an Hour, at an Expense that will not Exceed the One-fourth Part of the Present Mode of Travelling, without the Aid of Horses or Any Animal Power, he proposed the method of vehicles connected to a piston in a small tube, but like his previous proposals it involved increased pressure behind the piston. Vallance never changed his view, writing in 1842 to the The Mechanics' Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazett that while "I am aware that I stand alone in this belief" he thought placing the trains in the tube would be simpler and more reliable than a system using a linear valve. Later developments proved him correct.

After the Croydon and South Devon atmospheric operations ended in 1848 and no one wanted to talk further about it, a decent interval went by, and then Medhurst's idea of using air pressure in small tubes, for letters and packages, crept back into inventors' minds.

Josiah Latimer Clark and Thomas Webster Rammell.

In 1853 the Electric and International Telegraph Company began experiments with pneumatic tubes over short distances. Josiah Latimer Clark built the company a 1½-inch tube to carry printed telegraph messages over the proverbial last mile, actually just 675 feet, to the London stock exchange. Traders were willing to pay for every advantage in getting the latest news. The company tried to interest the Post Office in using a similar system between post offices in London, but were told that the price asked was too high.

In 1859 Latimer Clark and another inventor, Thomas Webster Rammell, formed the London Pneumatic Despatch Company to develop a system of small railways running in tubes by pneumatic power. Rammell's patent of 1860 described it:

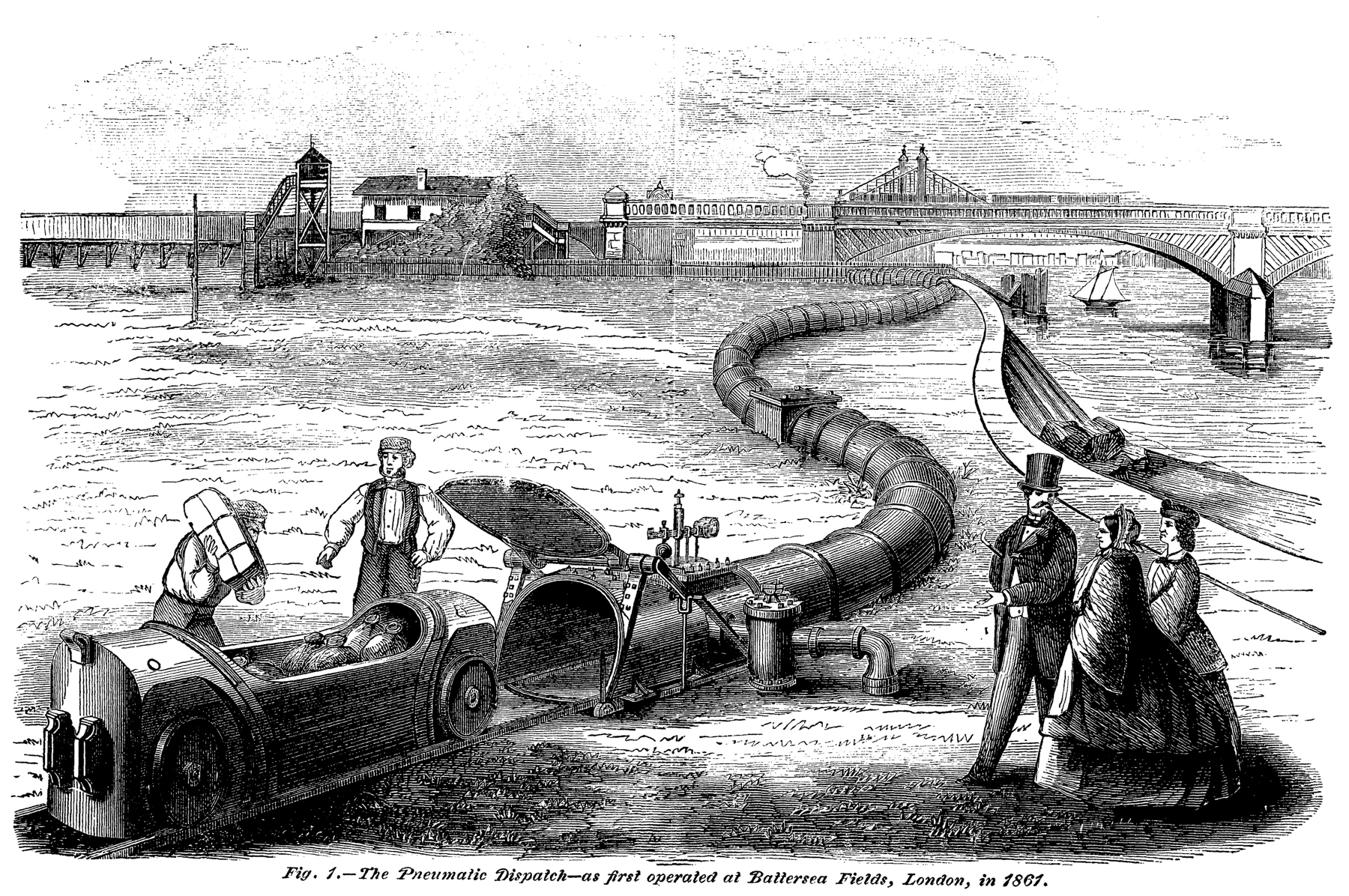

This invention is for an improved pneumatic railway peculiarly adapted for underground communication in large towns, but which may be applied above ground, and be used even for country lines. The railway is placed in a hollow way or tunnel, which may be of any shape, but will be most conveniently made of the same shape in transverse section as the carriages employed, and in size very little larger than such carriages. The carriages are entirely supported, and in their motion directed by, the iron rails, grooves, or trams constituting the way.... The pneumatic pressure is applied over the entire transverse area of the carriages, either by exhaustion or compression.... The railways may be used for the conveyance of passengers or goods, or upon a smaller scale of any size desired, for the conveyance of parcels and letters, in which case the rails or grooves guiding and directing the motion of the carriage may or may not be part of the body of the tube, as so desired.This described more than a dispatch system for letters and parcels, but the partners decided to start small. They constructed a prototype with a two-foot gauge track running in thirty-inch tubes on open ground at Battersea in 1861. While the Battersea cars were certainly meant only to carry packages, some people volunteered to make the trip. "They lay on their backs, on mattresses, with horsecloth for coverings."

The location was not Battersea Park, but the grounds just east of the Grosvenor Railway Bridge where the well-known power station was built later. Below, the scene in 1861 and today. Compare the railway bridge (which is wider now than it was then) and the towers of Chelsea Bridge just beyond it.

— "The Pneumatic Dispatch—as first operated at Battersea Fields, London, in 1861", via Beach, Pneumatic Dispatch, 1870.

— The same location, October 14, 2018.

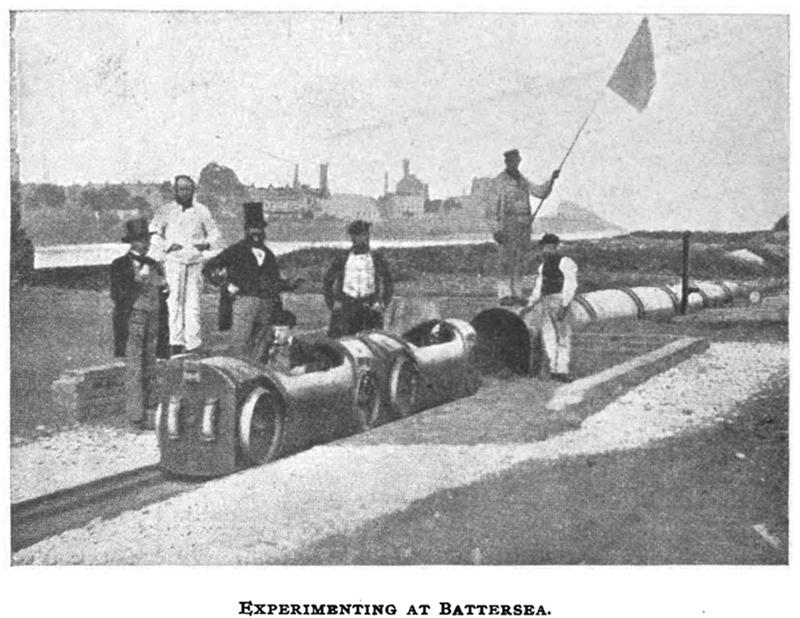

The picture below is of low quality, but I want to show it for the rarity of a photograph of the scene in 1861. We can see a gentleman who has taken the ride, and a man who is probably signalling to the engine house. My own view back to London from roughly the same spot does not seem to show any landmark in common. At the dock is the Transport for London riverboat that I rode from Embankment Pier on a rainy day.

— "Experimenting at Battersea." Compressed Air, May 1900.

— The same location, October 14, 2018.

The company frugally reused the cars and tubes for their first application in 1863, a tunnel from Euston railway terminus to the North Western District Post Office. Two of the cars were salvaged from that tube in 1930. I saw one in 2000 at the National Railway Museum in York and another in 2018 at the Postal Museum in London. Seen below, aside from the loss of the rubber fittings and a rust hole, it is one of the Battersea cars.

— Battersea pneumatic car, Postal Museum, London, June 28, 2018.

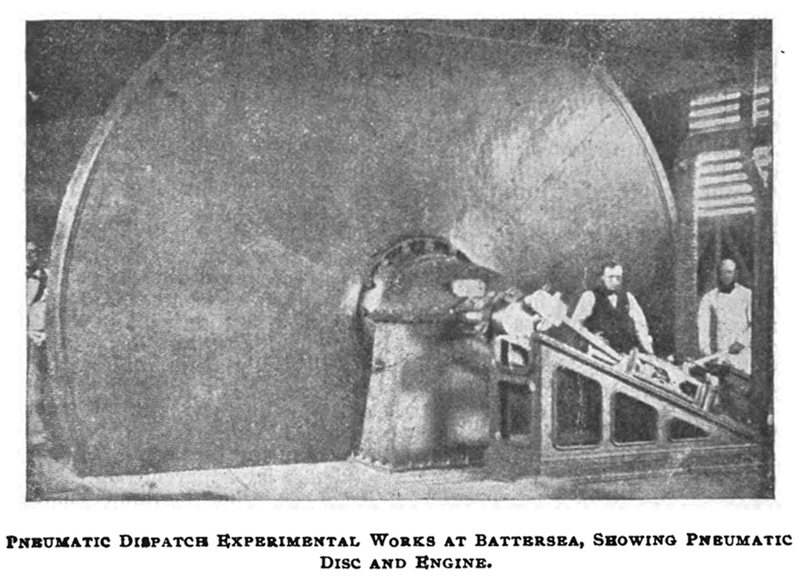

The vacuum for the atmospheric railways was created by pumps, but Rammell chose to use a gigantic flywheel. Twenty-one feet in diameter, it was made up of two iron disks between which was a spoked wheel with "thirty-two V-shaped cavities". This is again a rare photograph that I will use despite the poor reproduction.

— "Pneumatic Dispatch Experimental Works at Battersea, Showing Pneumatic Disc and Engine." Compressed Air, May 1900.

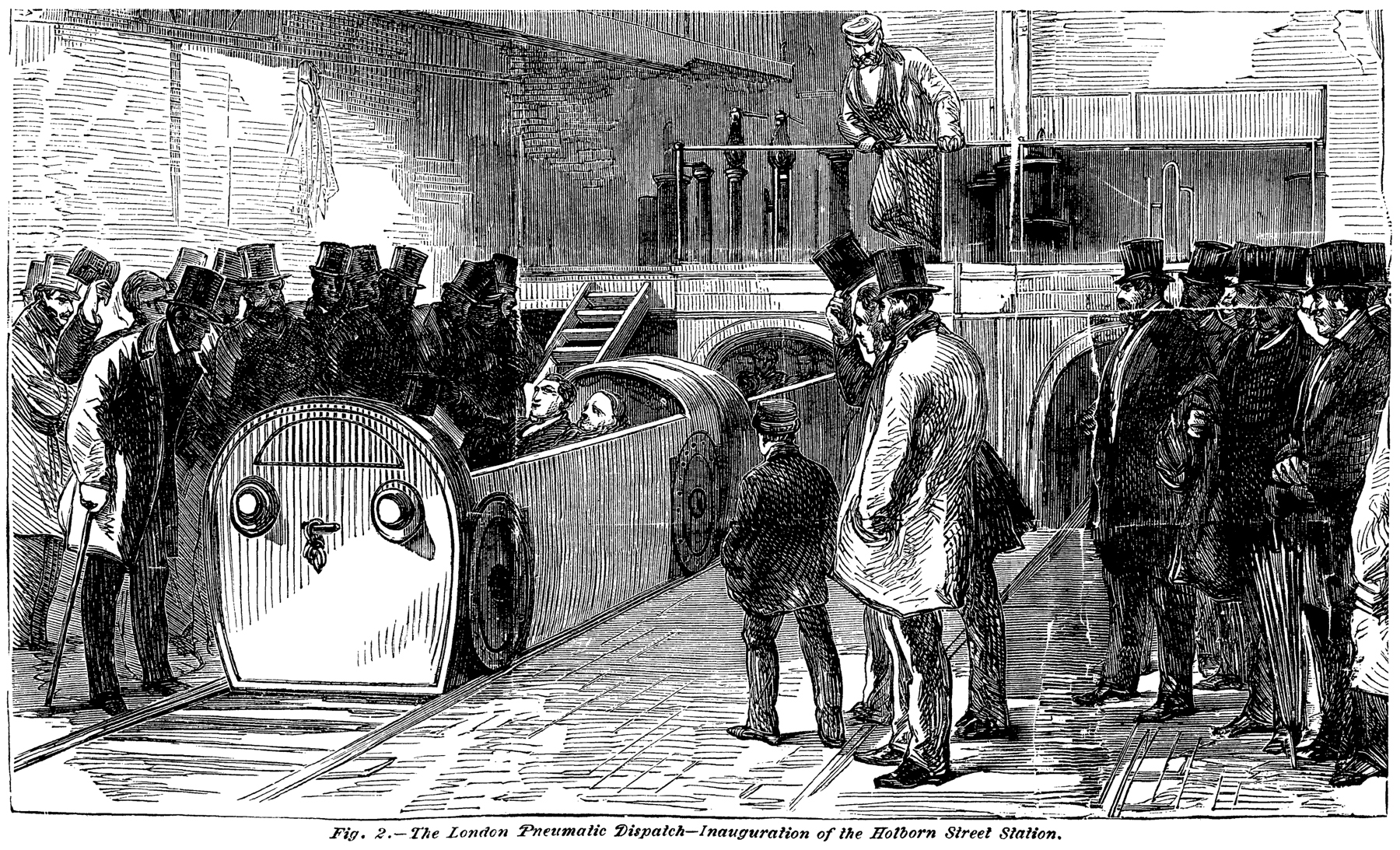

The London Pneumatic Despatch Company built two lines of tubes from Euston that were in use from 1863 to 1874. Below, the partial completion of the second tube in 1865 was celebrated with another round of informal passenger service.

— "The London Pneumatic Dispatch—Inauguration of the Holborn Street Station", via Beach, Pneumatic Dispatch, 1870.

The Post Office called an end to the service. One reason given in some accounts was simply that the company's charges exceeded the benefit, but there are also accounts of cars stuck in the tunnel that had to be pulled out with ropes, and water damage to the mail from leaks.

Thomas Webster Rammell.

While the Pneumatic Despatch Company was still in operation, Rammell moved on to promoting passenger railways. This called for a larger and more impressive demonstration, and so he arranged to build one on the grounds of the very popular Crystal Palace in South London. He wanted to get everyone talking.

The "Penge and Sydenham Railway" was confined in something like a tunnel that was actually the "hollow way" mentioned in Rammell's patent. The lower part was within an excavation about four feet deep, and the upper part was within a brick arch covered with earth. It was 600 feet long, with an elliptical interior nine or ten feet high by eight or nine wide, and it was not simply level and straight, but had a grade at some point of 1:15 a curve of eight chains radius. The engine house was outdoors: a rented steam locomotive lifted onto a brick base, powering a disk wheel of 22 feet diameter at up to 300 rpm, creating a pressure of 2½ ounces per square inch. The carriage was pushed by air pressure behind it to the far end, where there was a vent open to normal atmosphere, and pulled by reduced pressure in front of it for the return.

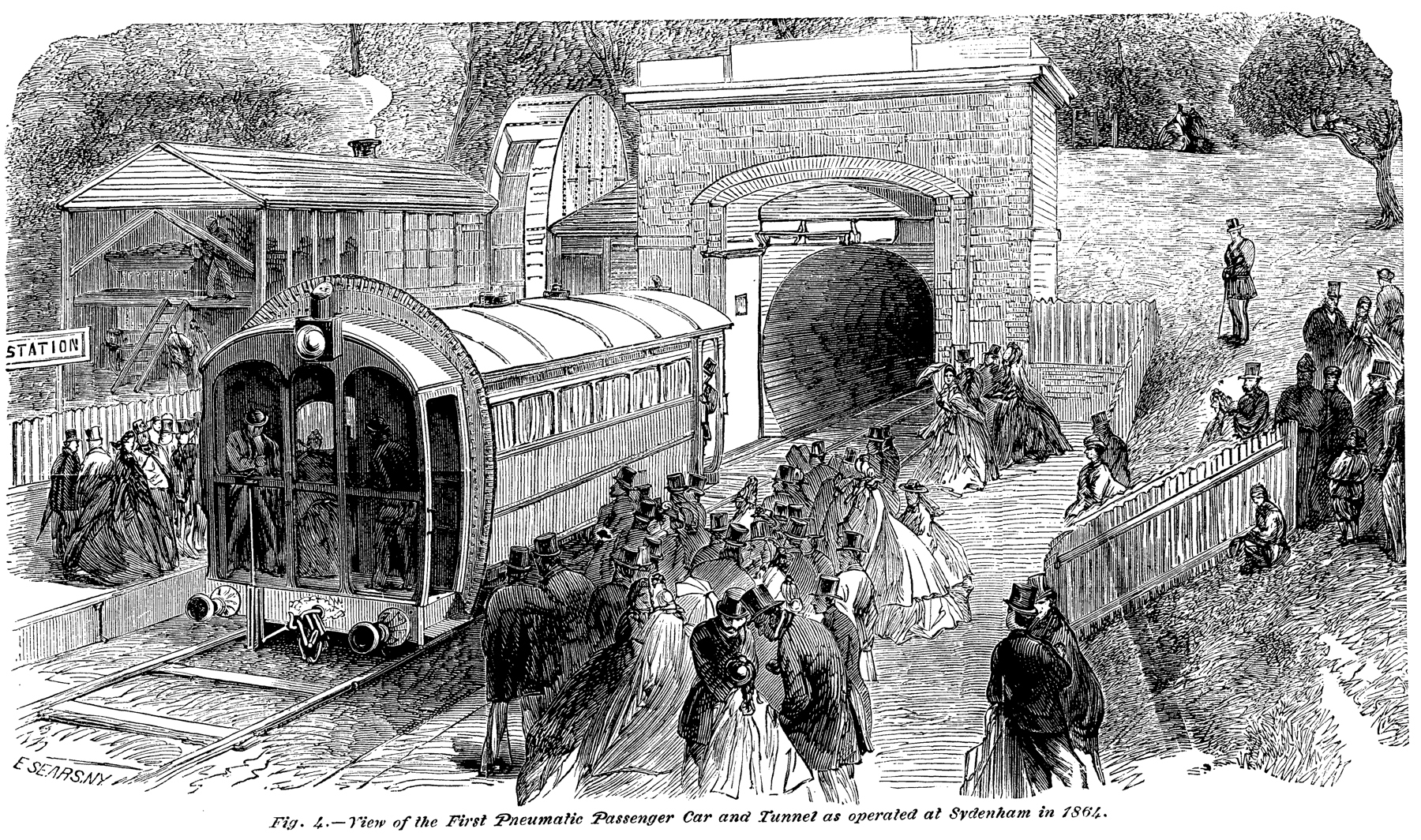

The illustration below gives the impression that the railway went into a hill, but it did not. The entrance was actually at the highest point. The steam locomotive is somewhat visible on the left side. The rotating disk was probably not this thick. Notice the brush collar on the car. The car rolled down a slight grade into the opening, and then the door closed behind it, allowing air pressure to do the rest. It was what modern-day park operators would call a "dark ride", and although there were some gas lights inside, the closeness of the walls would give the thrill of high speed.

— "View of the First Pneumatic Passenger Car and Tunnel as operated at Sydenham in 1864", via Beach, Pneumatic Dispatch, 1870.

Rammell spent eight months and a few thousand pounds on the installation, which was open only for two months, from August 29 to October 31, 1864. Then, as agreed, he had to remove everything and restore the park to its previous condition. As a result of that and later changes, nothing is visible today.

The best description of the location may be found in the Illustrated London News for September 10, 1864. "It extends from the Sydenham entrance to the armoury, near the Penge gate, a distance of nearly six hundred yards." After many later years of speculation, the path of the railway was was determined in 1989 and is described by Roger J. Morgan at Xenophon.org. The bottom 1.5 meters of the "tunnel" were left in place after it closed and covered with brick rubble, cement, and earth, sufficient to restore the surface. But that lowest level made much of it detectable by remote sensing from the air. A small section was opened up in 1989, revealing the brick invert with longitudinal pine sleepers spaced for standard gauge track and a central drain channel.

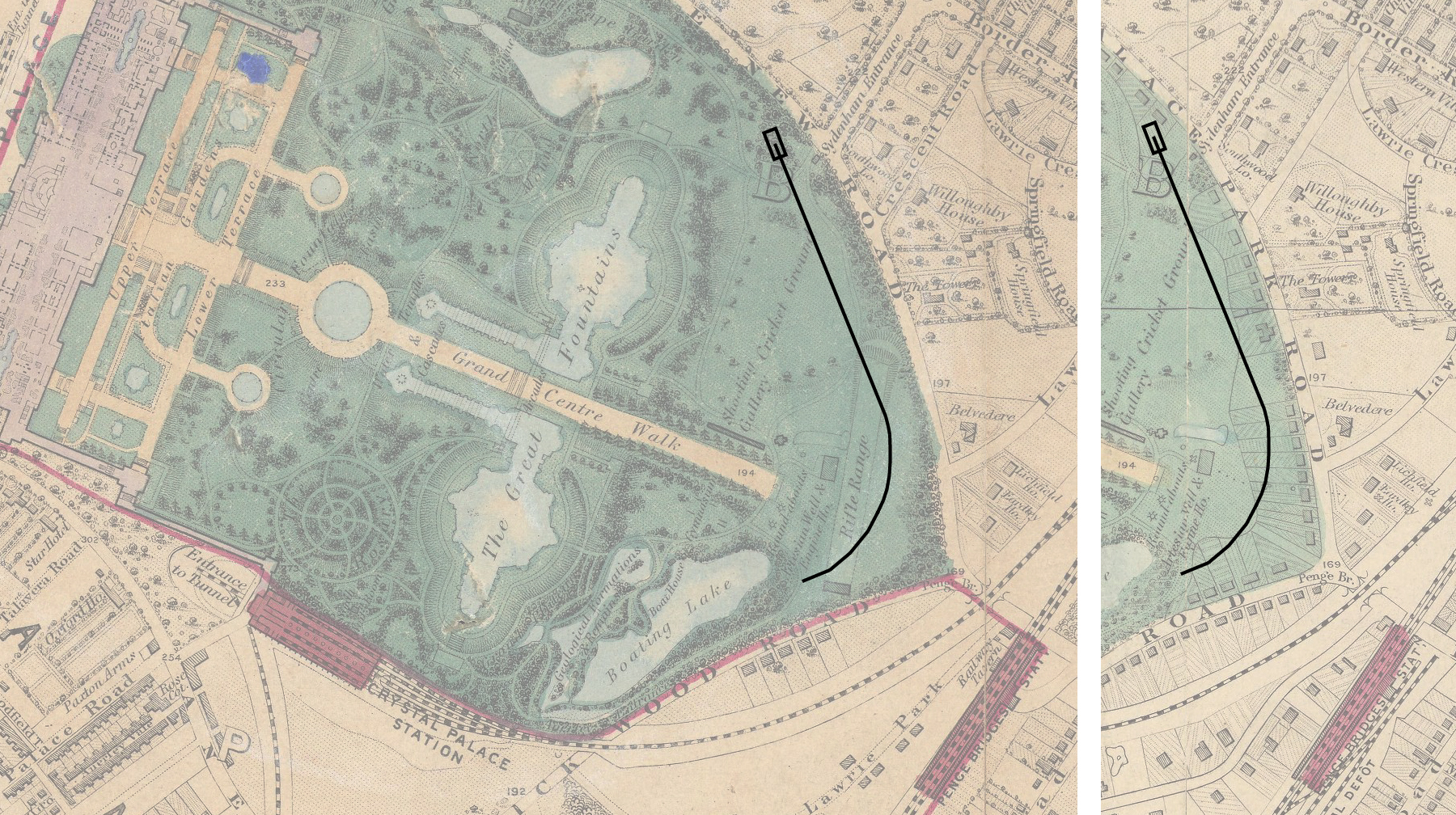

The maps below are based on Morgan's analysis of LIDAR (remote sensing) data from UK government sources. The long straight line from Sydenham gate is clear in the sensing most of the way, but understanding what the line represents depended on separate research about the pneumatic railway. The curve is less obvious in the sensing, but it is the part deepest below the surface. Morgan was also able to create a gradient profile, for which you should see the Xenophon page. The lowest point was under the Centre Walk, and the 1:15 went up from there to the end, giving car a boost in starting the return journey.

— Stanford, map of London, 1866 (left) and 1886. Lines added by Joseph Brennan, based on Roger J. Morgan's map at Xenophon.org.

Near the bottom, the Boating Lake and Geological Formations are the site of the famous dinosaur figures.

The "armoury" is on the earlier map at the southern end of the Rifle Range, which was built in 1861 but never approved. It left its mark by an earth mound that was the butt behind the targets, and not anything to do with the railway tunnel as sometimes thought. The path from the Penge gate to the Grand Centre Walk would have passed through the rifle fire. The most noticeable change by 1886 was the construction of houses along the margin of the park with their back gardens built unknowingly over the abandoned railway line. Some of these were later removed.

The grounds at Sydenham gate around the station and tunnel entrance are now occupied by a house and a parking lot. My photograph below looks up hill, on approximately the line of the tunnel, parallel to the footpath on the left.

— Crystal Palace Park, October 9, 2018.

Following the popular success of the Crystal Palace railway, Rammell formed the Waterloo and Whitehall Railway in July 1865, together with directors of the London and South Western Railway. The single track was to run for just over half a mile crossing under the Thames from the L&SWR's Waterloo terminus to Great Scotland Yard, near Charing Cross. Rammell planned to run three-car trains six minutes apart on a journey of two minutes.

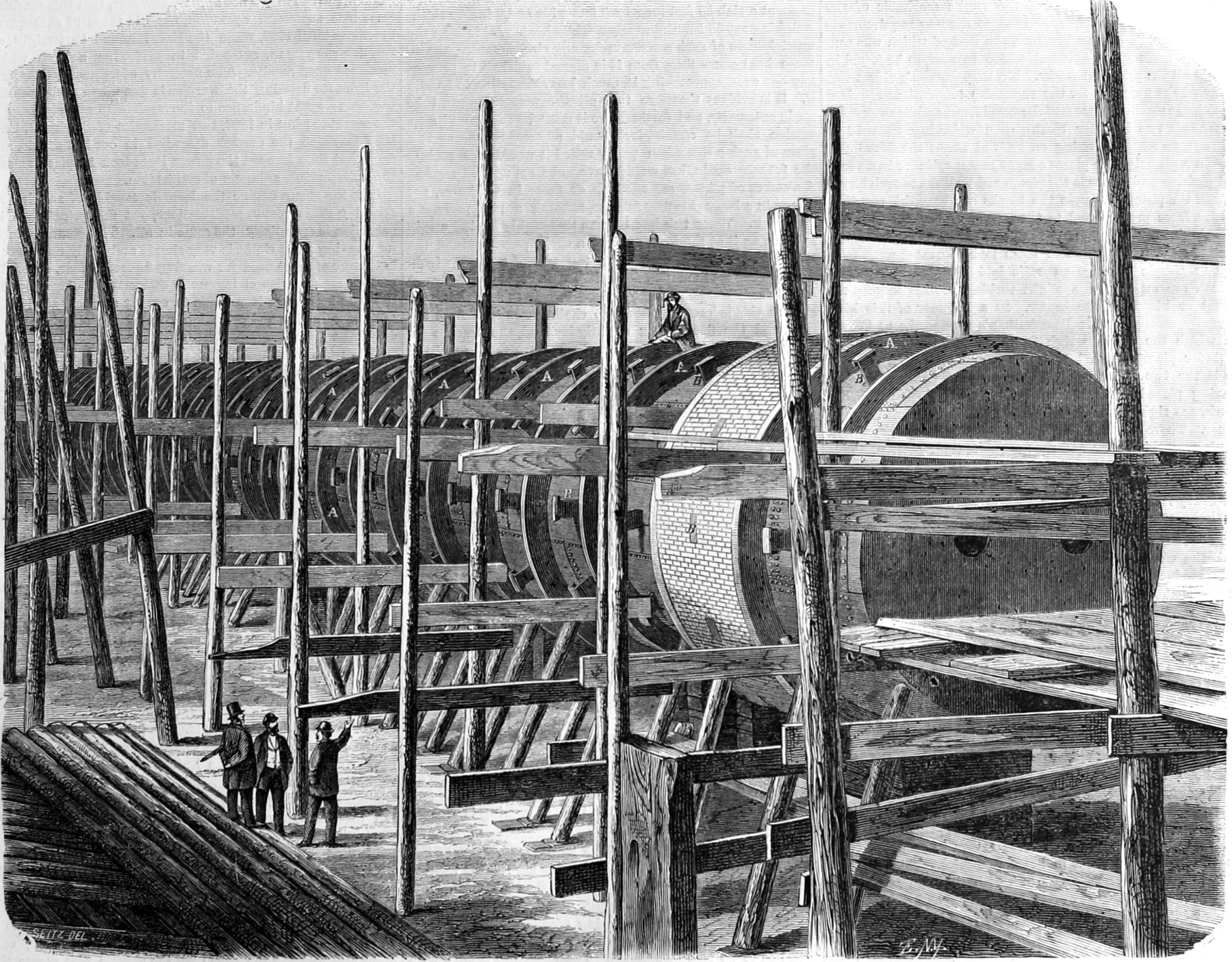

The section crossing under the river was to be a tubular bridge with its top just twelve feet below low water in the tidal Thames. Four iron tubes 240 feet long, encased in three rings of brick, would rest on three piers in the river built on solid clay and on abutments on each bank. Under land at each end were to be brick tunnels built on a 3 per cent grade so that gravity would assist starting and braking. The engine house, at one end only, would use a 40-foot diameter centrifugal fan similar in design to the smaller ones Rammell used at Battersea and Crystal Palace.

Work began in October 1865. The tubes were made at the Samuda ship yard— their last involvement with air-powered railways. Three of the tubes were built but none was installed. The Panic of 1866, which delayed completion of the second Post Office tube, had an even worse effect on the Waterloo and Whitehall. Work never resumed. One of the tubes is shown below.

— Scientific American, March 16, 1867.

The company's engineer Edmund Wragge recalled in 1902 what was built: the crossing under the Embankment, a short length of tunnel under College Street (south bank), and the foundations of two piers closer to the south bank. Some say that the tunnel came a little further up Great Scotland Yard than the Embankment and was made into a wine cellar for the National Liberal Club. Wragge commented also on a depression in the river found during construction of the Bakerloo tube, which he thought might have been from removal of one of the piers.

It is important to notice that Rammell proposed pneumatic transport only for special cases like a short railway in a tunnel under a river.

By 1865 many people expressed concern about the air in the tunnels of the Metropolitan Railway, a problem that the company was already trying to improve in new construction by using more sections of open cut. The failure of the Whitehall and Waterloo was a question of financial markets rather than its technology. But if it had been completed, using the same method for a railway of longer distance and with intermediate stations remained untested. I don't think even upon success that the Waterloo and Whitehall would have stopped the use elsewhere of locomotives and then electrical power.

Alfred Ely Beach.

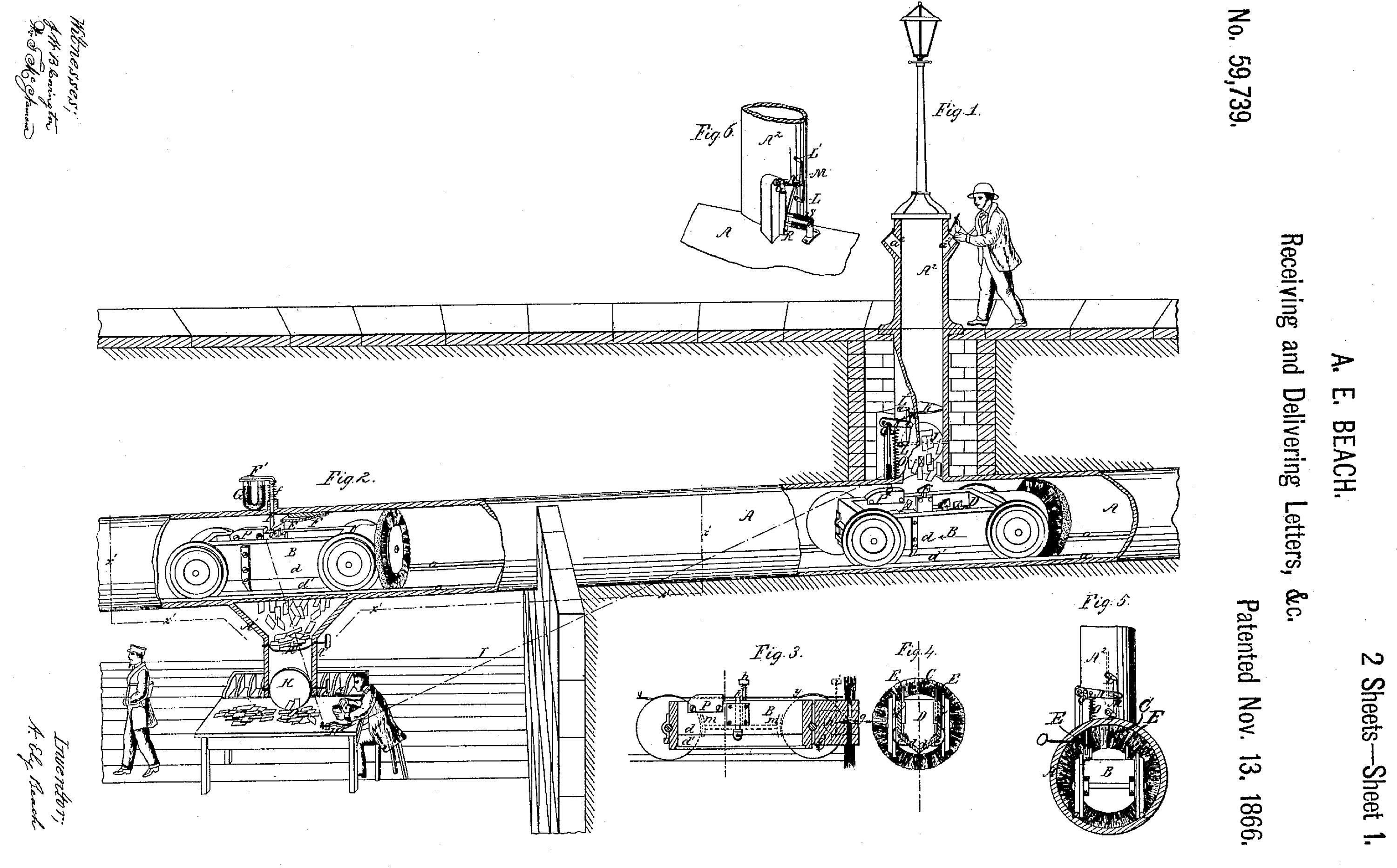

Across the Atlantic, Alfred Ely Beach, a busy patent attorney and an editor of Scientific American, tried to work out improvements to mail and package delivery with a system of underground tubes. His first patented method, 1865, showed a chain drive in the tubes, but the second one a year later has a pneumatic tube, to which anyone could introduce a letter by dropping it into a special hollow lamppost, where it would lie at the bottom until a pneumatic car came by that would open the trapdoor and collect it, and then deliver it to a post office. The little cars had a brush collar similar to that of the Sydenham car.

— United States patent 59,739.

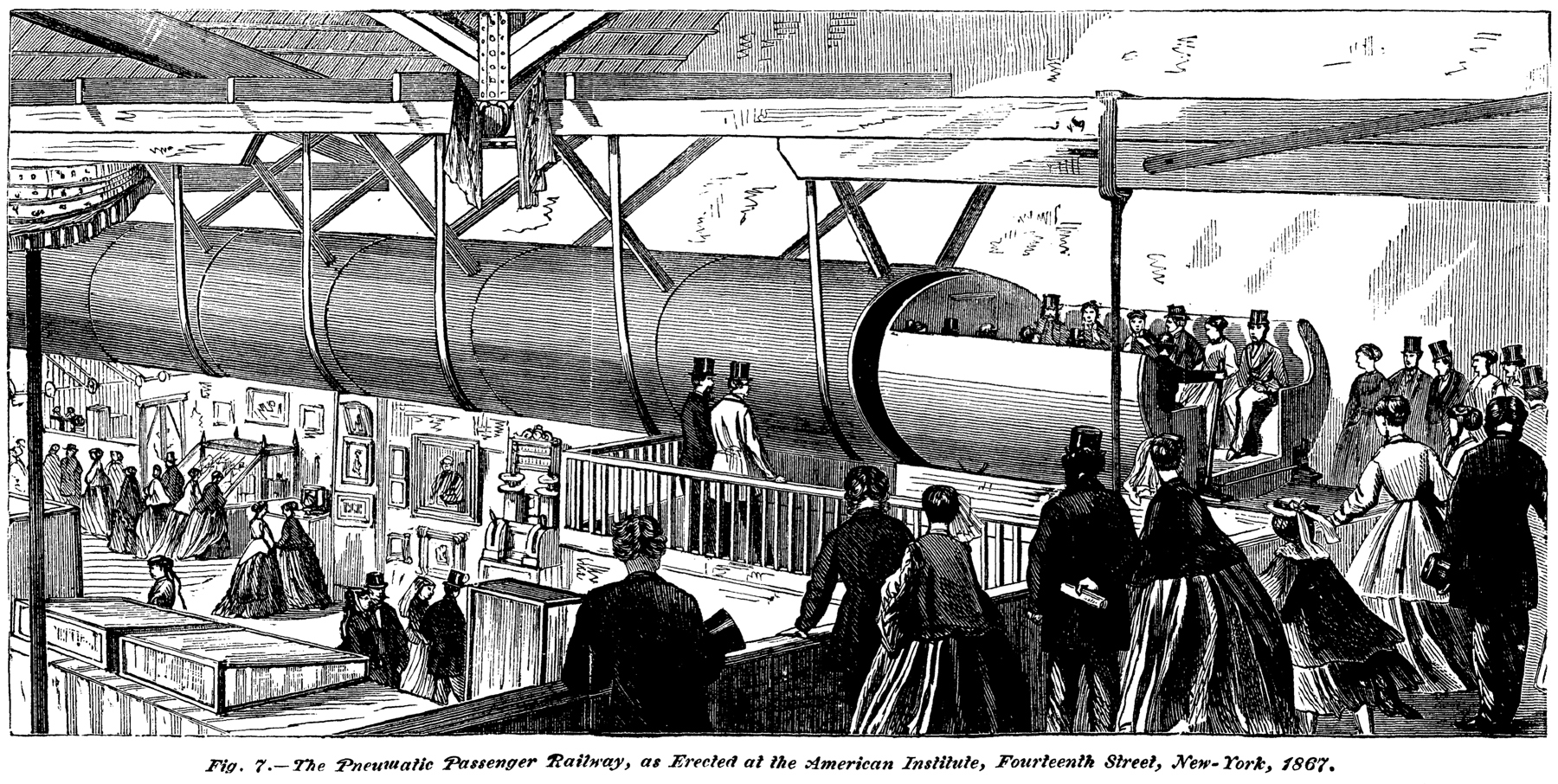

In 1867 Beach became the president of new companies in New York and New Jersey that proposed to build a long-distance pneumatic tube for mail and packages, starting with a tunnel under the Hudson. That year at the annual fair of the American Institute he presented an atmospheric tube that carried passengers across the large exhibiton hall, about 200 feet. This was the first American demonstration of a pneumatic railway, much shorter than that at Sydenham, but, like it, attracting the attention of potential investors in the nation's largest city.

— "The Pneumatic Passenger Railway, as Erected at the American Institute, Fourteenth Street, New-York, 1867," via Beach, Pneumatic Dispatch, 1870.

Before other construction the company was required to complete a tube of about two miles from the city's main post office in Nassau Street. The future looked bad when the Postmaster refused to cooperate, but at the end of 1868 Beach leased the basement of 260 Broadway, from which his company began construction in 1869 through a hole in the wall and out under the street. The excavation was about a foot larger than permitted, to allow for the thickness of the wall around a finished tube of the permitted size. If I may contradict what has been written later, the small tube was actually built, although to what distance is uncertain. Newspaper reporters in 1870 and 1886 wrote that they saw the tube.

The tube would have been useless unless the Postmaster changed his mind or the company's Act was amended. Beach achieved the latter at Albany in 1869. The new Act described various changes in wording of the original Act. It was obvious that cooperation from the Postmaster was no longer required. It was not obvious that the change to another sentence omitted the clause providing for regulatory inspection of work in progress! Given the latter change, Beach stopped work on the first tunnel. The plan now was to build a much larger tunnel to contain within it two of the 54-inch tubes that were still required. One might argue that this method of construction was in compliance, but Beach did not want anyone on site to say that it was not.

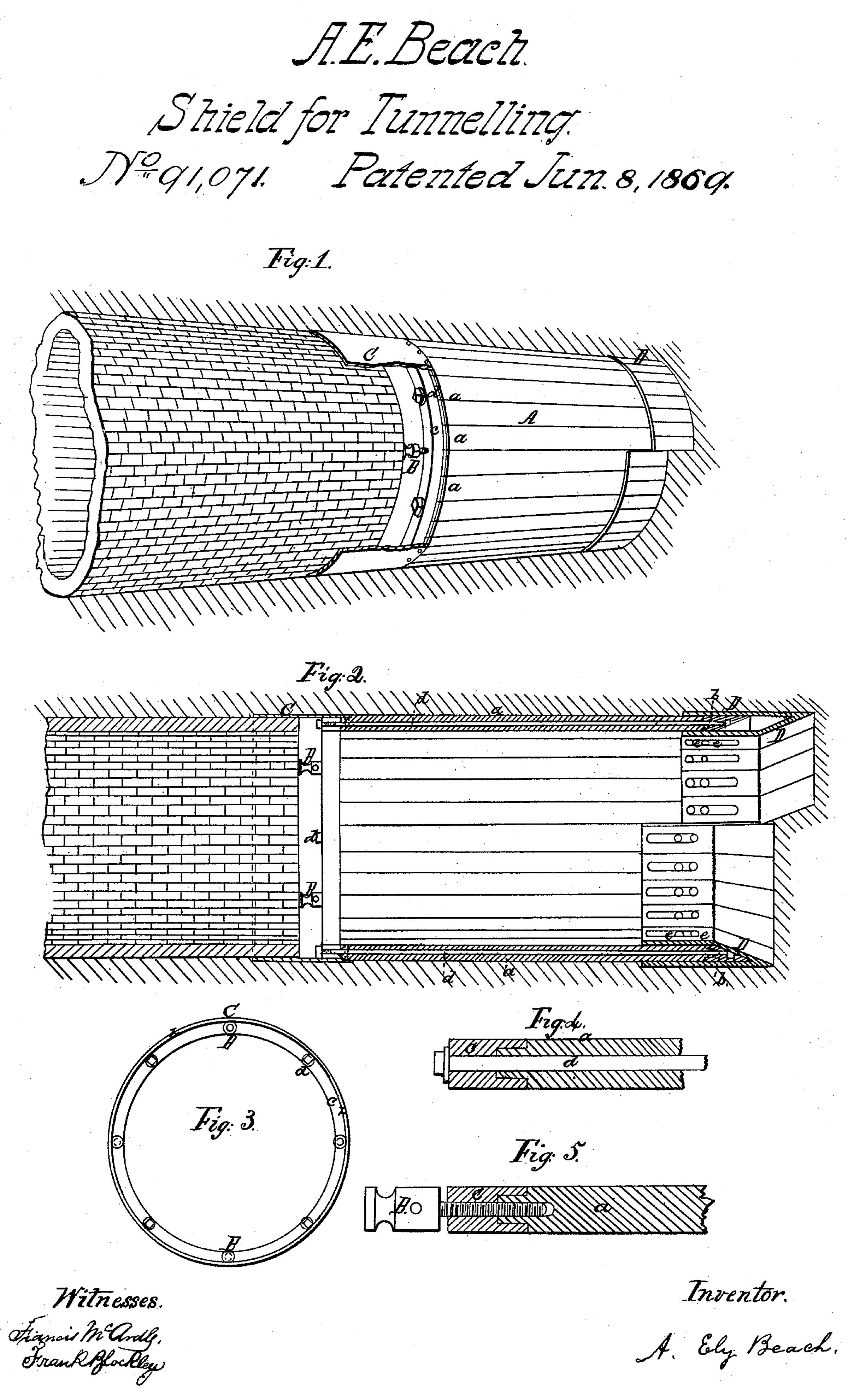

Rammell and Beach had already demonstrated pneumatic propulsion. Beach had two things to add. During 1869 he contracted with the Roots Brothers company for a very large version of their patented blower, which was an impeller, not a fan as sometimes stated. In doing so he set aside using not only the rotating disk that Rammell had used but also his own patent blower used at the American Institute. Beach's other important goal was to show that tunnels could be built without disturbing the street or buildings along it, in order to overcome the objections of wealthy property owners. His patent describes improvements to the shield method pioneered by Marc Brunel in the Thames Tunnel, similar to those in Peter Barlow's English patents of 1864 and 1868. Beach's includes a cutting edge and a hood, and while both describe using screw jacks to advance, Beach actually used hydraulic rams to do so.

— United States patent 91,071.

The new tunnel was 9 feet 4 inches in diameter. Work started in July 1869. It ran out from another hole in the basement wall into a 90-degree curve to the right and then under the center line of Broadway for a total of about 300 feet (descriptions vary). The Roots blower was installed in the basement in December. The work was not a secret. Newspapers commented on the materials going in and out on Warren Street.

In January 1870 Joseph Dixon, Beach's main partner in the company, explained to the papers that "public inspection" of the works would soon be permitted, mentioning among other things the "waiting room"— waiting room? Beach had obviously decided to repeat his demonstration with passengers. In fact the size of the Roots blower was justified only for operating cars of the full diameter of the tunnel.

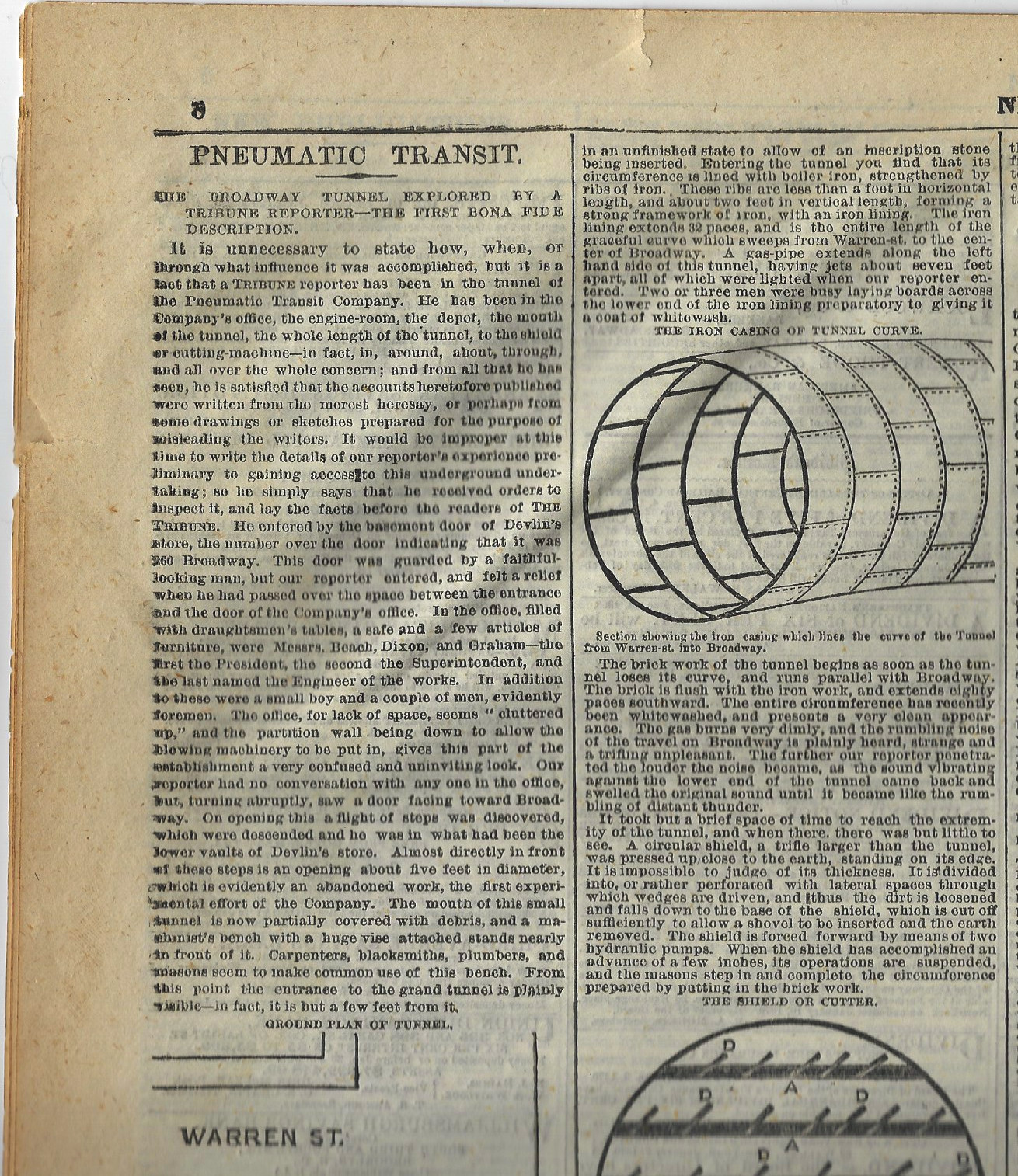

Days later the New York daily Tribune printed a lengthy article describing the premises, the reporter writing that it was "unncessary to state how" he gained admittance. Years later Beach's son said the reporter had come in disguised as a workman, but it is suspiciously full of details that read more like a press release. What people would want to read was an exposé of a secret tunnel. Beach was very good at publicity. The article, with numerous drawings, was on page 8, the back page, which would be visible to people who saw someone else holding up the paper while reading. Some of it is shown below. Notice the mention of the smaller first tube about five feet in diameter.

— New York Tribune, January 11, 1870. Brennan collection.

The official opening was on February 26, 1870, a Saturday, which guaranteed a story in the much-read Sunday papers. The tunnel was as much of a wonder as the method of propulsion, which was good because the car was not yet running but standing in the station, which was the carefully fitted-up basement.

With the blower at one end, operation was similar to the Sydenham demonstration, namely pushing the car out with increased air pressure behind, and then pulling it back with reduced pressure. There was a vent at the far end, near the tunnel shield, that came up in a grate in City Hall Park. (How Beach got approval for that has not been explained!). The greatest difference from Sydenham is that the public waiting room in the basement was part of the space subject to pressure changes. "A few grains of atmospheric pressure to the square inch are sufficient" to move the car, according to the Illustrated Description souvenir booklet, and no reporter ever mentioned feeling the pressure difference. Pictures show no enclosure near the tunnel entrance, and the same booklet also mentions that visitors pass through two doors to enter the waiting room, exactly what we today would call an air lock.

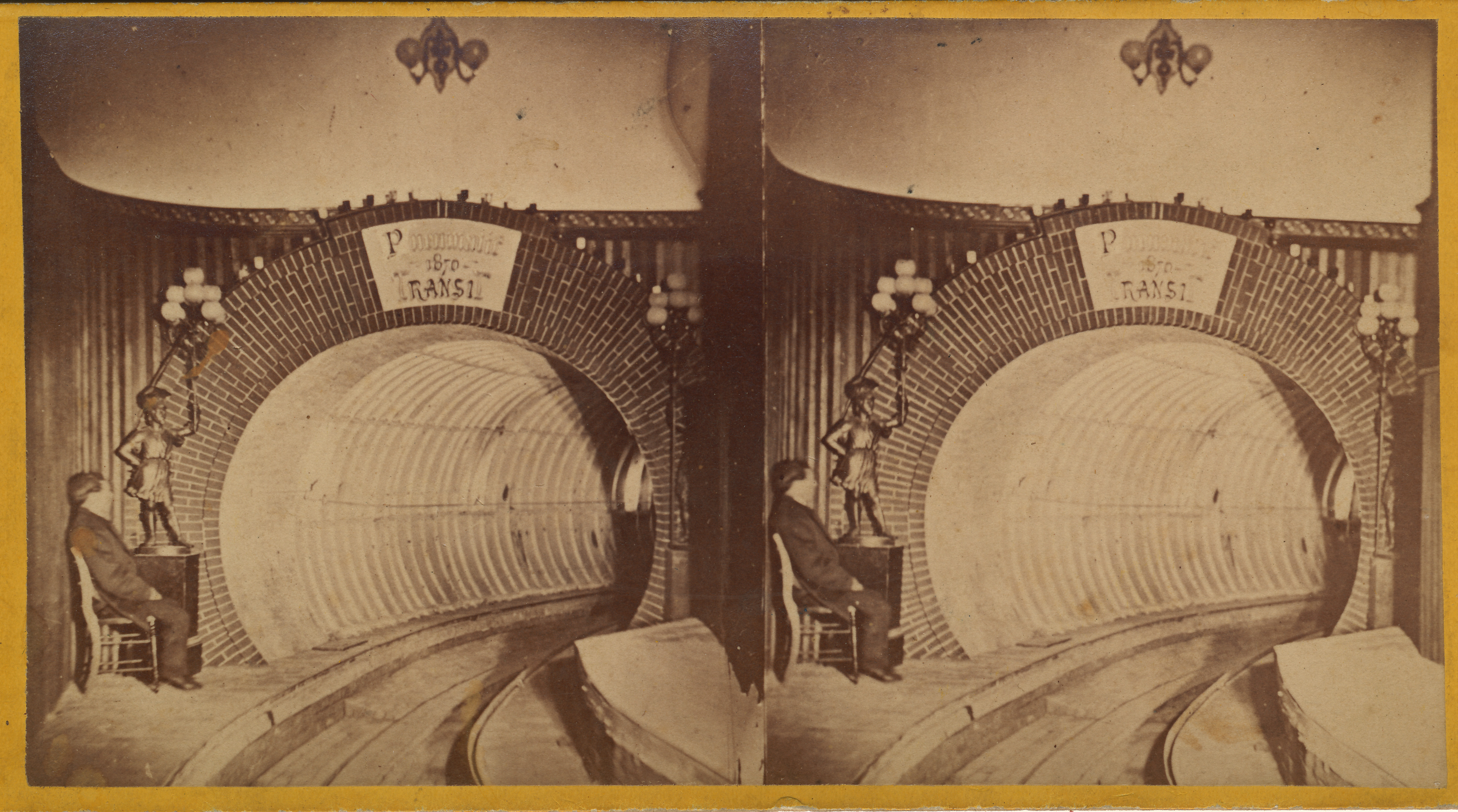

The stereo view that was soon made available shows the tunnel portal. The viewpoint is under the sidewalk of Warren Street looking toward Broadway. The curve in the wall on the left is the curve of the sidewalk at the corner. The keystone has the words Pneumatic / 1870 / TRANSIT, partially washed out by the photographer's limelight. The lumps over the arch were gaslights that glowed through glass of several colors. The light fixture at the top stands out in stereo as closer to us than portal. The wall was described as white-painted plaster over a carved wooden divider, below which were vertically laid strips of wood. The curved part of the tunnel used a system of iron rings patented by Joseph Dixon, and the longer straight part was brick-lined. The man sitting at the entrance has not been identified.

— Rockwood & Co., stereo card, photographed in March 1870. Brennan collection.

The drawing below shows the view from the tunnel toward the station. Here we see the car where it stood while it was not in operation. The the arched opening on the left leads to the Roots blower. Beyond the car and at a higher level is the waiting room, with lights from the sidewalk of Warren Street. Two people enter down a few steps from the double doors. The handle at the end of the car worked the brake, which grabbed a thin rail in the middle of the track. At the far end the conductor touched two wires together to signal to the engine room.

— Appleton's Journal of Literature, Science, and Art, June 25, 1870.

The company had no authority to carry passengers, but probably because there was only one station, it was not considered to be transportation. The 25-cent entrance fee was given to charity, netting nothing to the company. There was however a non-monetary benefit. Visitors were asked to sign a "memorial" to be brought to the state legislature, showing their support for a passenger railway like the one demonstrated. Dixon brought them to Albany the next month to back the bill under consideration.

Senator William M. Tweed introduced the bill— and on this point I contradict every historical account since 1872. But it was in all the newspapers. The very influential political boss was not opposed to Beach Pneumatic. It's not clear to me who wrote the bill, an amendment to the previous amendment, because while Tweed's career was built on obfuscation, this one carried on Beach's editorial method of changing parts of sentences. It openly allowed the company to carry passengers and use larger tubes to do so. But it did not describe where the tunnels would be built, referring casually to the original bill, which as I mentioned authorized tubes in any streets in New York and Brooklyn. The newspapers eventually called this out, and the uproar sent the matter to oblivion.

When a similar bill was introduced in 1871, it acknowledged the fault by naming specific routes. But it added a clause that nothing in the bill "shall be construed to limit or restrict any of the powers, rights and privileges heretofore granted", making nonsense of it. This time Senator Tweed was lukewarm. He had been given a financial interest in a rival project called the Viaduct Railway that had the backing of millionaire Alexander T. Stewart and most of his wealthy investor and banker friends, which was to be built with the proven technology of steam locomotives and masonry viaducts. Still, Tweed would not say anything to reporters against Beach Pneumatic. He just favored a plan that was much more likely to be built successfully, and tried to play it both ways until he could see what the future would bring. He would be happy to recommend his working-class constituents in the lower east side for the jobs either one created. The Viaduct bill passed. So did the Beach bill, but the governor vetoed it, because he said that it allowed excessive powers to the company.

What the future brought to Tweed was disaster. In July the New York Times began publishing articles based on papers provided by an informant that showed the corruption in Tweed's administration of his other public office as the head of the city's Department Public Works, a position in which he alone approved all city contracts. Since Tweed and associates had been publicly listed among the many incorporators and directors of the Viaduct company (most likely to assure "cooperation"), investors began to back out to avoid association with the now-scandalous "Tweed Ring". Anonymous engineers wrote letters to newspapers casting doubt on aspects of the Viaduct plan. It became "a dead cock in the pit". Some of the Times's smear compaign was not convincingly documented, but some of it was true. Tweed was eventually convicted of crimes in office.

Why do we think Tweed opposed Beach every step of the way? Because Beach said so, beginning in 1872. Simply denying history, Beach never again mentioned the bill of 1870. He called the bill of 1871 the first attempt and blamed Tweed for its not passing. It was as simple as that. Reporters had short memories. If Tweed was against it, then wouldn't honest people be for it? That was his pitch in his limited-edition illustrated promotional book The Broadway Underground Railway, and in his every further comment on the matter. But the Beach bill of 1872 was no better than those before, and the same governor vetoed it again.

The fourth version of the bill passed in 1873, by $75,000 spent on bribes, according to the Daily Graphic's reporter. Although it still provided the excessive powers, the bill now provided for oversight by independent commissioners, and a new governor signed it in March. But then nothing much happened. Beach reacted with astonishment, and then with mad plans where he imagined his Broadway Underground Railway continuing into two other underground proposals of the day, namely what became the Metro North tunnel from Grand Central and what became, after fits and starts, the uptown Hudson tunnels used by PATH. Beach was never known to have had financing other than himself. After the stock market collapsed in September, the Panic of 1873, hopes for Beach Pneumatic flickered out. The gradual progress of New York Elevated Railroad, a troubled venture starting to succeed, turned public attention away from underground railways for decades.

The Beach organization shut down the demonstration when the Act passed, and probably removed the Roots blower at that time. The lease of the basement ended in 1875 and the company moved out. While the Devlin clothing store continued on the ground floor, the basement suite was let to a rifle dealer called Homer Fisher, who also leased the Beach tunnel to allow his customers to shoot to targets at the far end. Fisher left just a few years later. By 1886 the basement was in use by Siegel's wine cellars, and in that year a reporter and friend explored the abandoned tunnel. They found both cars: the second open platform car that was added in late 1870, which they pushed back and forth, and the original closed car, which rested at the end near the shield.

In 1889 the Devlin store relocated to Union Square, and the building was taken by the Rogers, Peet clothing store, which used the basement as storage for their ground-floor shop. It was probably at this time that the tunnel was walled off from the basement. Back in 1875, Beach had secured permission from the Parks Department to "occasionally" open the grating in City Hall Park to go into the tunnel.

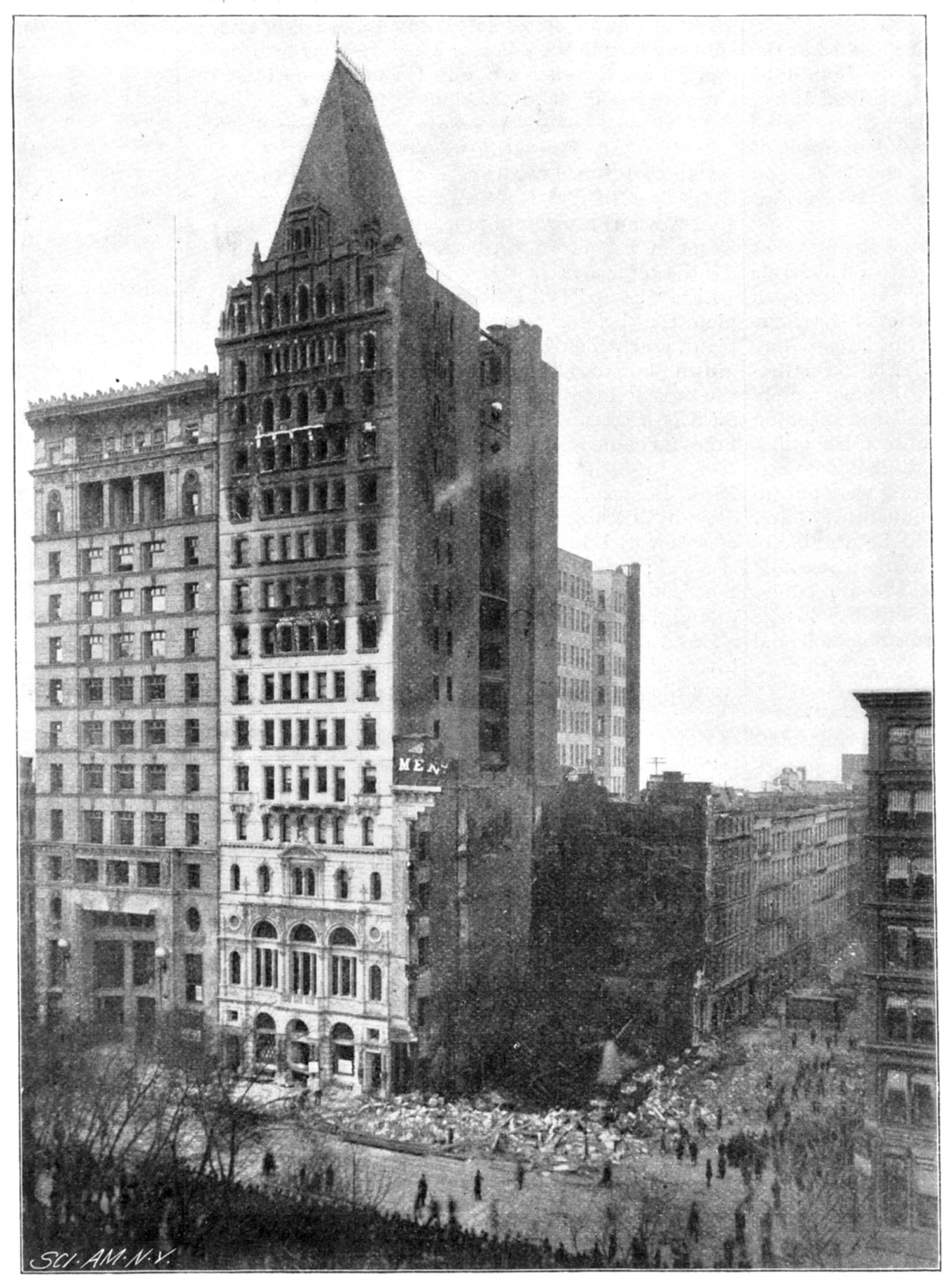

The building was totally destroyed by fire in December 1898, on a late Sunday night in a windstorm. All of the timber-framed interior collapsed, and the stone exterior walls fell as the mortar crumbled. If anything of the station had survived this long, which I doubt, it was lost forever. Construction of the replacement building, which is still there today as number 258 Broadway, included even new basement walls.

The photograph below shows the complete loss of the building. No trace of the waiting room could have survived this, even if Homer Fisher and Siegel's wine cellars had preserved some of the Beach Pneumatic interior. The other two buildings in the block, erected just a few years earlier, proved their "fireproof building" claim and are still in use today. Next to the ruin is the Home Life Building, with a little of the burned building still attached, including a sign for MEN'S furnishings above the cornice, and to the left of that the Postal Telegraph Building. Both suffered fire damage inside the offices on the upper floors, but the structure of the buildings was intact. Around the corner, the next building in Warren Street was as much a firetrap as the old Devlin structure, but was separated from it by literally a firewall.

— Scientific American, December 7, 1898.

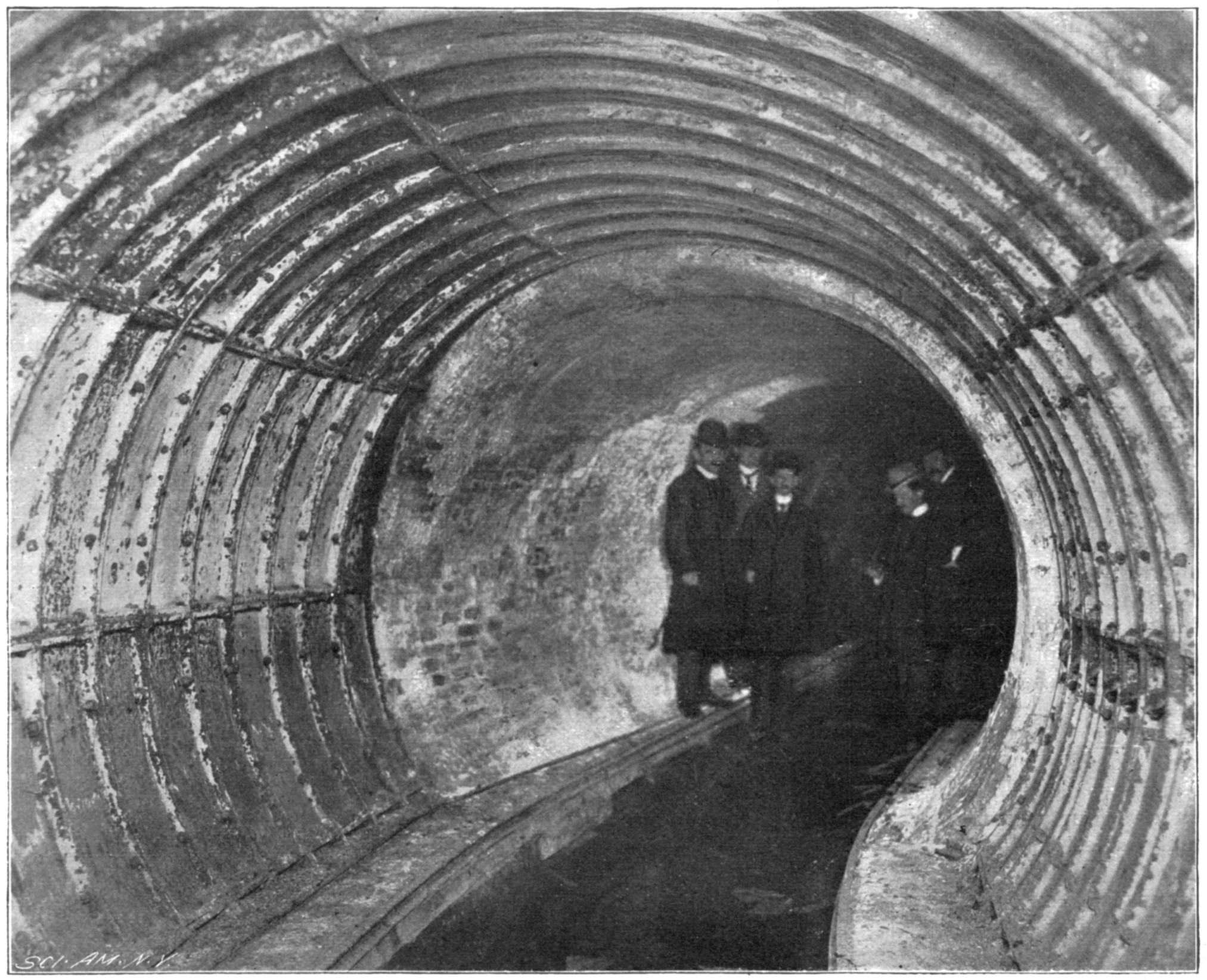

When the ruins were cleared, people from Scientific American were allowed access to the tunnel through the reopened tunnel portal in the basement wall. There was no fire damage inside, because the hole had been blocked up by a stone wall. The first picture below shows well-dressed men at the point where the iron-plated curve gives way to the brick-lined straight section. Both sections were painted white in 1870, and some of that remained.

— Scientific American, April 15, 1899.

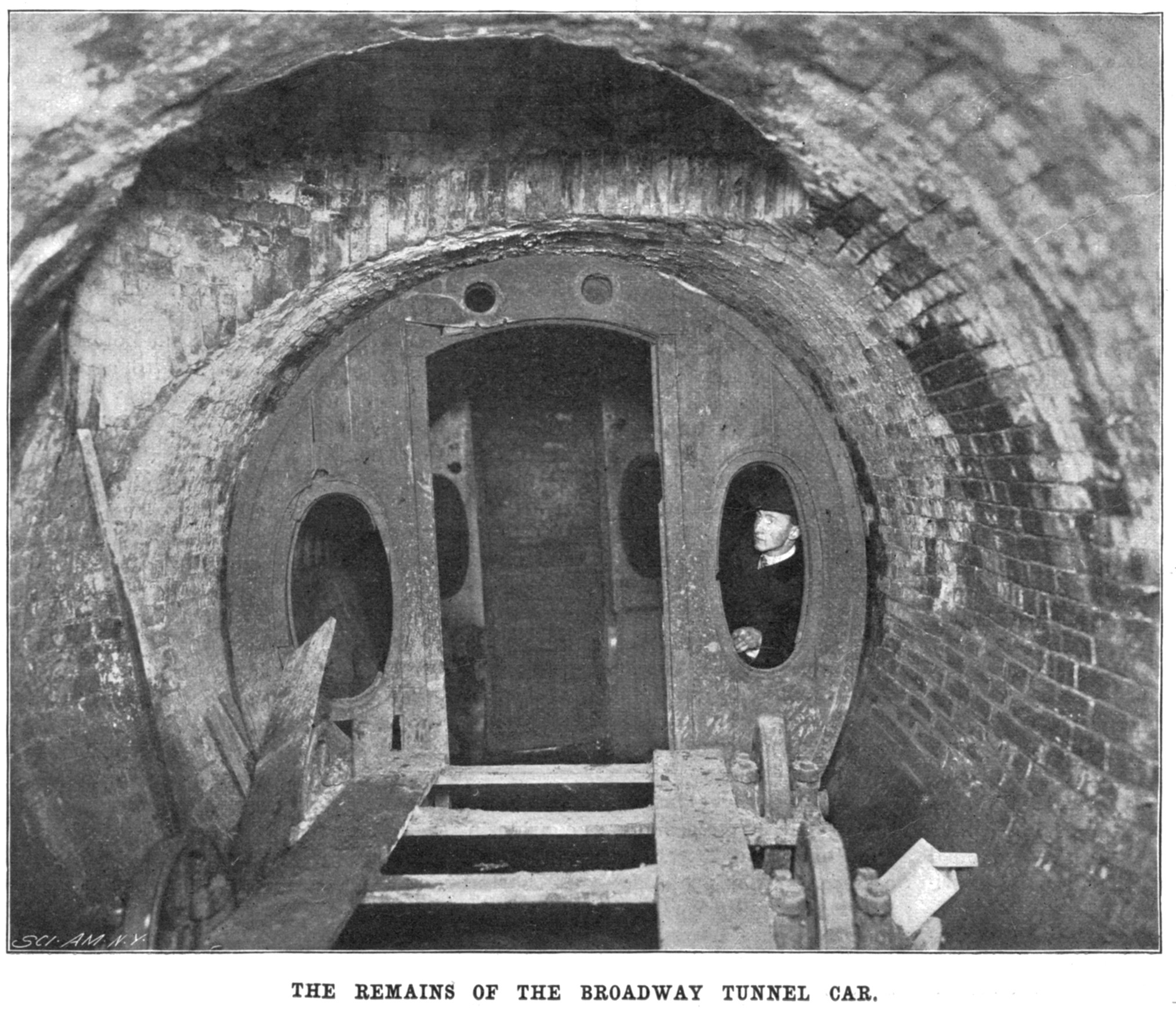

A second photograph shows the remains of the two cars and the large vent opening that went up to the grate in City Hall Park. Nearer the camera is the frame of the platform car installed in November 1870, which the reporters pushed gleefully by hand in 1886. Beyond is the original closed car, with a young man, said to be Beach's grandson Stanley Yale Beach, seen through the now unglazed window.

— Scientific American, April 15, 1899.

The tunnel was intentionally destroyed in 1912 during construction of the Broadway subway's City Hall station. Its existence was well known, and if I may again contradict pop history, it was not discovered by surprise. In fact the first thing done by the contractor and the Public Service Commission, after the contract was let, was to go down the grate in City Hall Park to take possession and figure out how to remove the tunnel. It was done by digging out around it and then cutting it apart.

The photograph below is from 1912, possibly July 25. The iron-plated curve is in the foreground. The slope of earth in the distance shows where the contractors broke into the brick-lined section from the west side.

— Public Service Commission for the First District, Report for the Year 1912, volume 1.

Beach's son Frederick was allowed to visit the construction site, and he arranged to have the historic tunnel shield carefully disassembled and sent to Cornell University's school of engineering for display. Sadly it disappeared long ago. Someone from the Public Service Commission had the end wall of the closed car taken up to their offices, and that too is now gone.

The entire tunnel was within the limits of the City Hall station, which is about 600 feet long and has two levels (one not used for passengers), making it much larger in every dimension, so there is no chance that part of the tunnel exists.