South Devon Railway

Exeter St Thomas

In which Joe is still in Exeter, and finds himself admiring two sets of stone arches.

Explorations: 26 June 2018, 28 June 2019.

Journey: Paddington to Exeter St Davids, St Davids to St Thomas.

-

OFTEN CITED REFERENCES

- Paul Garnsworthy, editor, Brunel's Atmospheric Railway, The Broad Gauge Society, 2013.

- Peter Kay, Exeter–Newton Abbot: a Railway History, Platform 5, 1991, and excerpts in Garnsworthy.

- Peter Kay, "The First St Thomas", British Railway Journal No. 45, 1993.

- Howard Clayton, The Atmospheric Railways, the author, 1966.

- Charles Hadfield, Atmospheric Railways, David and Charles, 1967.

- G.A. Sekon, A History of the Great Western Railway, Digby, Long, 1895.

Exeter St Davids was important to the South Devon Railway mainly for the exchange of passengers and freight with the Bristol and Exeter Railway. From there, the SDR crossed the Exe and skirted the southern edge of Exeter in the Parish of St Thomas. It's flat ground, but because of the several cross streets the railway runs on a stone viaduct through the built-up area, with an embankment of almost undetectable grade on each side. In its 501 yards the viaduct is carried on 60 arches: 13 of a standard 25 feet between the center of each pier, a wider one for Cowick Street, 45 more of the standard, and a wider one for Alphington Road. Some houses that Brunel dismissively called "sheds and hovels" had to be removed, but the company's route avoided any disruption to the city center.

Cowick Street is the closest place on the line to the old Exe Bridge and the center of Exeter, so it made sense to put a station there. It is hard to believe that the railway bosses did not realize that because St Thomas is more convenient to the city, it would attract most of the passengers who were going to or from Exeter itself.

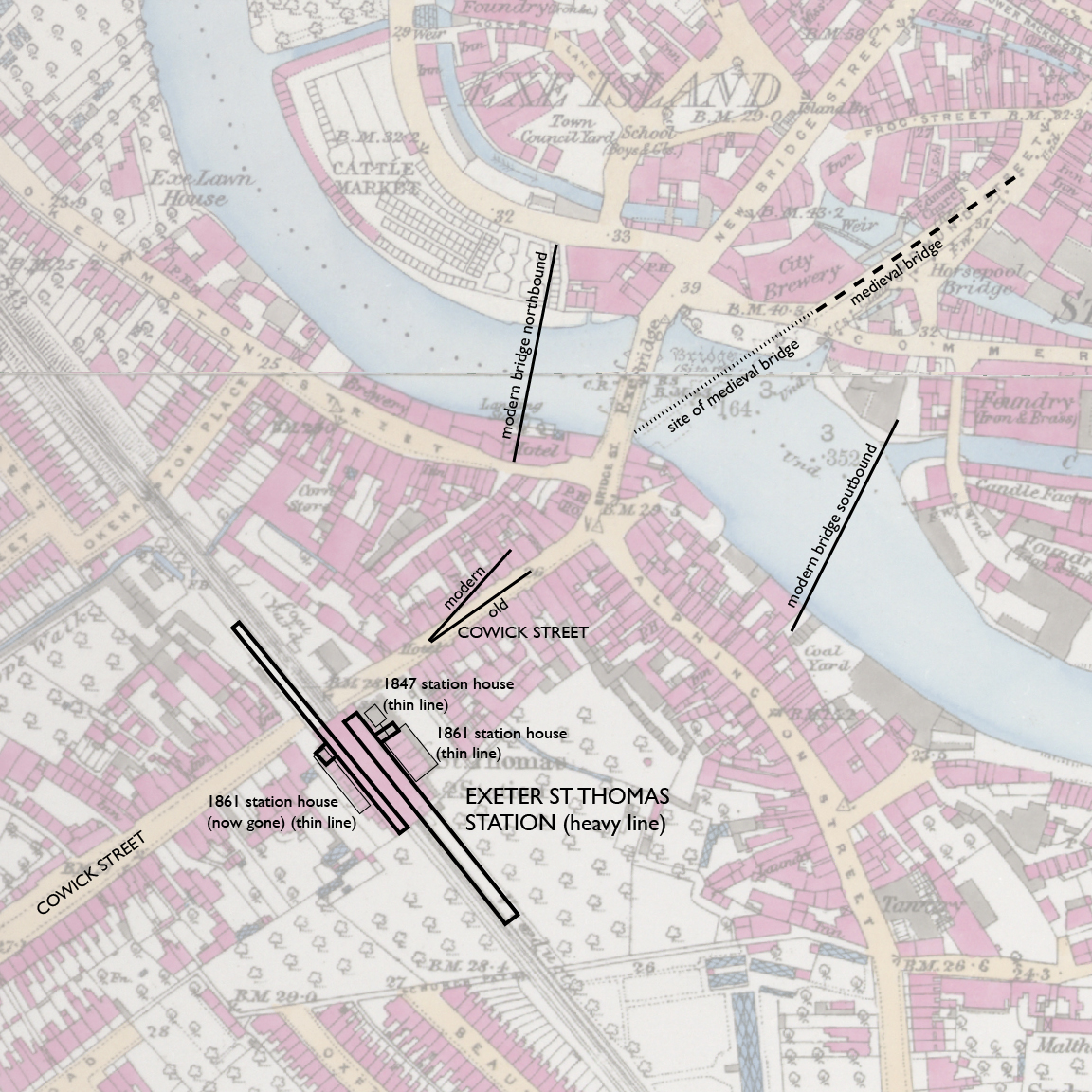

— Exeter St Thomas station, Ordnance Survey 25-inch, 1890. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 courtesy National Library of Scotland.

Annotations by Joseph Brennan.

Pedestrian access from Exeter to the station is less easy than it once was, because of extensive roadworks related to the two modern bridges. There is at least a network of subways to avoid crossing most of the speeding traffic at grade, but the ramps necessarily add distance to what was once a simple walk. In the map above I have indicated the center lines of the modern bridges and of the widened Cowick Street. The station platforms extend in different directions, as shown.

St Thomas was the only station on the atmospheric railway that was not at an engine house. It meant that there was no break in the tube, so the train crew had to stop by screwing down the brakes against the pull of the vacuum. All of the stations had problems with trains overshooting the platform, but things were particularly chronic at St Thomas. Atmospheric trains cannot back up. Upon one occasion on 29 January 1848 the down train stopped more than half a mile past St Thomas, and to appease angry passengers on the platform, the last car of the train was uncoupled and pushed back by hand to the station, and it was then pushed forward to the waiting train after the passengers crowded in.Peter Kay wrote an important article, "The First St Thomas", for British Railway Journal No. 45, 1993, from which I will take some information, including the story just told. You should see the article for more detail and some rare illustrations.

The SDR did not open until Saturday, 30 May 1846, but St Thomas was complete to specifications by March 1845. The viaduct was built for a single broad-gauge track, and for a station platform the first seven arches south of Cowick Street were made wider across by five feet on the city side. There was no covering over the platform or over the steps from street level at the north end, and the booking office was built into the first arch. See Peter Kay's article for a rare technical drawing showing the city side of the station and nearby arches.

This poor excuse for a station was overwhelmed from Day 1, the start of a holiday weekend. On Monday St Thomas was even busier. Within a few weeks the SDR asked Brunel to "effect more extended arrangements", but he replied that a small booking office and no roof was the usual Great Western Railway provision at "small stations", as if he still did not understand that this one served the largest population on the opened portion of the SDR. A second plea in August got results.

The second state of St Thomas station was completed around April 1847. There was now a wooden station house at ground level, a wooden roof over the stairway, a wooden trainshed covering part of the station, and a longer platform, extended to the south. St Thomas became the main station for people travelling between Exeter and points west.

William Dawson drew closer views of St Thomas than any other station on the line, perhaps because he lived in Exeter. Both views are from impossible points of view suspended in air next to the viaduct. Once again I acknowledge Brunel's Atmospheric Railway.

— William Dawson, "From the Station in St Thomas to the Alphington Meadows", detail, via Brunel's Atmospheric Railway.

The view above looks south, away from St Davids. For no reason I know, the trainshed had an arched opening on this side and a simple horizontal on the other. Dawson had problems with perspective. On the left, Cowick Street comes in from the city, but it crossed under much closer to the station than it appears to do here. The wooden station house of 1847 at ground level looks as if it is only a few steps lower but the platform was about 16 feet higher.

— William Dawson, "From the Alphington Meadows to the Station in St Thomas", detail, via Brunel's Atmospheric Railway.

The view above looks toward St Davids. The platform extension with a wooden railing contrasts with the stone parapet of the original. Dawson somehow does not show the arches below, giving the appearance of a stone-walled embankment rather than a viaduct. His profile drawing (see Brunel's Atmospheric Railway) does of course show the arches.

The third state of St Thomas was the result of double tracking. The SDR obtained an Act to do so in 1860 (I wonder why, since the original Act specified double track). Work from St Davids to Starcross was completed by September 1861. The viaduct was widened on the side away from the city. As Peter Kay takes pains to point out, the present-day station building dates from this period, not earlier as has sometimes been stated. Obviously a new platform was added on the up side, and an overall trainshed roof. The new up platform extended across Cowick Street and a half block beyond, while the old platform, now exclusively the down side, was extended a little farther south to match the length.

— "St Thomas's Station, Exeter, 1966", via Howard Clayton.

The Reshaping of British Railways, 1963, better known as the Beeching Report, recommended the closing of over two thousand stations, and this was to be one of them. St Thomas was a survivor despite the limited schedules it was being given in the 1960s. The third state is seen above in 1966 in its last years. Peter Kay's article has a photograph of 1921 from a similar point of view, the station differing by curved woodwork at the upper corners of the main opening, and by so much soot on the glass above the opening that it looks like a solid wall. An interior photograph in the same article shows that both sides had the customary amenties at track level: toilets, a newsstand, and separate waiting rooms for first and other classes.

The fourth sad state of St Thomas dates from 1970, when the trainshed was removed, the up side station house was demolished, and the down side station house was given up to non-railway use. Photos online show a ghastly appearance of neglect as late as 1975. It looks much better today, which we might call the fifth state, but it is still unstaffed and it has only very small shelters on the platforms.

Let's look around the station today.

— Exeter St Thomas, looking north on the down side.

Above, in 2019 a crowd wait for a train to St Davids, which will reverse there and continue to Exeter Central and the Exmouth branch. In the lower photograph, a peaked roof in the center distance matches the one in the 1966 picture. The 1861 station house looks reasonably good from here. The middle of the platform has been treated to a hump to bring it closer to train floor level. On the other side it looks as if the entire platform was raised after the trainshed and up station house were removed. Far left: non-stopping trains are allowed 75 mph past the platform.

— Exeter St Thomas, stairs from the down platform.

From the steps of the down platform we get a closer look at the 1861 station house and a certain level of filth and a healthy growth of moss. The pigeon spikes do prevent at least one further problem.

At the bottom we will turn right and go examine the arches.

Six arches from Cowick Street were covered up on this side when the station house was built in 1860-61. The seventh arch was closed up, but half of it is visible. This was also the end of the original short platform, still marked by the slightly lower wall for the 1847 extension, which runs for two more arches (50 feet). The outer surface of the viaduct continues to the same width, meaning that Brunel widened it by the same five feet as he did for the original work. The enlargement below will highight the change in the masonry at this point.

— Exeter St Thomas, arches under the viaduct.

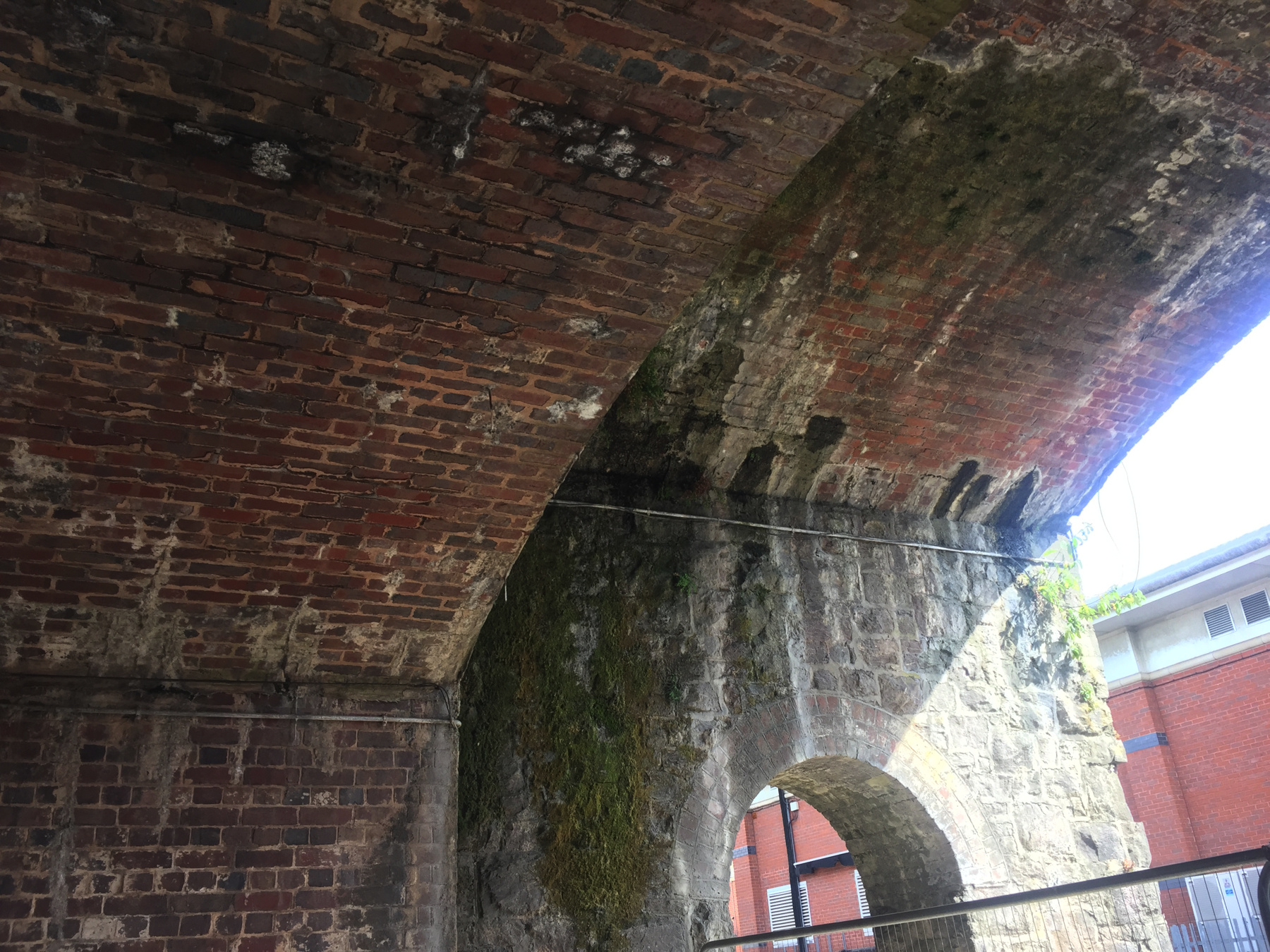

From the picture below it is clear that we have two kinds of arches to explain, but there are three phases of building: the original work completed in 1845, the platform extension of 1847, and the double track of 1861. On a web page I cannot now find I saw this described as Brunel's arches on the city side and the other lower arches as those for the second track. But I don't think so.

It did not occur to me when I was there to pace off the width of the two parts, but from counting bricks in the photographs I estimate that the higher city side is not nearly wide enough for a 7-foot-gauge track, a 5-foot-wide platform, and parapet walls. Rather, it seems wide enough for only the latter two features. Let's add two more facts. One, the taller arches supported on smaller arches appear only here under the platform extension. Two, a rare drawing from the 1840s reproduced in Peter Kay's article shows exactly what we see here: higher and therefore thinner arches under both the original 1845 platform and its extension.

— Exeter St Thomas, arches under the viaduct.

My conclusion is that the lower arches represent the first and third phases side by side, with thicker arches to carry the weight of trains overhead. The up platform does not come down this far, so the lower and stronger side here needs to be only wide enough for two "narrow gauge" tracks (as Brunel would say) and a parapet, and I think it is.

Above, the end of the 1847 platform is marked by a "buttress" with a much wider foot. You may be able to make out some varying treatment at the tops of the arches in the distance. The second one we can see is walled up. It reminds me that quite a few years have passed since all this was built. Quite a few. It stands to reason that many repairs and changes have been made in the meantime.

— Exeter St Thomas, arches under the viaduct.

Here we are inside the last tall arch, facing toward the buttress. This is the best exposure I got of the interior. Up on the right is what was the outer surface of Brunel's original arches before the platform extension.

— Exeter St Thomas, Cowick Street arch.

This is the city side of the wider arch at Cowick Street. The 1861 widening on the far side matches exactly the height of the original arch, but there are slight differences in the stone and brick work halfway through.

— Exeter St Thomas, Cowick Street arch.

This view is from the modern stairway on the up side, looking toward St Davids. In the distance is the end of the platform, not the end of the railway as it may appear! Here on the "new" side the South Devon used two types of stone for decorative effect, one of them the local red. The next arch over there is open for pedestrians to supplement the narrow walks in the main arch. Why it has a flat drop ceiling, I do not know. I wonder what's inside there above it. And what is behind the three little grills, lower right? I am full of questions. Notice the sign in the foreground for the very specialized rental agency "The Arch Co."