London and Croydon Railway

Forest Hill

In which Joe goes on and on about railway history, and then describes in depth the lack of any remains of the atmospheric railway at New Cross Gate and Forest Hill, with illustrations of what would be at the latter site if anything was left, and ends with a brief digression about the Thames Tunnel.

Explorations: Tuesday, 9 October 2018, and Tuesday, 18 June 2019

Journey: New Cross Gate to Forest Hill, London Overground

-

OFTEN CITED REFERENCES

- Howard Clayton, The Atmospheric Railways, the author, 1966.

- Charles Hadfield, Atmospheric Railways, David and Charles, 1967.

- John T. Howard Turner, The London, Brighton & South Coast Railway , volume 1, "Origins & Formation", B.T. Batsford, 1977.

- John T. Howard Turner, The London, Brighton & South Coast Railway , volume 2, "Establishment & Growth", B.T. Batsford, 1978.

The atmospheric installation on the London and Croydon Railway was the only one of the four that was not on a new section of railway. It was instead an additional track laid alongside two that were already in use for steam locomotives. But it was not an old established railway. There was no such thing. None of the railways involved had been in operation for more than ten years. I think a list of dates will be clearer than a series of paragraphs. (For this I and other information I am indebted to the fine research of John T. Howard Turner's books.)

1831: A new London Bridge opens.All that railway-building within ten years.

1833: Act for the London and Greenwich Railway

1835: Act for the London and Croydon Railway

1835: Agreement for L&CR to reach London Bridge on L&GR

1836, 8 Feb: L&GR open Spa Road to Deptford

1836: Act for L&CR to build its own London Bridge station

1836: Act for South Eastern Railway (from Croydon on L&CR)

1836, 1 Dec: L&GR open London Bridge to Deptford

1837: Amended act for SER (from Penge on L&CR)

1837: Act for London and Brighton Railway (from Norwood on L&CR)

1838, 24 Dec: L&GR completed, open London Bridge to Greenwich

1839, 5 Jun: L&CR completed, open L&GR to Croydon

1839: Amended act for SER (from Redhill on L&BR)

1840: Act for L&GR to widen viaduct

1840: Act for L&CR to enlarge its London Bridge station

1841, Jul 12: L&BR open to Haywards Heath

1841, 21 Sep: L&BR open to Brighton

1842, 10 May: L&GR widened viaduct open

1842, 26 May: SER open to Tonbridge

1842, 1 Dec: SER open to Ashford

The London and Greenwich was built on a brick arch viaduct in order to avoid level crossings in the built-up area and to stay above the soggy ground around Deptford. The viaduct was built for two tracks, with a London Bridge terminal of three tracks between two platforms. Construction included "boulevards" on both sides, at ground level, and while it might not have been planned, that property made possible the first few widenings of the viaduct.

The agreement to take the trains of the London and Croydon was made before the Greenwich even opened, and by the time it did open two further companies were planning to come in via the Croydon. The reason for this was that Parliament had a policy of limiting to as few places as possible the disruption of building new railways. It was not an unreasonable goal, but they did not give enough thought to operations, to how many trains per hour could be handled on a combined railway route. The Croydon company had the foresight to see trouble coming, and obtained powers to build another London Bridge terminal station next to the Greenwich one for their trains and the two other railways coming in on Croydon rails.

To recap: As built the South Eastern joined the Brighton at Redhill, the Brighton joined the Croydon at Norwood, and the Croydon joined the Greenwich at Corbett's Lane (not a station). Traffic from each source was however different in nature. In each direction the Greenwich had a train every fifteen minutes and the Croydon one per hour, and the Brighton and the South Eastern each had four per day. While the latter two had fewer train movements, being longer distance services their trains would need to dwell longer at the terminal to handle baggage and deal with the slower movement of the better classes.

The Croydon's station at London Bridge was built on the north side, because the Greenwich company had cleared land there for a larger union terminal that they were never able to afford, and so they were willing to sell it to the Croydon company. The location did not matter much until the widened viaduct was opened in 1842 on the site of the south boulevard. Dedicating the new pair of tracks to the Croydon made sense since the railway comes in from that side, but it meant that near the terminal trains of the Croydon and the Greenwich had to cross paths. It would have made sense for the companies to exchange terminals, but they could not negotiate terms to do so until 1845, after some corporate changes.

Building the viaduct had left the London and Greenwich Railway with unusually heavy debts to repay, which were financed to a substantial degree from tolls on the other companies that used it. Dissatisfaction with what they considered excessive charges led the South Eastern and Croydon companies together to obtain powers to build a new branch starting near Corbett's Lane junction and running to a terminal called Bricklayer's Arms. The location of the junction kept the South Eastern's fees to the Croydon intact but avoided paying anything to the Greenwich. On its opening on 1 May 1844 the new station hosted all of the South Eastern trains, and the Croydon offered an hourly service at about half the fare that was charged to London Bridge.

The location of Bricklayer's Arms was poor on almost any count, and yet the Croydon saw an increase in overall passenger traffic because of the lower fare. It took only a few months for the Greenwich to give in and reduce the tolls. Based on that the Croydon offered the same lower fare to either terminal, and as ridership increased further, most of it to London Bridge, the company's trains to Bricklayer's Arms were discontinued. Not long after that, the Greenwich agreed to a long term lease to the South Eastern starting on 1 January 1845. With this the SER also began to prefer London Bridge, finally ending services to Bricklayer's Arms after 1851. But Bricklayer's was a good site for a freight terminal, a role it played for more than a century further.

Now let's focus on the London and Croydon and the atmospheric railway.

Croydon was blessed with two means of transportation at the start of the century. The Surrey Iron Railway opened in 1803 from a dock on the Thames at Wandsworth. It was a plateway that followed more or less the River Wandle. The "rails" were L-shaped in cross section, so that ordinary carts could run on the horizontal surface, guided by the vertical surfaces that fit between their wheels. The company did not run any vehicles itself. Instead, like a turnpike company, they collected tolls from anyone who wanted to run their carts on it. Revenues were disappointing.

The Croydon and Rotherhithe Canal (its full name) opened in 1809 from a point not far from the Thames on the ambitiously named Grand Surrey Canal. A victim of canal mania, it was a slow and arduous method of transport that was not very successful. The number of locks was excessive, particularly the flight of 26 locks that were needed to climb up 150 feet to Forest Hill, and even after that a few more locks dotted its twisted path along the contours.

The London and Croydon Railway would do better than either of them. Its route, after it left the London and Greenwich viaduct, ran through the same territory as the Croydon canal, so the company purchased the canal in July 1836 and shut it down a few weeks later. For the most part the railway did not run on the same path as the canal, but it did cross the site of the canal many times. The climb from New Cross to Forest Hill was still an obstacle. The Croydon railway at first planned cuts and fills that would provide an ascent at a steep grade of 1¼ per cent, which would very likely require a "bank" locomotive to push trains up. Once use of the Croydon by the Brighton and the South Eastern was definitely agreed, the plan was changed to build more extensive earthworks and get the grade down to just one per cent. The deep cut south of New Cross is the legacy of this requirement. Trains began running from London Bridge to Croydon in June 1839.

The chronology up above shows that by May 1842, the Brighton and the South Eastern were running on Croydon metals, but their trains did not stop at the Croydon's stations. Within a year it was obvious that mixing stopping and through trains on the same track was not practical. The tenant railways often complained of delays from the stopping trains, while the Croydon wanted to add more of them and to extend their railway west to Epsom. The result was two Acts obtained in 1844: April, for the new line to Epsom, and August, for two more tracks north of the Brighton junction at Norwood.

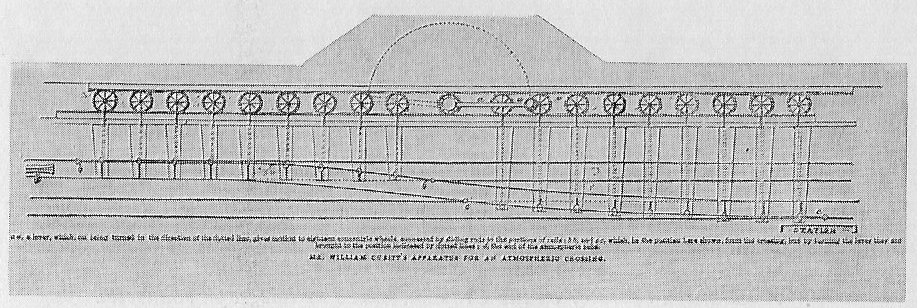

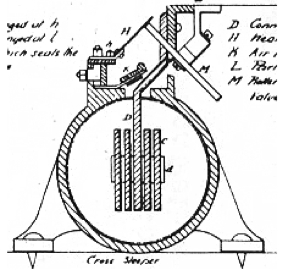

William Cubitt, the Croydon company's engineer, had not been impressed in 1840 by the Samuda demonstration atmospheric railway, but after the successful opening of the Dalkey line in August 1843, which spurred many plans for atmospheric railways in England, he turned around. He now proposed that the company build the Epsom extension as a single atmospheric track, to be run together with a new third track on the rest of the route to London Bridge. This would save money, he argued, over building two new tracks. Although the Board of Trade normally discouraged single track railways because of the risk of collision, one of the selling points of the atmospheric was that collision was impossible because two trains could not move in the same section of pipe. Another selling point was that atmospheric trains were not subject to slipping on grades, and that would take care of the climb to Forest Hill.

As a result of Cubitt's recommendation, at the London and Croydon shareholder's meeting in March 1844 the atmospheric system was approved, and the Act for the Epsom extension in August included authorization for atmospheric propulsion. By the two Acts, the company could add two tracks as far as the Brighton junction, add one and convert one from there to Croydon, and build two new out to Epsom. The company resolved to start with one new track. The Samuda brothers promised that with atmospheric operation, a passing track at Carshalton (Epsom branch) would allow one train per hour on otherwise single track, and another at Sydenham would allow two per hour. Reaching London Bridge was dependent on adding at least one track to the viaduct. The South Eastern, in control of the Greenwich from January 1845, obtained an Act to widen the viaduct on the north side by one track. The Greenwich trains were to shift over to use that and the original north side track, leaving the center track of the five available as the location for an atmospheric track.

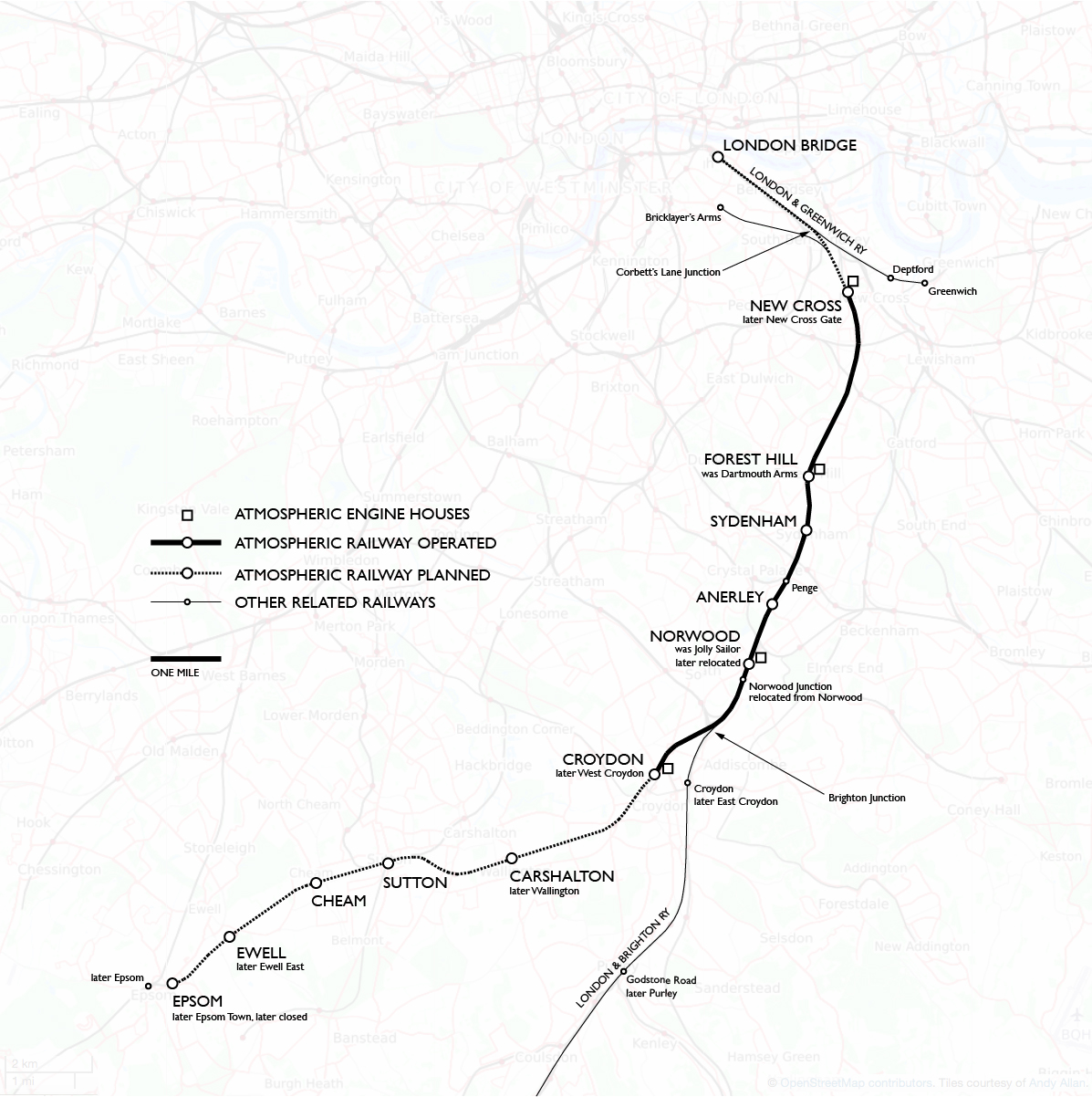

The built and unbuilt atmospheric railway is shown below. London Bridge to New Cross (New Cross Gate) is about 3 miles, to Croydon (West Croydon) 10½ miles, and to Epsom (original) 18½ miles.

Construction was planned in four stages:

1 Forest Hill to CroydonThe Epsom line was not yet built, nor was the track on the viaduct to London Bridge, so those had to be later stages. Stage 1 by itself would require only one change of power for the London–Croydon journey, so it made the most sense to start there.

2 New Cross to Forest Hill

3 London Bridge to New Cross

4 Croydon to Epsom

NEW CROSS

Since we will visit the site in order from north to south, we will start with stage 2, which included the "steep" one per cent grade. By the time stage 2 was ready there had already been a series of problems with the atmospheric system on stage 1 during the year it was running, since 19 January 1846. In December of that year the company decided to complete the Epsom extension as a locomotive railway. This made work on stage 2 practically useless, since it was hard to imagine changing motive power twice on a total journey of only 18 miles.

Nonetheless, Jacob d'Aguilar Samuda carried on. Test runs from New Cross were made on 14 January 1847 with some success. The Forest Hill engine house was equipped with a second pair of engines to pull trains up the grade, with an air gap between the stage 1 and 2 atmospheric pipes. For the time being atmospheric trains ran down to New Cross by gravity, and so the New Cross engine house was never used. Stage 2 was put in service on 27 February but ran for little more than two months, during which the system proved on too many occasions to be unable to get trains up the hill with normal loads, requiring a locomotive to stand by at New Cross at all hours of operation. All atmospheric operation ceased on 4 May 1847.

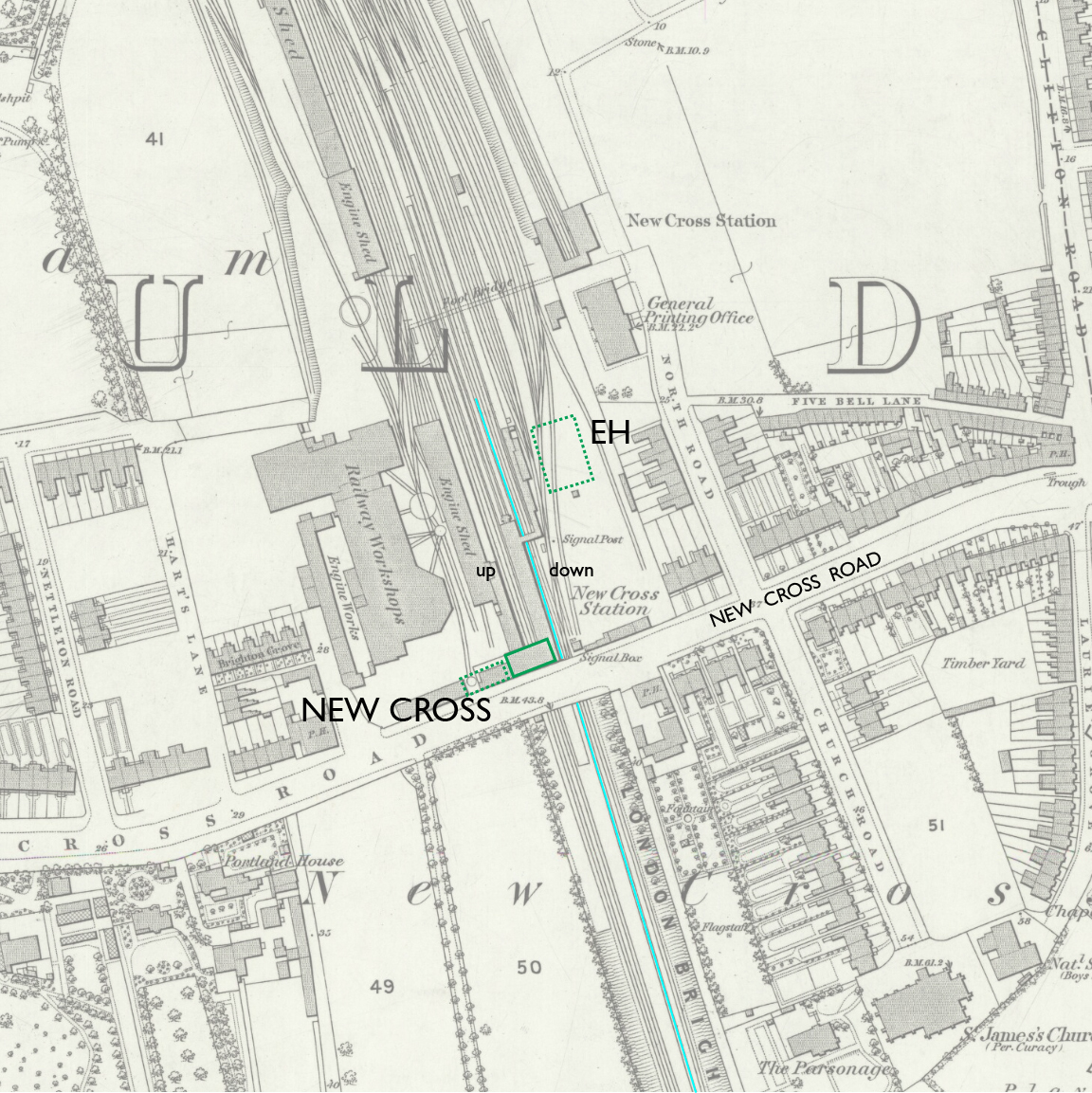

New Cross station, renamed New Cross Gate in 1923, was the farthest point north reached by atmospheric railway operation. Like the other London and Croydon stations it was built originally with a platform on each side of two tracks. Howard Turner wrote that the location was immediately north of the road bridge and that the platforms extended under the bridge.

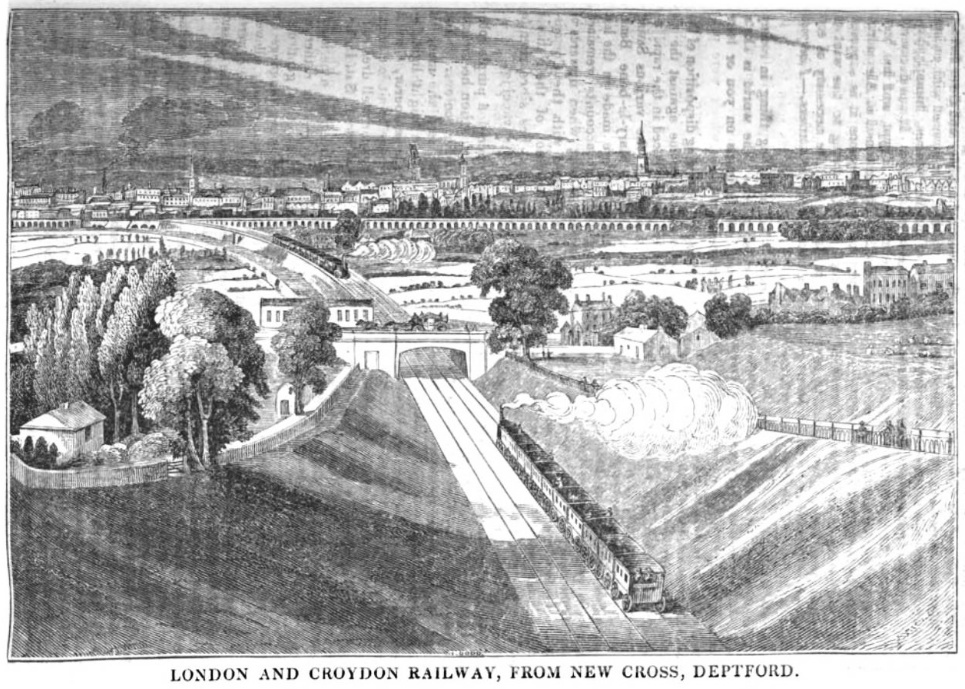

The image below was published on 9 March 1839, ten months before the Croydon opened, in the magazine Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. The deep cut south of the New Cross Road is obvious, and notice the fences protecting the top of both sides. On the bridge is a carriage moving right to left behind horses. I have to conclude that the white building to the left of the bridge was the station. Trains are shown running right-handed based on London and Greenwich practice in effect until April that year, and in the distance is that company's viaduct.

— Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction (via Google Books)

The present station house at New Cross Gate is over the tracks on the north side of the bridge carrying the New Cross Road. The bridge must have been rebuilt in 1845 when the third track for the atmospheric railway was added. Howard Turner reports that the down platform became an island, with the atmospheric track running along its other side to the east, and also that when the whole Croydon line was being four-tracked in 1854, the section around New Cross station already had four tracks. The bridge has two spans for two tracks each, so I think that the necessary rebuilding of the bridge for the atmospheric in 1845 allowed for the fourth track.

The station was closed from 1 October 1847 and replaced by another of the same name at Cold Blow Lane a quarter mile to the north. But the change was short-lived. The station moved back to the New Cross Road on 1 May 1849. The question is whether the present-day station is from that date or was built for the start of four-track operation in 1854. I can't tell. Either way it post-dates the atmospheric. (I wonder whether the Cold Blow Lane location was intended to let down trains gain some momentum before reaching the grade south of the New Cross Road.)

The exact location of the constructed but unused engine house is not given by any documents I have seen. It was almost certainly in the railway property just east of the station, some of which has still not been built upon. In his book Charles Hadfield quotes a description from the Railway Chronicle: "It is built of party-coloured bricks—deep red and yellow; a spiral line of dark bricks ornamentally winds round the pale brick shaft of the chimney. The engine-house has rather an Italian character."

— New Cross station, Ordnance Survey 25-inch, 1873. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 courtesy National Library of Scotland.

Annotations by Joseph Brennan: atmospheric track (light blue line) and approximate site of engine house (EH).

Changes at track level, constrained by the road bridge, have been minimal. The four tracks shown on the 1873 Ordnance Survey map are in the same location as those today, but there is now a fifth track on the east side used by down Overground trains. If you ride through on a train from London Bridge using the "down fast" track, you are on the alignment of the atmospheric.

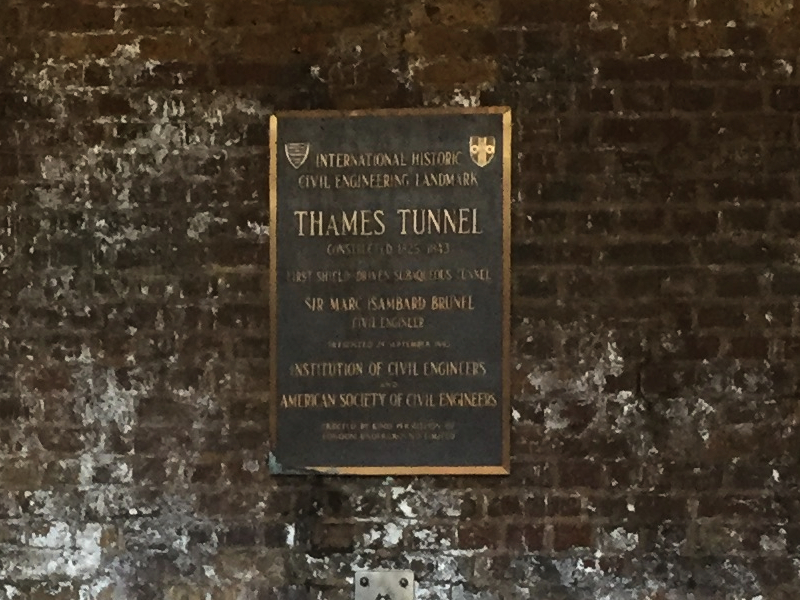

(The 1873 map shows further changes. The other New Cross Station above the General Printing Office was opened in 1869 for the East London Railway, which came down by way of the Thames Tunnel, the route used today by the London Overground, which now runs in the main station. The map also shows a track from the north ending between the original two tracks and the atmospheric, but Howard Turner's diagram (his volume 2) shows only a short stub track there, not a through track.)

FOREST HILL

Today the next stations from New Cross Gate are Brockley and Honor Oak Park, but they were not there until 1871 and 1886 respectively. One reason was sparse population, but that would apply to all of the territory except the established town of Croydon itself. The main reason was probably concern about starting down trains on the grade. Freight and other heavy trains were routinely assisted by bank engines. Howard Turner believes that the bank engines pushed from behind, so that they could drop off at the top at Forest Hill without any need to stop the train, and that they may have also led trains down the hill to add more braking power.

Forest Hill was an original London and Croydon station, under the name Dartmouth Arms, after a nearby public house. The name was changed to Forest Hill on 3 July 1845, before atmospheric operation began, so I will call it Forest Hill. Some writers continued using the old name for a few years longer, and of course modern writers enjoy using it.

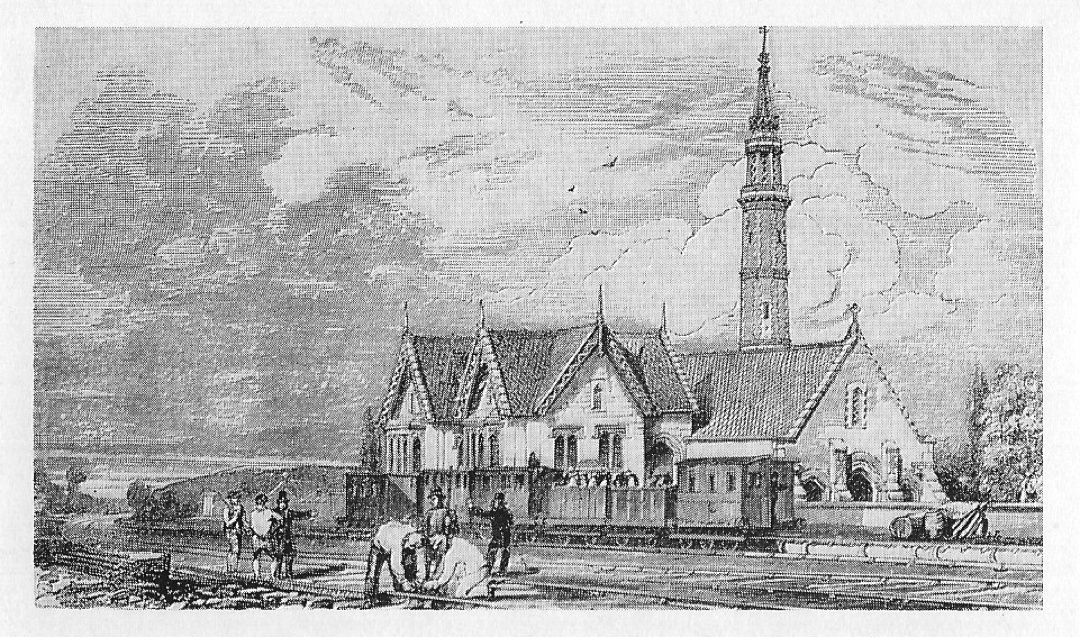

The original station house of 1839 was the one in use during the the atmospheric period. It was on the west or up side, nomenclature that is a little confusing here because "up" trains on this line are the ones going down hill. When it opened there was a level crossing with London Road that was eliminated during the winter of 1843 to 1844 by diverting road traffic to the north and under the railway. To preserve the old public right of way, a foot tunnel under the railway was also provided. The company's decision to use atmospheric power came just after the crossing was closed, but Cubitt's interest preceded that, and so we don't know to what extent it might have influenced closing the crossing.

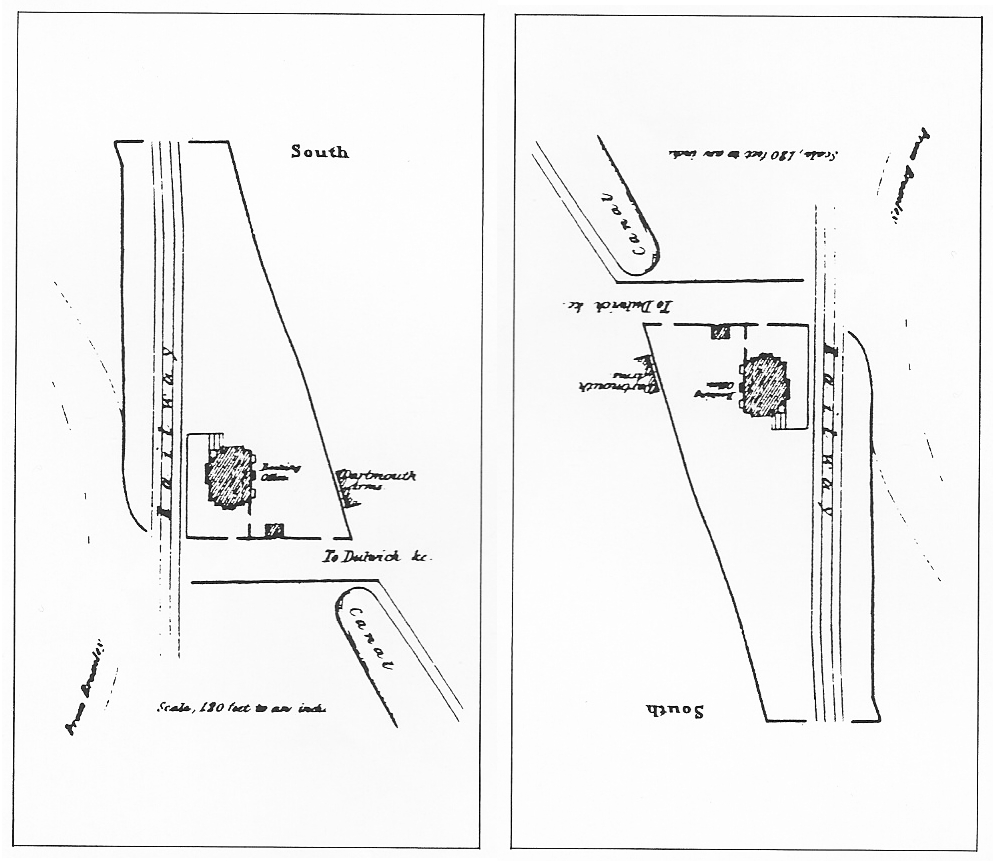

Thanks to an excellent article by John Minnie in British Railway Journal number 71, "Forest Hill", we have a description of the 1839 station from the now rare book The Croydon Railway and Its Adjacent Scenery by W. E. Trotter, published in 1839. It was "a neat structure of brick with dressings of stone, surrounded by a substantial wall with large folding gates at each extremity." A sketch map from the book is below. Since it has south at the top, I show it in the original form so that the words are legible, and also rotated 180 degrees.

— Forest Hill station, from The Croydon Railway and Its Adjacent Scenery, 1839, via Minnie, British Railway Journal

Notice that part of the canal was still there, as it was in some other places. Here it was used as a source of water for the atmospheric engine house, and in later days it was called an ornamental feature, even though in 1854 it was blamed for an outbreak of cholera. The canal formerly continued under a drawbridge and then between the Dartmouth Arms and the station site. A property line still follows that route.

The atmospheric track was added on the east side all the way to Norwood, and Howard Turner writes that at Forest Hill once again it made the down side platform into an island. Here a new side platform for the atmospheric track was also installed next to the engine house, as seen in a contemporary illustration. For thirteen months this was the place where locomotives and piston cars exchanged roles while passengers waited in the cars.

I want to describe how the power change was done, but I have to admit defeat, if my sources are correct. The locomotive could not switch to another track once it was over the atmospheric pipe, and the piston carriage could not ride over a switch at all unless the piston was lifted. Gravity does not explain the movements unless the track was down hill in both directions. Writers have speculated about horses, cable winch from the engine house, and even a gang of men. If any of this interesting activity had gone on, you'd think observers would have commented on it, but they let it pass.

We have a report of the "special exhibition" run of 20 October 1845 from the Illustrated London News issue of 25 October. The train of nine or ten cars stood at Forest Hill for five and a half minutes, and then moved by means not stated for a minute and a quarter before it began to move by atmospheric power.

At nine minutes before two, the train, drawn by a locomotive, left the London station, arriving at the Dartmouth Arms, the point at which the atmospheric line commences, in eleven minutes. At seven and a half past two, the train again left its point of rest, and at eight minutes and three quarters past two, the piston got into the pipe, and proceeded at a rapid rate. Within a minute, a speed of 12 miles an hour was attained ; in the second minute, 18 miles an hour ; in the third minute, 25 miles ; in the fourth minute, 34 miles ; in the fifth, 40 miles ; and in the sixth minute, it reached its maximum speed, which was about 52 miles an hour, at which it continued till it slackened speed, on approaching the Croydon terminus.Details of the speed, and also of the atmospheric pressure that I am not quoting, could only have come from someone in the piston carriage. This is not purely a reporter's notes. The account in The Times of 23 October reads even more like a press release. We find that the pipes are the usual 15 inches in diameter and 10 feet in length, "emptied of air by an engine at the nearest station in advance of the train which is to travel [sic]." In contrast to the documented time, this article says, as if the reporter was not there, that "the exchange of the one leader for the other will scarcely occupy a minute." This part is of interest: "All the passing, and on single lines the meeting, must take place at the stations by means of sidings, which, we may observe, are to be about 1,000 feet long." No such thing was implemented on the Croydon line, unless the change at Forest Hill was done using some of this magic.

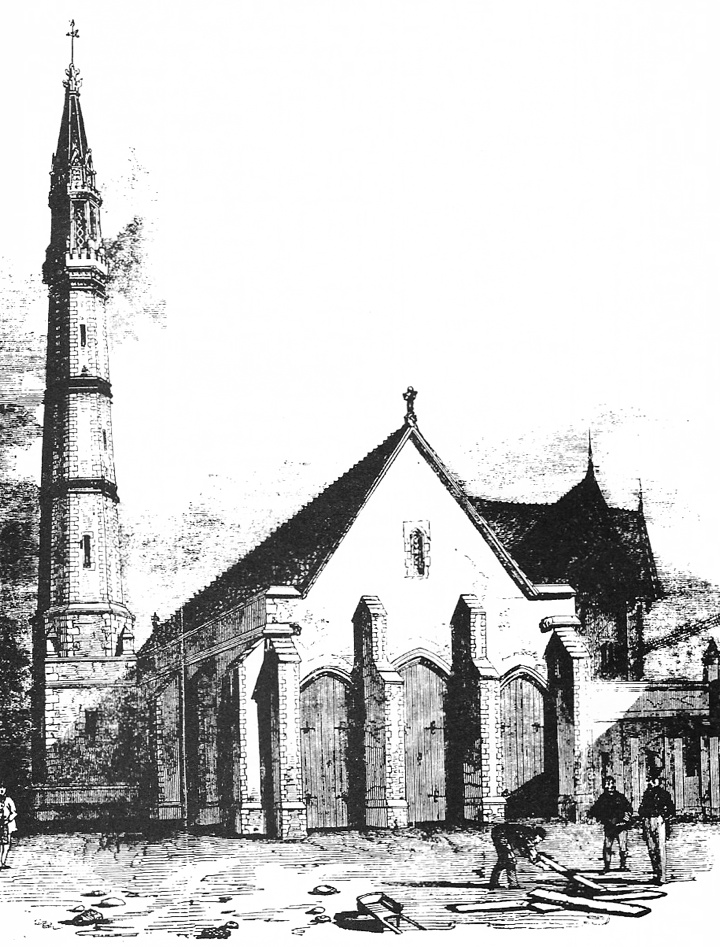

We are lucky enough to have two drawings of the engine house from different angles.

— Forest Hill engine house, original source unknown, via Charles Hadfield.

The view from the track side has appeared in a few publications, and this copy, despite some dot screen damage, is the clearest I have found. The engine house was on the down side, so we are looking at a train that has been attached to a piston carriage and is therefore about to leave. The 1839 station house is south of here, but the train evidently has stopped at a new platform, partly seen on the right with a few indistinct objects on it. By the usual convention of the time the third class carriages have no roof, and for the next part of this rare journey those passengers need not worry about cinders from a locomotive. It's too bad that we don't see where the locomotive has gone. Most of the fine architectural work protects not the passengers but boilers, steam engines, and air pumps. The men in the foreground are ignoring the whole scene, and I wonder what they are doing.

— Forest Hill engine house, original source unknown, via Howard Clayton.

Now we around the back of the engine house, with a fine view of the stalk, as the chimney was called. It exhausted not only the smoke and steam of the engines but the air pumped from the atmospheric pipe. More workers are at mysterious tasks with a wheelbarrow and what seem to be wooden boards.

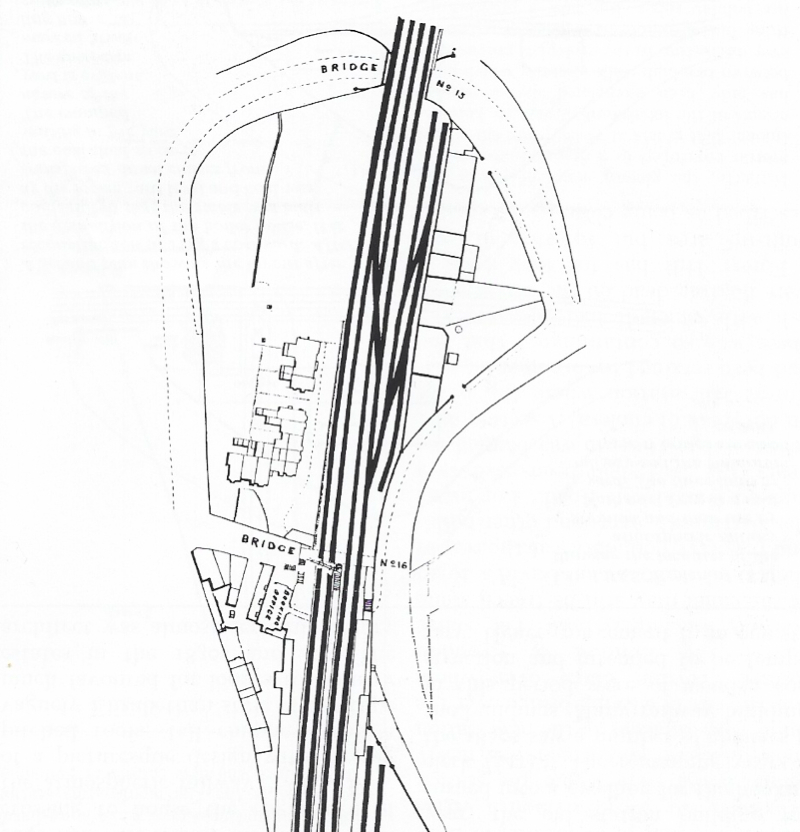

Minnie's article includes also a plan dated 1852 for the location of tracks after the widening that was completed in 1854. The fourth track was added here on the east side. There is no trace of the engine house, which had been in the triangular space to the east, where we see here two planned sidings and some thin lines marking the premises of a coal merchant. The 1839 station house is still in place, marked "booking office", just south of Bridge No. 16 (the underpass that replaced the level crossing). This plan is the most accurate plot of the location of the first station and confirms that the second station was built on the same site.

— Forest Hill planned improvements, via Minnie,

British Railway Journal.

The original down platform can be seen between the original down track and the atmospheric track, with a stairway up to it from the underpass. It was built as shown, a very narrow island between what became the center tracks, reached by stairs from the underpass. Only a few feet wide, it was the subject of many complaints. Danger was mitigated by not allowing the public on the platform except when a train was stopped next to it, and in another rebuilding in 1884 it was widened to six feet.

Let's jump ahead fifty years to see what was left.

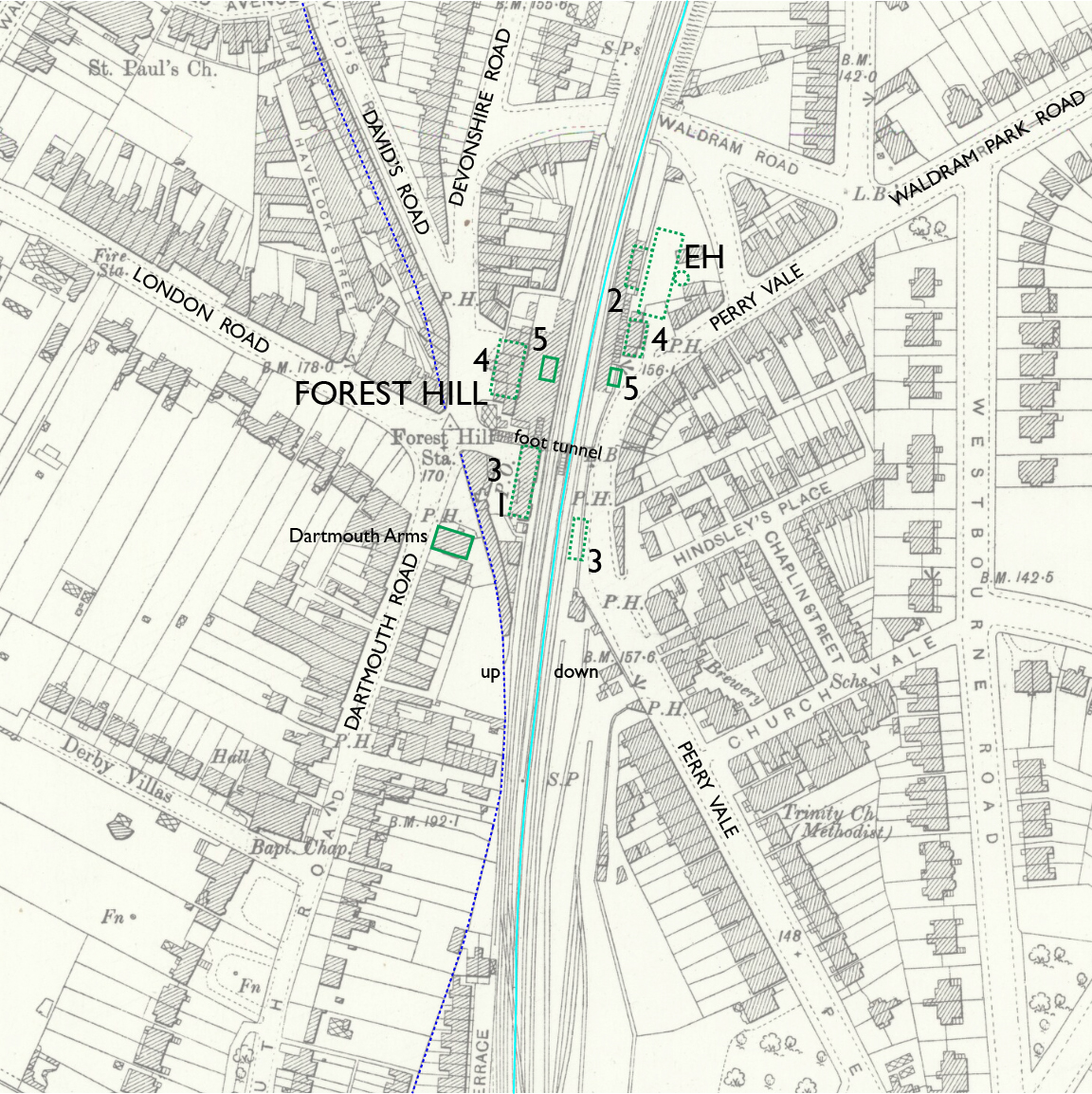

— Forest Hill station, Ordnance Survey 25-inch, 1897. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 courtesy National Library of Scotland.

Annotations by Joseph Brennan: atmospheric track (light blue line), site of engine house (EH), center line of canal (dashed dark blue line), site of stations of 1839 (1), 1846 atmospheric (2), 1854 and 1860 (3), and 1883-84 (4), and station of 1972 (5).

The drawing of the engine house shows a platform along the atmospheric track at which trains stopped. Whether it had station facilities for passengers is not known, but if it did they were lost when the engine house was demolished. I show it as station 2 on the map.

The second station of 1854 was "Italianate in style" (Minnie) and "echoes on a smaller scale many of the architectural features of the three-story frontage block at London Bridge built in 1853-54." By the time of the map above, the building was under lease to the Post Office, and it survived until 1944. A station house was installed on the down side for the first time in 1860. Both are marked 3 in the map.

The larger third station was completed in 1883 on the up side and the next year on the down side. Marked 4 on the map, both were located farther north. The up side building was set back to allow for a possible fifth track in the station. The down side was relocated in connection with widening of the street called Perry Vale. During the construction the underpass was rebuilt to the form seen on the map. What had once been a ramp running down from the west side that some critics compared to a drain was now a level passage down 27 steps from the street on the west side. Letters to the editor then complained about the steps instead.

As if widening to four tracks and two replacements of the station buildings were not enough to obliterate all trace of the atmospheric railway, on 23 June 1944 a German missile exploded on the up side, destroying the second building 3 and a good part of the third 4. The former was razed, and what was left of the latter was patched up under wartime economies and left that way.

In 1972 British Rail removed everything, including the almost unharmed down side, in favor of smaller and much less distinguished buildings in a then-contemporary style. There are still staffed entrances on both sides, and an overhead footbridge connecting them. The underpass is not considered part of the station and has no access to platforms. In the 2008 Heritage Audit of the London Overground the committee Design for London wrote, "This station is now of little historic or architectural interest and merits redevelopment" by which they meant, any plan for demolition and replacement is welcome.

Below, two pictures of the station on a rainy day in October, looking south on the footbridge and at the bottom of the steps from it. The "wide" space between the center tracks is the site of the island platform that was closed sometime in the 1960s and removed before 1972. In the view from the bridge, on the right, the peaked roof is the top of the Dartmouth Arms. In the lower picture the Southern Railway train is running on the down main track, where the atmospheric was.

The view in the area of the engine house is obstructed now by several commercial buildings. The small non-railway building on the left is next to the east side station house. The brick wall shows evidence of various earlier formations but the stairway is definitely the same one built for the 1884 station house. We are looking through the site of the south end of the engine house.

Lastly, here is the Dartmouth Arms. This building dates from 1867, so it is not the the exact premises wherein passengers might steady their nerves before boarding an atmospheric train. The earlier establishment included this property and also accommodations for man and horse to the south, where there is now a row of shops. Dartmouth Road runs in front. I do not know which first took the name Dartmouth or what connection there may be to the port town on the River Dart in Devon, but I observe also the name of Devonshire Road north of the station.